Burmese Days

| |

| Author | George Orwell |

|---|---|

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Novel |

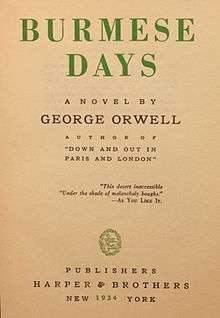

| Publisher | Harper & Brothers (US) |

Publication date | October 1934 |

| Media type | Print (hardback & paperback) |

| Pages | 300 |

| ISBN | 978-0-141-18537-8 |

Burmese Days is a novel by British writer George Orwell. It was first published in the UK in 1934. It is a tale from the waning days of British colonialism, when Burma was ruled from Delhi as a part of British India – "a portrait of the dark side of the British Raj." At its centre is John Flory, "the lone and lacking individual trapped within a bigger system that is undermining the better side of human nature."[1] Orwell's first novel, it describes "corruption and imperial bigotry in a society where, "after all, natives were natives—interesting, no doubt, but finally...an inferior people".[2]

Because of concerns that the novel might be potentially libellous, that Katha was described too realistically, and that some of the characters might be based on real people, it was first published "further afield", in the United States. A British edition, with altered names, appeared a year later. When it was published in the 1930s, Orwell's harsh portrayal of colonial society was felt by "some old Burma hands" to have "rather let the side down". In a letter from 1946, Orwell said "I dare say it's unfair in some ways and inaccurate in some details, but much of it is simply reporting what I have seen".[3]

Background

Orwell spent five years from 1922 to 1927 as a police officer in the Indian Imperial Police force in Burma, (now Myanmar). Burma had become part of the British Empire during the 19th century as an adjunct of British India. The British colonised Burma in stages—it was not until 1885 when they captured the royal capital of Mandalay that Burma as a whole could be declared part of the British Empire. Migrant workers from India and China supplemented the native Burmese population. Although Burma was the wealthiest country in Southeast Asia under British rule, as a colony it was seen very much as a backwater.[4] The image which the English people were meant to uphold in these communities was a huge burden and the majority of them carried expectations all the way from Britain with the intention of maintaining their customs and rule. Among its exports, the country produced 75 percent of the world's teak from up-country forests. When Orwell arrived in the Irrawaddy Delta to begin his career as an imperial policeman, in January 1924, the delta was leading Burma's exports of over three million tons of rice—half the world's supply.[5]:86 Orwell served in a number of locations in Burma. Having spent a year of police training in Mandalay and Maymyo, his postings included Myaungmya, Twante, Syriam, Insein—(north of Rangoon, site of the colony's most secure prison, and now present-day Burma's most notorious jail),[5]:146—Moulmein, and Kathar. Kathar with its luxuriant vegetation, described by Orwell with relish, provided the physical setting for the novel.

Burmese Days was several years in the writing. Orwell was drafting it in Paris during the time he spent there from 1928 to 1929. He was still working on it in 1932 at Southwold while doing up the family home in the summer holidays. By December 1933 he had typed the final version,[6] and in 1934 he delivered it to his agent Leonard Moore for publication by Victor Gollancz, who had published his previous book. Gollancz, smarting from fears of prosecution from another author's work, turned it down because he was worried about charges of libel.[6] Heinemann and Cape turned it down for the same reasons. After demanding alterations, Harpers were prepared to publish it in the United States, where it made its debut in 1934. In the spring of 1935, Gollancz declared that he was prepared to publish Burmese Days provided that Orwell was able to demonstrate it was not based on real people. Extensive checks were made in colonial lists that no British individuals could be confused with the characters. Many of the main European names have since been identified in the Rangoon Gazette and U Po Kyin was the name of a Burmese officer with him at the Police Training School in Mandalay.[7] Gollancz brought out the English version on 24 June 1935.[8]

Plot summary

Burmese Days is set in 1920s imperial Burma, in the fictional district of Kyauktada. The original of Kyauktada is Kathar (formerly spelled Katha), a town where Orwell served. Like Kyauktada it is the head of a branch railway line above Mandalay on the Ayeyarwady (Irrawaddy) River. As the story opens, U Po Kyin, a corrupt Burmese magistrate, is planning to destroy the reputation of the Indian Dr Veraswami. The doctor's main protection is his friendship with John Flory who, as a pukka sahib (European white man), has higher prestige. Dr Veraswami wants the privilege of becoming a member of the British club because he thinks that if his standing with the Europeans is good, U Po Kyin's intrigues against him will not prevail. U Po Kyin begins a campaign to persuade the Europeans that the doctor holds disloyal, anti-British opinions, and believes anonymous letters with false stories about the doctor "will work wonders". He even sends a threatening letter to Flory.

John Flory is a jaded 35-year-old teak merchant. Responsible three weeks of every month for the appropriation of jungle timber, he is friendless among his fellow Europeans and is unmarried.[9]:58 He has a ragged crescent of a birthmark on his face. Flory has become disillusioned with his lifestyle, living in a tiresome expatriate community centred round the European Club in a remote part of the country. On the other hand, he has become so embedded in Burma that it is impossible for him to leave and return to England. Veraswami and Flory are good friends, and Flory often visits the doctor for what the latter delightedly calls "cultured conversation". In these conversations Flory details his disillusionment with the empire. The doctor for his part becomes agitated whenever Flory criticises the Raj and defends the British as great administrators who have built an efficient and unrivalled empire. Flory dismisses these administrators as mere moneymakers, living a lie, "the lie that we're here to uplift our poor black brothers instead of to rob them". Though he finds release with his Burmese mistress, Flory is emotionally dissatisfied. "On the one hand, Flory loves Burma and craves a partner who will share his passion, which the other local Europeans find incomprehensible; on the other hand, for essentially racist reasons, Flory feels that only a European woman is acceptable as a partner".[9]:58

Flory's dilemma seems to be answered when Elizabeth Lackersteen, the orphaned niece of Mr Lackersteen, the local timber firm manager, arrives. Flory saves her when she thinks she is about to be attacked by a small water buffalo. He is immediately taken with her and they spend some time getting close, culminating in a highly successful shooting expedition. After several misses Elizabeth shoots a pigeon, and then a flying bird, and Flory shoots a leopard, promising the skin to Elizabeth as a trophy. Lost in romantic fantasy, Flory imagines Elizabeth to be the sensitive non-racist he so much desires, the European woman who will "understand him and give him the companionship he needed". He turns Ma Hla May, his pretty, scheming Burmese concubine, out of his house. Under the surface, however, Elizabeth is appalled by Flory's relatively egalitarian attitude towards the natives, seeing them as "beastly" while Flory extols the virtues of their rich culture. She is frightened and repelled by the Burmese. Worse still are Flory's interests in high art and literature, which remind Elizabeth of her boondoggling mother who died in disgrace in Paris of ptomaine poisoning as a result of living in squalid conditions while masquerading as a Bohemian artist. Despite these reservations, of which Flory is entirely unaware, she is willing to marry him to escape poverty, spinsterhood, and the unwelcome advances of her perpetually inebriated uncle.

Flory is about to ask her to marry him, but they are interrupted first by her aunt and secondly by an earthquake. Mrs Lackersteen's interruption is deliberate because she has discovered that a military police lieutenant named Verrall is arriving in Kyauktada. As he comes from an extremely good family, she sees him as a better prospect as a husband for Elizabeth. Mrs Lackersteen tells Elizabeth that Flory is keeping a Burmese mistress as a deliberate ploy to send her to Verrall. Indeed, Flory had been keeping a mistress, but had dismissed her almost the moment Elizabeth had arrived. Elizabeth is appalled and falls at the first opportunity for Verrall, who is arrogant and ill-mannered to all but her. Flory is devastated and after a period of exile attempts to make amends by delivering to her the leopard skin. A bungled curing process has left the skin mangy and stinking and the gesture merely compounds his status as a poor suitor. When Flory delivers it to Elizabeth she accepts it regardless of the fact that it stinks and he talks of their relationship, telling her he still loves her. She responds by telling him that unfortunately the feelings aren't mutual and leaves the house to go horse riding with Verrall. When Flory and Elizabeth part ways, Mrs Lackersteen orders the servants to burn the reeking leopard skin, representing the deterioration of Flory and Elizabeth's relationship.

U Po Kyin's campaign against Dr Veraswami turns out to be intended simply to further his aim of becoming a member of the European Club in Kyauktada. The club has been put under pressure to elect a native member and Dr Veraswami is the most likely candidate. U Po Kyin arranges the escape of a prisoner and plans a rebellion for which he intends that Dr Veraswami should get the blame. The rebellion begins and is quickly put down, but a native rebel is killed by acting Divisional Forest Officer, Maxwell. Uncharacteristically courageous, Flory speaks up for Dr Veraswami and proposes him as a member of the club. At this moment the body of Maxwell, cut almost to pieces with dahs by two relatives of the man he had shot, is brought back to the town. This creates tension between the Burmese and the Europeans which is exacerbated by a vicious attack on native children by the spiteful arch-racist timber merchant, Ellis. A large but ineffectual anti-British riot begins and Flory becomes the hero for bringing it under control with some support by Dr Veraswami. U Po Kyin tries to claim credit but is disbelieved and Dr Veraswami's prestige is restored.

Verrall leaves Kyauktada without saying goodbye to Elizabeth and she falls for Flory again. Flory is happy and plans to marry Elizabeth. However, U Po Kyin has not given up. He hires Flory's former Burmese mistress to create a scene in front of Elizabeth during the sermon at church. Flory is disgraced and Elizabeth refuses to have anything more to do with him. Overcome by the loss and seeing no future for himself, Flory kills first his dog, and then himself.

Dr Veraswami is demoted and sent to a different district and U Po Kyin is elected to the club. U Po Kyin's plans have succeeded and he plans to redeem his life and cleanse his sins by financing the construction of pagodas. He dies of apoplexy before he can start building the first pagoda and his wife envisages him returning to life as a frog or rat. Elizabeth eventually marries Macgregor, the deputy commissioner, and lives happily in contempt of the natives, who in turn live in fear of her, fulfilling her destiny of becoming a "burra memsahib" [respectful term given to white European women].

Characters

- John (in some editions, James) Flory: referred to as just "Flory" throughout the novel. He is the central character, a timber merchant in his mid-thirties. He has a long, dark blue birthmark that stretches from his eye to the side of his mouth on his left cheek, and he tries to avoid showing people the left side of his face as he thinks the birthmark is hideous. Whenever he is ashamed or looks down upon himself he remembers his birthmark, a symbol of his weakness. He is very friendly with the Indian Dr Veraswami, and appreciates Burmese culture. This brings him into conflict with members of the club, who dislike his slightly radical views. Because of his rather shy personality and the fact that he dislikes quarrels, he is an easy target in arguments, especially with Ellis. This discourages him from fully advocating for the Burmese. He suffers a great deal emotionally because he is infatuated with Elizabeth. All he can think about is Elizabeth but they have conflicting interests and she does not reciprocate the love. Flory supports the Burmese where as Elizabeth regards them as beasts. Flory wants Elizabeth to appreciate him, especially with his hindering birthmark, yet he wants to support the Burmese. Due to his indecisive personality he is caught between supporting the Burmese and the English. After Elizabeth leaves Flory the second time, he commits suicide.

- Elizabeth Lackersteen: An unmarried English girl who has lost both her parents and comes to stay with her remaining relatives, the Lackersteens, in Burma. Before her flighty mother died, they had lived together in Paris. Her mother fancied herself an artist, and Elizabeth grew to hate the Bohemian lifestyle and cultural connections. Elizabeth is 22, 'tallish for a girl, slender", with fashionably short hair and wears tortoise shell glasses. Throughout the novel, she seeks to marry a man because her aunt keeps pressuring her and she idolises wealth and social class, neither of which she could achieve without a husband during this time period. When she first meets Flory, he falls in love because he values white women over Burmese women. After leaving Flory for the first time, she courts Verrall, who leaves her abruptly without saying goodbye. The second time she leaves Flory (and following his suicide), she marries Deputy Commissioner MacGregor.

- Mr Lackersteen: Elizabeth's uncle and Mrs Lackersteen's husband. Lackersteen is the manager of a timber firm. He is a heavy drinker whose main object in life is to have a "good time". However his activities are curtailed by his wife who is ever watching "like a cat over a bloody mousehole" because ever since she returned after leaving him alone one day to find him surrounded by three naked Burmese girls, she does not trust him alone. Lackersteen's lechery extends to making sexual advances towards his niece, Elizabeth.

- Mrs Lackersteen: Elizabeth's aunt and Mr Lackersteen's wife. Mrs Lackersteen is "a woman of about thirty-five, handsome in a contourless, elongated way, like a fashion plate". She is a classic memsahib, the title used for wives of officials in the Raj. Both she and her niece have not taken to the alien country or its culture. (In Burmese Days Orwell defines the memsahib as "yellow and thin, scandal mongering over cocktails—living twenty years in the country without learning a word of the language."). And because of this, she strongly believes that Elizabeth should get married to an upper class man who can provide her with a home and accompanying riches. She pesters Elizabeth into finding a husband: first she wants her to wed Verrall, then after he leaves, Flory.

- Dr Veraswami: An Indian doctor and a friend of Flory's. He has nothing but respect for the British colonists and often refers to his own kind as being lesser humans than the English, even though many of the British, including Ellis, don't respect him. Veraswami and Flory often discuss various topics, with Veraswami presenting the British point of view and Flory taking the side of the Burmese. Dr Veraswami is targeted by U Po Kyin in pursuit of membership of the European club. Dr Veraswami wants to become a member of the club so that it will give him prestige which will protect him from U Po Kyin's attempts to exile him from the district. Because he respects Flory, he does not pester him to get him admitted into the club. Eventually U Po Kyin's plan to exile Dr Veraswami comes through. He is sent away to work in another run-down hospital elsewhere.

- U Po Kyin: A corrupt and cunning magistrate who is hideously overweight, but perfectly groomed and wealthy. He is 56 and the "U" in his name is his title, which is an honorific in Burmese society. He feels he can commit whatever wicked acts he wants—cheat people of their money, jail the innocent, abuse young girls—because although, "According to Buddhist belief those who have done evil in their lives will spend the next incarnation in the shape of a rat, frog, or some other low animal", he intends to provide against these sins by devoting the rest of his life to good works such as financing the building of pagodas, "and balance the scales of karmic justice".[13] He continues his plans to attack Dr Veraswami, instigating a rebellion as part of the exercise, to make Dr Veraswami look bad and eliminate him as a potential candidate of the club, so he can secure the membership for himself. He believes his status as a member of the club will cease the intrigues that are directed against him. He loses pre-eminence when Flory and Vereswami suppress the riot. After Flory dies, Kyin becomes a member of the European Club. Shortly after his admission into the club he dies, unredeemed, before the building of the pagodas. "U Po has advanced himself by thievery, bribery, blackmail and betrayal, and his corrupt career is a serious criticism of both the English rule that permits his success and his English superiors who so disastrously misjudge his character".

- Ma Hla May: Flory's Burmese mistress who has been with him for two years before he meets Elizabeth. Ma Hla May believes herself to be Flory's unofficial wife and takes advantage of the privileges that come along with being associated with a white man in Burma. Flory has been paying her expenses throughout their time together. However, after he becomes enchanted with Elizabeth, he informs her that he no longer wants anything to do with her. Ma Hla May is distraught and repeatedly blackmails him. Once thrown out of Flory's house, the other villagers dissociate themselves from her and she cannot find herself a husband to support her. Encouraged by U Po Kyin, who has an alternate agenda to ruin Flory's reputation within the club, she approaches Flory in front of the Europeans and creates a dramatic scene so everyone knows of his intimacy with her. This outburst taints Elizabeth's perception of Flory for good. Eventually she goes to work in a brothel elsewhere.

- Ko S'la: Flory's devoted servant since the day he arrived in Burma. They are close to the same age and Ko S’la has since taken care of Flory. Though he serves Flory well, he does not approve of many of his activities, especially his relationship with Ma Hla May and his drinking habits. He believes that Flory should get married. Flory has remained in the same reckless state that he was in upon arriving in Burma. In Ko S’la's eyes, Flory is still a boy. Ko S’la, on the other hand, has moved on with his life as he has taken wives and fathered five children. He pities Flory due to his childish behaviour and his birthmark.

- Lieutenant Verrall: A military policeman who has a temporary posting in the town. He is everything that Flory is not—young, handsome, privileged. He is the youngest son of a peer and looks down on everyone, making no concessions to civility and good manners. His only concern while in town is playing polo. He takes no notice of a person's race, everyone is beneath him. Verrall is smug and self-centered. Encouraged by her aunt, Elizabeth pursues Verrall as a suitor, but he uses her only for temporary entertainment. In the end, he vanishes from town without a word to Elizabeth.

- Mr Macgregor: Deputy Commissioner and secretary of the club. He is upright and well-meaning, although also pompous and self-important. U Po Kyin contacts Mr Macgregor through anonymous letters as he continues his attacks on Dr Veraswami to gain a position in the club. As one of the only single men left in the town, he marries Elizabeth.

- Ellis: A violently racist Englishman who manages a timber company in upper Burma. He is a vulgar and spiteful member of the club who likes stirring up scandals. He believes in the British rule of Burma and that the Burmese people are completely incapable of ruling the country themselves. His hatred of the Burmese culture causes some clashes with Flory due to Flory's friendliness with the Burmese, especially Dr Veraswami. Ellis is in support of U Po Kyin's plan to ruin the reputation of Dr Veraswami and needs no evidence whatsoever of Dr Veraswami's guilt.

Style

Orwell biographer D.J. Taylor notes that, "the most striking thing about the novel is the extravagance of its language: a riot of rococo imagery that gets dangerously out of hand"[10]

Another of Orwell's biographers, Michael Shelden, notes that Joseph Conrad, Somerset Maugham and E. M. Forster have been suggested as possible influences, but believes also that "the ghost of Housman hangs heavily over the book."[11] The writers Stansky and Abrahams, while noting that the character Flory probably had his roots in Captain Robinson, a cashiered ex-officer whom Orwell had met in Mandalay, "with his opium-smoking and native women", affirmed that Flory's "deepest roots are traceable to fiction, from Joseph Conrad's Lord Jim through all those Englishmen gone to seed in the East which are one of Maugham's better-known specialities."[12]:42

Jeffrey Meyers, in a 1975 guide to Orwell's work, wrote of the E. M. Forster connection that, "Burmese Days was strongly influenced by A Passage to India, which was published in 1924 when Orwell was serving in Burma. Both novels concern an Englishman's friendship with an Indian doctor, and a girl who goes out to the colonies, gets engaged and then breaks it off. Both use the Club scenes to reveal a cross-section of colonial society, and both measure the personality and value of the characters by their racial attitudes...But Burmese Days is a far more pessimistic book than A Passage to India, because official failures are not redeemed by successful personal relations."[13]

Orwell himself was to note in Why I Write (1946) that "I wanted to write enormous naturalistic novels with unhappy endings, full of detailed descriptions and arresting similes, and also full of purple passages in which my words were used partly for the sake of their sound. And in fact my first complete novel, Burmese Days...is rather that kind of book."

Themes

Imperialism

Imperialistic views among the main characters differ, as does the public opinion as to the purpose of the British conquest in Burma. Imperialism is defined as the creation and/or maintenance of an unequal economic, cultural, and territorial relationship. This usually occurs between states in the form of an empire, based on domination and subordination.

A lot of discussion based on imperialism takes place within the novel, primarily between Flory and Dr Veraswami. Flory describes imperialism as "the lie that we're here to uplift our poor black brothers rather than to rob them." However his view is ridiculed by his friend, Dr Veraswami, who believes that British rule has helped civilise the people, improve education, and build infrastructure. From Dr Veraswami's perspective, British imperialism has helped him achieve his status as a doctor in colonial Burma. Flory counters this by noting that little manual skill is taught and that the only buildings built are prisons. Furthermore, he suggests that the English brought with them diseases, but Veraswami blames this on the Indians and sees the English as the curers.

Flory views imperialism as a way to make money, commenting that he is only in Burma to finance himself, that this is the only reason why he doesn't want British rule to come to an end. Westfield states that British rule has begun to collapse in Burma, to the point where the natives no longer respect their rulers. Westfield's suggestion that the British should simply leave the country to hasten its descent into anarchy is well received by the other members of their club, even Flory.

Racism

Throughout the novel, there is a stark contrast between the sentiments on race even among the English. While most of the English club members, specifically Ellis and Mr. Lackersteen, have a strong distaste for the Burmese natives, viewing them as "black, stinking swine", there is a sense of opposition to the racism by other club members, like Flory and Mr. Macgregor. Mr Macgregor, the secretary of the club, is the one to raise the issue of admitting a native to their all-white club. Even the mention of this elicits a strong reaction from Ellis, who claims he would rather "die in the ditch" before belonging to the same club as a native. In the end, Mr Macgregor retains his distaste for the Burmese, similar to the other Englishmen. It is rather clear that most of the English see nothing admirable in the Burmese people and instead view them with distaste. Flory is the most accepting of the Burmese, though he shirks from openly sharing his sentiments in the midst of such overwhelming racism. Racism plays an intricate role in what the English view as successful colonisation. They believe that to maintain their power they need to oppress the natives. They do this through their racist attitudes, actions, and beliefs which put the natives lower in the power hierarchy by treating them as lesser humans who need the English aid. Although there is a spectrum of racist sentiment held by the English in Burma, it is ever-present and "a thing native to the very air of India".

Identity

Flory is best described as a person with an identity crisis. He is trapped between his appreciation of Burmese culture and his part in sustaining British imperial rule. He is stuck in a position where he aims to please all, ultimately pleasing no one.

Flory's love of Burmese culture is expressed in various ways. First his relationship with Dr Veraswami is an example of his respect for the culture. Veraswami and Flory often meet socially and argue about the influence of the British. Flory is invariably dismissive of imperial rule's achievements. His very willingness to befriend what his countrymen regard as a "nigger" sets him apart from his British compatriots.

Later in the novel, once Elizabeth is introduced, almost immediately Flory does his best to expose her to Burmese culture. She proves to be uninterested, even resistant. On the other hand, being a white British man, Flory is forced to adhere to the imperialist views Englishmen are expected to hold. As a member of the exclusively British club he is acting as part of the ruling class.

In addition his proven dedication to his job as an timber merchant for the British empire, creates a character who can be seen as a loyal imperialist. A person who is willing to exploit both human and capital resources of the Burmese. Flory's identity can be described as "approval-seeking." He tries his best to integrate his lifestyle with the Englishmen as well as also wanting to be a part of Burmese society. This confusion of identity and the need for approval later leads to his demise as both worlds come crashing down simultaneously.

Reactions

Harpers brought out Burmese Days in the US on 25 October 1934, in an edition of 2,000 copies. In February 1935, just four months after publication, 976 copies were remaindered. The only American review that Orwell himself saw, in the New York Herald Tribune, by Margaret Carson Hubbard, was unfavourable: "The ghastly vulgarity of the third-rate characters who endure the heat and talk ad nausea of the glorious days of the British Raj, when fifteen lashes settled any native insolence, is such that they kill all interest in their doings." A positive review however came from an anonymous writer in the Boston Evening Transcript, for whom the central figure was, "analyzed with rare insight and unprejudiced if inexorable justice", and the book itself praised as full of "realities faithfully and unflinchingly realised."[12]:56-57

On its publication in Britain, Burmese Days earned a review in the New Statesman from Cyril Connolly as follows:[14]

Burmese Days is an admirable novel. It is a crisp, fierce, and almost boisterous attack on the Anglo-Indian. The author loves Burma, he goes to great length to describe the vices of the Burmese and the horror of the climate, but he loves it, and nothing can palliate for him, the presence of a handful of inefficient complacent public school types who make their living there... I liked it and recommend it to anyone who enjoys a spate of efficient indignation, graphic description, excellent narrative, excitement, and irony tempered with vitriol.

Orwell received a letter from the anthropologist Geoffrey Gorer as follows[15]

Will you allow me to tell you how very much indeed I admire your novel Burmese Days: it seems to me an absolutely admirable statement of fact told as vividly and with as little bitterness as possible.

It was as a result of these responses that Orwell renewed his friendship with Connolly, which was to give him useful literary connections, a positive evaluation in Enemies of Promise and an outlet on Horizon. He also became a close friend of Gorer.

In 2013, the Burmese Ministry of Information named the new translation (by Maung Myint Kywe) of Burmese Days the winner of the 2012 Burma National Literature Award's "informative literature" (translation) category.[16] The National Literary Awards are the highest literary awards in Burma.

References

- ↑ Emma Larkin, Introduction, Penguin Classics edition, 2009

- ↑ Back cover description, Penguin Classics, 2009 ISBN 978-0-14-118537-8

- ↑ Introduction, Emma Larkin, Penguin Classics edition, 2009

- ↑ Back cover description, Penguin Books, 1967

- 1 2 Larkin, Ellen (2005). Finding George Orwell in Burma. New York: Penguin Press. ISBN 1-59420-052-1.

- 1 2 Orwell, Sonia and Angus, Ian (eds.). The Collected Essays, Journalism and Letters of George Orwell Volume 1: An Age Like This (1920–1940) (Penguin)

- ↑ Michael Shelden Orwell: The Authorised Biography

- ↑ Burmese Days, p.xvi Penguin 2009 ISBN 978-0-14-118537-8

- 1 2 Orwell for Beginners, David Smith and Michael Mosher. ISBN 0-86316-066-2

- ↑ D. J. Taylor Orwell: The Life Chatto & Windus 2003.

- ↑ Michael Shelden Orwell: The Authorised Biography, Chapter Ten, 'George Orwell, Novelist', William Heinemann 1991

- 1 2 Stansky, Peter; Abrahams, William (1981). Orwell: The Transformation. Granada.

- ↑ Jeffrey Meyers, A Readers Guide to George Orwell, Thames & Hudson 1975, p, 68–69

- ↑ Cyril Connolly Review New Statesman 6 July 1935

- ↑ Letter from Geoffrey Gorer 16 July 1935 Orwell Archive

- ↑ Kyaw Phyo Tha (19 November 2013). "Orwell's 'Burmese Days' Wins Govt Literary Award". The Irrawaddy. Retrieved 22 November 2013.

External links

- "Orwell's Burma", an essay that originally appeared in Time

- Online version,

- The Literary Encyclopedia

- Another look at Burmese Days

- Burmese Days as a “valuable historical document” which “recorded vividly the tensions that prevailed in Burma, and the mutual suspicion, despair, and disgust that crept into Anglo-Burmese relations.”

- Discusses the role that English clubs, like the one in Burmese Days, played in British India

- Discusses how Burmese Days is not a novel but a political statement based on the events that take place in the novel