Naraka (Buddhism)

| Naraka | |||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese | 那落迦 | ||||||

| |||||||

| Diyu | |||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 地獄 | ||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 地狱 | ||||||

| |||||||

| Tibetan name | |||||||

| Tibetan | དམྱལ་བ་ | ||||||

| |||||||

| Thai name | |||||||

| Thai | นรก | ||||||

| RTGS | Nárók | ||||||

| Korean name | |||||||

| Hangul | 지옥 | ||||||

| Hanja | 地獄 | ||||||

| |||||||

| Japanese name | |||||||

| Kanji | 地獄 / 奈落 | ||||||

| |||||||

| Malay name | |||||||

| Malay | Neraka | ||||||

| Khmer name | |||||||

| Khmer | នរក ("Nɔrʊək") | ||||||

| Sanskrit name | |||||||

| Sanskrit |

नरक (in Devanagari) Naraka (Romanised) | ||||||

| Pāli name | |||||||

| Pāli |

निरय (in Devanagari) Niraya (Romanised) | ||||||

| Part of a series on |

| Buddhism |

|---|

|

|

Naraka (Sanskrit: नरक; Pali: निरय Niraya) is a term in Buddhist cosmology[1] usually referred to in English as "hell", "hell realm", or "purgatory". The Narakas of Buddhism are closely related to diyu, the hell in Chinese mythology. A Naraka differs from the hell of Christianity in two respects: firstly, beings are not sent to Naraka as the result of a divine judgment and punishment; secondly, the length of a being's stay in a Naraka is not eternal, though it is usually very long.

A being is born into a Naraka as a direct result of his or her accumulated actions (karma) and resides there for a finite period of time until that karma has achieved its full result.[2] After his or her karma is used up, he or she will be reborn in one of the higher worlds as the result of karma that had not yet ripened.

In the Devaduta Sutta, the 130th discourse of Majjhima Nikaya, the Buddha teaches about hell in vivid detail.

Physically, Narakas are thought of as a series of cavernous layers which extend below Jambudvīpa (the ordinary human world) into the earth. There are several schemes for enumerating these Narakas and describing their torments. The Abhidharma-kosa (Treasure House of Higher Knowledge) is the root text that describes the most common scheme, the Eight Cold Narakas and Eight Hot Narakas.[3]

Cold Narakas

- Arbuda (頞部陀), the "blister" Naraka, is a dark, frozen plain surrounded by icy mountains and continually swept by blizzards. Inhabitants of this world arise fully grown and abide lifelong naked and alone, while the cold raises blisters upon their bodies. The length of life in this Naraka is said to be the time it would take to empty a barrel of sesame seed if one only took out a single seed every hundred years.[4]

- Nirarbuda (刺部陀), the "burst blister" Naraka, is even colder than Arbuda. There, the blisters burst open, leaving the beings' bodies covered with frozen blood and pus.[4]

- Aṭaṭa (頞听陀) is the "shivering" Naraka. There, beings shiver in the cold, making an aṭ-aṭ-aṭ sound with their mouths.[4]

- Hahava (臛臛婆;) is the "lamentation" Naraka. There, the beings lament in the cold, going haa, haa in pain.[4]

- Huhuva (虎々婆), the "chattering teeth" Naraka, is where beings shiver as their teeth chatter, making the sound hu, hu.[4]

- Utpala (嗢鉢羅) is the "blue lotus" Naraka. The intense cold there makes the skin turn blue like the colour of an utpala waterlily.[4]

- Padma (鉢特摩), the "lotus" Naraka, has blizzards that cracks open frozen skin, leaving one raw and bloody.

- Mahāpadma (摩訶鉢特摩) is the "great lotus" Naraka. The entire body cracks into pieces and the internal organs are exposed to the cold, also cracking.[4]

Each lifetime in these Narakas is twenty times the length of the one before it.

Hot Narakas

- Sañjīva, the "reviving" Naraka, has ground made of hot iron heated by an immense fire. Beings in this Naraka appear fully grown, already in a state of fear and misery. As soon as the being begins to fear being harmed by others, their fellows appear and attack each other with iron claws and hell guards appear and attack the being with fiery weapons. As soon as the being experiences an unconsciousness like death, they are suddenly restored to full health and the attacks begin again. Other tortures experienced in this Naraka include having molten metal dropped upon them, being sliced into pieces, and suffering from the heat of the iron ground.[4] Life in this Naraka is 1.62×1012 years long.[5] It is said to be 1000 yojanas beneath Jambudvīpa and 10,000 yojanas in each direction (a yojana being 7 miles, or 11 kilometres).[6]

- Kālasūtra, the "black thread" Naraka, includes the torments of Sañjīva. In addition, black lines are drawn upon the body, which hell guards use as guides to cut the beings with fiery saws and sharp axes.[4][6] Life in this Naraka is 1.296×1013 years long.[5]

- Saṃghāta, the "crushing" Naraka, is surrounded by huge masses of rock that smash together and crush the beings to a bloody jelly. When the rocks move apart again, life is restored to the being and the process starts again.[4] Life in this Naraka is 1.0368×1014 years long.[5]

- Raurava, the "screaming" Naraka, is where beings run wildly about, looking for refuge from the burning ground.[4] When they find an apparent shelter, they are locked inside it as it blazes around them, while they scream inside. Life in this Naraka is 8.2944×1014 years long.

- Mahāraurava, the "great screaming" Naraka, is similar to Raurava.[6] Punishment here is for people who maintain their own body by hurting others. In this hell, ruru animals known as kravyāda torment them and eat their flesh. Life in this Naraka is 6.63552×1015 years long.

- Tapana is the "heating" Naraka, where hell guards impale beings on a fiery spear until flames issue from their noses and mouths.[4] Life in this Naraka is 5.308416×1016 years long.

- Pratāpana, the "great heating" Naraka. The tortures here are similar to the Tapana Naraka, but the beings are pierced more bloodily with a trident.[4] Life in this Naraka is 4.2467328×1017 years long. It is also said to last for the length of half an antarakalpa.

- Avīci is the "uninterrupted" Naraka. Beings are roasted in an immense blazing oven with terrible suffering.[4] Life in this Naraka is 3.39738624×1018 years long. It is also said to last for the length of an antarakalpa.

Some sources describe five hundred or even hundreds of thousands of different Narakas.

The sufferings of the dwellers in Naraka often resemble those of the Pretas, and the two types of being are easily confused. The simplest distinction is that beings in Naraka are confined to their subterranean world, while the Pretas are free to move about.

There are also isolated and boundary hells called Pratyeka Narakas (Pali: Pacceka-niraya) and Lokantarikas.

In Buddhist literature

The Dīrghāgama or Longer Āgama-sūtra (Ch. cháng āhán jīng 長阿含經),[7] was translated to Chinese in 22 fascicles from an Indic original by Buddhayaśas (Fotuoyeshe 佛陀耶舍) and Zhu Fonian 竺佛念 in 412–13 CE.[8] This literature contains 30 discrete scriptures in four groups (vargas). The fourth varga, which pertains to Buddhist cosmology,[9] contains a "Chapter on Hell" (dìyù pǐn 地獄品) within the Scripture of the Account of the World (shìjì jīng 世記經). In this text, the Buddha describes to the sangha each of the hells in great detail, beginning with their physical location and names:

佛告比丘:「此四天下有八千天下圍遶其外。復有大海水周匝圍遶八千天下。復有大金剛山遶大海水。金剛山外復有第二大金剛山。二山中間窈窈冥冥。日月神天有大威力。不能以光照及於彼。彼有八大地獄。其一地獄有十六小地獄。第一大地獄名想。第二名黑繩。第三名堆壓。第四名叫喚。第五名大叫喚。第六名燒炙。第七名大燒炙。第八名無間。其想地獄有十六小獄。小獄縱廣五百由旬。第一小獄名曰黑沙。二名沸屎。三名五百丁。四名飢。五名渴。六名一銅釜。七名多銅釜。八名石磨。九名膿血。十名量火。十一名灰河。十二名鐵丸。十三名釿斧。十四名犲狼。十五名劍樹。十六名寒氷。[10]

The Buddha told the bhikṣus, "There are 8,000 continents surrounding the four continents [on earth]. There is, moreover, a great sea surrounding those 8,000 continents. There is, moreover, a great diamond mountain range encircling that great sea. Beyond this great diamond mountain range is yet another great diamond mountain range. And between the two mountain ranges lies darkness. The sun and moon in the divine sky with their great power are unable to reach that [darkness] with their light. In [that space between the two diamond mountain ranges] there are eight major hells. Along with each major hell are sixteen smaller hells.

"The first major hell is called Thoughts. The second is called Black Rope. The third is called Crushing. The fourth is called Moaning. The fifth is called Great Moaning. The sixth is called Burning. The seventh is called Great Burning. The eighth is called Unremitting. The Hell of Thoughts contains sixteen smaller hells. The smaller hells are 500 square yojana in area. The first small hell is called Black Sand. The second hell is called Boiling Excrement. The third is called Five Hundred Nails. The fourth is called Hunger. The fifth is called Thirst. The sixth is called Single Copper Cauldron. The seventh is called Many Copper Cauldrons. The eighth is called Stone Pestle. The ninth is called Pus and Blood. The tenth is called Measuring Fire. The eleventh is called Ash River. The twelfth is called Iron Pellets. The thirteenth is called Axes and Hatchets. The fourteenth is called Jackals and Wolves. The fifteenth is called Sword Cuts. The sixteenth is called Cold and Ice.""

Further evidence supporting the importance of these texts discussing hells lies in Buddhists' further investigation of the nature of hell and its denizens. Buddhavarman's fifth century Chinese translation of the Abhidharma-vibhāṣā-śāstra (Ch. āpídámó pípóshā lùn 阿毘曇毘婆沙論) questions whether hell wardens who torture hell beings are themselves sentient beings, what form they take, and what language they speak.[11] Xuanzang's 玄奘 seventh century Chinese translation of the Abhidharmakośa śāstra (Ch. āpídámó jùshè lùn 阿毘達磨倶舍論) too is concerned with whether hell wardens are sentient beings, as well as how they go on to receive karmic retribution, whether they create bad karma at all, and why are they not physically affected and burned by the fires of hell.[12]

Descriptions of the Narakas are a common subject in some forms of Buddhist commentary and popular literature as cautionary tales against the fate that befalls evildoers and an encouragement to virtue.[13]

The Mahāyāna Sūtra of the bodhisattva Kṣitigarbha (Dìzàng or Jizō) graphically describes the sufferings in Naraka and explains how ordinary people can transfer merit in order to relieve the sufferings of the beings there.

The Japanese monk Genshin began his Ōjōyōshū with a description of the suffering in Naraka. Tibetan Lamrim texts also included a similar description.

Chinese Buddhist texts considerably enlarged upon the description of Naraka (Diyu), detailing additional Narakas and their punishments, and expanding the role of Yama and his helpers, Ox-Head and Horse-Face. In these texts, Naraka became an integral part of the otherworldly bureaucracy which mirrored the imperial Chinese administration.

Gallery

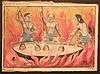

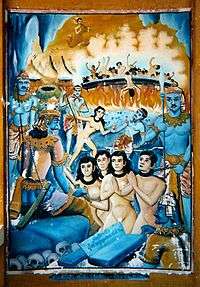

A mural from a temple in northern Thailand depicting naked beings climbing thorn-covered trees, pecked by birds from above, and attacked from below by hell guards armed with spears. There are icy mountains in the background, and Phra Malaya watches from above. |

A mural from a temple in northern Thailand. Human-animal figures are dismembered and disemboweled by hell guards and birds, while Phra Malaya watches from above. |

A mural from a temple in northern Thailand. The unclothed spirits of the dead are brought before Yama for judgement. Phra Malaya watches from above as beings are fried in a large oil cauldron. |

_in_Burmese_art.jpg) shri vishnu dev. Hell guards throw beings into a cauldron and fry them in oil. |

See also

- Bon Festival

- Diyu

- Ghost Festival

- Hell money

- Ksitigarbha

- Maudgalyayana

- Ox-Head and Horse-Face

- Ullambana Sutra

- Yama (East Asia)

Notes

- ↑ Thakur, Upendra (1992). India and Japan, a Study in Interaction During 5th Cent. – 14th Cent. A.D. Abhinav Publications. ISBN 8170172896.

- ↑ Braarvig, Jens (2009). "The Buddhist Hell: An Early Instance of the Idea?". Numen. 56 (2-3): 254. JSTOR 27793792. – via JSTOR (subscription required)

- ↑ Buswell, Robert E. (2003). The Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism. Princeton: Princeton University Press. p. 86.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Alexander, Jane (2009). The Body, Mind, Spirit Miscellany: The Ultimate Collection of Fascinations, Facts, Truths, and Insights. London: Duncan Baird Publishers. pp. 150–151. ISBN 9781844838370.

- 1 2 3 Malik, Akhtar (2007). Survey of Buddhist Temples and Monasteries. New Delhi: Anmol Publications. p. 50. ISBN 9788126132591.

- 1 2 3 Morgan, Diane (2010). Essential Buddhism: A Comprehensive Guide to Belief and Practice. Santa Barbara, California: Praeger. p. 73. ISBN 9780313384523.

- ↑ Taisho vol. 1, no. 1, 1a–149c

- ↑ "長阿含經," Digital Dictionary of Buddhism, www.buddhism-dict.net/cgi-bin/xpr-ddb.pl?q=長阿含經, accessed 5 May 2014 (can be accessed by logging in with username "guest" and leaving password blank)

- ↑ "長阿含經," Digital Dictionary of Buddhism, www.buddhism-dict.net/cgi-bin/xpr-ddb.pl?q=長阿含經

- ↑ T1, no. 1, p. 121, b29-c13

- ↑ 《阿毘曇毘婆沙論》卷7〈2 智品〉Abhidharma-vibhāṣā-śāstra, fascicle 7, "Chapter on Wisdom," T28, no. 1546, p. 48, a5-25

- ↑ 《阿毘達磨俱舍論》卷11〈3 分別世品〉Abhidharmakośa śāstra, fascicle 11, "Chapter on Discerning the World," T1558, no. 29, p. 1–160

- ↑ 诸经佛说地狱集要 (in Chinese).

Further reading

- Matsunaga, Alicia; Matsunaga, Daigan (1971). The Buddhist concept of hell. New York: Philosophical Library.

- Teiser, Stephen F. (1988). "Having Once Died and Returned to Life": Representations of Hell in Medieval China". Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies. 48 (2): 433–464.

- Law, Bimala Churn; Barua, Beni Madhab (1973). Heaven and hell in Buddhist perspective. Varanasi: Bhartiya Pub. House.

External links

- http://www.khandro.net/doctrine_hells.htm

- http://vedabase.net/sb/3/30/25/en

- http://srimadbhagavatam.org/canto5/chapter26.html

- The Thirty-one Planes of Existence

- The Asian Classics Institute course on Death and the Realms of Existence