Body language

Body language is a language in which physical behavior, as opposed to words, is used to express feelings. Such behavior includes facial expressions, body posture, gestures, eye movement, touch and the use of space. Body language exists in both animals and humans, but this article focuses on interpretations of human body language. It is also known as kinesics.

Body language must not be confused with sign language, as sign languages are full languages like spoken languages and have their own complex grammar systems, as well as being able to exhibit the fundamental properties that exist in all languages.[1][2] Body language, on the other hand, does not have a grammar and must be interpreted broadly, instead of having an absolute meaning corresponding with a certain movement, so it is not a language like sign language,[3] and is simply termed as a "language" due to popular culture.

In a community, there are agreed-upon interpretations of particular behavior. Interpretations may vary from country to country, or culture to culture. On this note, there is controversy on whether body language is universal. Body language, a subset of nonverbal communication, complements verbal communication in social interaction. In fact some researchers conclude that nonverbal communication accounts for the majority of information transmitted during interpersonal interactions.[4] It helps to establish the relationship between two people and regulates interaction, but can be ambiguous. Hence, it is crucial to accurately read body language to avoid misunderstanding in social interactions.

Physical movement

Facial expression

Facial expression is integral when expressing emotions through the body. Combinations of eyes, eyebrow, lips, nose, and cheek movements help form different moods of an individual (e.g. happy, sad, depressed, angry, etc.).[5]

A few studies show that facial expression and bodily expression (i.e. body language) are congruent when interpreting emotions.[6][7] Behavioural experiments have also shown that recognition of facial expression is influenced by perceived bodily expression. This means that the brain processes the other's facial and bodily expressions simultaneously.[6] Subjects in these studies showed accuracy in judging emotions based on facial expression. This is because the face and the body are normally seen together in their natural proportions and the emotional signals from the face and body are well integrated.

Body postures

Emotions can also be detected through body postures. Research has shown that body postures are more accurately recognised when an emotion is compared with a different or neutral emotion.[8] For example, a person feeling angry would portray dominance over the other, and their posture would display approach tendencies. Comparing this to a person feeling fearful: they would feel weak, submissive and their posture would display avoidance tendencies,[8] the opposite of an angry person.

Sitting or standing postures also indicate one’s emotions. A person sitting till the back of their chair, leans forward with their head nodding along with the discussion implies that they are open, relaxed and generally ready to listen. On the other hand, a person who has their legs and arms crossed with the foot kicking slightly implies that they are feeling impatient and emotionally detached from the discussion.[5]

In a standing discussion, a person stands with arms akimbo with feet pointed towards the speaker could suggest that they are attentive and is interested in the conversation. However, a small difference in this posture could mean a lot.[5] Standing with arms akimbo is considered rude in Bali.

Open and expansive nonverbal posturing can also have downstream effects on testosterone and cortisol levels, which have clear implications for the study of human behavior [9]

Gestures

Gestures are movements made with body parts (e.g. hands, arms, fingers, head, legs) and they may be voluntary or involuntary.[5] Arm gestures can be interpreted in several ways. In a discussion, when one stands, sits or even walks with folded arms, this is normally not a welcoming gesture. It could mean that they have a closed mind and are most likely unwilling to listen to the speaker’s viewpoint. Another type of arm gesture also includes an arm crossed over the other, demonstrating insecurity and a lack of confidence.[5]

Hand gestures often signify the state of well-being of the person making them. Relaxed hands indicate confidence and self-assurance, while clenched hands may be interpreted as signs of stress or anger. If a person is wringing their hands, this demonstrates nervousness and anxiety.[5]

Finger gestures are also commonly used to exemplify one's speech as well as denote the state of well-being of the person making them. In certain cultures, pointing using one's index finger is deemed acceptable. However, pointing at a person may be viewed as aggressive in other cultures—for example, people who share Hindu beliefs consider finger pointing offensive. Instead, they point with their thumbs.[10] Likewise, the thumbs up gesture could show "OK" or "good" in countries like the US, France and Germany. But this same gesture is insulting in other countries like Iran, Bangladesh and Thailand, where it is the equivalent of showing the middle finger in the US.[10]

In most cultures the Head Nod is used to signify 'Yes' or agreement. It's a stunted form of bowing - the person symbolically goes to bow but stops short, resulting in a nod. Bowing is a submissive gesture so the Head Nod shows we are going along with the other person's point of view. Research conducted with people who were born deaf, dumb and blind shows that they also use this gesture to signify 'Yes', so it appears to be an inborn gesture of submission.[11]

Handshakes

Handshakes are regular greeting rituals and are commonly done on meeting, greeting, offering congratulations or after the completion of an agreement. They usually indicate the level of confidence and emotion level in people.[5] Studies have also categorised several handshake styles,[10] e.g. the finger squeeze, the bone crusher (shaking hands too strongly), the limp fish (shaking hands too weakly), etc. Handshakes are popular in the US and are appropriate for use between men and women. However, in Muslim cultures, men may not shake hands or touch women in any way and vice versa. Likewise, in Hindu cultures, Hindu men may never shake hands with women. Instead, they greet women by placing their hands as if praying.

A firm, friendly handshake has long been recommended in the business world as a way to make a good first impression, and the greeting is thought to date to ancient times as a way of showing a stranger you had no weapons. [12]

Other types of physical movements

Covering one’s mouth suggests suppression of feeling and perhaps uncertainty. This could also mean that they are thinking hard and may be unsure of what to say next.[5] What you communicate through your body language and nonverbal signals affects how others see you, how well they like and respect you, and whether or not they trust you.

Unfortunately, many people send confusing or negative nonverbal signals without even knowing it. When this happens, both connection and trust are damaged.

Other subcategories

Oculesics

Oculesics, a subcategory of body language, is the study of eye movement, eye behavior, gaze, and eye-related nonverbal communication. As a social or behavioral science, oculesics is a form of nonverbal communication focusing on deriving meaning from eye behavior.[13] It is also crucial to note that Oculesics is culturally dependent. For example, in traditional Anglo-Saxon culture, avoiding eye contact usually portrays a lack of confidence, certainty, or truthfulness.[14] However, in the Latino culture, direct or prolonged eye contact means that you are challenging the individual with whom you are speaking or that you have a romantic interest in the person.[14] Also, in many Asian cultures, prolonged eye contact may be a sign of anger or aggression.

Haptics

Haptics, a subcategory of Body Language, is the study of touching and how it is used in communication.[15] As such, handshakes, holding hands, back slapping, high fives, brushing up against someone or pats all have meaning.[15]

Based on the Body Language Project,[15] touching is the most developed sense at birth and formulates our initial views of the world. Touching can be used to sooth, for amusement during play, to flirt, to expressing power and maintaining bonds between people such as with baby and mother. Touching can carry distinct emotions and also show the intensity of those emotions. Touch absent of other cues can signal anger, fear, disgust, love, gratitude and sympathy depending on the length and type of touching that is performed. Many factors also contribute to the meaning of touching such as the length of the touch and location on the body in which the touching takes place.

Research has also shown that people can accurately decode distinct emotions by merely watching others communicate via touch.[16]

Heslin outlines five haptic categories:[17]

Functional/professional which expresses task-orientation

Donald Walton[18] stated in his book that touching is the ultimate expression of closeness or confidence between two people, but not seen often in business or formal relationships. Touching stresses how special the message is that is being sent by the initiator. "If a word of praise is accompanied by a touch on the shoulder, that’s the gold star on the ribbon," wrote Walton.[18]

Social/polite which expresses ritual interaction

A study by Jones and Yarbrough[19] regarded communication with touch as the most intimate and involving form which helps people to keep good relationships with others. For example, Jones and Yarbrough explained that strategic touching is a series of touching usually with an ulterior or hidden motive thus making them seem to be using touch as a game to get someone to do something for them.[19]

Friendship/warmth which expresses idiosyncratic relationship

Love/intimacy which expresses emotional attachment

Public touch can serve as a ‘tie sign’ that shows others that your partner is “taken”.[20] When a couple is holding hands, putting their arms around each other, this is a ‘tie sign’ showing others that they are together. The use of ‘tie signs’ are used more often by couples in the dating and courtship stages than between their married counterparts according to Burgoon, Buller, and Woodall.[21]

Sexual/arousal which expresses sexual intent.

The amount of touching that occurs within a culture is also culturally dependent.

Proxemics

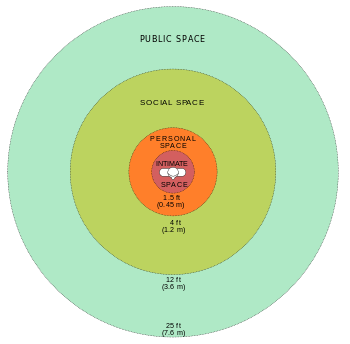

Another notable area in the nonverbal world of body language is that of spatial relationships, which is also known as Proxemics. Introduced by Edward T. Hall in 1966, proxemics is the study of measurable distances between people as they interact with one another.[22] In the book, Body Language,[23] Julius Fast mentioned that the signals that we send or receive to others through body language are reactions to others’ invasions of our personal territories, which links Proxemics an important part of Body Language.

Hall also came up with four distinct zones in which most men operate:[22]

Intimate distance for embracing, touching or whispering

- Close phase – less than 6 inches (15 cm)

- Far phase – 6 to 18 inches (15 to 46 cm)

Personal distance for interactions among good friends or family members

- Close phase – 1.5 to 2.5 feet (46 to 76 cm)

- Far phase – 2.5 to 4 feet (76 to 122 cm)

Social distance for interactions among acquaintances

- Close phase – 4 to 7 feet (1.2 to 2.1 m)

- Far phase – 7 to 12 feet (2.1 to 3.7 m)

Public Distance used for public speaking

- Close phase – 12 to 25 feet (3.7 to 7.6 m)

- Far phase – 25 feet (7.6 m) or more.

In addition to physical distance, the level of intimacy between conversants can be determined by "socio-petal socio-fugal axis", or the "angle formed by the axis of the conversants' shoulders".[24]

Changing the distance between two people can convey a desire for intimacy, declare a lack of interest, or increase/decrease domination.[25] It can also influence the body language that is used. For example, when people talk they like to face each other. If forced to sit side by side, their body language will try to compensate for this lack of eye-to-eye contact by leaning in shoulder-to-shoulder.[25]

It is important to note that as with other types of Body Language, proximity range varies with culture. Hall suggested that "physical contact between two people ... can be perfectly correct in one culture, and absolutely taboo in another".[26] In Latin America, people who may be complete strangers may engage in very close contact. They often greet one another by kissing on the cheeks. North Americans, on the other hand, prefer to shake hands. While they have made some physical contact with the shaking of the hand, they still maintain a certain amount of physical space between the other person.[27]

Tone of voice

Tone of voice is a combination of spoken language and body language.

The manner in which something is said can affect how it should be interpreted. Shouting, smiling, irony and so on may add a layer of meaning which is neither pure body language nor speech.

Universal vs. culture-specific

Scholars have long debated on whether body language, particularly facial expressions, are universally understood. In Darwin’s (1872) evolutionary theory, he postulated that facial expressions of emotion are inherited.[28] On the other hand, scholars have questioned if culture influences one’s bodily expression of emotions. Broadly, the theories can be categorized into two models:

Cultural Equivalence Model

The Cultural Equivalence Model predicts that "individuals should be equally accurate in understanding the emotions of ingroup and outgroup members" (Soto & Levenson, 2009). This model is rooted in Darwin’s (1872) evolutionary theory, where he noted that both humans and animals share similar postural expressions of emotions such as anger/aggression, happiness, and fear.[29] These similarities support the evolution argument that social animals (including humans) have a natural ability to relay emotional signals with one another, a notion shared by several academics (Chevalier-Skolnikoff, 1974; Linnankoski, Laakso, Aulanko, & Leinonen, 1994). Where Darwin notes similarity in expression among animals and humans, the Cultural Equivalence Model notes similarity in expression across cultures in humans, even though they may be completely different.

One of the strongest pieces of evidence that supports this model was a study conducted by Ekman and Friesen (1971), where members of a preliterate tribe in Papua New Guinea reliably recognized the facial expressions of individuals from the United States. Culturally isolated and with no exposure to US media, there was no possibility of cross-cultural transmission to the Papuan tribesmen.[30]

Cultural Advantage Model

On the other hand, the Cultural Advantage Model predicts that individuals of the same race "process the visual characteristics more accurately and efficiently than other-race faces".[31] Other factors that increase accurate interpretation include familiarity with nonverbal accents.[32]

There are numerous studies that support both the Cultural Equivalence Model and the Cultural Advantage Model, but reviewing the literature indicates that there is a general consensus that seven emotions are universally recognized, regardless of cultural background: happiness, surprise, fear, anger, contempt, disgust, and sadness.[33]

Recently, scholars have shown that the expressions of pride and shame are universal. Tracy and Robins (2008) concluded that the expression of pride includes an expanded posture of the body with the head tilted back, with a low-intensity face and a non-Duchenne smile (raising the corner of the mouth). The expression of shame includes the hiding of the face, either by turning it down or covering it with the hands.[30]

Applications

Fundamentally, body language is seemed as an involuntary and unconscious phenomena that adds to the process of communication. Despite that, there have been certain areas where the conscious harnessing of body language - both in action and comprehension - have been useful. The use of body language has also seen an increase in application and use commercially, with large volumes of books and guides published designed to teach people how to be conscious of body language, and how to use it to benefit them in certain scenarios.[23]

The use of body language can be seen in a wide variety of fields. Body language has seen application in instructional teaching in areas such as second-language acquisition[34] and also to enhance the teaching of subjects like mathematics. A related use of body language is as a substitution to verbal language to people who lack the ability to use that, be it because of deafness or aphasia. Body language has also been applied in the process of detecting deceit through micro-expressions, both in law enforcement and even in the world of poker.[35]

Instructional teaching

Second-language acquisition

The importance of body language in second-language acquisition was inspired by the fact that to successfully learn a language is to achieve discourse, strategic, and sociolinguistic competencies.[36] Sociolinguistic competence includes understanding the body language that aids the use of a particular language. This is usually also highly culturally influenced. As such, a conscious ability to recognize and even perform this sort of body language is necessary to achieve fluency in a language beyond the discourse level.

The importance of body language to verbal language use is the need to eliminate ambiguity and redundancy in comprehension.[36] Pennycook (1985) suggests to limit the use of non-visual materials to facilitate the teaching of a second language to improve this aspect of communication. He calls this being not just bilingual but also 'bi-kinesic'.[37]

Enhancing teaching

Body language can be a useful aid not only in teaching a second language, but also in other areas. The idea behind using it is as a nonlinguistic input.[38] It can be used to guide, hint, or urge a student towards the right answer. This is usually paired off with other verbal methods of guiding the student, be it through confirmation checks or modified language use. Tai[39] in his 2014 paper provides a list of three main characteristic of body language and how they influence teaching. The features are intuition, communication, and suggestion.

- The intuitive feature of body language used in teaching is the exemplification of the language, especially individual words, through the use of matching body language. For example, when teaching about the word "cry", teachers can imitate a crying person. This enables a deeper impression which is able to lead to greater understanding of the particular word.[39]

- The communicative feature is the ability of body language to create an environment and atmosphere that is able to facilitate effective learning. A holistic environment is more productive for learning and the acquisition for new knowledge.[39]

- The suggestive feature of body language uses body language as a tool to create opportunities for the students to gain additional information about a particular concept or word through pairing it with the body language itself.[39]

Detecting deceit

Law enforcement

Body language has seen use in the area of law enforcement. The relevance of body language in this area can be seen in the numerous Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) Law Enforcement Bulletins[40][41] that have included it in their articles. The application of body language in law enforcement goes both ways. Members of law enforcement can use body language to catch unspoken clues by suspects or even victims, this enables a more calculated and more comprehensive judgement of people. The other side of body language is that of the investigators' themselves. The body language of the members of law enforcement might influence the accuracy of eyewitness accounts.[42]

Poker

The game of poker involves not only an understanding of probability , but also the competence of reading and analyzing the body language of the opponents. A key component of poker is to be able to "cheat" the opponents. To spot these cheats, players must have the ability to spot the individual "ticks" of their opponents. Players also have to look out for signs that an opponent is doing well.

Kinesics

Kinesics is the study and interpretation of nonverbal communication related to the movement of any part of the body or the body as a whole;[43] in layman's terms, it is the study of body language. However, Ray Birdwhistell, who is considered the founder of this area of study, never used the term body language, and did not consider it appropriate. He argued that what can be conveyed with the body does not meet the linguist's definition of language.[3]

Birdwhistell pointed out that "human gestures differ from those of other animals in that they are polysemic, that they can be interpreted to have many different meanings depending on the communicative context in which they are produced". And, he "resisted the idea that 'body language' could be deciphered in some absolute fashion". He also indicated that "every body movement must be interpreted broadly and in conjunction with every other element in communication".[3]

Despite that, body language is still more widely used than kinesics.

See also

References

- ↑ Klima, Edward S.; & Bellugi, Ursula. (1979). The signs of language. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-80795-2.

- ↑ Sandler, Wendy; & Lillo-Martin, Diane. (2006). Sign Language and Linguistic Universals. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- 1 2 3 Barfield, T (1997). The dictionary of anthropology. Illinois: Blackwell Publishing.

- ↑ Onsager, Mark. "Understanding the Importance of Non-Verbal Communication"], Body Language Dictionary, New York, 19 May 2014. Retrieved on 26 October 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Kurien, Daisy N (March 1, 2010). "Body Language: Silent Communicator at the Workplace". IUP Journal of Soft Skills. 4 (1/2): 29–36.

- 1 2 Gu, Yuanyuan; Mai, Xiaoqin; Luo, Yue-jia; Di Russo, Francesco (23 July 2013). "Do Bodily Expressions Compete with Facial Expressions? Time Course of Integration of Emotional Signals from the Face and the Body". PLoS ONE. 8 (7): e66762. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0066762.

- ↑ Kret, ME; Pichon, S; Grezes, J; de Gelder, B (Jan 15, 2011). "Similarities and differences in perceiving threat from dynamic faces and bodies. An fMRI study". NEUROIMAGE. 54 (2): 1755–1762. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.08.012. PMID 20723605.

- 1 2 Mondloch, Catherine J.; Nelson, Nicole L.; Horner, Matthew; Pavlova, Marina (10 September 2013). "Asymmetries of Influence: Differential Effects of Body Postures on Perceptions of Emotional Facial Expressions". PLoS ONE. 8 (9): e73605. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0073605.

- ↑ Carney, Dana R.; Cuddy, Amy J.; Yap, Andy J. (8 April 2010). "Power Posing:Brief Nonverbal Displays Affect Neuroendocrine Levels and Risk Tolerance". Psychological Science. 21: 1363–8. doi:10.1177/0956797610383437. PMID 20855902.

- 1 2 3 Black, Roxie M. (2011). "Cultural Considerations of Hand Use". Journal of Hand Therapy. 24 (2): 104–111. doi:10.1016/j.jht.2010.09.067.

- ↑ Pease, Allan & Barbara (2004). The Definitive Book of Body Language. Orion House, 5 Upper St Martin's Lane, London WC2H 9EA: Orion Books Ltd. p. 230. ISBN 0-75286-118-2.

- ↑ Ramadas, Nidhin. "Handshake". Beckman Institute. Retrieved 13 September 2016.

- ↑ Sullivan, Larry E. (31 August 2009). The SAGE Glossary of the Social and Behavioral Sciences (illustrated ed.). SAGE Publications. p. 577. ISBN 1412951437.

- 1 2 Cruz, William. "Differences In Nonverbal Communication Styles between Cultures: The Latino-Anglo Perspective". Leadership and Management in Engineering. 1 (4): 51–53. doi:10.1061/(ASCE)1532-6748(2001)1:4(51). ISSN 1532-6748. Retrieved 14 October 2014.

- 1 2 3 "Haptics: The Use Of Touch In Communication". Body Language Project. Retrieved 14 October 2014.

- ↑ Hertenstein, Matthew J.; Keltner, Dacher; App, Betsy; Bulleit, Brittany A.; Jaskolka, Ariane R. (2006). "Touch Communicates Distinct Emotions" (PDF). Emotion. 6 (3): 528–533. doi:10.1037/1528-3542.6.3.528.

- ↑ Heslin, R. (1974, May) Steps toward a taxomony of touching. Paper presented to the annual meeting of the Midwestern Psychological Association, Chicago, IL.

- 1 2 Walton, Donald (May 1989). Are You Communicating?: You Can't Manage Without It (First ed.). McGraw-Hill Companies. p. 244. ISBN 0070680523.

- 1 2 Jones, Stanley E. & A. Elaine Yarbrough; Yarbrough, A. Elaine (1985). "A naturalistic study of the meanings of touch". Communication Monographs. 52 (1): 19–56. doi:10.1080/03637758509376094. Retrieved 14 October 2014.

- ↑ Morris, Desmond (1977). Manwatching: A Field Guide to Human Behavior (illustrated ed.). Abrams. p. 320. ISBN 0810913100.

- ↑ Burgoon, Judee K.; Buller, David B.; Woodall, William Gill (1996). Nonverbal Communication: The Unspoken Dialogue (2nd ed.). McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0070089957.

- 1 2 Hall, Edward T. (1966). The Hidden Dimension. Anchor Books. ISBN 0-385-08476-5

- 1 2 Fast, Julius (2014). Body Language. Open Road Media. ISBN 1497622689.

- ↑ Moore, Nina (2010). Nonverbal Communication:Studies and Applications. New York: Oxford University Press

- 1 2 "The significance of Body Language" (PDF). Retrieved 14 October 2014.

- ↑ Hall, Edward T. (1968). "Proxemics" (PDF). Current Anthropology. The University of Chicago Press. 9 (2/3): 88. doi:10.1086/200975. JSTOR http://www.jstor.org/stable/2740724. Retrieved 14 October 2014.

- ↑ "Proxemics and culture". Retrieved 14 October 2014.

- ↑ Ekman, Paul (1971). "Universals and cultural differences in facial expression of emotion" (PDF). Nebraska Symposium on Motivation. 19: 207–283.

- ↑ Soto, Jose Angel; Levenson, Robert W. (2009). "Emotion recognition across cultures: The influence of ethnicity on empathic accuracy and physiological linkage". Emotion. 9 (6): 874–884. doi:10.1037/a0017399.

- 1 2 Tracy, Jessica L.; Robins, Richard W. (2008). "The nonverbal expression of pride: Evidence for cross-cultural recognition" (PDF). Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 94 (3): 516–530. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.94.3.516.

- ↑ O'Toole, Alice J.; Peterson, Jennifer; Deffenbacher, Kenneth A. (1996). "An "other-race effect" for categorizing faces by sex". Perception. 25 (6): 669–676. doi:10.1068/p250669.

- ↑ Marsh, A.A.; Elfenbein, H.A.; Ambady, N. (2003). "Nonverbal "accents": Cultural differences in facial expressions of emotion". Psychological Science. 14 (4): 373–376. doi:10.1111/1467-9280.24461. PMID 12807413.

- ↑ Russell, James A. (1994). "Is There Universal Recognition of Emotion From Facial Expression? A Review of the Cross-Cultural Studies" (PDF). Psychological Bulletin. 115 (1): 102–141. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.115.1.102. PMID 8202574.

- ↑ Gregersen, Tammy S. (July 2007). "Language learning beyond words: Incorporating body language into classroom activities". Reflections on English Language Teaching. 6: 51–64.

- ↑ Caro, Mike (1994). The Body Language of Poker: Mike Caro's Book of Tells.

- 1 2 Kellerman, Susan (1992). "I see what you mean: The role of kinesic behaviour in listening and the implications for foreign and second language learning". Applied Linguistics. 13 (3): 239–258. doi:10.1093/applin/13.3.239.

- ↑ Pennycook, Alastair (1985). "Actions speak louder than words: Paralanguage, communication, and education". TESOL Quarterly. 19 (2): 259–282. doi:10.2307/3586829.

- ↑ Brandl, Klaus (2007). Communicative Language Teaching in Action: Putting Principles to Work.

- 1 2 3 4 Tai, Yuanyuan (2014). "The Application of Body Language in English Teaching". Journal of Language Teaching and Research. 5 (5): 1205–1209. doi:10.4304/jltr.5.5.1205-1209.

- ↑ Pinizzoto, Anthony J.; Davis, Edward F.; Miller III, Charles E. (March 2006). "Dead Right". FBI Law Enforcement Bulletin. 75 (3): 1–8.

- ↑ Matsumoto, David; Hyi Sung, Hwang; Skinner, Lisa; Frank, Mark (June 2011). "Evaluating Truthfulness and Detecting Deception". FBI Law Enforcement Bulletin. 80 (6): 1–8.

- ↑ Eyewitness Evidence: A Guide for Law Enforcement. October 1999.

- ↑ Danesi, M (2006). "Kinesics". Encyclopedia of language & linguistics.: 207–213.