Bull Ring, Birmingham

Bullring Shopping Centre, Birmingham | |

| Location | Birmingham, England, UK |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 52°28′39.72″N 1°53′39.04″W / 52.4777000°N 1.8941778°WCoordinates: 52°28′39.72″N 1°53′39.04″W / 52.4777000°N 1.8941778°W |

| Opening date | 4 September 2003 |

| Developer | The Birmingham Alliance |

| Management | Tim Walley |

| Owner | |

| Architect | Benoy |

| No. of stores and services | 140[1] |

| No. of anchor tenants | 3 (Selfridges, Debenhams, TK Maxx[2][3]) |

| Total retail floor area | 125,300 square metres (1,349,000 sq ft)[4] |

| No. of floors | 4 (3 accessible from outside) |

| Parking | 3,100[5] |

| Website | http://www.bullring.co.uk/ |

The Bull Ring is a major commercial area of central Birmingham. It has been an important feature of Birmingham since the Middle Ages, when its market was first held. Two shopping centres have been built in the area; in the 1960s, and then in 2003; the latter is styled as one word, Bullring.

The site is located on the edge of the sandstone city ridge which results in the steep gradient towards Digbeth. The slope drops approximately 15 metres (49 ft) from New Street to St Martin's Church.[6]

The current shopping centre was the busiest in the United Kingdom in 2004 with 36.5 million visitors.[7] It houses one of only four Selfridges department stores, the fourth largest Debenhams and Forever 21. Consequently, the centre has been a huge success, attracting customers from all over the world.[8]

History

.jpg)

The market legally began in 1154 when Peter de Bermingham, a local landowner, obtained a Charter of Marketing Rights from King Henry II.[9] Initially, a textile trade began developing in the area and it was first mentioned in 1232 in a document, in which one merchant is described as a business partner to William de Bermingham and being in the ownership of four weavers, a smith, a tailor and a purveyor. Seven years later, another document described another mercer in the area. Within the next ten years, the area developed into a leading market town and a major cloth trade was established.

The name Mercer Street is first mentioned in the Survey of Birmingham of 1553. This was a result of the prominence of the area in the cloth trade. In the 16th century and 17th century, Mercer Street rapidly developed and became cramped. In the early 18th century Mercer Street was known as Spicer Street, reflecting the growing grocery and meat trade that had begun to take over from the cloth trade. By the end of the century the street was known as Spiceal Street. Despite being overcrowded and cramped, many houses on the street had gardens as indicated by an advertisement for a residential property in 1798. Houses were constructed close to St Martin's Church, eventually encircling it. These became known as the Roundabout Houses.[10]

On a map produced by Westley in 1731, other markets had developed nearby including food, cattle and corn markets with other markets located nearby on the High Street. This corn market was moved to the Corn Exchange on Carrs Lane in 1848. The Bull Ring developed into the main retail market area for Birmingham as the town grew into a modern industrial city.

The earliest known building for public meetings in the town with any architectural record is the High Cross, which stood within the Bull Ring. The last known construction work was in 1703; it was demolished in 1784. It was also known as the Old Cross, to distinguish it from the Welch Cross, and was also nicknamed the Butter Cross due to farmwives selling dairy produce beneath its arches.[10]

A series of events in Birmingham's political history saw the area become a popular meeting place for demonstrations and speeches from leaders of working class movements during the 1830s and 1840s.

In 1839, the Bull Ring was the location of the Bull Ring Riots, which resulted in widespread vandalism and destruction of property. It prompted fears amongst the town's residents at the council's inability to prevent or control the riots and led to speculation that the council was tolerant of lawlessness.[11][12] Because of disorderly behaviour at fairs, in 1861 the area, along with Smithfield and Digbeth, became the only place in central Birmingham where fairs were permitted. In 1875, all fairs were banned from the town.[13]

The area around the market site developed and, by the Victorian era, a large number of shops were operating there. Immigrants set up businesses such as flower-sellers and umbrella vendors. The Lord Nelson statue became the location for preaching and political protests. Well-known preachers of the time were nicknamed Holy Joe and Jimmy Jesus.[14]

Markets in the Bull Ring

In the late 18th century, street commissioners were authorised to buy and demolish houses in the town centre, including houses surrounding the Bull Ring, and to centre all market activity in the area. This was a result of new markets being established across the city in scattered locations creating severe congestion. Demolition of these properties began slowly; however, after the Act of 1801, the speed of demolition increased and by 1810 all properties in the area had been cleared as according to the 1810 Map of Birmingham by Kempson. During the clearance, small streets such as The Shambles, Cock (or Well) Street and Corn Cheaping, which had existed before the Bull Ring, were removed. The Shambles was originally a row of butchers' stores, situated close to the road leading from the location where bulls were slaughtered.[10]

A wide area fronting St Martin's Church formed the marketplace. The Street Commissioners decided that a sheltered market hall was needed. They bought the market rights from the lord of the manor and, by 1832, all properties on site had been purchased, with exception of two, whose owners demanded a higher price. To fund the purchase of these properties, two buildings were constructed either side of the market hall and the leases sold at auction. Construction of the Market Hall, designed by Charles Edge (an architect of Birmingham Town Hall), began in February 1833. It was completed by Dewsbury and Walthews at a cost of £20,000 (£44,800 if the price of acquiring the land is included) and opened on 12 February 1835 and contained 600 market stalls. The building was grand and the façade consisted of stone mined from Bath, Somerset. Two grand Doric columns supported both wide entrances. At the end of the market day, metal gates were pulled in front of the entrances.

In the centre of the 365-foot (111 m) long, 180-foot (55 m) wide and 60-foot (18 m) tall hall was an ornate bronze fountain, given by the Street Commissioners upon their retirement in 1851. The base was made from Yorkshire sandstone and was 460 centimetres (180 in) in diameter. It was in the form of a Greek tazza and cost £900. On the inside of the bowl were eight lions' heads from which water was ejected. The entire fountain was 640 centimetres (250 in) tall and in the centre was a 150 centimetres (59 in) tall statue called the Messenger and Sons. The statue consisted of four children representative of each of Birmingham's main four industries; gun making, glass-blowing, bronzing and engineering. The fountain was inaugurated by the Chairman of the Market Committee, John Cadbury, on 24 December 1851. The fountain was removed in 1880 with the intention of re-erecting it in Highgate Park later that year but this did not happen and it was destroyed in 1923.[15]

Gas lighting was introduced to the building, which extended the business hours for the market. Installations to the market hall included a clock crafted by William Potts and Sons of Leeds consisting of figures of Guy, Earl of Warwick, the Countess, a retainer and a Saracen. It was moved from the Imperial Arcade at Dale End to the market hall in 1936; however, this was destroyed, along with the rest of the Market Hall, on 25 August 1940 by an incendiary attack.

In 1869, the fish market was completed on the site of the Nelson Hotel (formerly the Dog Inn). The Dog Inn was located at the top end of Spiceal Street and the land above was owned by the Cowper family. The fish market was built upon Cowper Street, named after the family, on Summer Lane. In 1884, a sheltered vegetable market in Jamaica Row was also completed.

The trade of horses prospered in the area with over 3,000 horses for sale at its peak during the 1880s. However this fell into rapid decline; the last horse trading fair took place in 1911 with only eleven horses and one donkey in attendance.

A large amount of the area survived World War II; however, nearby New Street was heavily bombed. Shops sold tax-free products to encourage shoppers to buy them as it was difficult for the public to buy goods even a decade after the end of the war. Woolworths set up on Spiceal Street in the Bull Ring and became a popular shop, becoming the largest store on the street. The old Market Hall remained as an empty shell and was used for small exhibitions and open markets. No repair work was conducted on the building and the arches that housed the windows were bricked up.

Archaeology on the site

As the redevelopment of 2000 began, archaeological excavations were conducted on the site. Finds dated back to the 12th century; a ditch was discovered where the Selfridges store and Park Street car park are now situated. Archaeologists discovered that this was a boundary separating houses from a deer park in an area now occupied by Moor Street Station. Rubbish discovered in the ditch was found to include fragments of misfired pottery with criss-cross patterns, indicating that pottery kilns had been located there in the 13th century. Many leather tanning pits dating to the 17th and 18th centuries were found on the Park Street car park site. These contained fragments of crucibles, pottery vessels in which metal was melted. The residues in these were alloys of copper with zinc, lead and tin. On the site where the Indoor Markets are now located, archaeologists discovered further leather tanning pits, these dating from the 13th century.

Burials had also been discovered in the churchyard of St Martin's dating to the 18th and 19th century. Records of families were used to identify the bodies.

Four information panels providing information on the discoveries and history of the site are located in the Bull Ring at St Martin's Square, Edgbaston Street, Park Street and High Street.

Etymology

The area was first known as Corn Cheaping in reference to the corn market on the site. The name Bull Ring referred to the green within Corn Cheaping that was used for bullbaiting. The 'ring' was a hoop of iron in Corn Cheaping to which bulls were tied for baiting before slaughter.[10] The joining of the two words in the 21st-century development of the area to form Bullring caused controversy amongst some residents and other people who were angry at the change of what was described as an "historic spelling."[16]

The first Birmingham Bull Ring Centre

In 1955, shops began to close down as the redevelopment of the area was proposed. Plans drawn up showed the creation of new roads and the demolition of old ones and all the buildings on the proposed site. Eleven companies submitted plans for the new Bull Ring however, Birmingham City Council elected to go for the proposals submitted by John Laing & Sons[17] which used substantial material from designs by James A. Roberts. Demolition began in the late-1950s beginning with the demolition of the old fish market. Construction commenced in the summer of 1961.

The outdoor market area was opened in June 1962 with 150 stalls within the new Bull Ring, which was still under construction. The demolition of the old Market Hall began in 1963.

In 1964, construction of the Birmingham Bull Ring Centre neared completion. It was a mixture of traditional open-air market stalls and a new indoor shopping centre, the first indoor city-centre shopping centre in the UK.[6] It was opened by the Duke of Edinburgh, Prince Philip alongside Alderman Frank Price and Sir Herbert Manzoni on 29 May 1964 and had cost an estimated £8 million. The shopping centre covered 23 acres (93,000 m2) and had 350,000 sq ft (33,000 m2) of retail trade area. Shortly after opening, the complex was visited by Queen Elizabeth II.

The market area was submerged and had approximately 150 stalls with the majority selling food. It was split by a large road which connected to the inner ring road which was built from 1967 till 1971. There was direct access to New Street Station and the market area could be easily accessed from Moor Street Station. A multi-storey car park was also located within the complex with 500 spaces for cars. Access to roads by foot could be achieved through a network of subways. As part of the development, a nine-storey office block designed by James A. Roberts was built. This was attached to the multi-storey car park. The floors were of reinforced concrete, 12 inches in thickness. A bold illuminated sign by D.R.U. was located on the end wall, facing the city centre.[18]

Jamaica Row and Spiceal Street had been demolished and removed during the development, being replaced by a submerged market area.

There were 140 shop units located on 350,000 square feet (33,000 m2) of room on a 4-acre (16,000 m2) site. There were also 19 escalators, 40 lifts, 96 public doors, six miles (10 km) of air ducting and 33 miles (53 km) of pipe work.[19] The shopping centre was air conditioned and had music played to create an intimate atmosphere within the building.

Near New Street Station was the Old Market Hall which had been damaged by bombing in World war II. This had been left roofless for years before being demolished in 1962 and replaced by Manzoni Gardens; an open space designed for shoppers to relax. In the 1970s a statue of King Kong stood there.

A mural of a bull was located on the side of the building as visitors entered via the road splitting the market area.

The 1960s Bull Ring Centre had problems from the beginning and was very much a product of its era. At the time of its opening it was considered the height of modernity, but higher rentals within the shopping centre meant that traders turned away from it. The public were also less inclined to use the subways and escalators, which stopped working regularly. Also, it did not age well and soon became generally regarded as an unfortunate example of 1960s Brutalist architecture, with its boxy grey concrete design and its isolation within ringroads connected only by pedestrian subways. It was, by the 1980s, much disliked by the public and contributed to the popular conception that Birmingham was a concrete jungle of shopping centres and motorways.[20]

In 2015, Historic England included the four bull ring sculptures designed by Trewin Copplestone which stood outside the shopping centre in a list of public works that have been lost, sold, stolen or destroyed.[21][22]

Redevelopment of the Bull Ring

Early proposals

Plans for redevelopments began in the 1980s, a mere 20 years or so after the centre's completion, with many being just visions. In 1987, the first serious plans were released under a document called "The People's Plan" which had been designed by Chapman Taylor Architects for London and Edinburgh Trust (LET), who had bought the land following the end of Laing's lease. It proposed the full demolition of the Bull Ring Shopping Centre and the construction of a new mall described as "a huge aircraft-carrier settled on the streetscape of the city". The mall was a 500-metre (1,600 ft) long box with three floors.

A pressure group called Birmingham for People was formed who wanted to aid the redevelopment of the Bull Ring. They distributed leaflets of the proposals to 44,000 homes in the city. However, as a result of local opinion, LET were forced to change their proposals.

In 1988, in response to the calls for a new design, LET released a masterplan of numerous buildings with a wide pedestrianised street leading to St Martin's Church. As part of the design, two high rise buildings of a similar height to the Rotunda were proposed to front New Street Station and Moor Street Station. However, lack of local support failed to allow the plans to materialise.[6]

In 1995, LET again amended their designs through work with the public. However, a retail recession meant that the plans could not begin construction and they never developed.[23]

Successful proposal

After the failure of the LET plan, new plans began to surface. In the mid-1990s, another serious proposal was produced and this gained support resulting in the publication of a masterplan. However, soon after the publication of the masterplan, changes were made to the design. In 1998, Selfridges voiced reservations about opening a store in Birmingham due to restrictions on doing so and considered opening a store in Glasgow instead.[24] It was an important part of the planned Redevelopment of Birmingham.

Construction and opening

The successful proposal received planning permission and demolition of the 1960s Bull Ring Shopping Centre commenced in 2000 with the traders moving to the Rag Market in Edgbaston Street. It was replaced by a new design, mixing both traditional market activity with modern retail units. The main contractor was Sir Robert McAlpine.[25] The first building to be completed was the Nationwide Building Society which, while not directly connected to the shopping centre, was part of the development. A new indoor shopping centre, "Bullring" (as the commercial entity is branded) opened on 4 September 2003.[26]

Because a major road and two railway tunnels ran under the northern edge of the site, two levels of retail areas are dramatically suspended from four 45m arched steel trusses, each weighing 120 tonnes, which are supported on piles either side of the railway tunnels.[27] [28]

The first week of trading saw the new shopping centre under considerable pressure due to the large crowds it attracted. On 4 September 2003, the day of opening, some 276,600 people visited the shopping centre.[29]

Design and layout

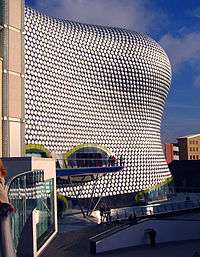

Bullring Shopping Centre was masterplanned and designed mainly by Benoy. The shopping centre consists of two main buildings (East and West Mall) which are connected by an underground passage lined with shops and is also accessible from St Martin's Square via glass doors. The doors to both wings from New Street can be removed when crowds get large and queues develop at the doors. This feature also allows cars for display to be driven into the building. They are sheltered by a glass roof known as the SkyPlane which covers 7,000 square metres (75,000 sq ft) and appears to have no visible means of support.[30] The two malls are different internally in design. The balustrades in the East Mall consist of integrated glass 'jewels' within the metal framework, and are of different colours formed through polyester powder coating.[31] Touchscreen computers, developed by Calm Digital,[32] are located throughout the building which allow a user to search for the location of a certain store or browse a map of the complex. It features a dramatic landmark building, housing a branch of Selfridges department store to a design by the Future Systems architectural practice. The store is clad in 15,000 shiny aluminium discs[33] and was inspired by a Paco Rabanne sequinned dress.[34][35] The Selfridges store cost £60 million and the contractor was Laing O'Rourke. Covering an area of 25,000 square metres (270,000 sq ft), the designs for the Selfridges store were first unveiled in 1999,[33] not long before demolition of the original shopping centre began. The Selfridges store has won eight awards including the RIBA Award for Architecture 2004 and Destination of the Year Retail Week Awards 2004.[36]

There is a multi-storey car park opposite Selfridges on Park Street which is connected to the Selfridges store via a 37-metre long, curved, polycarbonate-covered footbridge,[34][35] known as the Parametric Bridge,[37] suspended over the street. On the ground floor of the car park there is retail space which was previously a furniture showroom.

In 2005, a small Costa Coffee café, designed by Marks Barfield Architects and dubbed the Spiral Café, was constructed alongside the steps leading towards to New Street from St Martin's Square. The building's shape resembled that of shell and featured a curved bronze roof with both ends covered with glass. The main contractors were Thomas Vale and the structural engineers were Price & Myers.[38] The building form is inspired by the mathematician Leonardo Fibonacci who identified natural patterns of growth found throughout the universe, from the shapes of shells and pines cones to fractal patterns within galaxies.[39] The café was knocked down as part of the Spiceal Street redevelopment in 2011.

The entire redevelopment was accompanied by an official project magazine and then commemorated with an 'art book' style book which covered Bullring's transformation in illustration and photography. Both book and magazine were produced by specialist publisher Alma Media International on behalf of the developers.[40]

The shopping centre's design has both its admirers and detractors. In 2008, a poll conducted in conjunction with SimCity Creator stated that Bullring was the ugliest building in the country,[41] although the poll has been criticised.[42]

Spiceal Street

On 6 September 2010, plans were announced for a 20,000 sq ft (1,900 m2) expansion with the creation of three new restaurant units totalling around 10,000 sq ft (930 m2) in St Martins Square with the existing Pizza Hut and Nandos to be extended out closer to St Martins Church and thus expanded. The new restaurants are 'Browns Bar & Brasserie' and 'Chaobaby', opening their first restaurants in Birmingham in the larger two of the units closest to Jamies Italian. The third unit, closest to Selfridges is home to 'Handmade Burger Co'. In addition to the existing Nandos, Wagamama, Pizza Hut, Jamie's Italian and 'Mount Fuiji'. this has created a hub of seven restaurants named after the traditional Spiceal Street. Construction of the part indoor, part outdoor development commenced in March 2011 and consists of a glass, wooden and aluminium exterior and "ribbon" effect roof. The award winning Spiral Cafe that was once sited here has been relocated off-site. The new Spiceal Street opened on 24 November 2011[43]

Artwork

Numerous pieces of artwork are located in the grounds of the centre:[44]

- A 120-square-metre (1,290 sq ft) glass mural by artist Martin Donlin faces the entrance to Birmingham New Street station.

- Three light wands of varying height stand in Rotunda square near the entrances to both wings of Bullring. The wands sway in the wind and reflective platforms which protrude from the main carbon fibre core reflect light to create a beacon effect. At night the cores are illuminated in the colours of the shafts which are blue, green and red.

- At the main entrance to the west building stands The Guardian, a 2.2-metre (7 ft 3 in) tall bronze sculpture of a running, turning bull. It was created by Laurence Broderick[45] and has become a very popular photographic feature for visitors to Birmingham. The statue was vandalised in 2005,[46] requiring that it be removed for repairs, but was returned to its spot again later that year. The sculptor gave support to calls for the statue to be renamed "Brummie the Bull". However, it is more widely known as simply "The Bull."[47] The sculpture was vandalised again in 2006.[48]

- Looking over St Martin's Square is the statue of Horatio Nelson. The bronze statue was the first public monument for Birmingham and was sculpted by Richard Westmacott. It is also the first figurative memorial to Lord Nelson to be erected in Great Britain (only second in the world after Montreal) and was unveiled on 25 October 1809, as part of King George III's Golden Jubilee celebrations. It was originally located on the edge of the previous Bull Ring and stood on a marble base, but this was damaged when the statue was moved in 1958 and the current Portland stone plinth dates from 1960. As part of the Bullring development, the developer agreed to restore the statue and railings, but in 2003 when the Bullring opened, there was no sign of the railings. The Birmingham Civic Society mounted a campaign to get the railings re-instated, whilst Bullring argued they were a health and safety risk and would destroy the openness of the public space. However, the railing were re-instated in September 2005 for the bi-centenary celebrations of the Battle of Trafalgar.

- As each Christmas approaches, a silver-coloured structure is erected in St Martin's Square which resembles a stylised Christmas tree. Large chrome balls hang within the conical shaped structure which is adorned in chrome stars. Large 3-dimensional stars hang between both buildings. Both the stars and chrome sculpture are illuminated at night.

- On 4 June 2008, the 'Bullring Britannia', a cruise ship located outside the shopping centre in St Martin's Square, was unveiled by the shopping centre owners. Throughout the summer, events took place aboard the ship including fashion shows, Mr Sexy Legs competition and activities for children.

Rotunda

A part of the James A. Roberts design for the first Bull Ring Shopping Centre included a 12 storey circular office block. However, upon revising his design this was increased to 25 storeys. As a result of this, plans for a rooftop restaurant and a cinema were dropped. This became the Rotunda and is a surviving component of the 1960s development.

The Rotunda has been converted into apartments by developers Urban Splash. Although located close to the development and constructed at the same time as the 1960s centre, it was not part of the development despite being included in the design. A poem is engraved into one of the stones in the wall of the Bullring dedicated to the Rotunda. The public space to the front of both malls facing the High Street and New Street is named Rotunda Square after the building.

Major Stores

Restaurants and cafes

|

Trading levels

In its first year of service, 36.5 million visitors to the new Bullring were recorded, making it the most visited shopping centre outside the West End of London.[49] This exceeded even the most optimistic predictions, and for Bullring's supporters has justified the £530 million cost of building it. The new Bullring is now one of Europe's largest city centre shopping centres.

An advertising campaign operated during the year to attract visitors. The campaign consisted mainly of television advertisements which used the slogan:

| “ | Europe's shopping capital is no longer on the mainland. | ” |

Leaflets were handed to the public so that the managers of the shopping centre could hear of the views of the people who visit it.

References

- ↑ "Bullring Facts". Official Bullring Website. Archived from the original on 23 September 2010.

- ↑

- ↑ "Bullring Birmingham - Bullring Shops | Birmingham Shopping Centre". E-architect.co.uk. Retrieved 4 November 2013.

- ↑ "Letting Area (square metres), 2007" from page 15 of Key Note, Market Assessment 2008: Shopping Centres, ISBN 978-1-84729-231-5

- ↑ "Parking". Bullring.co.uk. Retrieved 4 November 2013.

- 1 2 3 Remaking Birmingham: The Visual Culture of Urban Regeneration. Kennedy, Routledge Ltd. 2004. pp. 17–18. ISBN 0-415-28839-8.

- ↑ "UK's busiest shopping centre". icBirmingham. Retrieved 6 March 2008.

- ↑ Hoge, Warren (4 December 2003). "Britain's No. 2 City Gets Respect (After All These Years)". The New York Times. Retrieved 10 February 2012.

- ↑ John Lerwill. "Birmingham - its history and traditions". John Lerwill. Retrieved 29 May 2008.

- 1 2 3 4 John Morris Jones. "The Centre of Birmingham". Birmingham Grid For Learning. Retrieved 29 May 2008.

- ↑ Rodrick, Anne Baltz (2004). Self-Help and Civic Culture: Citizenship in the Victorian Birmingham. Ashgate Publishing Ltd. p. 65. ISBN 0-7546-3307-1.

- ↑ Morris, Max (1951). From Cobbett to the Chartists, 1815-1848: extracts from contemporary sources. Lawrence & Wishart. p. 151.

- ↑ A History of the County of Warwick: Volume 7: The City of Birmingham (1964), pp. 251-252 'Economic and Social History: Markets and Fairs' Archived 30 August 2014 at the Wayback Machine. British History Online; Date Retrieved 29 May 2008

- ↑ "The Bull Ring - Then and Now: Victorian and Edwardian Days". Birmingham City Council. Archived from the original on 10 May 2008. Retrieved 29 May 2008.

- ↑ Noszlopy, George Thomas (1998). Public Sculpture of Birmingham: Including Sutton Coldfield. Liverpool University Press. p. 160. ISBN 0-85323-692-5.

- ↑ I'VE JUST TWO WORDS FOR IT!; Name change protest - Birmingham Evening Mail, 29 August 2003

- ↑ Ritchie, p. 140

- ↑ Douglas Hickman (1970). Birmingham. Studio Vista Ltd. p. 71.

- ↑ Deckker, Thomas (2000). The Modern City Revisited. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 0-419-25640-7.

- ↑ "Historian says Bullring lacks heart". news.bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 27 February 2013.

- ↑ Hurst, Ben (17 December 2015). "Search launched for missing nine ton Bull Ring bulls". Birmingham Mail. Retrieved 27 December 2015.

- ↑ "Help Find Our Missing Art". Historic England. Retrieved 27 December 2015.

- ↑ Larkham, Peter J. (1996). Conservation and the City. Routledge. p. 56. ISBN 0-415-07947-0.

- ↑ Guy Jackson (19 June 1998). "Red tape means blue-chip store may abandon move to city". The Independent. Retrieved 11 November 2006.

- ↑ "Building the BullRing" (PDF). Birmingham City Council. Retrieved 29 May 2008.

- ↑ "New look for much maligned centre". icBirmingham. 4 September 2003. Retrieved 17 March 2007.

- ↑ "Robert McAlpine Bullring project" Check

|url=value (help). - ↑ "New Bullring Shopping Centre".

- ↑ "276,600 welcome Bullring". icBirmingham. 5 September 2003. Retrieved 17 March 2007.

- ↑ "Bullring, Birmingham, UK". Benoy. Retrieved 29 May 2008.

- ↑ Perfect finish for Bullring balustrades, Finishing, 1 September 2003

- ↑ "Birmingham Bull Ring". Calm Digital. Archived from the original on 13 July 2007.

- 1 2 "Selfridges Birmingham". Future Systems. Retrieved 11 November 2006.

- 1 2 Clark, Ed; Gilpin, David. "Selfridges, Birmingham" (PDF). Arup. Retrieved 29 May 2008.

- 1 2 Clark, Ed; Gilpin, David (2006). "Selfridges, Birmingham" (PDF). The Arup Journal. Arup. Retrieved 4 November 2013. - via Formpig.com.

- ↑ "Future Systems Awards". Future Systems. 2004. Archived from the original on 31 May 2008. Retrieved 11 November 2006.

- ↑ "Parametric Bridge". Spatial Information Architecture Laboratory. Retrieved 29 May 2008.

- ↑ "Copper in Architecture Design Award - Spiral Cafe, St Martin's Square, Birmingham". Copper in Architecture. Retrieved 29 May 2008.

- ↑ "Spiral Café completed". World Architecture News. 18 July 2005. Retrieved 22 December 2007.

- ↑ "BULLRING". Alma Media. Retrieved 29 May 2008.

- ↑ "Birmingham named UK's ugliest city". The Independent. London. 16 October 2008. Retrieved 1 November 2008.

- ↑ Payne, Rich (14 October 2008). "Dubious List Of UK's Ugliest Buildings Released". 4Homes (Channel 4). Retrieved 1 November 2008.

- ↑ "Spiceal Street".

- ↑ "Art of the Bullring". BBC Birmingham. September 2003. Retrieved 29 April 2008.

- ↑ "Sculptor finally given plaque tribute". icBirmingham. 14 September 2004. Retrieved 17 September 2007.

- ↑ "Bully's put out of sight". Birmingham Mail. 29 June 2005. Retrieved 17 March 2007.

- ↑ "Bull's creator backs name campaign". icBirmingham. 6 November 2003. Retrieved 11 November 2006.

- ↑ "Brum's bull in new vandal attack". Birmingham Mail. 6 February 2006. Retrieved 17 March 2007.

- ↑ "UK's busiest shopping centre". icBirmingham. 3 September 2004. Retrieved 17 March 2007.

Sources

- Baird, Patrick (28 April 2004). The Bull Ring, Birmingham. Sutton Publishing. ISBN 0-7509-2920-0.

- Chinn, Carl (2001). Brum and Brummies: Volume 2. Chapter 1: The Heart of Brum: The Bull Ring. ISBN 1-85858-202-4.

- Laing (1960). The Bull Ring Centre. Laing developers.

- Price, Victor J. (1989). The Bull Ring remembered: the heart of Birmingham and market areas. Studley: Brewin.

- Ritchie, Berry (1997). The Good Builder: The John Laing Story. James & James.

- Stephens, W.B. (1964). "The Growth of the City", A History of the County of Warwick: Volume 7: The City of Birmingham.

- Upton, Chris (1993). A History of Birmingham. Chapter 26: The Changing Bull Ring. ISBN 0-85033-870-0.

External links

- Bullring shopping centre

- Birmingham. Bull Ring Centre Opened, 1964 (Pathé newsreel)

- 1890 Ordnance Survey map of the Bull Ring

- Article on the architecture of the new Bull Ring shopping centre