Brachyury

| View/Edit Human | View/Edit Mouse |

Brachyury is a protein that in humans is encoded by the T gene.[3][4] Brachyury is a transcription factor within the T-box complex of genes.[5] It has been found in all bilaterian animals that have been screened, and is also present in the cnidaria.[5]

History

The brachyury mutation was first described in mice by Nadezhda Alexandrovna Dobrovolskaya-Zavadskaya in 1927 as a mutation that affected tail length and sacral vertebrae in heterozygous animals. In homozygous animals the brachyury mutation is lethal at around embryonic day 10 due to defects in mesoderm formation, notochord differentiation and the absence of structures posterior to the forlimb bud (Dobrovolskaïa-Zavadskaïa, 1927). The name brachyury comes from the Greek brakhus meaning short and oura meaning tail.

According to human and mouse genome nomenclature, brachyury now has the symbol and gene name T although brachyury is maintained as the gene description.

The mouse T gene was cloned by Bernhard Herrmann and colleagues[6] and proved to encode an 436 amino acid embryonic nuclear transcription factor. T binds to a specific DNA element, a near palindromic sequence TCACACCT through a region in its N-terminus, called the T-box. T is the founding member of the T-box family which in mammals currently consists of 18 T-box genes.

Function

The gene brachyury appears to have a conserved role in defining the midline of a bilaterian organism,[7] and thus the establishment of the anterior-posterior axis; this function is apparent in chordates and molluscs.[8] Its ancestral role, or at least the role it plays in the Cnidaria, appears to be in defining the blastopore.[5] It also defines the mesoderm during gastrulation.[9] Tissue-culture based techniques have demonstrated one of its roles may be in controlling the velocity of cells as they leave the primitive streak.[10][11]

Transcription of genes required for mesoderm formation and cellular differentiation.

Brachyury has also been shown to help establish the cervical vertebral blueprint during fetal development. The number of cervical vertebrae is highly conserved among all mammals; however a spontaneous vertebral and spinal dysplasia (VSD) mutation in this gene has been associated with the development of six or fewer cervical vertebrae instead of the usual seven.[12]

Expression

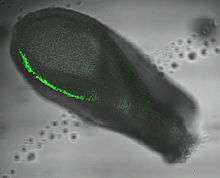

In mice T is expressed in the inner cell mass of the blastocyst stage embryo (but not in the majority of mouse embryonic stem cells) followed by the primitive streak (see image). In later development expression is localised to the node and notochord.

In Xenopus laevis Xbra (the Xenopus T homologue, also recently renamed t) is expressed in the mesodermal marginal zone of the pre-gastrula embryo followed by localisation to the blastopore and notochord at the mid-gastrula stage.

The Danio rerio homologue is known as ntl (no tail)

Cancer

Expression of the brachyury gene has been identified as a definitive diagnostic marker of chordoma, a malignant tumor that arises from remnant notochordal cells lodged in the vertebrae.[13] Furthermore, germ line duplication of brachyury confers major susceptibility to chordoma. The chromosomal region on 6q27 containing the brachyury gene was gained in 6 of 21 chordomas (29%), and none of the 21 chordomas analyzed showed deletions that could have affected this gene.

Brachyury is an important factor in promoting the epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT). Cells that over-express brachyury have down-regulated expression of the adhesion molecule E-cadherin, which allows them to undergo EMT. This process is at least partially mediated by the transcription factors AKT[14] and Snail.[15]

Overexpression of brachyury has been linked to Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC, also called malignant hepatoma), a common type of liver cancer. While brachyury is promoting EMT, it can also induce metastasis of HCC cells. Brachyury expression is a prognostic biomarker for HCC, and the gene may be a target for cancer treatments in the future.[14]

Additionally, overexpression of brachyury may play a part in EMT associated with benign disease such as renal fibrosis.[15]

Brachyury is overexpressed in a number of tumor types.

See also

References

- ↑ "Human PubMed Reference:".

- ↑ "Mouse PubMed Reference:".

- ↑ "Entrez Gene: T".

- ↑ Edwards YH, Putt W, Lekoape KM, Stott D, Fox M, Hopkinson DA, Sowden J (March 1996). "The human homolog T of the mouse T(Brachyury) gene; gene structure, cDNA sequence, and assignment to chromosome 6q27". Genome Res. 6 (3): 226–33. doi:10.1101/gr.6.3.226. PMID 8963900.

- 1 2 3 Scholz CB, Technau U (January 2003). "The ancestral role of Brachyury: expression of NemBra1 in the basal cnidarian Nematostella vectensis (Anthozoa)". Dev. Genes Evol. 212 (12): 563–70. doi:10.1007/s00427-002-0272-x. PMID 12536320.

- ↑ Herrmann BG, Labeit S, Poustka A, King TR, Lehrach H (February 1990). "Cloning of the T gene required in mesoderm formation in the mouse". Nature. 343 (6259): 617–22. doi:10.1038/343617a0. PMID 2154694.

- ↑ Le Gouar, M.; Guillou, A.; Vervoort, M. (2004). "Expression of a SoxB and a Wnt2/13 gene during the development of the mollusc Patella vulgata.". Development genes and evolution. 214 (5): 250–256. doi:10.1007/s00427-004-0399-z. PMID 15034714.

- ↑ Lartillot, N; Lespinet, O; Vervoort, M; Adoutte, A (2002). "Expression pattern of Brachyury in the mollusc Patella vulgata suggests a conserved role in the establishment of the AP axis in Bilateria.". Development. 129 (6): 1411–1421. PMID 11880350.

- ↑ Marcellini, S.; Technau, U.; Smith, J.; Lemaire, P. (2003). "Evolution of Brachyury proteins: identification of a novel regulatory domain conserved within Bilateria". Developmental Biology. 260 (2): 352–361. doi:10.1016/S0012-1606(03)00244-6. PMID 12921737.

- ↑ Hashimoto, K.; Fujimoto, H.; Nakatsuji, N. (1987-08-01). "An ECM substratum allows mouse mesodermal cells isolated from the primitive streak to exhibit motility similar to that inside the embryo and reveals a deficiency in the T/T mutant cells". Development. 100 (4): 587–598. ISSN 0950-1991. PMID 3327671.

- ↑ Turner, David A; Rué, Pau; Mackenzie, Jonathan P; Davies, Eleanor; Arias, Alfonso Martinez (2014-08-13). "Brachyury cooperates with Wnt/β-catenin signalling to elicit primitive-streak-like behaviour in differentiating mouse embryonic stem cells". BMC Biology. 12 (1). doi:10.1186/s12915-014-0063-7. PMC 4171571

. PMID 25115237.

. PMID 25115237. - ↑ Kromik A, Ulrich R, Kusenda M, et al. The mammalian cervical vertebrae blueprint depends on the T (brachyury) Gene. Genetics. 2015;199(3):183+. doi:10.1534/genetics.114.169680.

- ↑ Vujovic S, Henderson S, Presneau N, Odell E, Jacques TS, Tirabosco R, Boshoff C, Flanagan AM (June 2006). "Brachyury, a crucial regulator of notochordal development, is a novel biomarker for chordomas". J. Pathol. 209 (2): 157–65. doi:10.1002/path.1969. PMID 16538613.

- 1 2 Du R, Wu S, Lv H, et al. Overexpression of brachyury contributes to tumor metastasis by inducing epithelial-mesenchymal transition in hepatocellular carcinoma. J Exp Clin Canc Res. 2014;33:105. doi: 10.1186/s13046-014-0105-6.

- 1 2 Sun SR, Sun WJ, Xia L, et al. The T-box transcription factor Brachyury promotes renal interstitial fibrosis by repressing E-cadherin expression. J Cell Commun Signal. 2014; 12:76. doi:10.1186/s12964-014-0076-4.

Further reading

- Yoshikawa T, Piao Y, Zhong J, Matoba R, Carter MG, Wang Y, Goldberg I, Ko MS (January 2006). "High-throughput screen for genes predominantly expressed in the ICM of mouse blastocysts by whole mount in situ hybridization". Gene Expr. Patterns. 6 (2): 213–24. doi:10.1016/j.modgep.2005.06.003. PMC 1850761

. PMID 16325481.

. PMID 16325481. - Meisler (1997). "Mutation watch: Mouse brachyury (T), the T-box gene family, and human disease." (PDF).

External links

- Mouse Genome Informatics entry for T

- European Bioinformatics Institute InterPro entry for Brachyury

- Information Hyperlinked Over Proteins entry for Brachyury

- Xenbase Gene entry for t