Neutron capture therapy of cancer

| Science with Neutrons |

|---|

|

| Foundations |

| Neutron scattering |

| Other applications |

|

| Infrastructure |

|

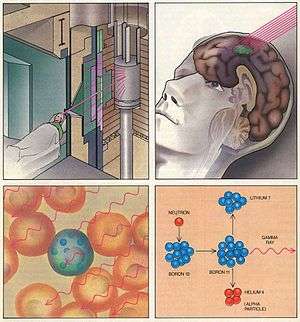

| Neutron facilities |

Neutron capture therapy (NCT) is a noninvasive therapeutic modality for treating locally invasive malignant tumors such as primary brain tumors and recurrent head and neck cancer. It is a two step procedure: first, the patient is injected with a tumor localizing drug containing a non-radioactive isotope that has a high propensity or cross section (σ) to capture slow neutrons. The cross section of the capture agent is many times greater than that of the other elements present in tissues such as hydrogen, oxygen, and nitrogen. In the second step, the patient is radiated with epithermal neutrons, which after losing energy as they penetrate tissue, are absorbed by the capture agent, which subsequently emits high-energy charged particles, thereby resulting in a biologically destructive nuclear reaction (Fig.1).

All of the clinical experience to date with NCT is with the non-radioactive isotope boron-10, and this is known as boron neutron capture therapy (BNCT).[2] At this time, the use of other non-radioactive isotopes, such as gadolinium, has been limited, and to date, it has not been used clinically. BNCT has been evaluated clinically as an alternative to conventional radiation therapy for the treatment of malignant brain tumors (gliomas), and more recently, recurrent, locally advanced head and neck cancer.[3]

Boron neutron capture therapy

History

After the initial discovery of the neutron in 1932 by Sir James Chadwick, H. J. Taylor in 1935 showed that boron-10 nuclei could avidly capture thermal neutrons. This resulted in Nuclear fission of the resulting boron-11 nuclei into helium-4 (alpha particles) and lithium-7 ions. In 1936, G.L. Locher, a scientist at the Franklin Institute in Pennsylvania, recognized the therapeutic potential of this discovery and suggested that neutron capture could be used to treat cancer. W. H. Sweet, from Massachusetts General Hospital, first suggested the technique for the most malignant brain tumors in 1951,[4] and a trial of the therapy against glioblastoma multiforme using borax as the delivery agent was initiated in a collaboration between Brookhaven National Laboratory in Long Island, U.S.A. and the Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston in 1954.[5]

In the current era, a number of research groups throughout the world have continued the early groundbreaking work of Sweet and Fairchild. In particular, a research group headed up by Zamenhof at Harvard and MIT were the first group to use an epithermal neutron beam for clinical trials. The research initially involved patients with cutaneous melanoma and then expanded to patients with cerebral tumors, specifically melanoma metastases and primary glioblastoma multiforme. This Harvard-MIT research group was headed up by the PI Dr. Robert Zamenhof, a medical physicist at Harvard, and included among the research management team, Dr. Otto Harling at MIT and Dr. Paul Busse (the clinical PI) at Harvard's Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston. A total of 23 patients were treated by the Harvard-MIT research group. The initial 5 cutaneous melanoma cases were treated with the initially constructed epithermal neutron beam at the MIT research reactor (MITR-II), while the subsequent brain tumor patients were treated using a redesigned beam at the MIT reactor which possessed far superior characteristics to the original MITR-II beam. All patients were treated with the agent l-p-BPA. These clinical studies were done under sponsorship of the U.S. Department of Energy and the U.S. National Cancer Institute. The clinical outcome of the cases treated at Harvard-MIT was summarized by Busse (ref) and Palmer (ref). The overall conclusion of these studies was highly encouraging. Unfortunately, the departure of Dr. Busse from the program and the lack of identification of a replacement clinical PI by Dr. Busse resulted in the closure of the Harvard-MIT NCT program in 2003.

Clinical NCT programs continued for a few years thereafter in Sweden, Finland, Czech Republic, Argentina, European Union (centered in the Netherlands) and Japan. Currently, only the program in Japan continues to treat patients.

Basic principles

Neutron capture therapy is a binary system that uses two separate components to achieve a therapeutic effect. Each component in itself is non-tumoricidal, but when combined together they are highly lethal to cancer cells.

_illustration.jpg)

Boron neutron capture therapy (BNCT) is based on the nuclear capture and fission reactions that occur when non-radioactive boron-10, which makes up approximately 20% of natural elemental boron, is irradiated with neutrons of the appropriate energy to yield excited boron-11 (11B*), which in turn decays into high energy alpha particles (4He nuclei) and high energy lithium-7 (7Li) nuclei. The nuclear reaction is:

- 10B + nth → [11B] *→ α + 7Li + 2.31 MeV

Both the alpha particles and the lithium ions produce closely spaced ionizations in the immediate vicinity of the reaction, with a range of approximately 5–9 µm, the diameter of the target cell. The lethality of the capture reaction is limited to boron containing cells. BNCT, therefore, can be regarded as both a biologically and a physically targeted type of radiation therapy. The success of BNCT is dependent upon the selective delivery of sufficient amounts of 10B to the tumor with only small amounts localized in the surrounding normal tissues.[6] Thus, normal tissues, if they have not taken up sufficient amounts of boron-10, can be spared from the nuclear capture and fission reactions. Normal tissue tolerance is determined by the nuclear capture reactions that occur with normal tissue hydrogen and nitrogen.

A wide variety of boron delivery agents have been synthesized,[7] but only two of these currently are being used in clinical trials. The first, which has been used primarily in Japan, is a polyhedral borane anion, sodium borocaptate or BSH (Na2B12H11SH), and the second is a dihydroxyboryl derivative of phenylalanine, referred to as boronophenylalanine or BPA. The latter has been used in clinical trials in the United States, Europe, Japan and more recently, Argentina and Taiwan. Following administration of either BPA or BSH by intravenous infusion, the tumor site is irradiated with neutrons, the source of which has been specially modified nuclear reactors. Up to 1994, low-energy (< 0.5 eV) thermal neutron beams were used primarily in Japan,[8] but since they have a limited depth of penetration in tissues, higher energy (>.5eV<10 keV) epithermal neutron beams, which have a greater depth of penetration, have been used in clinical trials in the United States,[9][10] Europe,[11][12] and Japan.[13][14]

In theory BNCT is a highly selective type of radiation therapy that can target tumor cells without causing radiation damage to the adjacent normal cells and tissues. Doses up to 60–70 Gy can be delivered to the tumor cells in one or two applications compared to 6–7 weeks for conventional external beam photon irradiation. However, the effectiveness of BNCT is dependent upon a relatively homogeneous distribution of 10B within the tumor, and this is still one of the main unsolved problems that have limited its success.

Radiobiological considerations

The radiation doses delivered to tumor and normal tissues during BNCT are due to energy deposition from three types of directly ionizing radiation that differ in their linear energy transfer (LET), which is the rate of energy loss along the path of an ionizing particle:

1. low LET gamma rays, resulting primarily from the capture of thermal neutrons by normal tissue hydrogen atoms [1H(n,γ)2H];

2. high LET protons, produced by the scattering of fast neutrons and from the capture of thermal neutrons by nitrogen atoms [14N(n,p)14C]; and

3. high LET, heavier charged alpha particles (stripped down 4He nuclei) and lithium-7 ions, released as products of the thermal neutron capture and fission reactions with 10B [10B(n,α)7Li].

Since both tumor and surrounding normal tissues are present in the radiation field, even with an ideal epithermal neutron beam, there will be an unavoidable, nonspecific background dose, consisting of both high and low LET radiation. However, a higher concentration of 10B in the tumor will result in it receiving a higher total dose than that of adjacent normal tissues, which is the basis for the therapeutic gain in BNCT.[15] The total radiation dose (Gy) delivered to any tissue can be expressed in photon-equivalent units as the sum of each of the high LET dose components multiplied by weighting factors (Gyw), which depend on the increased radiobiological effectiveness of each of these components.

Clinical dosimetry

Biological weighting factors have been used in all of the recent clinical trials in patients with high grade gliomas, using boronophenylalanine (BPA) in combination with an epithermal neutron beam. The 10B(n,α)7Li component of the radiation dose to the scalp has been based on the measured boron concentration in the blood at the time of BNCT, assuming a blood: scalp boron concentration ratio of 1.5:1 and a compound biological effectiveness (CBE) factor for BPA in skin of 2.5. A relative biological effectiveness (RBE) factor of 3.2 has been used in all tissues for the high LET components of the beam, such as alpha particles. The RBE factor is used to compare the biologic effectiveness of different types of ionizing radiation. The high LET components include protons resulting from the capture reaction with normal tissue nitrogen, and recoil protons resulting from the collision of fast neutrons with hydrogen.[15] It must be emphasized that the tissue distribution of the boron delivery agent in humans should be similar to that in the experimental animal model in order to use the experimentally derived values for estimation of the radiation doses for clinical radiations.[15] For more detailed information relating to computational dosimetry and treatment planning, interested readers are referred to a comprehensive review on this subject.[16]

Boron delivery agents

The development of boron delivery agents for BNCT began approximately 50 years ago and is an ongoing and difficult task of high priority. A number of boron-10 containing delivery agents have been prepared for potential use in BNCT.[7][17] The most important requirements for a successful boron delivery agent are:

- low systemic toxicity and normal tissue uptake with high tumor uptake and concomitantly high tumor: to brain (T:Br) and tumor: to blood (T:Bl) concentration ratios (> 3–4:1);

- tumor concentrations in the range of ~20 µg 10B/g tumor;

- rapid clearance from blood and normal tissues and persistence in tumor during BNCT.

However, it should be noted that at this time no single boron delivery agent fulfills all of these criteria. With the development of new chemical synthetic techniques and increased knowledge of the biological and biochemical requirements needed for an effective agent and their modes of delivery, a number of promising new boron agents has emerged (see examples in Table 1).

| *Boronophenylalanine ("BPA") | *Sodium borocaptate ("BSH") |

| Dodecaborate cluster lipids and cholesterol derivatives | Carboranyl nucleosides |

| "GB10" (Na2B10H10) | Carboranyl porphyrins |

| Cholesteryl ester mimics | Boronated EGF and anti-EGFR mAbs |

| Boronated DNA metallo-intercalators | Boron-containing nanoparticles |

| Transferrin–polyethylene glycol (TF–PEG) liposomes | Carboranyl porphrazines |

| Unnatural amino acids | Boronated cyclic peptides |

| Dodecahydro-closo-dodecaborate clusters | Boron carbide particles |

*These are the only two boron delivery agents that have been used clinically.

The major challenge in the development of boron delivery agents has been the requirement for selective tumor targeting in order to achieve boron concentrations sufficient to produce therapeutic doses of radiation at the site of the tumor with minimal radiation delivered to normal tissues. The selective destruction of brain tumor (glioma) cells in the presence of normal cells represents an even greater challenge compared to malignancies at other sites in the body, since malignant gliomas are highly infiltrative of normal brain, histologically diverse and heterogeneous in their genomic profile. In principle, NCT is a radiation therapy that could selectively deliver lethal doses of radiation to tumor cells while sparing adjacent normal cells.

Gadolinium neutron capture therapy (Gd NCT)

There also has been interest in the possible use of gadolinium-157 (157Gd) as a capture agent for NCT for the following reasons:[18] First, and foremost, has been its very high neutron capture cross section of 254,000 barns. Second, gadolinium compounds, such as Gd-DTPA (gadopentetate dimeglumine Magnevist®), have been used routinely as contrast agents for magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of brain tumors and have shown high uptake by brain tumor cells in tissue culture (in vitro).[19] Third, gamma rays and internal conversion and Auger electrons are products of the 157Gd (n,γ)158Gd capture reaction (157Gd + nth (0.025eV) → [158Gd] → 158Gd + γ + 7.94 MeV).

Although the gamma rays have long pathlengths, orders of magnitude greater depths of penetration compared with the other radiations, the other radiation products (internal conversion and Auger electrons) have pathlengths of approximately one cell diameter and can directly damage DNA. Therefore, it would be highly advantageous for the production of DNA damage if the 157Gd were localized within the cell nucleus. However, the possibility of incorporating gadolinium into biologically active molecules is very limited and only a small number of potential delivery agents for Gd NCT have been studied.[20][21]

Relatively few studies with Gd have been carried out in experimental animals compared to the large number with boron containing compounds (Table 1), which have been synthesized and evaluated in experimental animals (in vivo). Although in vitro activity has been demonstrated using the Gd-containing MRI contrast agent Magnevist® as the Gd delivery agent,[22] there are very few studies demonstrating the efficacy of Gd NCT in experimental animal tumor models,[21][23] and Gd NCT has to date never been used clinically (i.e., in humans).

Neutron sources

Nuclear reactors

Neutron sources for NCT have been limited to nuclear reactors and in the present section we only will summarize information that is described in more detail in a recently published review.[24] Reactor derived neutrons are classified according to their energies as thermal (En <0.5 eV), epithermal (0.5 eV <En <10 keV) or fast (En >10 keV). Thermal neutrons are the most important for BNCT since they usually initiate the 10B(n,α)7Li capture reaction. However, because they have a limited depth of penetration, epithermal neutrons, which lose energy and fall into the thermal range as they penetrate tissues, are now preferred for clinical therapy.

A number of nuclear reactors with very good neutron beam quality have been developed and used clinically. These include:

- Kyoto University Research Reactor (KURR) in Kumatori, Japan;

- the Massachusetts Institute of Technology Research Reactor (MITR);

- the RA-6 CNEA reactor in Bariloche, Argentina;

- the High Flux Reactor (HFR) at Petten in the Netherlands; and

- the FiR1 (Triga Mk II) research reactor at VTT Technical Research Centre, Espoo, Finland.

Although not currently being used for BNCT, the neutron irradiation facility at the MITR represented the state of the art in epithermal beams for NCT with the capability of completing a radiation field in 10–15 minutes with close to the theoretically maximum ratio of tumor to normal tissue dose. Unfortunately, however, no clinical studies currently are being carried out at the HFR and the MITR. The operation of the BNCT facility at the Finnish FiR1 research reactor (Triga Mk II), treating patients since 1999, was terminated in 2012 due to financial reasons and the fate of this BNCT facility is uncertain at this time. Finally, a low power "in-hospital" compact nuclear reactor has been designed and built in Beijing, China, and at this time has only been used on an experimental basis to treat a very small number of patients with cutaneous melanomas.[25]

Accelerators

Accelerators also can be used to produce epithermal neutrons and accelerator-based neutron sources (ABNS) are being developed in a number of countries. Interested readers are referred to the recently published Proceedings of the 15th and 16th International Congresses[26][27] on Neutron Capture Therapy for more information on this subject. For ABNSs, one of the more promising nuclear reactions involves bombarding a 7Li target with high energy protons. An experimental BNCT facility, using a thick lithium solid target, has been in use since the early 1990s at the University of Birmingham in the UK, but to date no clinical studies have been carried out at this facility, which makes use of a high current Dynamitron accelerator originally supplied by Radiation Dynamics.

Recently, a prototypic cyclotron-based neutron source (C-BENS) has been developed by Sumitomo Heavy Industries in Japan.[28] It has been installed at the Particle Radiation Oncology Research Center of Kyoto University in Japan. It now is being used in a Phase I clinical trial to evaluate its safety for treating patients with high grade gliomas. A second one has been constructed by Mitsubishi Heavy Industries for use at Tsukuba University in Japan, and should be ready for clinical use in 2016. A third one is being built by Hitachi for use in Tokyo and a fourth one is undergoing evaluation in Sendai, Japan. Finally, a fifth one is in the developmental stage and would utilize an accelerator fabricated by GT Advanced Technologies in Danvers, Massachusetts. This one will have a liquid lithium-7 target, designed by Osaka University, and it will be evaluated by a consortium of institutions, including Osaka University, as a demonstration project. Once clinical trials have been initiated, it will be important to determine how these ABNS compare to BNCT that has been carried out in the past using nuclear reactors as the neutron source.

Clinical studies of BNCT for brain tumors

Early studies in the US and Japan

It was not until the 1950s that the first clinical trials were initiated by Farr at the Brookhaven National Laboratory (BNL) in New York[5] and by Sweet and Brownell at the Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) using the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) nuclear reactor (MITR)[29] and several different low molecular weight boron compounds as the boron containing drug. However, the results of these studies were disappointing, and no further clinical trials were carried out in the United States until the 1990s.

Following a two-year fellowship in Sweet's laboratory, clinical studies were initiated by Hiroshi Hatanaka in Japan in 1967. He used a low energy thermal neutron beam, which has low tissue penetrating properties and sodium borocaptate (BSH) as the boron delivery agent. Initially, this had been developed as a boron delivery agent by Albert Soloway at the MGH.[30] In Hatanaka's procedure,[31] as much as possible of the tumor was surgically resected ("debulking"), and at some time thereafter, BSH was administered by a slow infusion, usually intra-arterially, but later intravenously. Twelve to 14 hours later, BNCT was carried out at one or another of several different nuclear reactors using low energy thermal neutron beams. The less tissue-penetrating properties of the thermal neutron beams necessitated reflecting the skin and raising a bone flap in order to directly irradiate the exposed brain, a procedure first used by Sweet and his collaborators.

Approximately 200+ patients were treated by Hatanaka, and subsequently by his associate, Nakagawa.[8] Due to the heterogeneity of the patient population, in terms of the microscopic diagnosis of the tumor and its grade, size, and the ability of the patients to carry out normal daily activities (Karnofsky performance status), it was not possible to come up with definitive conclusions about therapeutic efficacy. However, the survival data were no worse than those obtained by standard therapy at the time, and there were several patients who were long-term survivors, and most probably they were cured of their brain tumors.[8]

More recent clinical studies in the US and Japan

BNCT of patients with brain tumors and a few with cutaneous melanoma was resumed in the United States in the mid-1990s at the Brookhaven National Laboratory Medical Research Reactor (BMRR) and at Harvard/Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) using the MIT Research Reactor (MITR). For the first time, BPA was used as the boron delivery agent, and patients were irradiated with a collimated beam of higher energy epithermal neutrons, which had greater tissue-penetrating properties than thermal neutrons. This was well tolerated, but there were no significant differences in the MSTs compared to patients that had received conventional therapy.[9][10]

In Japan, Miyatake and Kawabata[13][14] have initiated several protocols employing the combination of BPA (500 mg/kg) and BSH (100 mg/kg), infused i.v. over 2 hrs, followed by neutron irradiation at Kyoto University Research Reactor Institute(KURRI). The MST of 10 patients was 15.6 months, with one long-term survivor (>5 years).[14] Based on experimental animal data,[32] which showed that BNCT in combination with X-irradiation produced enhanced survival compared to BNCT alone, Miyatake and Kawabata combined BNCT, as described above, with an X-ray boost.[13] A total dose of 20 to 30 Gy was administered, divided into 2 Gy daily fractions. The MST of this group of patients was 23.5 months and no significant toxicity was observed, other than hair loss (alopecia). These results suggest that the combination of BNCT with X-irradiation deserves further evaluation in a larger group of patients. In another Japanese trial, carried out by Yamamoto et al., BPA and BSH were infused over 1 hr, followed by BNCT at the Japan Research Reactor (JRR)-4 reactor.[33] Patients subsequently received an X-ray boost after completion of BNCT. The overall median survival time (MeST) was 27.1 months, and the 1 year and 2-year survival rates were 87.5 and 62.5%, respectively. Based on the reports of Miyatake, Kawabata, and Yamamoto, it appears that combining BNCT with an X-ray boost can produce a significant therapeutic gain. Further studies are needed to optimize this combined therapy and to evaluate it using a larger patient population.

Clinical studies in Finland

A team of clinicians and nuclear engineers at the Helsinki University Central Hospital and VTT Technical Research Center of Finland have treated approximately 200+ patients with recurrent malignant gliomas (glioblastomas) and head and neck cancer who had undergone standard therapy, recurred, and subsequently received BNCT at the time of their recurrence using BPA as the boron delivery agent.[11][12] The median time to progression in patients with gliomas was 3 months, and the overall MeST was 7 months. It is difficult to compare these results with other reported results in patients with recurrent malignant gliomas, but they are a starting point for future studies using BNCT as salvage therapy in patients with recurrent tumors. Even though it may be economically feasible,[34] no further studies are planned at this facility.

| Reactor Facility* | No. of patients & duration of trial | Delivery agent | Median survival time (months) | Reference no. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMRR, U.S.A | 53 (1994–1999) | BPA 250–330 mg/kg | 12.8 | [9] |

| MITR, MIT, U.S.A. | 20 (1996–1999) | BPA 250 or 350 mg/kg | 11.1 | [10] |

| KURRI, Japan | 40 (1998–2008) | BPA 500 mg/kg | 23.5 (primary + X-ray) | [13][14] |

| JRR4, Japan | 15 (1998–2007) | BPA 250 mg/kg + BSH 5 g | 10.8 (recurrent), 27.1 (+ X-ray) | [33] |

| R2-0, Studsvik Medical AB, Sweden | 30 (2001–2007) | BPA 900 mg/kg | 17.7 (primary) | [35][36] |

| FiR1, Finland | 50 (1999–2012) | BPA 290–400 mg/kg | 11.0 – 21.9 (primary), 7.0 (recurrent) | [11] |

| HFR, Netherlands | 26 (1997–2002) | BSH 100 mg/kg | 10.4 – 13.2 | [37] |

| * A more comprehensive compilation of data relating to BNCT clinical trials can be found in Radiation Oncology 7:146–167, 2012[2] | ||||

Clinical studies in Sweden

Finally, to conclude this section, the following is a brief summary of a clinical trial that was carried out in Sweden using BPA and an epithermal neutron beam, which had greater tissue penetration properties than the thermal beams originally used in Japan. This study differed significantly from all previous clinical trials in that the total amount of BPA administered was increased (900 mg/kg), and based on animal studies demonstrating enhanced uptake of BPA infiltrating tumor cells following a 6-hour infusion,[30] it was infused i.v. over 6 hours.[35][36][38] The longer infusion time of the drug was well tolerated by the 30 patients who were enrolled in this study. All were treated with 2 fields, and the average whole brain dose was 3.2–6.1 Gy (weighted), and the minimum dose to the tumor ranged from 15.4 to 54.3 Gy (w). There has been some disagreement among the Swedish investigators who carried out this study in terms of evaluation of the results. Based on incomplete survival data, the MeST was reported as 14.2 months and the time to tumor progression was 5.8 months.[35] More careful examination [36] of the complete survival data revealed that the MeST was 17.7 months compared to 15.5 months that has been reported for patients who received standard therapy of surgery, followed by radiotherapy (RT) and the drug temozolomide (TMZ).[39] Furthermore, the frequency of adverse events was lower after BNCT (14%) than after radiation therapy (RT) alone (21%) and both of these were lower than those seen following RT in combination with TMZ. If this improved survival data, obtained using the higher dose of BPA and a 6-hour infusion time, can be confirmed by others, preferably in a randomized clinical trial, it could represent a significant step forward in BNCT of brain tumors, especially if combined with a photon boost.

Clinical Studies of BNCT for extracranial tumors

Head and neck cancers

The single most important clinical advance over the past 10 years [40] has been the application of BNCT to treat patients with recurrent tumors of the head and neck region who had failed all other therapy. These studies were first initiated by Kato et al.[40] and subsequently followed by several other groups in Japan and by Kankaanranta and her co-workers in Finland.[12] All of these studies employed BPA as the boron delivery agent, either alone or in combination with BSH. A very heterogeneous group of patients with a variety of histopathologic types of tumors have been treated, the largest number of which had recurrent squamous cell carcinomas. Kato et al. have reported on a series of 26 patients with far-advanced cancer for whom there were no further treatment options.[40] Either BPA + BSH or BPA alone were administered by a 1 or 2 hr intravenous (i.v.) infusion, and this was followed by BNCT using an epithermal beam. In this series, there were complete regressions in 12 cases, 10 partial regressions, and progression in 3 cases. The MST was 13.6 months, and the 6-year survival was 24%. Significant treatment related complications ("adverse" events) included brain necrosis, osteomyelitis, transient mucositis, and alopecia.

Kankaanranta et al. have reported their results in a prospective Phase I/II study of 30 patients with inoperable, locally recurrent squamous cell carcinomas of the head and neck region.[12] Patients received either two or, in a few cases, one BNCT treatment using BPA (400 mg/kg), administered i.v. over 2 hours, followed by neutron irradiation. Of 29 evaluated patients, there were 13 complete and 9 partial remissions, with an overall response rate of 76%. The most common adverse event was oral mucositis, oral pain, and fatigue. Based on the clinical results, it was concluded that BNCT was effective for the treatment of inoperable, previously irradiated patients with head and neck cancer. Some responses were durable but progression was common, usually at the site of the previously recurrent tumor. As previously indicated in the section on neutron sources, all clinical studies have ended in Finland, based on economic difficulties of the two companies directly involved, VTT and Boneca. However, there is a possibility that clinical studies will be restarted in the future using an accelerator neutron source. Finally, a group in Taiwan has treated 12 patients with locally recurrent head and neck cancers at the Tsing Hua Open-pool Reactor (THOR) of the National Tsing Hua University.[41] Eleven of these patients received two fractions at 30-day intervals as part of a Phase I/II clinical trial with a total response rate of 58% with acceptable toxicity.

Other types of tumors

Melanoma

Other extracranial tumors that have been treated include malignant melanomas, which originally was carried out in Japan by Yutaka Mishima and his clinical team at Kobe University[42] using BPA and a thermal neutron beam. Local control was achieved in almost all patients, and some were cured of their disease. More recently, Junichi Hiratsuka and his colleagues at Kawasaki Medical School Hospital have treated patients with melanoma of the head and neck region, vulva and vagina with impressive clinical results.[43] Finally, the first clinical trial of BNCT in Argentina was performed in October 2003[44] and several patients with cutaneous melanomas also have been treated.[44]

Colorectal cancer

Two patients with colon cancer, which had spread to the liver, have been treated by Zonta et al. in Italy.[45] The first was treated in 2001 and the second in mid-2003. The patients received an i.v. infusion of BPA, followed by removal of the liver (hepatectomy). This was treated out side of the body (extracorporeal) by BNCT and then re-transplanted into the patient. The first patient did remarkably well and survived for over 4 years after treatment, but the other died within a month of cardiac complications.[46] Clearly, this is a very challenging approach for the treatment of hepatic metastases, and it is unlikely that it will ever be widely used. Nevertheless, the good clinical results in the first patient established proof of principle. Finally Yanagie and his colleagues in Japan have treated several patients with recurrent rectal cancer using BNCT. Although no long-term results have been reported, there was evidence of short-term clinical responses.[47]

Conclusions

BNCT represents a joining together of nuclear technology, chemistry, biology, and medicine to treat malignant gliomas and recurrent head and neck cancers. Sadly, the lack of progress in developing more effective treatments for these tumors has been part of the driving force that continues to propel research in this field. BNCT may be best suited as an adjunctive treatment, used in combination with other modalities, including surgery, chemotherapy and external beam radiation therapy for those malignancies, whether primary or recurrent, for which there are no effective therapies. Clinical studies have demonstrated the safety of BNCT. The challenge facing clinicians and researchers is how to move forward. Advantages of BNCT include the potential ability to selectively deliver a radiation dose to the tumor with a much lower dose to surrounding normal tissues. This is an important feature that makes BNCT particularly attractive for salvage therapy of patients with a variety of malignancies who already have been heavily irradiated. Second, although it may be only palliative, it can produce striking clinical responses, as evidenced by the experiences of several groups treating patients with recurrent, therapeutically refractory head and neck cancers.

Problems with NCT and BNCT that need to be solved include:

- The development of more tumor-selective boron delivery agents for BNCT. Similar problems are seen with Gd-NCT.

- Accurate, real time dosimetry to better estimate the radiation doses delivered to the tumor and normal tissues.

- Evaluation of recently constructed accelerator-based neutron sources as an alternative to nuclear reactors.

For a more detailed discussion of these problems and their solutions in BNCT, readers are referred to the published proceedings of the 14th, 15th, and 16th International Congresses on Neutron Capture Therapy (2011, 2014, and 2015)[14][48][49] and a recently published review on the current status of BNCT of high grade gliomas and recurrent cancers of the head and neck region.[3] If the problems enumerated above can be solved BNCT could have an important role in twenty-first century cancer treatment of those malignancies that are loco-regional and that are presently incurable by other therapeutic modalities.[50]

See also

- Particle therapy, Neutron, proton or heavy ions (e.g. carbon)

References

- ↑ Barth, R.F.; Soloway, A.H.; Fairchild, R.G. (1990). "Boron neutron capture therapy for cancer". Scientific American. 263 (4): 100–3, 106–7. Bibcode:1990SciAm.263d.100B. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican1090-100. PMID 2173134.

- 1 2 Barth, R.F.; Vicente, M.G.H.; Harling, O.K.; Kiger, W.S.; Riley, K.J.; Binns, P.J.; Wagner, F.M.; Suzuki, M.; Aihara, T.; Kato, I.; Kawabata, S. (2012). "Current status of boron neutron capture therapy of high grade gliomas and recurrent head and neck cancer". Radiation Oncology. 7: 146. doi:10.1186/1748-717X-7-146. PMC 3583064

. PMID 22929110.

. PMID 22929110. - 1 2 Moss, R.L. (2014). "Critical review with an optimistic outlook on boron neutron capture therapy (BNCT)". Applied Radiation and Isotopes. 88: 2–11. doi:10.1016/j.apradiso.2013.11.109.

- ↑ Sweet, W.H. (1951). "The uses of nuclear disintegration in the diagnosis and treatment of brain tumor". New England Journal of Medicine. 245 (23): 875–8. doi:10.1056/NEJM195112062452301. PMID 14882442.

- 1 2 Farr, L.E.; Sweet, W.H.; Robertson, J.S.; Foster, C.G.; Locksley, H.B.; Sutherland, D.L.; Mendelsohn, M.L.; Stickley, E.E. (1954). "Neutron capture therapy with boron in the treatment of glioblastoma multiforme". The American journal of roentgenology, radium therapy, and nuclear medicine. 71 (2): 279–93. PMID 13124616.

- ↑ Barth, R.F.; Coderre, J.A.; Vicente, M.G.H.; Blue, T.E. (2005). "Boron neutron capture therapy of cancer: Current status and future prospects". Clinical Cancer Research. 11 (11): 3987–4002. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-0035. PMID 15930333.

- 1 2 Vicente, M.G.H. (2006). "Boron in medicinal chemistry". Anti-Cancer Agents in Medicinal Chemistry. 6 (2): 73. doi:10.2174/187152006776119162.

- 1 2 3 Nakagawa, Y.; Pooh, K.; Kobayashi, T.; Kageji, T.; Uyama, S.; Matsumura, A.; Kumada, H. (2003). "Clinical review of the Japanese experience with boron neutron capture therapy and a proposed strategy using epithermal neutron beams". Journal of Neuro-Oncology. 62 (1–2): 87–99. doi:10.1023/A:1023234902479. PMID 12749705.

- 1 2 3 Diaz, A.Z. (2003). "Assessment of the results from the phase I/II boron neutron capture therapy trials at the Brookhaven National Laboratory from a clinician's point of view". Journal of Neuro-Oncology. 62 (1–2): 101–9. doi:10.1023/A:1023245123455. PMID 12749706.

- 1 2 3 Busse, P.M.; Harling, O.K.; Palmer, M.R.; Kiger, W.S.; Kaplan, J.; Kaplan, I.; Chuang, C.F.; Goorley, J.T.; et al. (2003). "A critical examination of the results from the Harvard-MIT NCT program phase I clinical trial of neutron capture therapy for intracranial disease". Journal of Neuro-Oncology. 62 (1–2): 111–21. doi:10.1007/BF02699938. PMID 12749707.

- 1 2 3 Kankaanranta, L.; Seppälä, T.; Koivunoro, H.; Välimäki, P.; Beule, A.; Collan, J.; Kortesniemi, M.; Uusi-Simola, J.; et al. (2011). "L-Boronophenylalanine-mediated boron neutron capture therapy for malignant glioma progressing after external beam radiation therapy: A Phase I study". International Journal of Radiation Oncology • Biology • Physics. 80 (2): 369–76. doi:10.1016/j.ijrobp.2010.02.031. PMID 21236605.

- 1 2 3 4 Kankaanranta, L.; Seppälä, T.; Koivunoro, H.; Saarilahti, K.; Atula, T.; Collan, J.; Salli, E.; Kortesniemi, M.; et al. (2012). "Boron neutron capture therapy in the treatment of locally recurred head-and-neck cancer: Final analysis of a Phase I/II trial". International Journal of Radiation Oncology • Biology • Physics. 82 (1): e67–75. doi:10.1016/j.ijrobp.2010.09.057. PMID 21300462.

- 1 2 3 4 Kawabata, S.; Miyatake, S.-I.; Kuroiwa, T.; Yokoyama, K.; Doi, A.; Iida, K.; Miyata, S.; Nonoguchi, N.; et al. (2009). "Boron neutron capture therapy for newly diagnosed glioblastoma". Journal of Radiation Research. 50 (1): 51–60. doi:10.1269/jrr.08043. PMID 18957828.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Miyatake, S.-I.; Kawabata, S.; Yokoyama, K.; Kuroiwa, T.; Michiue, H.; Sakurai, Y.; Kumada, H.; Suzuki, M.; et al. (2008). "Survival benefit of boron neutron capture therapy for recurrent malignant gliomas". Journal of Neuro-Oncology. 91 (2): 199–206. doi:10.1007/s11060-008-9699-x. PMID 18813875.

- 1 2 3 Coderre, J.A.; Morris, G.M. (1999). "The radiation biology of boron neutron capture therapy". Radiation research. 151 (1): 1–18. doi:10.2307/3579742. PMID 9973079.

- ↑ Nigg, D.W. (2003). "Computational dosimetry and treatment planning considerations for neutron capture therapy". Journal of Neuro-Oncology. 62 (1–2): 75–86. doi:10.1023/A:1023241022546. PMID 12749704.

- ↑ Soloway, A.H., Tjarks, W., Barnum, B.A., Rong, F-G., Barth, R.F., Codogni, I.M., and Wilson, J.G.: The chemistry of neutron capture therapy. Chemical Rev 98: 1515-1562, 1998.

- ↑ Cerullo, N.; Bufalino, D.; Daquino, G. (2009). "Progress in the use of gadolinium for NCT". Applied Radiation and Isotopes. 67 (7–8): S157–60. doi:10.1016/j.apradiso.2009.03.109. PMID 19410468.

- ↑ Yasui, L.S.; Andorf, C.; Schneider, L.; Kroc, T.; Lennox, A.; Saroja, K.R. (2008). "Gadolinium neutron capture in glioblastoma multiforme cells". International Journal of Radiation Biology. 84 (12): 1130–9. doi:10.1080/09553000802538092. PMID 19061138.

- ↑ Nemoto, H.; Cai, J.; Nakamura, H.; Fujiwara, M.; Yamamoto, Y. (1999). "The synthesis of a carborane gadolinium–DTPA complex for boron neutron capture therapy". Journal of Organometallic Chemistry. 581: 170–5. doi:10.1016/S0022-328X(99)00049-2.

- 1 2 Tokumitsu, H.; Hiratsuka, J.; Sakurai, Y.; Kobayashi, T.; Ichikawa, H.; Fukumori, Y. (2000). "Gadolinium neutron-capture therapy using novel gadopentetic acid–chitosan complex nanoparticles: In vivo growth suppression of experimental melanoma solid tumor". Cancer Letters. 150 (2): 177–82. doi:10.1016/S0304-3835(99)00388-2. PMID 10704740.

- ↑ De Stasio, G.; Rajesh, D.; Ford, J.M.; Daniels, M.J.; Erhardt, R.J.; Frazer, B.H.; Tyliszczak, T.; Gilles, M.K.; et al. (2006). "Motexafin-gadolinium taken up in vitro by at least 90% of glioblastoma cell nuclei". Clinical Cancer Research. 12 (1): 206–13. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-0743. PMID 16397044.

- ↑ Geninatti-Crich, S.; Alberti, D.; Szabo, I.; Deagostino, A.; Toppino, A.; Barge, A.; Ballarini, F.; Bortolussi, S.; et al. (2011). "MRI-guided neutron capture therapy by use of a dual gadolinium/boron agent targeted at tumour cells through upregulated low-density lipoprotein transporters". Chemistry. 17 (30): 8479–86. doi:10.1002/chem.201003741. PMID 21671294.

- ↑ Harling, O.K. (2009). "Fission reactor based epithermal neutron irradiation facilities for routine clinical application in BNCT—Hatanaka memorial lecture". Applied Radiation and Isotopes. 67 (7–8): S7–11. doi:10.1016/j.apradiso.2009.03.095. PMID 19428265.

- ↑ Yiguo, L, Pu X, Xiao, W; et al. Start-up of the first in-hospital neutron irradiator (IHNI-1) & Presentation of the BNCT development status in China (PDF). New Challenges in Neutron Capture Therapy 2010: Proceedings of the 14th International Congress on Neutron Capture Therapy. Buenos Aires. pp. 371–4. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 December 2013.

- ↑ Matsumura, A., Yamamoto, T., Nakai, K., and Kumada, H.: Proceedings of the 15th International Congress on Neutron Capture Therapy Impact of a new radiotherapy against cancer. Appl Radiat Isotopes 88: 1-246, 2014.

- ↑ Koivunoro, H., Green, S., Auterinen, I., and Kulvik, M.: The 16th International Congress on Neutron Capture Therapy (ICNCT-16). Appl Radiat Isotopes 106: 1-264, 2015.

- ↑ Mitsumoto,T, Yajima, S, Tsutsui, H; et al. Cyclotron-based neutron source for BNCT (PDF). New Challenges in Neutron Capture Therapy 2010: Proceedings of the 14th International Congress on Neutron Capture Therapy. Buenos Aires. pp. 519–22. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 October 2013.

- ↑ Sweet WH (1983). Practical problems in the past in the use of boron-slow neutron capture therapy in the treatment of glioblastoma multiforme. Proceedings of the First International Symposium on Neutron Capture Therapy. pp. 376–8.

- 1 2 Barth, R.F. (2015). "From the laboratory to the clinic: How translational studies in animals have lead [sic] to clinical advances in boron neutron capture therapy.". Appl Radiat Isotopes. 106: 22–28. doi:10.1016/j.apradiso.2015.06.016.

- ↑ Hatanaka, H.; Nakagawa, Y. (1994). "Clinical results of long-surviving brain tumor patients who underwent boron neutron capture therapy". International Journal of Radiation Oncology • Biology • Physics. 28 (5): 1061–6. doi:10.1016/0360-3016(94)90479-0. PMID 8175390.

- ↑ Barth, R.F.; Grecula, J.C.; Yang, W.; Rotaru, J.H.; Nawrocky, M.; Gupta, N.; Albertson, B.J.; Ferketich, A.K.; et al. (2004). "Combination of boron neutron capture therapy and external beam radiotherapy for brain tumors". International Journal of Radiation Oncology • Biology • Physics. 58 (1): 267–77. doi:10.1016/S0360-3016(03)01613-4. PMID 14697448.

- 1 2 Yamamoto, T.; Nakai, K.; Nariai, T.; Kumada, H.; Okumura, T.; Mizumoto, M.; Tsuboi, K.; Zaboronok, A.; et al. (2011). "The status of Tsukuba BNCT trial: BPA-based boron neutron capture therapy combined with X-ray irradiation". Applied Radiation and Isotopes. 69 (12): 1817–8. doi:10.1016/j.apradiso.2011.02.013. PMID 21393005.

- ↑ Kulvik, M.; Hermans, R.; Linnosmaa, I.; Shalowitz, J. (2015). "An economic model to assess the cost-benefit of BNCT". Appl Radiat Isotopes. 106: 3–9. doi:10.1016/j.apradiso.2015.08.021.

- 1 2 3 Henriksson, R.; Capala, J.; Michanek, A.; Lindahl, S.-Å.; Salford, L.G.; Franzén, L.; Blomquist, E.; Westlin, J.-E.; et al. (2008). "Boron neutron capture therapy (BNCT) for glioblastoma multiforme: A phase II study evaluating a prolonged high-dose of boronophenylalanine (BPA)". Radiotherapy and Oncology. 88 (2): 183–91. doi:10.1016/j.radonc.2006.04.015. PMID 18336940.

- 1 2 3 Sköld, K.; Gorlia, T.; Pellettieri, L.; Giusti, V.; H-Stenstam, B.; Hopewell, J.W. (2010). "Boron neutron capture therapy for newly diagnosed glioblastoma multiforme: An assessment of clinical potential". British Journal of Radiology. 83 (991): 596–603. doi:10.1259/bjr/56953620. PMC 3473677

. PMID 20603410.

. PMID 20603410. - ↑ Wittig, A., Hideghety, K., Paquis, P.; et al. (2002). Sauerwein, W.; Mass, R.; Wittig, A., eds. Current clinical results of the EORTC – study 11961. Research and Development in Neutron Capture Therapy Proc. 10th Intl. Congress on Neutron Capture Therapy. pp. 1117–22.

- ↑ Smith, D.R.; Chandra, S.; Barth, R.F.; Yang, W.; Joel, D.D.; Coderre, J. (15 November 2001). "Quantitative imaging and microlocalization of boron-10 in brain tumors and infiltrating tumor cells by SIMS ion microscopy: Relevance to neutron capture therapy" (PDF). Cancer Research. 61: 8179–8187.

- ↑ Stupp, R.; Hegi, M.E.; Mason, W.P.; Van Den Bent, M.J.; Taphoorn, M.J.B.; Janzer, R.C.; Ludwin, S.K.; Allgeier, A.; et al. (2009). "Effects of radiotherapy with concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide versus radiotherapy alone on survival in glioblastoma in a randomised phase III study: 5-year analysis of the EORTC-NCIC trial". The Lancet Oncology. 10 (5): 459–66. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70025-7. PMID 19269895.

- 1 2 3 Kato, I.; Fujita, Y.; Maruhashi, A.; Kumada, H.; Ohmae, M.; Kirihata, M.; Imahori, Y.; Suzuki, M.; et al. (2009). "Effectiveness of boron neutron capture therapy for recurrent head and neck malignancies". Applied Radiation and Isotopes. 67 (7–8): S37–42. doi:10.1016/j.apradiso.2009.03.103. PMID 19409799.

- ↑ Wang, L.W.; Wang, S.J.; Chu, P.Y.; Ho, C.Y.; Jiang, S.H.; Liu, Y.W.H.; Liu, Y.H.; Liu, H.M.; et al. (2011). "BNCT for locally recurrent head and neck cancer: Preliminary clinical experience from a phase I/II trial at Tsing Hua Open-Pool Reactor". Applied Radiation and Isotopes. 69 (12): 1803–6. doi:10.1016/j.apradiso.2011.03.008. PMID 21478023.

- ↑ Mishima, Y. (1996). "Selective thermal neutron capture therapy of cancer cells using their specific metabolic activities—melanoma as prototype". In Mishima, Y. Cancer neutron capture therapy. pp. 1–26. doi:10.1007/978-1-4757-9567-7_1. ISBN 978-1-4757-9569-1.

- ↑ Hiratsuka, J. Clinical results of BNCT for head and neck melanoma. 16th Intl' Congress on Neutron Capture Therapy, Helsinki, Finland, June 14–19, 2014

- 1 2 "The BNCT Project at the National Atomic Energy Commission (CNEA)". Comision Nacional de Energia Atomica. Archived from the original on 23 March 2012.

- ↑ Zonta, A.; Pinelli, T.; Prati, U.; Roveda, L.; Ferrari, C.; Clerici, A.M.; Zonta, C.; Mazzini, G.; et al. (2009). "Extra-corporeal liver BNCT for the treatment of diffuse metastases: What was learned and what is still to be learned". Applied Radiation and Isotopes. 67 (7–8): S67–75. doi:10.1016/j.apradiso.2009.03.087. PMID 19394837.

- ↑ Zonta, A.; Prati, U.; Roveda, L.; Ferrari, C.; Zonta, S.; Clerici, A.M.; Zonta, C.; Pinelli, T.; et al. (2006). "Clinical lessons from the first applications of BNCT on unresectable liver metastases". Journal of Physics: Conference Series. 41 (1): 484–95. Bibcode:2006JPhCS..41..484Z. doi:10.1088/1742-6596/41/1/054.

- ↑ Yanagie, H., Oyama, K., Hatae, R. et al. Clinical experiences of boron neutron capture therapy to recurrenced rectal cancers. Abstracts 16th Intl' Congress on Neutron Capture Therapy. Helsinki, Finland, June 14–19, 2014

- ↑ Altieri, S.; Bortolussi, S.; Barth, R.F.; Roveda, L.; Zonta, A. (2009). "Thirteenth International Congress on Neutron Capture Therapy". Applied Radiation and Isotopes. 67 (7–8): S1–2. doi:10.1016/j.apradiso.2009.03.009. PMID 19395267.

- ↑ Yamamoto, T.; Nakai, K.; Matsumura, A. (2011). "15th International Congress on Neutron Capture Therapy: Impact of a new radiotherapy against cancer". Applied Radiation and Isotopes. 88: 1–246.

- ↑ Barth, R.F. (2009). "Boron neutron capture therapy at the crossroads: Challenges and opportunities". Applied Radiation and Isotopes. 67 (7–8): S3–6. doi:10.1016/j.apradiso.2009.03.102. PMID 19467879.

External links

- Helsinki University Central Hospital and Technical Research Centre of Finland BNCT Project

- Boron and Gadolinium Neutron Capture Therapy for Cancer Treatment

- MIT Nuclear Reactor Lab overview of BNCT

- Washington State University Nuclear Radiation Center BNCT Overview