Burngreave

| Burngreave | |

Burngreave |

|

| Population | 27,481 (Ward. 2011) |

|---|---|

| OS grid reference | SK363884 |

| Metropolitan borough | City of Sheffield |

| Metropolitan county | South Yorkshire |

| Region | Yorkshire and the Humber |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | SHEFFIELD |

| Postcode district | S3 |

| Dialling code | 0114 |

| Police | South Yorkshire |

| Fire | South Yorkshire |

| Ambulance | Yorkshire |

| EU Parliament | Yorkshire and the Humber |

| UK Parliament | Sheffield, Brightside and Hillsborough |

Coordinates: 53°23′28″N 1°27′11″W / 53.391°N 1.453°W

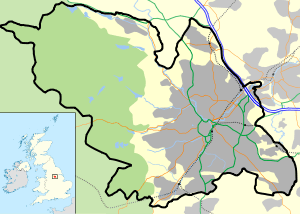

Burngreave is an inner city district of Sheffield, South Yorkshire, England lying north of the city centre. The population of the ward taken at the 2011 census was 27,481.[1] It started to develop in the second half of the 19th century. Prior to this, this area was mostly covered by Burnt Greave wood. Most of the area of the wood is now covered by Burngreave Cemetery. Grimesthorpe Lane, which runs through Burngreave, is a very old road that follows the course of the Roman Rig, a man-made defensive ridge—probably built by the Celtic Brigantes tribe—that used to run from near the Wicker to Mexborough.

History

Celtic tribes, Romans and Vikings

Although there is not much physical evidence of early settlement in Burngreave, we do know that an Iron Age fort was discovered in Roe Woods. The people who built this may have been from a Celtic tribe, the Brigantes, who were based near Huddersfield. In the early 20th century you could still see the circular banks of the fort they had built. In 1922, however, it was destroyed to build a sports ground (now owned by Sheffield United FC). It has been suggested that this fort may have been linked to the nearby hill fort at Wincobank, possibly as outer defences against other tribes.

The Romans first arrived in the north of England around 54AD. They met fierce resistance from northern tribes, particularly the Brigantes. So they built forts, such as the one at Templeborough, near Rotherham. There is very little evidence of the Roman presence in Burngreave. A hoard of 35 Roman coins was found on Scott Road, right in the middle of Burngreave. They date between 50 and 200AD, suggesting that Romans were at least passing through the area during that time. There is also the remains of a massive earthwork, known as the Roman Rig, which ran through the Lower Don Valley and along what is now Grimesthorpe Road. However we don't know how old it is or who built it. It may have been built to keep the Romans out.

Around the mid 9th century the north of England fell under Danish control. Several local place names suggest Viking settlement in the area. Osgathorpe (an old Danish name) means the farm belonging to Osga and Grimesthorpe means Grims outlying farm. From this we can imagine that the area was occupied by a farming community at a time when Sheffield was still a small, insignificant place. The name of Roe Wood may possibly be derived from the old Norse word ra meaning rowan tree.

Middle Ages onward

In the 12th century, a local lord of the manor founded a hospital in the area, called St Leonards. Although there is no trace of it remaining, the name has been passed on to streets in the vicinity, called Spital Hill and Spital Lane (as in hospital).

In the 13th century, a Norman family called De Mounteney were prominent in the area and owned land around Shirecliffe and Grimesthorpe.

In the 15th century and 16th century, Burngreave was an area of open countryside with scattered farms, fields and woodland. The name Burngreave was first recorded in 1440 as Byron Greve, meaning Bryons Wood. This is shown in early maps on the site currently occupied by Burngreave Cemetery and along Burngreave Road. During the Tudor period Sheffield began to grow but Burngreave remained on the outskirts. Looking back from the top of Pitsmoor at that time, you would have seen rolling hills and farmland leading down to Ladys Bridge where a cluster of shops and houses had developed around the market place next to Sheffield Castle.

On Andover Street there is a building which is thought to date back to Tudor times. Locally known as the White House, it operated as a fish and chip shop until recently.

Urbanisation and population growth

During the 18th century and 19th century the area remained still largely rural but industry was beginning to have an impact. In the 1820s the town of Sheffield stopped at the Wicker, below Spital Hill. Pitsmoor was just a hamlet through which the main turnpike road ran from Sheffield to Barnsley and Wakefield. Industry in the area was mostly in the form of small workshops, attached to farm buildings, producing knives and tools for a local market. There were no factories as yet. Maps from the 1830s and 40s show farmsteads, fields, some woodland and a few scattered mansions that belonged to the wealthy elite of Sheffield. At this time Burngreave was considered a highly desirable place for rich families to build new homes in. Mansions such as Osgathorpe House and Firs Hill (both now demolished) were built during this period. By 1870 a dramatic transformation had taken place. The arrival of heavy steel and engineering industries, concentrated in the Don Valley, created jobs for migrant workers from all over England and as far away as Ireland. Development of the railways and roads also contributed to the expansion of Sheffield as a centre for craftsmanship and industry.

%2C_from_Andover_Street%2C_Burngreave%2C_Sheffield_-_geograph.org.uk_-_1762639.jpg)

Between 1820 and 1860 the population of Sheffield tripled from just over 65,000 to 185,000. In Burngreave many new houses including a group of cottages built by William Pass and occupied by miners called Pass-houses (now this location is called Passhouses Road),[2] to accommodate the workforce of nearby industries. These were often terraced or constructed around courts and changed the character of the area completely. Neighbourhoods such as Ellesmere and Woodside became established. In the 1870s the writer Alfred Gatty described the view from Osgathorpe down into the Don Valley: “….there stands, as it were, Dantes city of Dis…masses of buildings, from the tops of which issue fire, and smoke, and steam, which cloud the whole scene, however bright the sunshine.” A drawing from 1879 of John Sorbys Spital Hill steel works captures this atmosphere completely.

Despite this grim picture of development, the higher part of Burngreave was far enough away from the noise and pollution to remain popular with Sheffields industrialists and professional classes. Abbeyfield House was built during the late 19th century by William Pass as his own residence. Originally called Pitsmoor Abbey, it first belonged to William Pass, the owner of a local colliery. Then the house was bought by a solicitor, Bernard Wake, who turned it into the family home. He altered the house greatly, adding a sundial, conservatory, greenhouses, a tennis court and outhouses. The gardens were redesigned and a boating lake created around 1883. In the early 20th century Abbeyfield House was occupied by the Greenwood family and then into the possession of the Sheffield Parks Department Training Centre.[3]

By the late 19th century much of the former countryside of Burngreave was covered in houses. Along with these were created the Vestry Hall in 1864 to administer civic functions. Schools, churches, pubs and allotments were also created in the 19th century. The first school, Pitsmoor Village School, was opened in 1836. In 1861 Burngreave cemetery was laid out to accommodate the overflow from local church yards as these were full. A cinema and public baths were built in the early 20th century. By this time, Burngreave was a suburb of Sheffield, still prosperous and considered a pleasant place to live. It did, however, have an interesting mix of wealthy and working class residents. Occasional declines in the fortunes of the cutlery trade resulted in periods of unemployment and great hardship for many poorer families in the area. A cartoon from a newspaper in 1879 shows a soup kitchen operating from the Vestry Hall, turning away barefoot and hungry children.

The World Wars

Burngreave was badly affected by both World Wars. Zeppelin raids killed people and damaged homes in 1916. Again, in 1940, the area was heavily bombed causing much damage to homes and businesses in the area as well as killing and injuring people. In both wars men were sent off as conscripts to fight and their places taken in the factories by women. During the Second World War children were evacuated to the countryside and those who stayed behind went to school in peoples homes as it was considered too risky to operate schools normally.

Since 1945

After the Second World War housing renewal had a major impact on the area. Slum clearance started in earnest and whole neighbourhoods were decanted to other parts of the city whilst the old substandard housing was demolished. In place of the back-to-backs and terraces came new estates of council housing and flats. This changed the character of the area quite dramatically and resulted in many people moving away, never to return. The disruption that many people experienced at this time also affected the sense of community and identity of the area.

In the years immediately after the Second World War, there was a desperate need for labour in Sheffield to rebuild the city and its industries. Around this time Burngreave became home to many new immigrants, arriving from the Caribbean, Pakistan and Yemen. Many found jobs in the steel industry and the hospitals in Sheffield. Later they brought their families to join them and became part of the local community. This was the beginnings of the multicultural community that is Burngreave today. We do know, however, that Asian people had lived in the area even before this period. In Burngreave cemetery there is a grave of an Indian man killed in a colliery accident in Beighton in 1923, called Sultan Mohomed. There is also evidence to suggest that some Somali people settled in the area during the 1930s.

Since the 1970s the area has also become home to refugees from Chile, Somalia, Eritrea, Iraq, Sudan, and several other countries. More recently, Slovakian people have come in search of work. The arrival of people from so many different backgrounds has made Burngreave one of the most ethnically diverse neighbourhoods in Sheffield. This cultural richness is reflected in the number of different languages spoken locally and the variety of food on offer in local restaurants and shops.

The industrial decline of the 1980s and 90s in South Yorkshire has taken its toll on Burngreave. High levels of unemployment resulted in poverty once again and a general decline in the appearance of the area. However Burngreave is now experiencing a change in fortune. This has partly resulted from the determination of local residents to stop the spiral of decay and bring about changes. In addition a huge government funded regeneration programme, Burngreave New Deal for Communities, has been initiated to bring prosperity back to the area. There is a spirit of optimism again, with improvements to houses and green spaces locally. New shops have opened recently to serve the needs of different ethnic communities. It is once again a friendly and welcoming place to live in bustling with life. In late 2011, a Tesco Extra opened on Saville Street, a couple of hundred yards from Spital Hill, the traditional shopping hotspot of the area.

In 2013 and 2014 there has been unrest between Roma Slovak and Yemeni residents in the Page Hall area.[4]

Transport

Bus routes 97 and 98 link Burngreave to Sheffield City Centre.

References

- ↑ "City of Sheffield ward population 2011". Neighbourhood Statistics. Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 10 March 2016.

- ↑ J Edward Vickers, Old Sheffield Town, 1978, page 27

- ↑ J. Edward Vickers, Old Sheffield Town, 1978, page 27

- ↑ "Two arrests over mass brawl on Sheffield street". The Star. 21 May 2014. Retrieved 28 January 2015.

External links

- Burngreave's Local History Sources for the history of Burngreave, produced by Sheffield City Council's Libraries and Archives