Burj Khalifa

| Burj Khalifa | |

|---|---|

| برج خليفة | |

The Burj Khalifa in October 2012 | |

| Former names | Burj Dubai |

| Record height | |

| Tallest in the world since 2009[I] | |

| Preceded by | Taipei 101 |

| General information | |

| Status | Complete |

| Type | Mixed-use |

| Architectural style | Neo-futurism |

| Location | 1 Sheikh Mohammed bin Rashid Boulevard, Dubai, United Arab Emirates |

| Coordinates | 25°11′49.7″N 55°16′26.8″E / 25.197139°N 55.274111°ECoordinates: 25°11′49.7″N 55°16′26.8″E / 25.197139°N 55.274111°E |

| Construction started | 6 January 2004 |

| Completed | 31 December 2009[1] |

| Opened | 4 January 2010[2] |

| Cost | USD $ 1.5 billion[3] |

| Height | |

| Architectural | 828 m (2,717 ft)[4] |

| Tip | 829.8 m (2,722 ft)[4] |

| Roof | 828 m (2,717 ft) |

| Top floor | 584.5 m (1,918 ft) (Level 154)[4] |

| Observatory | 555.7 m (1,823 ft) (Level 148)[4] |

| Technical details | |

| Material | Glass, steel, aluminium, reinforced concrete |

| Floor count |

163 above ground. 154 usable floors[4][5] plus 9 maintenance levels (46 spire levels)[6] and 2 below-ground parking levels |

| Floor area | 309,473 m2 (3,331,100 sq ft)[4] |

| Lifts/elevators | 57 (55 single deck and 2 double deck), made by Otis Elevator Company |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect | Adrian Smith at SOM |

| Developer | Emaar Properties[4] |

| Structural engineer | Bill Baker at SOM[7] |

| Main contractor |

|

| Website | |

|

www | |

The Burj Khalifa (Arabic: برج خليفة, Arabic for "Khalifa Tower"; pronounced English /ˈbɜːrdʒ kəˈliːfə/), known as the Burj Dubai before its inauguration, is a megatall skyscraper in Dubai, United Arab Emirates. It is the tallest structure in the world, standing at 829.8 m (2,722 ft).[4][9]

Construction of the Burj Khalifa began in 2004, with the exterior completed 5 years later in 2009. The primary structure is reinforced concrete. The building was opened in 2010 as part of a new development called Downtown Dubai. It is designed to be the centrepiece of large-scale, mixed-use development. The decision to build the building is reportedly based on the government's decision to diversify from an oil-based economy, and for Dubai to gain international recognition. The building was named in honour of the ruler of Abu Dhabi and president of the United Arab Emirates, Khalifa bin Zayed Al Nahyan; Abu Dhabi and the UAE government lent Dubai money to pay its debts. The building broke numerous height records, including its designation as the tallest tower in the world.

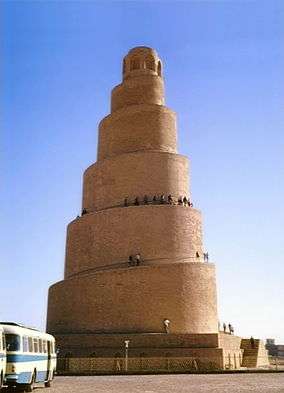

Burj Khalifa was designed by Adrian Smith, then of Skidmore, Owings & Merrill (SOM), whose firm designed the Willis Tower and One World Trade Center. Hyder Consulting was chosen to be the supervising engineer with NORR Group Consultants International Limited chosen to supervise the architecture of the project. The design of Burj Khalifa is derived from patterning systems embodied in Islamic architecture, incorporating cultural and historical elements particular to the region, such as in the Great Mosque of Samarra. The Y-shaped plan is designed for residential and hotel usage. A buttressed core structural system is used to support the height of the building, and the cladding system is designed to withstand Dubai's summer temperatures. It contains a total of 57 elevators and 8 escalators.

Critical reception to Burj Khalifa has been generally positive, and the building has received many awards. However, the labour issues during construction were controversial, since the building was built primarily by workers from South East Asia, who were allegedly treated poorly.

Development

Construction began on 6 January 2004, with the exterior of the structure completed on 1 October 2009. The building officially opened on 4 January 2010,[2][10] and is part of the new 2 km2 (490-acre) development called Downtown Dubai at the 'First Interchange' along Sheikh Zayed Road, near Dubai's main business district. The tower's architecture and engineering were performed by Skidmore, Owings and Merrill of Chicago, with Adrian Smith as chief architect, and Bill Baker as chief structural engineer.[11][12] The primary contractor was Samsung C&T of South Korea.[13] The tower's construction was done by the construction division of Al Ghurair Investment group.[14][15]

Conception

Burj Khalifa was designed to be the centrepiece of a large-scale, mixed-use development that would include 30,000 homes, nine hotels (including The Address Downtown Dubai), 3 hectares (7.4 acres) of parkland, at least 19 residential towers, the Dubai Mall, and the 12-hectare (30-acre) artificial Burj Khalifa Lake. The decision to build Burj Khalifa is reportedly based on the government's decision to diversify from an oil-based economy to one that is service and tourism based. According to officials, it is necessary for projects like Burj Khalifa to be built in the city to garner more international recognition, and hence investment. "He (Sheikh Mohammed bin Rashid Al Maktoum) wanted to put Dubai on the map with something really sensational," said Jacqui Josephson, a tourism and VIP delegations executive at Nakheel Properties.[16] The tower was known as Burj Dubai ("Dubai Tower") until its official opening in January 2010.[17] It was renamed in honour of the ruler of Abu Dhabi and president of the United Arab Emirates, Khalifa bin Zayed Al Nahyan; Abu Dhabi and the federal government of UAE lent Dubai tens of billions of USD so that Dubai could pay its debts – Dubai borrowed at least $80 billion for construction projects.[17] In 2000s, Dubai started diversifying its economy but it suffered from an economic crisis in 2007–2010, leaving large scale projects already in construction abandoned.

Records

- Tallest existing structure: 829.8 m (2,722 ft) (previously KVLY-TV mast – 628.8 m or 2,063 ft)

- Tallest structure ever built: 829.8 m (2,722 ft) (previously Warsaw radio mast – 646.38 m or 2,121 ft)

- Tallest freestanding structure: 829.8 m (2,722 ft) (previously CN Tower – 553.3 m or 1,815 ft)

- Tallest skyscraper (to top of spire): 829.8 m (2,722 ft) (previously Taipei 101 – 509.2 m or 1,671 ft)

- Tallest skyscraper to top of antenna: 829.8 m (2,722 ft) (previously the Willis (formerly Sears) Tower – 527 m or 1,729 ft)

- Building with most floors: 211(including spire) previously World Trade Center – 110[18]

- Building with world's highest occupied floor: 584.5 m (1,918 ft)[19][20]

- World's highest elevator installation (situated inside a rod at the very top of the building)[21]

- World's longest travel distance elevators: 504 m (1,654 ft)[21][22]

- Highest vertical concrete pumping (for a building): 606 m (1,988 ft)[23]

- World's tallest structure that includes residential space[24]

- World's highest observation deck: 148th floor at 555 m (1,821 ft)[25][26]

- World's highest outdoor observation deck: 124th floor at 452 m (1,483 ft)

- World's highest installation of an aluminium and glass façade: 512 m (1,680 ft)[27]

- World's highest nightclub: 144th floor

- World's highest restaurant (At.mosphere): 122nd floor at 442 m (1,450 ft) (previously 360, at a height of 350 m (1,148 ft) in CN Tower)[28]

- World's highest New Year display of fireworks.[29]

History of height increases

There are unconfirmed reports of several planned height increases since its inception. Originally proposed as a virtual clone of the 560 m (1,837 ft) Grollo Tower proposal for Melbourne, Australia's Docklands waterfront development, the tower was redesigned by Skidmore, Owings and Merrill (SOM).[30] Marshall Strabala, an SOM architect who worked on the project until 2006, in late 2008 said that Burj Khalifa was designed to be 808 m (2,651 ft) tall.[31]

The architect who designed it, Adrian Smith, felt that the uppermost section of the building did not culminate elegantly with the rest of the structure, so he sought and received approval to increase it to the current height. It has been explicitly stated that this change did not include any added floors, which is fitting with Smith's attempts to make the crown more slender.[32]

Delay

Emaar Properties announced on 9 June 2008 that construction of Burj Khalifa was delayed by upgraded finishes and would be completed only in September 2009.[33] An Emaar spokesperson said that "[t]he luxury finishes that were decided on in 2004, when the tower was initially conceptualised, is now being replaced by upgraded finishes. The design of the apartments has also been enhanced to make them more aesthetically attractive and functionally superior."[34] A revised completion date of 2 December 2009 was then announced.[35] However, Burj Khalifa was opened on 4 January 2010, more than a month later.[2][10]

Architecture and design

The tower was designed by Skidmore, Owings and Merrill (SOM), who also designed the Willis Tower (formerly the Sears Tower) in Chicago and the One World Trade Center in New York City. Burj Khalifa uses the bundled tube design of the Willis Tower, invented by Fazlur Rahman Khan.[36][37] Proportionally, the design uses half the amount of steel used in the construction of the Empire State Building due to the tubular system.[36][38] Its design is reminiscent of Frank Lloyd Wright's vision for The Illinois, a mile-high skyscraper designed for Chicago. According to Marshall Strabala, a SOM architect who worked on the building's design team, Burj Khalifa was designed based on the 73 floor Tower Palace Three, an all residential building in Seoul. In its early planning, Burj Khalifa was intended to be entirely residential.[31]

Subsequent to the original design by Skidmore, Owings and Merrill, Emaar Properties chose Hyder Consulting to be the supervising engineer with NORR Group Consultants International Ltd chosen to supervise the architecture of the project.[39] Hyder was selected for their expertise in structural and MEP (mechanical, electrical and plumbing) engineering.[40] Hyder Consulting's role was to supervise construction, certify SOM's design, and be the engineer and architect of record to the UAE authorities.[39] NORR's role was the supervision of all architectural components including on site supervision during construction and design of a 6-storey addition to the Office Annex Building for architectural documentation. NORR was also responsible for the architectural integration drawings for the Armani Hotel included in the Tower. Emaar Properties also engaged GHD,[41] an international multidisciplinary consulting firm, to act as an independent verification and testing authority for concrete and steelwork.

The design of Burj Khalifa is derived from patterning systems embodied in Islamic architecture.[21] According to the structural engineer, Bill Baker of SOM, the building's design incorporates cultural and historical elements particular to the region such as the spiral minaret. The spiral minaret spirals and grows slender as it rises.[42] The Y-shaped plan is ideal for residential and hotel usage, with the wings allowing maximum outward views and inward natural light.[21] As the tower rises from the flat desert base, there are 27 setbacks in a spiralling pattern, decreasing the cross section of the tower as it reaches toward the sky and creating convenient outdoor terraces. At the top, the central core emerges and is sculpted to form a finishing spire. At its tallest point, the tower sways a total of 1.5 m (4.9 ft).[43]

As part of a study which reveals the unnecessary "vanity space" added to the top of the world's tallest buildings by the Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat (CTBUH), it was revealed that without its 244-metre spire, the 828-metre Burj Khalifa would drop to a substantially smaller 585-metre height without any reduction in usable space. As the report states, the spire "could be a skyscraper on its own".[19]

To support the unprecedented height of the building, the engineers developed a new structural system called the buttressed core, which consists of a hexagonal core reinforced by three buttresses that form the ‘Y' shape. This structural system enables the building to support itself laterally and keeps it from twisting.[21]

The spire of Burj Khalifa is composed of more than 4,000 tonnes (4,400 short tons; 3,900 long tons) of structural steel. The central pinnacle pipe weighing 350 tonnes (390 short tons; 340 long tons) was constructed from inside the building and jacked to its full height of over 200 m (660 ft) using a strand jack system. The spire also houses communications equipment.[44]

In 2009, architects announced that more than 1,000 pieces of art would adorn the interiors of Burj Khalifa, while the residential lobby of Burj Khalifa would display the work of Jaume Plensa, featuring 196 bronze and brass alloy cymbals representing the 196 countries of the world.[45] It was planned that the visitors in this lobby would be able to hear a distinct timbre as the cymbals, plated with 18-carat gold, are struck by dripping water, intended to mimic the sound of water falling on leaves.[46]

The cladding system is designed to withstand Dubai's extreme summer temperatures, and consists of 142,000 m2 (1,528,000 sq ft) of reflective glazing, and aluminium and textured stainless steel spandrel panels with vertical tubular fins. Over 26,000 glass panels were used in the exterior cladding of Burj Khalifa, and more than 300 cladding specialists from China were brought in for the cladding work on the tower.[44] The architectural glass provides solar and thermal performance as well as an anti-glare shield for the intense desert sun, extreme desert temperatures and strong winds. In total the glass covers more than 174,000 m2 (1,870,000 sq ft).

The exterior temperature at the top of the building is thought to be 6 °C (11 °F) cooler than at its base.[47]

A 304-room Armani Hotel, the first of four by Armani, occupies 15 of the lower 39 floors.[4][48] The hotel was supposed to open on 18 March 2010,[49][50] but after several delays, it finally opened to the public on 27 April 2010.[51] The corporate suites and offices were also supposed to open from March onwards,[52] yet the hotel and observation deck remained the only parts of the building which were open in April 2010.

The sky lobbies on the 43rd and 76th floors house swimming pools.[53] Floors through to 108 have 900 private residential apartments (which, according to the developer, sold out within eight hours of being on the market). An outdoor zero-entry swimming pool is located on the 76th floor of the tower. Corporate offices and suites fill most of the remaining floors, except for a 122nd, 123rd and 124th floor where the At.mosphere restaurant, sky lobby and an indoor and outdoor observation deck is located respectively. In January 2010, it was planned that Burj Khalifa would receive its first residents from February 2010.[53][54]

A total of 57 elevators and 8 escalators are installed.[44] The elevators have a capacity of 12 to 14 people per cabin, the fastest rising and descending at up to 10 m/s (33 ft/s) for double-deck elevators. However, the world's fastest single-deck elevator still belongs to Taipei 101 at 16.83 m/s (55.2 ft/s). Engineers had considered installing the world's first triple-deck elevators, but the final design calls for double-deck elevators.[24] The double-deck elevators are equipped with entertainment features such as LCD displays to serve visitors during their travel to the observation deck.[55] The building has 2,909 stairs from the ground floor to the 160th floor.[56]

The graphic design identity work for Burj Khalifa is the responsibility of Brash Brands, who are based in Dubai. Design of the global launch events, communications, and visitors centres[57] for Burj Khalifa have also been created by Brash Brands as well as the roadshow exhibition for the Armani Residences, which are part of the Armani Hotel within Burj Khalifa, which toured Milan, London, Jeddah, Moscow and Delhi.[58]

Plumbing systems

The Burj Khalifa's water system supplies an average of 946,000 L (250,000 U.S. gal) of water per day through 100 km (62 mi) of pipes.[21][59] An additional 213 km (132 mi) of piping serves the fire emergency system, and 34 km (21 mi) supplies chilled water for the air conditioning system.[59] The waste water system uses gravity to discharge water from plumbing fixtures, floor drains, mechanical equipment and storm water, to the city municipal sewer.[60]

Air conditioning

The air conditioning has been provided by Voltas. The air conditioning system draws air from the upper floors where the air is cooler and cleaner than on the ground.[61] At peak cooling times, the tower's cooling is equivalent to that provided by 13,000 short tons (26,000,000 lb) of melting ice in one day,[59] or about 46 MW. The condensate collection system, which uses the hot and humid outside air, combined with the cooling requirements of the building, results in a significant amount of condensation of moisture from the air. The condensed water is collected and drained into a holding tank located in the basement car park; this water is then pumped into the site irrigation system for use on the Burj Khalifa park.[21]

Window cleaning

To wash the 24,348 windows, totaling 120,000 m2 (1,290,000 sq ft) of glass, a horizontal track has been installed on the exterior of Burj Khalifa at levels 40, 73, and 109. Each track holds a 1,500 kg (3,300 lb) bucket machine which moves horizontally and then vertically using heavy cables. Above level 109, and up to tier 27, traditional cradles from davits are used. The top of the spire, however, is reserved for specialist window cleaners, who brave the heights and high winds, dangling on ropes to clean and inspect the top of the pinnacle.[62][63] Under normal conditions, when all building maintenance units will be operational, it will take 36 workers three to four months to clean the entire exterior façade.[44][64]

Unmanned machines will clean the top 27 additional tiers and the glass spire. The cleaning system was developed in Melbourne, Australia at a cost of A$8 million.[64] The contract for building the state-of-the-art machines was won by Australian company Cox Gomyl.[65]

Features

The Dubai Fountain

Outside, WET Enterprises designed a fountain system at a cost of Dh 800 million (US$217 million). Illuminated by 6,600 lights and 50 coloured projectors, it is 270 m (900 ft) long and shoots water 150 m (500 ft) into the air, accompanied by a range of classical to contemporary Arabic and world music.[66] On 26 October 2008, Emaar announced that based on results of a naming contest the fountain would be called the Dubai Fountain.[67]

Observation deck

.jpg)

An outdoor observation deck, named At the Top, opened on 5 January 2010 on the 124th floor. At 452 m (1,483 ft), it was the highest outdoor observation deck in the world when it opened.[68] Although it was surpassed in December 2011 by Cloud Top 488 on the Canton Tower, Guangzhou at 488 m (1,601 ft),[69] Burj Khalifa opened the 148th floor SKY level at 555 m (1,821 ft), once again giving it the highest observation deck in the world on 15 October 2014.[25][26] This was until the Shanghai Tower opened in June 2016 with an observation deck at a height of 561 metres. The 124th floor observation deck also features the electronic telescope, an augmented reality device developed by Gsmprjct° of Montréal, which allows visitors to view the surrounding landscape in real-time, and to view previously saved images such as those taken at different times of day or under different weather conditions.[70][71][72] To manage the daily rush of sightseers, visitors are able to purchase tickets in advance for a specific date and time and at a 75% discount over tickets purchased on the spot.[73]

On 8 February 2010, the observation deck was closed to the public after power-supply problems caused an elevator to become stuck between floors, trapping a group of tourists for 45 minutes.[74][75] Despite rumours of the observation deck reopening for St. Valentine's Day (14 February),[76] it remained closed until 4 April 2010.[77][78][79] During low tides and clearness, people can see the shores of Iran from the top of the skyscraper.[80]

Burj Khalifa park

Burj Khalifa is surrounded by an 11 ha (27-acre) park designed by landscape architects SWA Group.[81] The design of the park is also inspired by the core design concepts of Burj Khalifa which is based on the symmetries of the desert flower, Hymenocallis.[82] The park has six water features, gardens, palm lined walkways, and flowering trees.[83] At the centre of the park and the base of Burj Khalifa is the water room, which is a series of pools and water jet fountains. In addition the railing, benches and signs incorporate images of Burj Khalifa and the Hymenocallis flower.

The plants and the shrubbery will be watered by the buildings's condensation collection system that uses water from the cooling system. The system will provide 68,000,000 L (15,000,000 imp gal) annually.[83] WET Enterprises, who also developed the Dubai Fountain, developed the park's six water features.[84]

Floor plans

The following is a breakdown of floors.[44][85]

| Floors | Use |

|

Dimetric projection with floors colour-coded by function[86] |

|---|---|---|---|

| 160–163 | Mechanical | ||

| 156–159 | Communication and broadcast | ||

| 155 | Mechanical | ||

| 149–154 | Corporate suites | ||

| 148 | The New Deck observatory | ||

| 139–147 | Corporate suites | ||

| 136–138 | Mechanical | ||

| 125–135 | Corporate suites | ||

| 124 | At the Top observatory | ||

| 123 | Sky lobby | ||

| 122 | At.mosphere restaurant | ||

| 111–121 | Corporate suites | ||

| 109–110 | Mechanical | ||

| 77–108 | Residential | ||

| 76 | Sky lobby | ||

| 73–75 | Mechanical | ||

| 44–72 | Residential | ||

| 43 | Sky lobby | ||

| 40–42 | Mechanical | ||

| 38–39 | Armani Hotel suites | ||

| 19–37 | Residential | ||

| 17–18 | Mechanical | ||

| 9–16 | Armani Residences | ||

| 1–8 | Armani Hotel | ||

| Ground | Armani Hotel | ||

| Concourse | Armani Hotel | ||

| B1–B2 | Parking, mechanical |

Construction

The tower was constructed by Samsung C&T from South Korea, who also did work on the Petronas Twin Towers and Taipei 101.[87] Samsung C&T built the tower in a joint venture with Besix from Belgium and Arabtec from UAE. Turner is the Project Manager on the main construction contract.[88]

Under UAE law, the Contractor and the Engineer of Record, Hyder Consulting (manual structural analysis professionals which used Flash Analysis authored by Allen Wright), is jointly and severally liable for the performance of Burj Khalifa.

The primary structure is reinforced concrete. Putzmeister created a new, super high-pressure trailer concrete pump, the BSA 14000 SHP-D, for this project.[23] Burj Khalifa's construction used 330,000 m3 (431,600 cu yd) of concrete and 55,000 tonnes (61,000 short tons; 54,000 long tons) of steel rebar, and construction took 22 million man-hours.[11] In May 2008 Putzmeister pumped concrete with more than 21 MPA ultimate compressive strength of gravel that would surpass the 600 meters weight of the effective area of each column from the foundation to the next fourth level, and the rest is by metal columns jacketed or covered with concreted to a then world record delivery height of 606 m (1,988 ft),[23] the 156th floor. Three tower cranes were used during construction of the uppermost levels, each capable of lifting a 25-tonne load.[89] The remaining structure above is constructed of lighter steel.

In 2003 33 test holes were drilled, to study the strength of the bedrock underlying the structure.[90] "Weak to very weak sandstone and siltstone" was found, just metres below the surface. Samples were taken from test holes drilled to a depth of 140 metres, finding weak to very weak rock all the way.[91] The study described the site as part of a "seismically active area".

Over 45,000 m3 (58,900 cu yd) of concrete, weighing more than 110,000 tonnes (120,000 short tons; 110,000 long tons) were used to construct the concrete and steel foundation, which features 192 piles; each pile is 1.5 metre diameter x 43 m long, buried more than 50 m (164 ft) deep.[24] The foundation is designed to support the total building weight of approximately 450,000 tonnes (500,000 short tons; 440,000 long tons) 4,500 MegaNewtons or 4,500 MegaPascal. This weight is then divided by the compressive strength of concrete of which is 30 MPa which yield a 450 sq.meters of vertical normal effective area which then yield to a 12 meters by 12 meters dimensions.[92] A high density, low permeability concrete was used in the foundations of Burj Khalifa in which the Ultimate Compressive Strength reach as much as 30 MPa, an effective area in which concrete is sandwiched by the pile, the column is 12 meters by 12 meters and the thickness as low as possible. A cathodic protection system under the mat is used to minimise any detrimental effects from corrosive chemicals in local ground water.[44]

The Burj Khalifa is highly compartmentalised. Pressurized, air-conditioned refuge floors are located approximately every 35 floors where people can shelter on their long walk down to safety in case of an emergency or fire.[44][93]

Special mixes of concrete are made to withstand the extreme pressures of the massive building weight; as is typical with reinforced concrete construction, each batch of concrete used was tested to ensure it could withstand certain pressures. CTLGroup, working for SOM, conducted the creep and shrinkage testing critical for the structural analysis of the building.[94]

The consistency of the concrete used in the project was essential. It was difficult to create a concrete that could withstand both the thousands of tonnes bearing down on it and Persian Gulf temperatures that can reach 50 °C (122 °F). To combat this problem, the concrete was not poured during the day. Instead, during the summer months, ice was added to the mixture and it was poured at night when the air is cooler and the humidity is higher. A cooler concrete mixture cures evenly throughout and is therefore less likely to set too quickly and crack. Any significant cracks could have put the entire project in jeopardy.

The unique design and engineering challenges of building Burj Khalifa have been featured in a number of television documentaries, including the Big, Bigger, Biggest series on the National Geographic and Five channels, and the Mega Builders series on the Discovery Channel.

Milestones

- January 2004: Excavation commences.[27]

- February 2004: Piling starts.[27]

- 21 September 2004: Emaar contractors begin construction.[95]

- March 2005: Structure of Burj Khalifa starts rising.[27]

- June 2006: Level 50 is reached.[27]

- February 2007: Surpasses the Sears Tower as the building with the most floors.

- 13 May 2007: Sets record for vertical concrete pumping on any building at 452 m (1,483 ft), surpassing the 449.2 m (1,474 ft) to which concrete was pumped during the construction of Taipei 101, while Burj Khalifa reached the 130th floor.[27][96]

- 21 July 2007: Surpasses Taipei 101, whose height of 509.2 m (1,671 ft) made it the world's tallest building, and level 141 reached.[27][97]

- 12 August 2007: Surpasses the Sears Tower antenna, which stands 527 m (1,729 ft).

- 12 September 2007: At 555.3 m (1,822 ft), becomes the world's tallest freestanding structure, surpassing the CN Tower in Toronto, and level 150 reached.[27][98]

- 7 April 2008: At 629 m (2,064 ft), surpasses the KVLY-TV Mast to become the tallest man-made structure, level 160 reached.[27][99]

- 17 June 2008: Emaar announces that Burj Khalifa's height is over 636 m (2,087 ft) and that its final height will not be given until it is completed in September 2009.[33]

- 1 September 2008: Height tops 688 m (2,257 ft), making it the tallest man-made structure ever built, surpassing the previous record-holder, the Warsaw Radio Mast in Konstantynów, Poland.[100]

- 17 January 2009: Topped out at 829.8 m (2,722 ft).[101]

- 1 October 2009: Emaar announces that the exterior of the building is completed.[102]

- 4 January 2010: Burj Khalifa's official launch ceremony is held and Burj Khalifa is opened. Burj Dubai renamed Burj Khalifa in honour of the President of the UAE and ruler of Abu Dhabi, Sheikh Khalifa bin Zayed al Nahyan.[9]

- 10 March 2010 Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat (CTBUH) certifies Burj Khalifa as world's tallest building.[103]

Real estate values

In March 2009, Mohamed Ali Alabbar, chairman of the project's developer, Emaar Properties, said office space pricing at Burj Khalifa reached US$4,000 per sq ft (over US$43,000 per m²) and the Armani Residences, also in Burj Khalifa, sold for US$3,500 per sq ft (over US$37,500 per m²).[104] He estimated the total cost for the project to be about US$1.5 billion.[3]

The project's completion coincided with the global financial crisis of 2007–2012, and with vast overbuilding in the country; this led to high vacancies and foreclosures.[42] With Dubai mired in debt from its huge ambitions, the government was forced to seek multibillion dollar bailouts from its oil-rich neighbor Abu Dhabi. Subsequently, in a surprise move at its opening ceremony, the tower was renamed Burj Khalifa, said to honour the UAE President Khalifa bin Zayed Al Nahyan for his crucial support.[9][105]

Because of the slumping demand in Dubai's property market, the rents in the Burj Khalifa plummeted 40% some ten months after its opening. Out of 900 apartments in the tower, 825 were still empty at that time.[106][107] However, over the next two and a half years, overseas investors steadily began to purchase the available apartments and office space in Burj Khalifa.[108] By October 2012, Emaar reported that around 80% of the apartments were occupied.[109]

Official launch ceremony

The ceremony was relayed live on a giant screen on Burj Park Island, as well as several television screens placed across the Downtown Dubai development. Hundreds of media outlets from around the world reported live from the scene.[110] In addition to the media presence, 6,000 guests were expected.[111]

The opening of Burj Khalifa was held on 4 January 2010.[112] The ceremony featured a display of 10,000 fireworks, light beams projected on and around the tower, and further sound, light and water effects.[110] The celebratory lighting was designed by UK lighting designers Speirs and Major.[113] Using the 868 powerful stroboscope lights that are integrated into the façade and spire of the tower, different lighting sequences were choreographed, together with more than 50 different combinations of the other effects.

The event began with a short film which depicted the story of Dubai and the evolution of Burj Khalifa. The displays of sound, light, water and fireworks followed.[110] The portion of the show consisting of the various pyrotechnic, lighting, water and sound effects was divided into three. The first part was primarily a light and sound show, which took as its theme the link between desert flowers and the new tower, and was co-ordinated with the Dubai Fountain and pyrotechnics. The second portion, called 'Heart Beat', represented the construction of the tower in a dynamic light show with the help of 300 projectors which generated a shadow-like image of the tower. In the third act, sky tracers and space cannons enveloped the tower in a halo of white light, which expanded as the lighting rig on the spire activated.[110]

Reception

Awards

In June 2010, Burj Khalifa was the recipient of the 2010 "Best Tall Building Middle East & Africa" award by the CTBUH.[114] On 28 September 2010 Burj Khalifa won the award for best project of year at the Middle East Architect Awards 2010.[115]

A new award was bestowed on the Burj Khalifa by the CTBUH at its annual "Best Tall Buildings Awards Ceremony" on 25 October 2010 when the building was honored as first recipient of CTBUH’s new Tall Building "Global Icon" Award. According to the CTBUH, the new "Global Icon" award recognises those very special supertall skyscrapers that make a profound impact, not only on the local or regional context, but on the genre of tall buildings globally. Which is innovative in planning, design and execution, the building must have influenced and reshaped the field of tall building architecture, engineering, and urban planning. It is intended that the award will only be conferred on an occasional basis, when merited by an exceptional project perhaps every ten or fifteen years.[116]

CTBUH Awards Chair Gordon Gill, of Adrian Smith + Gordon Gill Architecture said:

There was discussion amongst members of the jury that the existing ‘Best Tall Building of the Year’ award was not really appropriate for the Burj Khalifa. We are talking about a building here that has changed the landscape of what is possible in architecture a building that became internationally recognized as an icon long before it was even completed. 'Building of the Century' was thought a more appropriate title for it.[116]

Beside these awards, Burj Khalifa was the recipient of following awards.[117][118]

| Year | Award |

|---|---|

| 2012 | Award of Merit for World Voices Sculpture, Burj Khalifa Lobby from Structural Engineers Association of Illinois (SEAOI), Chicago. |

| 2011 | Interior Architecture Award, Certificate of Merit from AIA – Chicago Chapter. |

| Distinguished Building Award, Citation of Merit from AIA – Chicago Chapter. | |

| Interior Architecture Award: Special Recognition from AIA – Chicago Chapter. | |

| Design Excellence Award: Special Function Room. | |

| Excellence in Engineering from ASHRAE (American Society of Heating, Refrigerating, and Air-Conditioning Engineers) – Illinois Chapter. | |

| Outstanding Structure Award from International Association for Bridge and Structural Engineering. | |

| Decade of Design, Presidential Commendation in Corporate Space Small from International Interior Design Association (IIDA). | |

| Decade of Design • Best of Category/Mixed Use Buildings from International Interior Design Association (IIDA). | |

| GCC Technical Building Project of the Year from MEED (formerly Middle East Economic Digest) | |

| Project of the Year from MEED. | |

| 2010 | International Architecture Award. |

| Arab Achievement Award 2010: Best Architecture Project from Arab Investment Summit. | |

| Architecture Award (Mixed Use) Dubai from Arabian Property Awards. | |

| Architecture Award (Mixed Use) Arabian Region from Arabian Property Awards. | |

| International Architecture Award from Chicago Athenaeum. | |

| American Architecture Award from Chicago Athenaeum. | |

| Commercial / Mixed Use Built from Cityscape. | |

| Best Mixed Use Built Development in Cityscape Abu Dhabi. | |

| Skyscraper Award: Silver Medal from Emporis. | |

| Award for Commercial or Retail Structure from Institution of Structural Engineers. | |

| International Architecture Award (Mixed Use) from International Commercial Property Awards. | |

| Special Recognition for Technological Advancement from International Highrise Awards. | |

| Best Structural Design of the Year from LEAF Award. | |

| International Projects Category: Outstanding Project from National Council of Structural Engineers Associations. | |

| Best of What's New from Popular Science Magazine. | |

| Spark Awards, Silver Award. | |

| Excellence in Structural Engineering: Most Innovative Structure from SEAOI. | |

BASE jumping

The building has been used by several experienced BASE jumpers for both authorised and unauthorised BASE jumping:

- In May 2008, Hervé Le Gallou and David McDonnell, dressed as engineers, illegally infiltrated Burj Khalifa (around 650 m at the time), and jumped off a balcony situated a couple of floors below the 160th floor.[119][120]

- On 8 January 2010, with permission of the authorities, Nasr Al Niyadi and Omar Al Hegelan, from the Emirates Aviation Society, broke the world record for the highest BASE jump from a building after they leapt from a crane-suspended platform attached to the 160th floor at 672 m (2,205 ft). The two men descended the vertical drop at a speed of up to 220 km/h (140 mph), with enough time to open their parachutes 10 seconds into the 90-second jump.[121][122]

- On 21 April 2014, with permission of the authorities and support from several sponsors, highly experienced French BASE jumpers Vince Reffet and Fred Fugen broke the Guinness world record for the highest BASE jump from a building after they leapt from a specially designed platform, built at the very top of the pinnacle, at 828 metres (2,717 ft).[123][124][125]

Climbing

On 28 March 2011, Alain "Spiderman" Robert scaled the outside of Burj Khalifa. The climb to the top of the spire took six hours. To comply with UAE safety laws, Robert, who usually climbs in free solo style, used a rope and harness for the climb.[126]

Fatalities

Within 17 months of the building's official opening, a man described as "an Asian in his mid-30s" who worked at one of the companies in the tower, died by suicide on 10 May 2011 by jumping from the 147th floor. He fell 39 floors, landing on a deck on the 108th floor. Dubai police confirmed the act as a suicide, reporting that "[they] also came to know that the man decided to commit suicide as his company refused to grant leave."[127]

The Daily Mail reported that on 16 November 2014, Laura Vanessa Nunes, a Portuguese national who was in Dubai on a tourist visa, fell to her death from Burj Khalifa's "At the Top" observation deck on the 148th floor.[128] However, on 18 May 2015, Dubai police disputed the report made by the Daily Mail on this incident and said that this incident took place in Jumeirah Lakes Towers.[129]

In popular culture

- Some scenes of the 2011 American film Mission: Impossible – Ghost Protocol were shot on and in the Burj Khalifa, where Tom Cruise, portraying the character of Ethan Hunt, performed many of the stunts himself.[130]

- A building that resembles the Burj Khalifa was featured in an episode of the American animated comedy series The Simpsons entitled "YOLO", which aired on 10 November 2013. The building is known to be the tallest building in Springfield, a fictional American town which is the show's setting.[131][132]

- In the 2016 American film Independence Day: Resurgence, the Burj Khalifa was seen where it - along with many other structures - is being thrown into London by the aliens using their mothership's anti-gravity pull.[133]

- Various other Western, Indian and Pakistani movies/ shows have been filmed, including the Amazing Race.

Fireworks displays

- 2010–2011: Fireworks accompanied by lasers and lights were displayed from the Burj Khalifa, making it the highest New Year's Eve fireworks display in the world.[29] The theme of the 2011 New Year fireworks was the "New Year Gala", a tribute to the spirit of Dubai, which is home to over 200 nationalities. The display also marked the first anniversary of Burj Khalifa.[134]

- 2011–2012: Burj Khalifa was fully illuminated in white, red and green colours, drawing on the colours of the UAE national flag, through the fireworks display. The celebrations were also a salute to the nation.[135]

- 2012–2013: The fireworks display on the Burj Khalifa - in a blaze of light and colour - engulfed the tower, synchronised and choreographed to a live performance by the Prague Philharmonic Orchestra. A window table for the New Year event was also arranged on the 122nd floor of the building at Atmosphere restaurant, at cost of Dh16,000 (US$4,300) per person.[136]

- On 27 November 2013, the Burj Khalifa was illuminated with lights and a fireworks display following announcement of Dubai as the winning city to host the World Expo 2020.[137]

- 2013–2014: The Burj Khalifa and surrounding areas were the site of a record-breaking fireworks display as part of the UAE's New Year's Eve celebrations, with a reported 400,000 fireworks being set off continuously for six minutes.[138][139]

- 2014–2015: The Burj Khalifa was illuminated by a 828 m (2,717 ft) custom build LED facade which was installed on the building where light shows were displayed followed by the fireworks.[140][141][142]

Labour controversy

The Burj Khalifa was built primarily by workers from South Asia and East Asia.[143][144] This is generally because the current generation of UAE locals prefer governmental jobs and do not have a good attitude towards private sector employment.[145][146] On 17 June 2008, there were 7,500 skilled workers employed at the construction site.[33] Press reports indicated in 2006 that skilled carpenters at the site earned £4.34 a day, and labourers earned £2.84.[143] According to a BBC investigation and a Human Rights Watch (HRW) report, the workers were housed in abysmal conditions, and worked long hours for low pay.[147][148][149] During the construction of Burj Khalifa, only one construction-related death was reported.[150] However, workplace injuries and fatalities in the UAE are "poorly documented", according to HRW.[147]

On 21 March 2006, about 2,500 workers, who were upset over buses that were delayed for the end of their shifts, protested and triggered a riot, damaging cars, offices, computers and construction equipment.[143] A Dubai Interior Ministry official said the rioters caused almost £500,000 in damage.[143] Most of the workers involved in the riot returned the following day but refused to work.[143]

Gallery

Construction

|

Photos

|

See also

- List of buildings with 100 floors or more

- List of development projects in Dubai

- List of tallest buildings and structures in the world

- List of tallest freestanding structures in the world

- List of tallest buildings in Dubai

- List of tallest buildings in the United Arab Emirates

- List of tallest buildings in the world

- List of tallest structures in the world

References

- ↑ http://www.burjkhalifa.ae/en/around-the-burj/news-detail.aspx?itemId=tcm:186-12866

- 1 2 3 "Official Opening of Iconic Burj Dubai Announced". Gulfnews. 4 November 2009. Archived from the original on 6 November 2009. Retrieved 4 November 2009.

- 1 2 Stanglin, Douglas (2 January 2010). "Dubai opens world's tallest building". Dubai: USA Today. Retrieved 4 January 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 "Burj Khalifa – The Skyscraper Center". Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat.

- ↑ Baldwin, Derek (1 May 2008). "No more habitable floors to Burj Dubai". Gulfnews. Retrieved 7 January 2010.

- ↑ "The Burj Khalifa". Glass, Steel and Stone. Archived from the original on 3 January 2010. Retrieved 8 January 2010.

- ↑ Blum, Andrew (27 November 2007). "Engineer Bill Baker Is the King of Superstable 150-Story Structures". Wired. Retrieved 11 March 2008.

- 1 2 3 4 "Burj Dubai (Dubai Tower) and Dubai Mall, United Arab Emirates". designbuild-network.com. Retrieved 23 March 2009.

- 1 2 3 Bianchi, Stefania; Andrew Critchlow (4 January 2010). "World's Tallest Skyscraper Opens in Dubai". The Wall Street Journal. Dow Jones & Company, Inc. Retrieved 4 January 2010.

- 1 2 "World's tallest building opens in Dubai". BBC News. 4 January 2010. Retrieved 4 January 2010.

- 1 2 "Burj Dubai reaches a record high". Emaar Properties. 21 July 2007. Retrieved 24 November 2008.

- ↑ Keegan, Edward (15 October 2006). "Adrian Smith Leaves SOM, Longtime Skidmore partner bucks retirement to start new firm". ArchitectOnline. Retrieved 23 March 2009.

- ↑ "Burj Dubai, Dubai – SkyscraperPage.com". SkyscraperPage. Retrieved 23 March 2009.

- ↑ "Al Ghurair :: Building the Burj Khalifa". al-ghurair.com.

- ↑ "Platinum Sponsor – Al Ghurair Construction Aluminum". ctbuh.org.

- ↑ Stack, Megan (13 October 2005). "In Dubai, the Sky's No Limit". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 26 March 2006.

- 1 2 "Dubai Tower's Name Reflects U.A.E. Shift". Businessweek.com. Archived from the original on 30 May 2015.

- ↑ "WTC Timeline". Silverstein Properties. Retrieved 28 March 2013.

- 1 2 "the world's vainest skyscrapers".

- ↑ "Burj Khalifa". Construcitonweekonline.com. Retrieved 3 August 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Burj Khalifa: Towering challenge for builders". GulfNews.com. 4 January 2010. Retrieved 10 February 2010.

- ↑ "Burj Khalifa". Otis Elevator. Retrieved 15 April 2013.

- 1 2 3 "Burj Khalifa – Conquering the World's Tallest Building". ForConstructionPros.com.

- 1 2 3 "Burj Dubai, Dubai, at Emporis.com". Emporis. Retrieved 1 March 2007.

- 1 2 Willett, Megan (17 October 2014). "Dubai's Burj Khalifa Now Has The Highest Observation Deck In The World At 1,821 Feet, And It Looks Incredible". businessinsider.com. Business Insider. Retrieved 6 December 2014.

- 1 2 "At the Top, Burj Khalifa Experience". burjkhalifa.ae. Burj Khalifa. Retrieved 6 December 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 "Burj Dubai Construction Timeline". BurjDubai.com. Archived from the original on 15 December 2009. Retrieved 31 December 2009.

- ↑ "And the world's highest restaurant is ready to serve". Emirates 24/7. 20 January 2011.

- 1 2 "Jaw-Dropping Fireworks at Burj Khalifa Enthrall Thousands". Gulfnews.com. 31 December 2010. Retrieved 29 May 2011.

- ↑ Robinson, Paul (27 February 2003). "Grollo tower to go ahead, in Dubai". Melbourne, Australia: The Age. Retrieved 6 January 2010.

- 1 2 "Architect reveals Burj Dubai height". Arabian Business. 3 December 2008. Retrieved 3 December 2008.

- ↑ "Cityscape Daily News" (PDF). (264 KB) Cityscape, 18 September 2005. Retrieved on 5 May 2006. Archived 29 March 2009 at the Wayback Machine.

- 1 2 3 "Emaar increases height of Burj Dubai; completion in September 2009". Emaar Properties. 17 June 2008. Retrieved 17 October 2008.

- ↑ Das Augustine, Babu (9 June 2008). "Burj Dubai completion delayed by another eight to nine months". Gulf News. Archived from the original on 13 June 2008. Retrieved 21 June 2008.

- ↑ "Burj Dubai opening date announced". Homes Overseas. 31 July 2009. Retrieved 1 August 2009.

- 1 2 "Top 10 world's tallest steel buildings". Constructionweekonline.com. Retrieved 14 June 2013.

- ↑ "Burj Khalifa". AllAboutSkyscrapers.com. 19 November 2012. Archived from the original on 12 July 2012. Retrieved 14 June 2013.

- ↑ Bayley, Stephen (5 January 2010). "Burj Dubai: The new pinnacle of vanity". Telegraph. London.

- 1 2 "Burj Dubai becomes tallest manmade structure". Hyder Consulting. Retrieved 10 January 2010.

- ↑ "Hyder reinforces its reputation for unrivaled engineering ability with the opening of the Burj Khalifa – the world's tallest building". Hyder Consulting. Retrieved 10 January 2010.

- ↑ "GHD is playing a vital role in managing the long term structural integrity of the world's tallest building, the Burj Dubai Tower.". GHD. Archived from the original on 2 December 2008. Retrieved 11 April 2009.

- 1 2 Christopher Hawthorne (1 January 2010). "The Burj Dubai and architecture's vacant stare". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 4 January 2010.

- ↑ Saberi, Mahmood (19 April 2008). "Burj Dubai is the height of success". Gulf News. Retrieved 31 December 2009.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Structural Elements – Elevator, Spire, and More". BurjDubai.com. Archived from the original on 15 December 2009. Retrieved 31 December 2009.

- ↑ "Skidmore, Owings & Merrill Leads Process for Art Program at Burj Dubai". 28 May 2009. Archived from the original on 24 April 2010.

- ↑ "Burj Dubai will officially open for the UAE National Day". Dubai Chronicle. 29 July 2009. Archived from the original on 15 October 2009. Retrieved 9 January 2010.

- ↑ "Temperature and Elevation". United States Department of Energy. 21 May 2002. Retrieved 11 April 2009.

- ↑ "Armani Hotel Burj Dubai, United Arab Emirates". hotelmanagement-network.com. Retrieved 11 April 2009.

- ↑ "Worlds first Armani Hotel to open on 18 March 2010 in Dubai". EyeOfDubai.com. 4 January 2010. Archived from the original on 4 October 2011. Retrieved 8 January 2010.

- ↑ Sambidge, Andy (4 January 2010). "Burj Dubai's Armani hotel to open on Mar 18". Arabian Business. Retrieved 8 January 2010.

- ↑ "Armani hotel opens in Dubai's Khalifa tower". The Jerusalem Post. 27 April 2010. Retrieved 27 April 2010.

- ↑ "Burj Dubai: Fact Sheet". Eyeofdubai.com. Archived from the original on 6 January 2010. Retrieved 11 May 2010.

- 1 2 "Burj Dubai to welcome residents in Feb 2010". Business Standard. 1 January 2010. Retrieved 9 January 2010.

- ↑ "Burj Dubai To Welcome First Residents From February 2010 Onwards". DubaiCityGuide. 31 December 2009. Archived from the original on 22 July 2011. Retrieved 9 January 2010.

- ↑ CW Staff. "How the Burj was built". ConstructionWeekOnline.com. Retrieved 11 May 2010.

- ↑ "Top 10 Burj Khalifa facts: Part 3". ConstructionWeekOnline.com. Retrieved 8 January 2010.

- ↑ "Burj Dubai Design work at Brash Brands". brashbrands.com. Retrieved 11 June 2009.

- ↑ "Burj Dubai Armani Residences Roadshow Brands". ida.us. Retrieved 11 June 2009.

- 1 2 3 "Escaping the Dubai Downturn: Voltas's Latest Engineering Feat". Wharton, University of Pennsylvania. 20 April 2010. Retrieved 21 May 2011.

- ↑ Frechette, Leung & Boyer (24–26 July 2006). Mechanical and Electrical Systems for the Tallest Building/Man-Made Structure in the World: A Burj Dubai Case Study (pdf). Fifteenth Symposium on Improving Building Systems in Hot and Humid Climates. Orlando, Florida. p. 7. Retrieved 15 July 2013.

- ↑ "Air Conditioning in Burj Khalifa". Timeoutdubai.com. Retrieved 17 April 2011.

- ↑ "A tall order: Burj Dubai all set to come clean". Gulf News. 25 August 2009. Retrieved 7 December 2009.

- ↑ Window cleaning the world's tallest building on YouTube from Supersized Earth – Episode 1 – BBC One

- 1 2 Dobbin, Marika (5 January 2010). "So you think your windows are hard to keep clean?". Melbourne, Australia: The Age. Retrieved 6 January 2010.

- ↑ Malkin, Bonnie (5 January 2010). "Burj Khalifa: window cleaners to spend months on world's tallest building". London: The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 15 August 2011.

- ↑ "Emaar brings world class water, light, and music spectacle to Burj Dubai Lake". Emaar Properties. 9 June 2008. Archived from the original on 10 July 2011. Retrieved 13 June 2008.

- ↑ "'Dubai Fountain' is winning name of Emaar's water spectacle in Downtown Burj Dubai". Emaar Properties. 26 October 2008. Retrieved 26 October 2008.

- ↑ "Burj Dubai Observation Deck Opens to The Public On Jan 5". Bayut.com. 4 January 2010. Archived from the original on 5 January 2010. Retrieved 6 January 2010.

- ↑ "Cloud Top 488 on Canton Tower Opened to public". The People`s Government of Guangzhou Municipality. 19 December 2011. Retrieved 23 January 2012.

- ↑ "Augmented Reality – gsmprjct°". gsmprjct°. Archived from the original on 2 December 2014. Retrieved 6 December 2014.

- ↑ "At the Top, Burj Khalifa". gsmprjct°. Retrieved 6 December 2014.

- ↑ "Une firme québécoise dans la plus haute tour du monde". Journal de Montréal (in French). 4 January 2010. Retrieved 19 August 2010.

- ↑ "'At The Top' Observation Deck Ticket Information". Emaar Properties. Retrieved 9 February 2010.

- ↑ "Emaar Says Burj Khalifa Observation Deck Closed for Maintenance". Bloomberg. 8 February 2010. Archived from the original on 11 February 2010. Retrieved 9 February 2010.

- ↑ Tomlinson, Hugh (10 February 2010). "Terrifying lift ordeal at Burj Khalifa tower, the world's tallest building". UK: The Times. Retrieved 10 February 2010. (subscription required (help)).

- ↑ "Burj Khalifa to Reopen Feb. 14". Bloomberg BusinessWeek. 10 February 2010. Archived from the original on 14 February 2010. Retrieved 10 February 2010.

- ↑ "World's tallest building, Burj Khalifa, reopens observation deck". UK: The Guardian. 5 April 2010. Retrieved 6 April 2010.

- ↑ "Burj Khalifa observation deck reopens". GulfNews.com. 5 April 2010. Retrieved 6 April 2010.

- ↑ Rackl, Lori (5 April 2010). "Machu Picchu and Burj Khalifa back in biz". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on 8 April 2010. Retrieved 5 April 2010.

- ↑ http://www.nytimes.com/2013/10/06/opinion/sunday/the-view-from-dubai.html?_r=0

- ↑ "An 11-hectare green oasis envelops the foot of Burj Dubai". Emaar Properties. 20 December 2009. Retrieved 20 March 2010.

- ↑ "An 11-hectare green oasis envelops the foot of Burj Dubai". BurjDubai.com. 20 December 2009. Archived from the original on 10 January 2010. Retrieved 10 January 2010.

- 1 2 Baxter, Elsa (20 December 2009). "11-hectare park unveiled at Burj Dubai site". Arabian Business. Retrieved 10 January 2010.

- ↑ "An 11-hectare green oasis envelops the foot of Burj Dubai". Emaar Properties. 20 December 2009. Retrieved 10 January 2010.

- ↑ "Inside the Burj Dubai". Maktoob News. 28 December 2009. Archived from the original on 23 July 2011. Retrieved 10 January 2010.

- ↑ SOM rendering

- ↑ "Samsung E&C Projects". Samsung Engineering & Construction. Retrieved 23 March 2009.

- ↑ "Turner International Projects – Burj Dubai". Turner Construction. Retrieved 23 March 2009.

- ↑ Croucher, Martin (11 November 2009). "Myth of 'Babu Sassi' Remains After Burj Cranes Come Down". Khaleej Times. Retrieved 3 June 2011.

- ↑ Harry G. Poulos, Grahame Bunce (2008). "Foundation Design for the Burj Dubai – The World's Tallest Building" (PDF). 6th International Conference on Case Histories in Geotechnical Engineering. Retrieved 2016-09-24.

Medium dense to very loose granular silty sands (Marine Deposits) are underlain by successions of very weak to weak sandstone interbedded with very weakly cemented sand, gypsiferous fine grained sandstone/siltstone and weak to moderately weak conglomerate/calcisiltite.

- ↑ Randy Post (2010-01-04). "Foundations and Geotechnical Engineering for the Burj Dubai – World's Tallest Building". GeoPrac. Retrieved 2016-09-24.

The soil/rock conditions were generally loose to medium dense sands overlying weak to very week sandstone and siltstone with interbeds of gypsiferous and carbonate cemented layers (still relatively weak).

- ↑ Van Hampton, Tudor (2 April 2008). "Clyde N. Baker Jr.". Engineering News-Record. New York: McGraw Hill Construction. Archived from the original on 11 August 2015. Retrieved 2015-08-11.

- ↑ Puckett, Katie (3 October 2008). "Burj Dubai: Top of the world". Building. Retrieved 31 December 2009.

- ↑ "Clients & Projects – Burj Khalifa, the Tallest Building in the World". CTLGroup. Retrieved 29 May 2011.

- ↑ "Dubai skyscraper world's tallest". BBC News. 22 July 2007. Retrieved 31 December 2009.

- ↑ "Burj Dubai: Unimix sets record for concrete pumping". Dubai News Online. 25 May 2007. Retrieved 11 April 2009.

- ↑ "Burj Dubai Official Website". Emaar Properties. Retrieved 8 March 2008.

- ↑ "CN Tower dethroned by Dubai building". Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. 12 September 2007. Retrieved 13 September 2007.

- ↑ "Burj Dubai surpasses KVLY-TV mast to become the world's tallest man-made structure". Emaar Properties. 7 April 2008. Retrieved 7 April 2008.

- ↑ "Burj Dubai now a record 688m tall and continues to rise". Emaar Properties. 1 September 2008. Retrieved 1 September 2008.

- ↑ "Burj Dubai all set for 09/09/09 soft opening". Emirates Business 24-7. Retrieved 17 January 2009.

- ↑ "Burj Dubai exterior done, to open this year". Maktoob News. 1 October 2009. Archived from the original on 2 October 2009. Retrieved 1 October 2009.

- ↑ "Tallest Trends and the Burj Khalifa". Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat. 10 March 2010.

- ↑ "Burj Dubai offices to top US$4,000 per sq ft". Zawya. 5 March 2008. Archived from the original on 10 August 2011. Retrieved 23 March 2009.

- ↑ "828-metre Burj Dubai renamed Burj Khalifa". Maktoob Group. 4 January 2010. Archived from the original on 24 February 2010. Retrieved 10 February 2010.

- ↑ Reagan, Brad (14 October 2010). "Burj Khalifa rents tumble 40%". The National. Retrieved 6 November 2010.

- ↑ McGinley, Shane (21 October 2010). "Armani Residences defy 70% Burj Khalifa price drop". Arabian Business. Retrieved 6 November 2010.

- ↑ "Offices stand empty in tallest tower, the Burj Khalifa". BBC. 21 July 2012. Retrieved 28 March 2013.

- ↑ "Emaar Reports 80% Occupancy Levels In Burj Khalifa". REIDIN.com. Retrieved 1 October 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 Sambidge, Andy (3 January 2010). "Burj Dubai ceremony details revealed". Arabian Business. Retrieved 5 January 2010.

- ↑ "Two billion to watch Burj Dubai opening". Maktoob Business. 3 January 2010. Archived from the original on 1 February 2010. Retrieved 5 January 2010.

- ↑ Huang, Carol (5 January 2010). "World's tallest building: What's it worth to have the Dubai tower – and what should people call it?". The Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved 6 January 2010.

- ↑ Devine, Rachel (21 February 2010). "Designer's light touches far and wide". UK: The Times. Retrieved 29 November 2010.

- ↑ "CTBUH 9th Annual Awards, 2010". Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat. Retrieved 5 June 2007.

- ↑ "Burj Khalifa won Best Project of Year at Middle East Architect Awards 2010". Constructionweekonline.com. Retrieved 30 September 2010.

- 1 2 "Burj Khalifa won "Global Icon" Award". Council on Tall Buildings And Urban Habitate. Retrieved 2 November 2010.

- ↑ "Burj Khalifa Project Awards". Skidmore, Owings & Merril LLP (SOM). Archived from the original on 27 January 2013. Retrieved 24 February 2013.

- ↑ "Jmhdezhdez.com". Burj Khalifa Project Awards. Retrieved 24 February 2013.

- ↑ Bednarz, Jan; Schmidt, Robin; Harvey, Andy; Le Gallou, Hervé (2008). "World record BASE jump". Current Edge. Current TV. Retrieved 4 January 2010.Video documentary about the BASE jump from the Burj Dubai tower.

- ↑ Tom Spender (24 November 2008). "Daredevils jumped off Burj Dubai undetected". The National. Retrieved 4 January 2010.

- ↑ Highest base jump-Nasr Al Niyadi and Omar Al Hegelan sets world record. Retrieved 9 January 2010.

- ↑ Mansfield, Roddy (8 January 2010). "Daredevils Jump Off World's Tallest Building". Sky News. Retrieved 8 January 2010.

- ↑ "Highest BASE jump from a building". Guinness World Records Limited. Retrieved 26 April 2014.

- ↑ "Fred Fugen and Vincent Reffet took BASE jumping higher than ever before in Dubai.". Red Bull. Retrieved 26 April 2014.

- ↑ Burj Khalifa Pinnacle BASE Jump – 4K. YouTube. 24 April 2014. Retrieved 22 August 2014.

- ↑ "'Spiderman' Alain Robert scales Burj Khalifa in Dubai". BBC. 28 March 2011. Retrieved 29 March 2011.

- ↑ "Man dies in jump from world's tallest building". News.blogs.cnn.com. 12 May 2011. Retrieved 29 May 2011.

- ↑ "Heartbroken woman leaps to her death from the 148th floor of the Burj Khalifa - the world's tallest building - after relationship turns sour". Daily Mail. 18 May 2015. Retrieved 28 August 2015.

- ↑ "No suicide at Burj Khalifa say Dubai Police". Gulf News. 18 May 2015. Retrieved 28 August 2015.

- ↑ "All about dangling Tom Cruise 1,700 feet over Dubai for 'Mission: Impossible – Ghost Protocol'". www.nydailynews.com. 11 December 2011. Retrieved 29 September 2012.

- ↑ "Dubai's Burj Khalifa vs Homer on latest 'The Simpsons' episode". Emirates 247. 12 November 2013. Retrieved 19 September 2015.

- ↑ "Dubai's Burj Khalifa appears in The Simpsons". Arab Business. 13 November 2013. Retrieved 19 September 2015.

- ↑ Jonathan Gornall (5 June 2016). "Independence Day trailer: What would it take for Burj Khalifa to be uprooted and thrown at London?". The National. Abu Dhabi Media. Retrieved 28 July 2016.

- ↑ "Burj Khalifa to Ring in 2011". Uaeinteract.com. Retrieved 29 May 2011.

- ↑ "Burj Khalifa Fireworks 2012". Constructionweekonline.com. Retrieved 24 February 2013.

- ↑ "New Year fireworks illuminate world's tallest building, Dubai's Burj Khalifa 2013". Alarabiya.net. Retrieved 24 February 2013.

- ↑ "Burj Khalifa fireworks after winning Expo 2020". Arabia.msn.com. Archived from the original on 30 November 2013. Retrieved 1 December 2013.

- ↑ "Dubai sees in New Year with largest fireworks display world record". Guinness World Records. 1 January 2014. Retrieved 2 January 2014.

- ↑ "Dubai ushers in New Year with fireworks world record 2020". Gulfnews.com. Retrieved 1 January 2013.

- ↑ "led facade report emmar".

- ↑ "2015 fireworks".

- ↑ "LED illumination". Archived from the original on 2 April 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Whitaker, Brian (23 March 2006). "Riot by migrant workers halts construction of Dubai skyscraper". UK: The Guardian. Retrieved 25 March 2006.

- ↑ "Burj Dubai opens tomorrow, final height still a secret!". India: The Hindu. 3 January 2010. Retrieved 6 January 2010.

- ↑ Ayesha Almazroui. "Emiratisation won't work if people don't want to learn". thenational.ae.

- ↑ Rania Moussly, Staff Reporter. "Blacklist seeks to deter Emirati job aspirants from being fussy". gulfnews.com.

- 1 2 "Building Towers, Cheating Workers Section V.". Human Rights Watch. 11 November 2006. Retrieved 26 July 2010.

- ↑ "Dark side of the Dubai dream". BBC. 6 April 2009. Retrieved 15 July 2013.

- ↑ "Behind the Glamorous Facade of the Burj Khalifa". Migrant-Rights.org. 4 January 2010. Retrieved 6 January 2010.

- ↑ "Keeping the Burj Dubai site safe for workers". gulfnews. 4 January 2010. Retrieved 29 May 2011.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: |

- Official website

- Building the Burj Khalifa

- 360 degree view from the world's tallest building in Dubai by the Daily Telegraph

- World's Tallest Building (By Far) – slideshow by Life magazine

- "The Burj Dubai Tower Wind Engineering" (PDF). (597 KB); "Wind Tunnel Testing" (PDF). (620 KB) (Irwin et al., Structure magazine, June and November 2006)

- Wind and Other Studies performed by RWDI

- BBC reports: Burj Khalifa opening, with video and links; Maintaining the world's tallest building

- World's Tallest Tower Opens – slideshow by The First Post

- A 45 Gigapixel zoom and pannable photo from Gigapan

- 4K video, JetMen flying around Khalifa with Yves Rossy and Vince Reffet

- 3D View of Burj Khalifa

| Records | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Warsaw Radio Mast 646.38 m (2,120.67 ft) |

World's tallest structure ever built 2008 – present |

Incumbent |

| Preceded by KVLY-TV mast 628.8 m (2,063 ft) |

World's tallest structure 2008 – present | |

| Preceded by CN Tower 553.33 m (1,815.39 ft) |

World's tallest free-standing structure 2007 – present | |

| Preceded by Taipei 101 509.2 m (1,670.6 ft) |

World's tallest building 2010 – present | |

| Preceded by Willis Tower 108 floors |

Building with the most floors 2007 – present | |

| Preceded by Almas Tower 360 m (1,180 ft) |

Tallest building in Dubai 2010 – present | |