Bloodstain pattern analysis

| Forensic science |

|---|

|

| Physiological sciences |

| Social sciences |

| Forensic criminalistics |

| Digital forensics |

| Related disciplines |

| Related articles |

Bloodstain pattern analysis (BPA), one of several specialties in the field of forensic science, involves the study and analysis of bloodstains at a known or suspected violent crime scene with the goal of helping investigators draw conclusions about the nature, timing and other details of the crime.

The use of bloodstains as evidence is not new; however, the application of modern science has brought it to a higher level since the 1970s and '80s. New technologies, especially advances in DNA analysis, are available for detectives and criminologists to use in solving crimes and apprehending offenders.

The science of bloodstain pattern analysis applies scientific knowledge from other fields to solve practical problems. Bloodstain pattern analysis draws on the scientific disciplines of biology, chemistry, mathematics and physics. If an analyst follows a scientific process, this applied science can produce strong, solid evidence, making it an effective tool for investigators, although care does need to be taken when relying on bloodstain pattern analysis in criminal cases. A report released by The National Academy of Sciences calls for more standardization within the field. The report highlights the ability of blood spatter analysts to overstate their qualifications and the reliability of their methods in the court room.[1]

History

Bloodstain pattern analysis has been used informally for centuries, but the first modern study of blood stains was in 1895. Dr. Eduard Piotrowski of the University of Kraków published a paper titled "On the formation, form, direction, and spreading of blood stains after blunt trauma to the head."[2][3] A number of publications describing various aspects of blood stains were published, but his publication did not lead to a systematic analysis. LeMoyne Snyder's widely used book Homicide Investigation (first published in 1941 and updated occasionally through at least the 1970s) also briefly mentioned details that later bloodstain experts would expand upon (e.g., that blood dries at a relatively predictable rate; that arterial blood is a brighter red color than other blood; that bloodstains tend to fall in certain patterns based on the motion of an attacker and victim).[4]

The second modern origin of the study of bloodstain pattern analysis is the Sam Sheppard case in 1954, when the wife of an osteopathic physician was beaten to death in her home. Further growth of interest and use of the significance of bloodstain evidence is a direct result of the scientific research and practical applications of bloodstain theory by Herbert Leon MacDonell of Corning, New York. His research resulted in his publication of the first modern treatise on bloodstain analysis, entitled "Flight Characteristics and Stain Patterns of Human Blood" (1971).

The first formal bloodstain training course was given by MacDonnel in 1973 in Jackson, Mississippi. In 1983, the International Association of Bloodstain Pattern Analysts was founded by a group of blood stain analysts to help develop the emerging field of bloodstain pattern analysis.[3]

Blood

Blood is a tissue that is circulated within the body to assist other parts of the body. This connective tissue has specialized cells that allow it to carry out its complex functions. For a healthy person, approximately 8% of their total weight is blood. For a 70 kg (154 lb.) individual, this equates to 5.6 L (12 US pints).

Biological considerations

Blood contains three components or blood cells that are suspended within plasma. The three components are erythrocytes, leukocytes, and trombocytes.

- Erythrocytes, also known as red blood cells, are transporters. The role of erythrocytes is to transport oxygen. To do this, they contain great quantities of hemoglobin, which carry oxygen molecules and give blood its distinct red colour. Blood that has passed through the heart and been oxygenated (oxygenated blood travels through the arteries) tends to have a brighter shade of red as opposed to blood that is returning to the heart (in the veins). There are about 30 trillion erythrocytes circulating in the human blood at any given time.

- Leukocytes, also known as white blood cells, are the body's defenders. The role of leukocytes is to defend against harmful bacteria, viruses and microorganisms. There are five different types of leukocytes. They all have different sizes, shapes, structures, and functions. Leukocytes fight infection and disease. There are about 430 billion leukocytes circulating in the human blood at any given time (~1 per 700 erythrocytes). Pus is made up of leukocytes left in an affected area during and after fighting harmful substances or organisms that infect the body.

- Platelets are formed in the bone marrow. These particular blood cells contain cytoplasm and are enclosed by a membrane, but do not have a nucleus. They play a major role in hemostasis (control of bleeding) by plugging up a breach in a vessel. They are important for forming blood clots. If a person has an abnormally low platelet count, a condition known as thrombocytopenia, blood clots more slowly.

Plasma is the yellowish fluid that carries the erythrocytes, leukocytes, and platelets. It is composed of water (92%), proteins (7%), and other materials such as salts, waste, and hormones, among others. Many of these proteins are clotting factors, which are important along with platelets for forming blood clots; clotting factor deficiencies can cause prolonged and excessive bleeding, a condition called hemophilia. Plasma makes up about 55% of blood. The remaining 45% is the blood cells. Because plasma is less dense than the blood cells, it can be easily separated. Plasma does not separate from blood cells whilst circulating in the bloodstream because it is in a constant state of agitation.

Chemical considerations

Upon exiting the body, bloodstains transit from bright red to dark brown, which is attributed to oxidation of oxy-hemoglobin (HbO2) to methemoglobin (met-Hb) and hemichrome (HC). The fractions of HbO2, met-Hb and HC in a bloodstain can be used for age determination of bloodstains and can be measured by Reflectance Spectroscopy 1.

- In vivo hemoglobin molecules are mainly present in two forms: one without oxygen, de-oxyhemoglobin (Hb) and one saturated with oxygen, oxy-hemoglobin (HbO2), both have iron in the Fe2+ state. HbO2 can auto-oxidize into met-Hb, which contains iron in the Fe3+ state. Met-Hb is incapable of binding oxygen. When met-Hb is formed in vivo it will be reduced back to Hb by reductase protein cytochrome b5, resulting in a small part (<1%) of met-Hb in a healthy in vivo situation.

- Outside the body hemoglobin saturates completely with oxygen in the ambient environment to HbO2. Due to a decreasing availability of cytochrome b5, necessary for reduction of met-Hb, the transition of HbO2 into met-Hb will, in contrast to inside the body, no longer be reversed. Once hemoglobin is autooxidized to met-Hb it will denature to hemichrome (HC), which is formed by an internal conformation change to the heme group.

Physical considerations

In physics there are two continuous physical states of matter, solid and fluid. Once blood has left the body it behaves as a fluid and all physical laws apply.

- Gravity acts on blood (without the body's influence) as soon as it exits the body. Given the right circumstances blood can act according to ballistic theory.

- Viscosity is the amount of internal friction in the fluid. It describes the resistance of a liquid to flow.

- Surface tension is the force that maintains the shape of a drop of liquid, such as blood. When two fluids are in contact with each other (blood and air) there are forces attracting all molecules to each other.

Blood spatter flight characteristics

Experiments with blood have shown that a drop of blood tends to form into a sphere in flight rather than the artistic teardrop shape. This is what one would expect of a fluid in freefall. The formation of the sphere is a result of surface tension that binds the molecules together.

This spherical shape of blood in flight is important for the calculation of the angle of impact (incidence) of blood spatter when it hits a surface. That angle will be used to determine the point from which the blood originated which is called the Point of Origin or more appropriately the Area of Origin.

A single spatter of blood is not enough to determine the Area of Origin at a crime scene. The determination of the angles of impact and placement of the Area of Origin should be based on the consideration of a number of stains and preferably stains from opposite sides of the pattern to create the means to triangulate.

Determining angles of impact

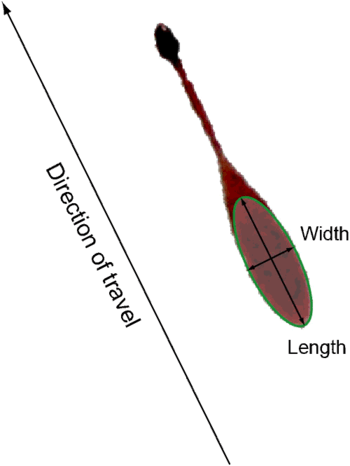

As mentioned earlier, a blood droplet in freefall has the shape of an oscillating sphere. Should the droplet strike a surface and a well-formed stain is produced, an analyst can determine the angle at which this droplet struck the surface. This is based on the relationship between the length of the major axis, minor axis, and the angle of impact.

A well-formed stain is in the shape of an ellipse (see figure 1). Dr. Victor Balthazard, and later Dr. Herbert Leon MacDonell, realized that the width-length ratio of the ellipse is the sine of the impact angle. Accurate measurement of the stain thus allows easy calculation of the impact angle.

Angles of impact

Because of the three-dimensional aspect of trajectories there are three angles of impact:

- alpha (α), the impact angle of the bloodstain path moving out from the surface (see figure 2 with alpha at the top by the stain).

- beta (β), the angle of the bloodstain path pivoting about the vertical (z) axis (see figure 2 with beta extended to the floor).

- gamma (γ), the angle of the bloodstain path measured from the true vertical (plumb) of the surface (see figure 2 showing plumb line and extended angle from stain).

All three angles are related through the following trigonometric equations:

where

- = length of ellipse (major axis)

- = width of ellipse (minor axis)

Accurately measuring the stain and calculating the angle of impact requires due diligence of the analyst. In the past analysts have used a variety of instruments. Methods currently used include:

- Viewing loupe with an embedded scale in 0.2 mm increments or better that is placed over the stain. The analyst then uses a scientific calculator or spreadsheet to complete the angle calculations.

- Bloodstain Pattern Analysis (BPA) software that superimposes an ellipse over a scaled close-up image of an individual bloodstain, then automatically calculates the angles of impact.

Using BPA software such as HemoSpat produces a very accurate result that is measurable and reproducible.

Point and area of convergence

To determine the point/area of convergence an analyst has to determine the path the blood droplets travelled. The tangential flight path of individual droplets can be determined by using the angle of impact and the offset angle of the resulting bloodstain. “Stringing” stains is a method of visualizing this. For the purpose of the point of convergence, only the top view of the flight paths is required. Note that this is a two-dimensional (2D) and not a three-dimensional (3D) intersection.

- The point of convergence is the intersection of two bloodstain paths, where the stains come from opposite sides of the impact pattern. (see figure 3)

- The area of convergence is the box formed by the intersection of several stains from opposite sides of the impact pattern. (see figure 4)

In the past, some analysts have drawn lines along the major axes of the stains and brought them to an area of convergence on the wall. Instead of using a top-down view, they used a front view. This provides a false point/area of convergence.

Area of origin

The area of origin is the area in three-dimensional space where the blood source was located at the time of the bloodletting incident. The area of origin includes the area of convergence with a third dimension in the z direction. Since the z-axis is perpendicular to the floor, the area of origin has three dimensions and is a volume.

The term point of origin has also been accepted to mean the same thing. However, it has been argued, there are problems associated to this term. First, a blood source is not a point source. To produce a point source the mechanism would have to be fixed in three-dimensional space and have an aperture where only a single blood droplet is released at a time, with enough energy to create a pattern. This does not seem likely. Second, bodies are dynamic. Aside from the victim physically moving, skin is elastic and bones break. Once a force is applied to the body there will be an equal and opposite reaction to the force applied by the aggressor (Newton's third law of motion). Part of the force will move the blood source, even a millimetre, and change the origin while it is still producing blood. So the source becomes contained in a three-dimensional volume, or region.

As with the area of convergence, the area of origin is easily calculated by using BPA software. There are other longer, mathematical methods of determining the area or origin, one of which is the tangential method.

IABPA definition:

- Point (Area) of Origin - The common point (area) in three-dimensional space to which the trajectories of several blood drops can be retraced. (see figure 5)

Once the angle of impact and the point and or area of convergence are identified, there are techniques that can be used to find where the bloodshed most likely occurred. The most basic and longest applied technique is the string method. A blood spatter analyst positions their protractor at the location of the blood stain and projects a string at the angle of impact in the direction of the point or area of convergence. This will predict a general origin of the blood loss. Another technique applicable is the trigonometric method, which is fairly similar to the string method. Since we know the point of convergence, we can measure the distance from the blood stain to that point. With this measurement along with the angle of impact, we can use basic trigonometric rules to solve for where in space the origin of blood shed is. By taking the tangent of the angle of impact and multiplying by the distance from the point of convergence, we can find the approximate height of the origin.[5]

Photography

Crime scene photography has some unique requirements. When there is a bloodletting scene, the basics are still required but special attention must be given to the bloodstains. The current means of documenting the scene include 35 mm (B&W, colour, and specialty film), digital cameras, and video (Hi-8, DV, and other formats). Each method has its pros and cons. Often the scene is documented using multiple methods. (Videography has been included here because it follows the same principles and provides crime scene images.)

There are three types of crime scene photos:

- Overall – wide-angle images (28–35 mm range) that capture the scene as it is. This type of image provides anyone who has not been in the scene a good overall layout.

- Mid-range – images taken with a normal lens (45–55 mm range) give greater detail than the overall shots. In the case of a bloodletting scene, the mid-range image could capture a single bloodstain pattern.

- Close-up – images taken with a macro lens giving the greatest amount of detail. For example, a medium velocity impact pattern can contain thousands of individual stains where there is a preponderance of small stains (1–3 mm in diameter) some of which require individual images.

Many times an analyst cannot attend a bloodletting scene, and must work from the crime scene images and notes of the person who attended. An appropriate sized scale should be in overall, mid-range, and close-up images. For overall images the scales should be parallel and perpendicular to the floor. This provides the analyst, and anyone else who looks at the images, a proper perspective on what they are observing. (Note: in some cases overall and mid-range images are taken with and without a scale.)

Reliability

While bloodstain pattern analysis has a solid foundation in science and can be a useful tool for investigators, the reliability of courtroom testimony by bloodstain pattern analysts has come under fire in recent years. Care needs to be taken to ensure that the bloodstain pattern analyst has appropriate credentials and training as well as uses appropriate methods. Even with proper training and methods, there are still many times where reputable analysts disagree on their findings, which calls into question the reliability of their conclusions and its value as evidence in court.[1]

In the criminal case against David Camm, who was tried three times for the murder of his family largely on the basis of blood spatter evidence, both prosecution and the defense used expert bloodstain pattern analysts to interpret the source of the approximately 8 drops of blood on his shirt. The prosecution's experts included Tom Bevel and Rod Englert, who testified that the stains were high velocity impact spatter. Paul Kish, Barton Epstein, Paulette Sutton, Barrie Goetz and Stuart H. James testified for the defense that the stains were transferred from his shirt brushing against his daughter's hair.[6] Dr. Robert Shaler, Founding Director of the Penn State Forensic Science Program, decried blood spatter analysis as unreliable in the Camm case. "The problem in this case is the number of stains are minimal," he said. "I think you're really on the edge of reliability." All of the blood spatter analysts involved in the case are "experts" in the traditional sense. The problem is "We have two opinions in this case. That, in essence, is a 50 percent error rate." An unacceptable level of reliability in a court case when the perception of guilt beyond a reasonable doubt is what is required.[7]

Further complicating matters was the testimony of Rob Stites. Stites testified for the prosecution that he was an expert blood spatter analyst. It was later uncovered that he had no training and his credentials were fabrications by the prosecutor. His testimony that the blood on Camm's shirt was high velocity impact spatter aided in the conviction of David Camm. Dr. Shaler pointed out that one limitation of blood spatter analysis testimony is that "you do not have the supporting underlying science" to back up your conclusions. When Stites testified, the jury had no way of knowing that he was not the expert that he purported to be. Even among the expert witnesses, it is unknown which set of experts interpreted the stains accurately as there is no objective way of determining which bloodstain pattern analyst has applied the science correctly.[8]

Other times, bloodstain patterns from different causes can mimic each other. In the 2008 trial of Travis Stay for the murder of Joel Lovelien, prosecution witness Terry Laber testified that the blood spatter on Stay's clothing came from blows to Lovelien during a fist fight. After a review of the evidence by Paul Kish, another bloodstain pattern analyst, Laber reviewed the report submitted by Kish and revised his findings to include the possibility that the blood came from expiration by Lovelien.[9]

In popular culture

- Sam Tyler, the time-travelling detective in episode 3 of the Emmy Award-winning BBC TV series Life on Mars, asks his colleague Chris Skelton to make a blood pattern analysis, quickly realizing by his puzzled expression that in 1973 such techniques are not known.

- Serial killer Dexter Morgan of the Dexter novels and Showtime series is a blood spatter analyst for the fictitious Miami Metro Police Department.

- Julie Finlay is a blood spatter analyst on the CBS series CSI: Crime Scene Investigation.

References

- 1 2 Moore, Solomon (February 4, 2009). "Science found wanting in nation's crime labs". New York Times.

- ↑ Eduard Piotrowski, Ueber Entstehung, Form, Richtung und Ausbreitung der Blutspuren nach Hiebwunden des Kopfes [On the formation, form, direction, and spreading of blood stains after blunt trauma to the head] (Vienna, Austria: 1895).

- 1 2 Brodbeck, Silke (2012). "Introduction to bloodstain pattern analysis" (PDF). Journal for Police Science and Practice. 2: 51–57. doi:10.7396/IE_2012_E.

- ↑ Snyder, LeMoyne (1971). Homicide Investigation: Practical Information for Coroners, Police Officers, and Other Investigators. Charles C. Thompson Publishers, 3rd Edition

- ↑ James, Stuart (2005). Principles of Bloodstain Pattern Analysis: Theory and Practice. Boca Raton, FL: CRC

- ↑ Kozarovich, Lisa Hurt. "Blood Spatter Evidence Not an exact Science". News and Tribune. Retrieved 8 February 2014.

- ↑ Kircher, Travis. "David Camm blogsite: Our own little experiment". WDRB. Retrieved January 1, 2014.

- ↑ Kircher, Travis. "David Camm blogsite: Uncle Sam". WDRB. Retrieved January 1, 2014.

- ↑ ingersoll, archie (December 23, 2008). "Jury finds Princeton man not guilty of murder". The Grand Forks Herald.

Additional sources

- Bevel, Tom; Gardner, Ross M. Bloodstain Pattern Analysis With an Introduction to Crimescene Reconstruction, 3rd Ed. CRC Press 2008

- James, Stuart H.; Kish, Paul Erwin; Sutton, T. Paulette (2005). Principles of Bloodstain Pattern Analysis (3rd, illustrated, revised ed.). Taylor and Francis/CRC Press. ISBN 0-8493-2014-3. Retrieved 2009-01-30.

- Hueske, Edward E., Shooting Incident Investigation/Reconstruction Training Manual, 2002

- IABPA (International Association of Bloodstain Pattern Analysts). Suggested IABPA Terminology List. Retrieved October 2005 from: http://www.iabpa.org/Terminology.pdf

- IABPA (International Association of Bloodstain Pattern Analysts). Suggested IABPA Terminology List. Retrieved October 2005 from: http://www.iabpa.org/RevEduc.pdf

- Bremmer et al., Biphasic Oxidation of Oxyhemoglobin in Bloodstains. Plos One 2011. http://plosone.org/article/info:doi/10.1371/journal.pone.0021845

- James, Stuart H, Eckert, William G. Interpretation of Bloodstain Evidence at Crime Scenes, 2nd Edition, CRC Press 1999.

- Solomon, Berg, Martin, & Villee. Biology, 3rd edition. Saunders College Publishing, Fort Worth, 1993.

- Sutton, Paulette T., Bloodstain Pattern Interpretation, Short Course Manual, University of Tennessee, Memphis TN 1998

- Vennard, John King. Elementary fluid mechanics. John Wiley & Sons, New York, 1982.

External links

- FBI Laboratory Scientific Working Group on Bloodstain Pattern Analysis (SWGSTAIN)

- International Association of Bloodstain Pattern Analysts (IABPA)

- Association for Crime Scene Reconstruction

- Bloodstain Pattern Analysis Terminology - SWGSTAIN terminology with examples

- Bloodstain Pattern Analysis Research - database of BPA-related research articles