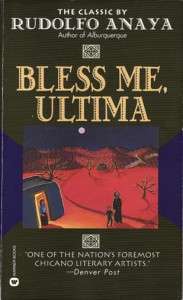

Bless Me, Ultima

Cover of the April 1994 printing | |

| Author | Rudolfo Anaya |

|---|---|

| Cover artist | Bernadette Vigil and Diane Luger |

| Country | US |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Coming of age |

| Publisher | TQS Publications |

Publication date | 1972 |

| Media type | hardback/paperback |

| Pages | 262 |

| ISBN | 0-446-60025-3 |

| OCLC | 30095424 |

| Followed by | Heart of Aztlan |

Bless Me, Ultima is a novel by Rudolfo Anaya in which his young protagonist, Antonio Márez y Luna, tells the story of his coming-of-age with the guidance of his curandera, mentor, and protector, Ultima. It has become the most widely read and critically acclaimed novel in the Chicano literary canon since its first publication in 1972.[1][2][3] Teachers across disciplines in middle schools, high schools and universities have adopted it as a way to implement multicultural literature in their classes.[4][5] The novel reflects Chicano culture of the 1940s in rural New Mexico. Anaya’s use of Spanish, mystical depiction of the New Mexican landscape, use of cultural motifs such as La Llorona, and recounting of curandera folkways such as the gathering of medicinal herbs, gives readers a sense of the influence of indigenous cultural ways that are both authentic and distinct from the mainstream.

Bless Me, Ultima is Anaya's best known work and was awarded the prestigious Premio Quinto Sol. In 2008, it was one of 12 classic American novels [lower-alpha 1] selected for The Big Read, a community-reading program sponsored by the National Endowment for the Arts,[7] and in 2009, it was the selected novel of the United States Academic Decathlon.

Bless Me, Ultima is the first in a trilogy followed by the publication of Heart of Aztlan (1976) and Tortuga (1979). With the publication of his novel, Alburquerque (1992), Newsweek proclaimed Anaya a front-runner in "what is better called not the new multicultural writing, but the new American writing."[2]

Because Bless Me, Ultima contains adult language, and because some of the content is violent and contains sexual references, it has been included in the list of most commonly challenged books in the U.S. in 2013.[8] Those characteristics notwithstanding it is also important because it was one of four novels published in the last third of the twentieth century which gained academic respect for Chicano literature as an important and nonderivative type of American literature.[lower-alpha 2]

Creation and purpose as an autobiography

Bringing Bless Me, Ultima to fruition took Anaya six years. It took an additional two years to find a publisher. From 1965 to 1971,[11] he struggled to find his own "voice" as the literary models he knew and had studied at the University of New Mexico (BA English, 1963) did not fit him as a writer. He has also remarked on the unavailability of any authors at that time who could serve as mentors for his life experience as a Chicano.[12] Anaya says that the great breakthrough in finding his voice as a writer occurred in an evening when he was writing late at night. He was struggling to find a way to get the novel to come together and then:

I felt something behind me and I turned and there is this old woman dressed in black and she asked me what I am doing. ' Well I'm trying to write about my childhood, you know, about growing up in that small town.' And she said, ' Well, you will never get it right until you put me in it.' I said, ' well who are you? ' and she said, ' Ultima'.[12]

This was the epiphany that Anaya believes came from his subconscious to provide him a mentor and his spiritual guide to the world of his Native American experience (115).[13]

In Anaya's first novel his life becomes the model for expressing the complex process of growing up Chicano in the American Southwest. Michael Fink characterizes Anaya's work as "the search for a sense of place."[14] And the author tells us,"Bless Me, Ultima takes place in a small town in eastern New Mexico and it is really the setting of my home town Santa Rosa, New Mexico. Many of the characters that appear are my childhood friends."[12]

The autobiographical relationship between Anaya and his first novel best begins through the author's own words as he reflects on his life's work as an artist and as a Chicano:

What I've wanted to do is compose the Chicano worldview — the synthesis that shows our true mestizo identity — and clarify it for my community and myself. Writing for me is a way of knowledge, and what I find illuminates my life.[15]

Anaya's authenticity to speak about the Chicano worldview is grounded in the history of his family. He is descended from among those Hispanos who originally settled the land grant in Albuquerque called "La Merced de Atrisco" in the Rio Grande Valley (2).[16] Anaya chooses Maria Luna de Márez as the name of Antonio's mother which parallels his own mother's surname, and her cultural and geographical origins: Rafaelita Mares, the daughter of farmers from a small village near Santa Rosa called Puerto De Luna.[16] In additional ways Anaya's family and that of his young protagonist parallel: Both Rafaelita's first and second husbands were vaqueros (cowboys) who preferred life riding horses, herding cattle and roaming the llano, as did Antonio's father, Gabriel. Anaya's family also included two older brothers who left to fight WW II and four sisters. Thus, Anaya grew up in a family constellation similar to that of his young protagonist. Anaya's life and that of Antonio parallel in other ways that ground the conflict with which his young protagonist struggles in advancing to adolescence. As a small child Anaya moved with his family from Las Pasturas, his relatively isolated birthplace on the llano to Santa Rosa a "city" by New Mexico standards of the time. This move plays a large part in the first chapter of Anaya's first novel as it sets the stage for Antonio's father's great disappointment in losing the lifestyle of the llano that he loved so well, and perhaps the kindling of his dream to embark on a new adventure to move with his sons to California—a dream that never would be.[14]

Historical Context

Bless Me, Ultima focuses on a young boy's spiritual transformation amidst cultural and societal changes in the American Southwest during World War II. Anaya's work aims to reflect the uniqueness of the Chicano experience in the context of modernization in New Mexico—a place bearing the memory of European and indigenous cultures in contact spanning nearly half a millennium. The relationship between Anaya's protagonist, Antonio and his spiritual guide, Ultima, unfolds in an enchanted landscape that accommodates cultural, religious, moral and epistemological contradictions: Márez vs. Luna, the Golden Carp vs. the Christian God, good vs. evil, Ultima's way of knowing vs. the Church's or the school's way of knowing.[17]

"These contradictions reflect political conquest and colonization that in the first instance put the Hispano-European ways of thinking, believing, and doing in the power position relative to those of the indigenous peoples." (188)[17] New Mexico experienced a second wave of European influence—this time English speaking—which was definitively marked by U.S. victory in the war between the United States and Mexico that ended with The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in 1848. According to Richard Griswold del Castillo, "The treaty established a pattern of political and military inequality between the two countries, and this lopsided relationship has stalked Mexican-U.S relations ever since."[18]

Hispanos emigrated from Mexico to what was then one of the outermost frontiers of New Spain after Coronado in 1540 led 1100 men[19] and 1600 pack and food animals northward in search of the legendary Seven Cities of Cibola.[lower-alpha 3]

Thereafter, the Spanish built permanent communities for the Indians along the Rio Grande and introduced domesticated animals to the area, all while striving for religious conversion of the native communities. The Spanish subjugated the native people to build mission churches in each of the new villages, but the Pueblo Indians finally rebelled in 1680 and drove the Spanish out of their land.

In 1692, the Spanish, led by Don Diego de Vargas, reconquered New Mexico. This time colonizers were able to coexist with the Pueblo Indians. The Spanish established many communities in which Catholicism and the Spanish language combined with the culture and myths of the Pueblo Indians. New Mexico gained independence from Spain in 1821 and eventually achieved independent statehood in the United States of America in 1912. The mixed cultural influences and a long history of intermarriage among the Hispanos and the indigenous peoples (i.e.,the mestizaje) remained largely intact throughout rural New Mexico well into the 20th century. The colonization of New Mexico by Spanish colonists resulted, therefore, in a combination of indigenous myths with Catholicism. As the Hispano community's beliefs and ways of doing things interacted with those of the Native Americans a cultural pattern where indigenous myth maintained importance alongside Catholic doctrine evolved.

As modernization spread across the United States with completion of the transcontinental railway in the 1860s and establishment of the Rural Electrification Administration in the 1930s, isolated rural communities were changed forever.[21] The Second World War in the 1940s also wrought change as young men were sent to far off places and returned to their homeland bearing the vestiges of violent, traumatic experiences and exposure to a cosmopolitan world.

Because of the horrors that Antonio's brothers experienced in the war, none of them are able to integrate themselves back into the quiet life of Guadalupe; Antonio describes them as “dying giants” because they can no longer cope with the life that they left behind when they went to war. Their decision to leave Guadalupe is indirectly linked to their experiences in the war. The impact of modernization and war, therefore, did not exclude the Hispanos and indigenous peoples of New Mexico as the boundaries of their previously insular communities were crossed by these external technological and cultural influences.

Anaya dramatizes the pressures of change in the New Mexican peoples' response to the detonation of the first atomic test bomb near Alamogordo, New Mexico July 16, 1945 as apocalyptic:

' The atomic bomb,' they whispered, ' a ball of white heat beyond the imagination, beyond hell--' And they pointed south, beyond the green valley of El Puerto.' Man was not made to know so much,' the old ladies cried in hushed, hoarse voices, ' they compete with God, they disturb the seasons, they seek to know more than God Himself. In the end that knowledge they seek will destroy us all--.' (Anaya, p. 183) as quoted in Tonn[3]

Tonn reminds us that both the narrated time and the moment of the Novel's first appearance were periods of transition.[3] The United States in the decades of the 1960s and 70's underwent a series of deep societal changes which some scholars deem as apocalyptic to U.S. society as the detonation of the Atomic bomb was to the New Mexican peoples in 1945. Berger(2000:388),cited in Keyword:Apocalypse,[22] outlines two additional areas of post war apocalyptic representation after (1) nuclear war, and (2)the Holocaust. They are (3) apocalypses of liberation (feminist, African American, postcolonial) and (4) what is loosely called "postmodernity".

Anaya's writing of Bless, Me Ultima coincided with one of the principal upheavals of the move toward liberation, the Civil Rights movement including the Chicano farm labor movement led by Cesar Chavez. Tonn points out that events surrounding the struggle for civil rights, the Vietnam War, the assassinations of John Kennedy and Martin Luther King, urban disturbances such as Watts and Detroit posed deep-seated "challenges to the dominant self-image of United States Society. . . ." "[. . .]leading to fundamental shifts in societal values and mores."[3]

Tonn and Robert Cantú[23] challenge the received consensus on the purpose of the novel and its relation to its past historical reality.

Plot summary

Set in the small town of Guadalupe, New Mexico just after World War II,[16] Antonio Márez y Luna (Tony) tells his story from the memories of his adult self, who reflects on his growing up. Anaya uses the basic structure of the Bildungsroman to weave a tale from the child's point of view of good and evil, of life and death, of myth and reality that challenges young Tony's beliefs about God, his family and his destiny. His progress in learning about life is grounded in Ultima, an aged and wise member of the community who is highly respected by Tony's parents. Tony has a very special relationship with her, as she was the midwife at his birth. Throughout the story she passes on her wisdom and knowledge to Tony.

The novel begins as Tony's parents, Gabriel and Maria, invite Ultima to come and live with them when Tony is about to turn seven—just reaching the age of reason. As Tony, with Ultima's guidance, searches for his true identity and his rightful destiny, he witnesses several deaths, assists Ultima in purging his uncle Lucas of an evil spell, experiences a crisis of faith in the Catholic tradition, embraces the myth of the golden carp, discovers the sordidness of his older brother, survives a harrowing illness and realizes that he may be the only heir to the cultural and spiritual legacy that was Ultima, for Ultima is the last of her kind.

Throughout the novel Tony struggles with his identity. In the first chapter Anaya establishes the roots of this struggle through Tony's dream—a flashback to the day of his birth. In his dream Tony views the differences between his parents' familial backgrounds. His father's side, the Márez (descendents of the sea), are the restless vaqueros who roam the llanos and seek adventure. The Lunas, his mother's side, are the people of the moon, religious farmers whose destiny is to homestead and work the land. Each side of the family wants control of the newborn's future. But, as the dream ends, Ultima intercedes and takes on the responsibility for knowing and guarding Tony's destiny herself. His mother's dream is for him to become a Roman Catholic priest, His father's dream is to embark on a new adventure and move west to California with his sons to recapture the openness of the Llano he has foregone in moving to the town.

Early on Antonio must come to grips with the opposition between good and evil. Ultima, in her role as protector, uses her knowledge of healing and magic to neutralize the evil witchcraft the three daughters of Tenorio Trementina have wrought on Tony's uncle, and toward the end her soul struggles against the evil of Tenorio himself.

Over the course of the novel Antonio becomes disillusioned with the faith and through Cico, one of his closer friends learns of another god. Throughout the novel Tony keeps trying to reconcile the complexity of his mixed familial heritage Lunas with the Márez,and his mixed religious heritage: traditional Catholicism with the Native American religion.

Early on Tony's experience preparing for and making his First Communion, the second rite of passage of the Catholic Church, leaves him disillusioned as he did not receive the spiritual knowledge he had expected. He begins to question the value of the Catholic Church, concentrated on the Virgin Mary and a Father God, and on ritual, as unable to answer his moral and metaphysical dilemmas. At the same time, realizing that the Church represents the female values of his mother, Tony cannot bring himself to accept the lawlessness, violence and unthinking sensuality which his father and older brothers symbolize. Instead through his relationship with Ultima, he discovers a oneness with nature.[24] Through his discovery that "All is One" he is able to resolve the major existential conflict in his life.

At the conclusion of the novel, Antonio reflects on the tension that he feels as he is pulled between his father's free, open landscape of the llano, and his mother's circumscribed river valley of the town. In addition, he reflects on the pull between Catholicism and Ultima's way of life and concludes that he does not need to choose one over the other, but can bring both together to form a new identity and a new religion that is made up of both. Antonio says to his father:

Take the llano and the river valley, the moon and the sea, God and the golden carp—and make something new... Papa, can a new religion be made?[25]

Characters

Antonio Juan Márez y Luna – Antonio is 7 and very serious, thoughtful, and prone to moral questioning, and his experiences force him to confront difficult issues that blur the lines between right and wrong. He turns to both pagan and Christian ideologies for guidance, but he doubts both traditions. With Ultima’s help, Antonio makes the transition from childhood to adolescence and begins to make his own choices and to accept responsibility for their consequences.

Gabriel Márez and Maria Luna – Tony's parents. Both hold conflicting views about Tony's destiny and battle over his future path. While Gabriel represents the roaming life of a vaquero and hopes for Tony to follow this path of life, Maria represents the settled life of hard-working farmers and aspires for her son to become a priest.

Ultima – An elderly curandera, known in the Márez household as "La Grande" is the embodiment of the wisdom of her ancestors and carries within her the powers to heal, to confront evil, to use the power of nature and to understand the relationship between the seen and unseen. Her role in the community is as mediator. "She preserves the indispensable contact with the world of nature and the supernatural forces inhabiting this universe (255)."[26] She is the spiritual guide for Antonio as he journeys through childhood. Ultima knows the ways of the Catholic Church and also the ways of the indigenous spiritual practices over which she is master. Ultima understands the philosophy and the morality of the ancient peoples of New Mexico and teaches Tony through example, experience and critical reflection, the universal principles that explain and sustain life. Although she is generally respected in the community, people sometimes misunderstand her power. At times she is referred to as a bruja, or witch, but no one—not even Antonio—knows whether or not she is truly a witch. Finally Antonio puts pieces of the puzzle together and the revelation of who she is comes to him. She holds Antonio's destiny in her hands, and at the end of the story sacrifices her own life so that Antonio might live.

Tenorio Trementina and his three daughters – Tenorio is a malicious saloon-keeper and barber in El Puerto. His three daughters perform a black mass and place a curse on Antonio's uncle Lucas Luna. Tenorio detests Ultima because she lifts the curse on Lucas and soon after she does so, one of Tenorio’s daughters dies. Hot-tempered and vengeful, Tenorio spends the rest of the novel plotting Ultima’s death, which he finally achieves by killing her owl familiar, her spiritual guardian. Afterwards, he tries to kill Antonio but is shot by Uncle Pedro.

Ultima's Owl – Embodies Ultima's soul, the power of her mysticism, and her life force. The song the owl sings softly outside Antonio’s window at night indicates Ultima’s presence and magical protection in Antonio’s life. Ultima's owl scratches Tenorio's eye out as he stands in Gabriel's doorway and demands the right to take Ultima away from Gabriel's house. By the end of the novel Tenorio has figured out the connection between Ultima and her owl. By killing Ultima's owl, Tenorio destroys Ultima’s soul and life force, which leads quickly to her death. Antonio takes on the responsibility of burying the owl and realizes that he is really burying Ultima.

Lupito – A war veteran who has post-traumatic stress disorder. After Lupito murders the local sheriff in one of his deranged moments, he is killed by the sheriff and his posse as young Antonio looks on from his hiding place on the banks of the river. Lupito’s violent death provides the catalyst for Antonio’s serious moral and religious questioning.

"Lucas Luna" – Antonio's uncle, who gets cursed by the Trementina sisters when he tries to stop them from practicing black magic. As a result, he gets so sick that Ultima is summoned to cure him. She concocts a potient of herbs, water, and kerosene as a purgative and uses Antonio's innocence as a mediator to effect the cure.

Narciso – Although known as the town drunk, Narciso cuts a large, strong figure of a man. Narciso and Gabriel are good friends because they share a deep and passionate love for the llano. Narciso has a deep abiding loyalty and love for Ultima because of her extraordinary efforts to save his young wife who had succumbed to an epidemic that struck the town. Narciso demonstrates a strong appreciation for the richness of the earth —his garden is a lush masterpiece full of sweet vegetables and fruits. Tenorio kills him as he is on his way to warn Ultima that Tenorio is after her. As he lies dying in Antonio's arms, he asks Antonio to give him a blessing.

Téllez – One of Gabriel’s friends. He challenges Tenorio when Tenorio speaks badly of Ultima. Not long afterward, a curse is laid on his home. Ultima agrees to lift the curse, explaining that Téllez’s grandfather once hanged three Comanche Indians for raiding his flocks. Ultima performs a Comanche funeral ceremony on Téllez’s land, and ghosts cease to haunt his home.

Antonio’s friends: Abel, Bones, Ernie, Horse, Lloyd, Red, and the Vitamin Kid – An exuberant group of boys who frequently curse and fight. Horse loves to wrestle, but everyone fears Bones more because he is reckless and perhaps even crazy. Ernie is a braggart who frequently teases Antonio. The Vitamin Kid is the fastest runner in Guadalupe. Red is a Protestant, so he is often teased by the other boys. Lloyd enjoys reminding everyone that they can be sued for even the most minor offenses. Abel, the smallest boy in the group, frequently urinates in inappropriate places.

Samuel – One of Antonio’s friends. He is also the Vitamin Kid’s brother. Unlike most of Antonio’s friends, Samuel is gentle and quiet. He tells Antonio about the golden carp. It is here that Antonio starts questioning his faith.

Florence – One of Antonio's friends who does not believe in God, but goes to catechism to be with his friends. Florence shows Antonio that the Catholic Church is not perfect. He dies in a very bad drowning accident.

Jasón Chávez – One of Antonio’s friends. He disobeys his father when he continues to visit an Indian who lives near the town. He is described by Antonio as being moody.

Jasón Chávez’s Indian – A friend of Jasón’s who is disliked by Jasón’s father. Cico tells Antonio that the story of the golden carp originally comes from the Indian.

Andrew, Eugene, and León Márez – Antonio’s brothers. For most of Antonio’s childhood, his brothers are fighting in World War II. When they return home, they suffer post-traumatic stress as a result of the war. Restless and depressed, they all eventually leave home to pursue independent lives, crushing Gabriel’s dream of moving his family to California.

Deborah and Theresa Márez – Antonio’s older sisters. Most of the time, they play with dolls and speak English, a language Antonio does not begin to learn until he attends school.

Antonio’s uncles – Juan, Lucas, Mateo, and Pedro Luna – María’s brothers are farmers. They struggle with Gabriel to lay a claim to Antonio’s future. They want him to become a farmer or a priest, but Gabriel wants Antonio to be a vaquero in the Márez tradition. Antonio’s uncles are quiet and gentle, and they plant their crops by the cycle of the moon.

Father Byrnes – A stern Catholic priest with hypocritical and unfair policies. He teaches catechism to Antonio and his friends. He punishes Florence for the smallest offenses because Florence challenges the Catholic orthodoxy, but he fails to notice, and perhaps even ignores, the misbehavior of the other boys. Rather than teach the children to understand God, he teaches them to fear God.

Chávez – Chávez is the father of Antonio’s friend Jasón. Distraught and vengeful, he leads a mob to find Lupito after Lupito kills Chávez’s brother, the local sheriff. He forbids Jasón to visit an Indian who lives near the town, but Jasón disobeys him.

Prudencio Luna – The father of María and her brothers. He is a quiet man who prefers not to become involved in other peoples’ conflicts. When Tenorio declares an all out war against Ultima, he does not want his sons to get involved, even though Ultima saved Lucas’s life.

Miss Maestas – Antonio’s first-grade teacher. Although Antonio does not speak English well, Miss Maestas recognizes his bright spark of intelligence. Under her tutelage, Antonio unlocks the secrets of words. She promotes him to the third grade at the end of the year.

Miss Violet – Antonio's third grade teacher. He, with Abel, Bones, Ernie, Horse, Lloyd, Red, and the Vitamin Kid, set up a play about the First Christmas on a dark and snowy night, which turns into a hilarious disaster because of the ever crazy Bones.

Rosie – The woman who runs the local brothel. Antonio has a deep fear of the brothel because it represents sin. He is devastated when he finds out that his brother Andrew frequently goes to it.

The flying man – This man was Ultima’s teacher and was also known as el hombre volador. He gave her the owl that became her spirit familiar, her guardian, and her soul. He told her to do good works with her powers, but to avoid interfering with a person’s destiny. The invocation of his name inspires awe and respect among the people who have heard about his legendary powers and incites fear in Tenorio Trementina.

Literary Interpretations

Development of an American Mestizaje, Antonio's Boon

After the Mexican Revolution of 1910, the state officially constructed a Mexican national identity policy on the proposition that Mexicans are the product of a creative mixing of Indians and Europeans—that is, about a fusing together of cultures. This doctrine is expressed in official rhetoric, mythology and public ceremonial. In practice, however, the emphasis on culture gets conflated with the biological mixing of races, mestizaje in Spanish. The Revolution's goals included returning to Mexico's indigenous peoples their dignity as full-fledged citizens by relieving them from a history of exploitation, providing them with material progress and social justice. In return for this, Mexican Indians would give up their old customs, speak Spanish and join the mainstream of national life, defined as mestizo, the biological issue of mixed-race parentage. Thus, the Mexican "Mestizaje" has come to represent a policy of cultural assimilation.[27]

A number of Anaya critics and at least one Chicana novelist view his young protagonist's path to adolescence as a spiritual search for a personal identity. The result embodies the synergistic integration of both the cultural and biological aspects of his indigenous and European inheritances as the creation of something new.[3][10][14][16][17][28][29] Antonio's successful quest provides the world with a new model of cultural identity —a new American Mestizaje for the American Mestizo known as the Chicano. This model repudiates assimilation to the mainstream culture, but embraces acceptance of our historical selves through creative adaptation to the changing world around us.

Margarite Fernandez Olmos comments on the novel's pioneering position in the Chicano literary tradition: "Bless Me, Ultima blazed a path within the Chicano literary tradition in the [genre] novels of identity in which the main characters must redefine themselves within the larger society from the vantage point of their own distinct ethnicity." (17)[16] Others, such as Denise Chavez (Face of an Angel,1994) support Olmos' position. In an interview with Margot Kelly, Chavez concludes, "Anaya maintains that the kind of protagonist who will be able to become free is a person of synthesis, a person who is able to draw . . .on our Spanish roots and our native indigenous roots and become a new person, become that Mestizo with a unique perspective."[28] In general, Amy Barrias' analyses of representative coming-of-age Chicano and American Indian texts, including Bless Me, Ultima allows her to conclude that because American Indian and Chicano(a) writers find very little in dominant culture on which to build an identity, they have turned inward to create their own texts of rediscovery. (16)[10]

Michael Fink uses a wider lens to suggest that Anaya's seminal novel is a contribution to identity and memory politics that provides us with "a set of strategies of transcultural survival . . .[in which] former collective identities are eventually transformed into new hybrid identities of difference." (6–7)[14]

Anaya uses strategies that employ the need for a mentor, and the return to ancient spiritual roots encompassing belief in magic, mysticism, and the shaman's trance. Fernandez Olmos remarks on mentorship: "In Bless Me, Ultima the figure of Ultima . . . is crucial. As young Antonio's guide and mentor, her teachings not only bring him into contact with a mystical, primordial world but also with a culture —his own Hispanic/Indian culture— that he must learn to appreciate if he is ever to truly understand himself and his place within society." (17)[16] Amy Barrias cites the novel as a prime example of the use of magical intervention as the mediator, which enables Antonio to "emerge from his conflicts with a blended sense of identity. [He takes] the best each culture has to offer to form a new perspective."(iv)[10]

Cynthia Darche Park focuses on the shaman's initiation [lower-alpha 4] as the spiritual experience that allows Antonio's transcendental integration of the conflicts with which he is struggling:

Through all that has transpired between them Antonio is ready near the end of his journey with Ultima to descend into the vast underworld, the great void of the unconscious where there are no divisions —neither of body and soul, nor time and space, nor matter and spirit. (194)[17]

Anaya as Mythmaker: Apocalypse as Revelation, The Hero's Journey,

The mythos of any community is the bearer of something which exceeds its own frontiers; it is the bearer of other possible worlds...It is in this horizon of the ‘possible’ that we discover the universal dimensions of symbolic and poetic language.

– Paul Ricoeur

Robert Cantú suggests that apocalypse as revelation is the ideological construct that best explains the novel's structure and purpose. His reconstructive analysis shows how Antonio, as narrator, solves and resolves his troubling metaphysical questions through a series of revelations mediated by Ultima and her otherworldly connections. As more and more is revealed to Tony, a transcendent reality is disclosed which is both temporal, insofar as it envisages eschatological salvation; and spatial, insofar as it involves another, supernatural world.[31]

An ideology is a set of ideas that constitute one's goals, expectations, and actions. An ideology can be thought of as a comprehensive vision, as a way of looking at things (compare worldview), as in several philosophical tendencies (see Political ideologies), or a set of ideas proposed by the dominant class of a society to all members of this society (a "received consciousness" or product of socialization).

Myth and magic as healing

Because healing is Ultima's mission, Antonio's relationship with her includes accompanying her to gather the curative herbs she knows about through tradition and spiritual revelation. With her Antonio visits the sick and begins to grasp a connection between healing and nature even though he never receives an explicit scientific or grounded explanation for how she foretells future occurrences, heals the infirm, combats witches through casting spells, or when and why she decides not to intervene. Ultima's indigenous and experiential pedagogy allows Antonio to intuit that her approach to healing includes a sense of who the afflicted person is, what s/he believes, knowledge of the healing powers of her herbs, and the limits of her power.[32] He learns through assisting Ultima in the cure of his uncle that healing requires making himself vulnerable to sickness and to the spiritual as well as physical needs of the sick. With Antonio, Ultima's relationship as healer is also one of teacher. Cynthia Park considers the relationship between those two roles, and abstracts a set of life-giving principles that form the basis for Ultima's way of knowing.[17]

Reception and Legacy

As of 2012, Bless Me, Ultima has become the best-selling Chicano novel of all time. The New York Times reports that Anaya is the most widely read author in Hispanic communities, and sales of his classic, Bless Me, Ultima (1972) have surpassed 360,000.[2]

After Quinto Sol's initial publication of Bless Me, Ultima in 1972, critics by and large responded enthusiastically. The general consensus was that the novel provided Chicano literature with a new and refreshing voice.[33] Scott Wood, writing for America Press, asserted:

This is a remarkable book, worthy not only of the Premio Quinto Sol literary award. . .but [also]. . . for its communication of tender emotion and powerful spirituality ... ; for its eloquent presentation of Chicano consciousness in all its intriguing complexity; finally, for being an American novel which accomplishes a harmonious resolution, transcendent and hopeful.[34]

By 1976, four years after Bless Me Ultima's initial publication, the new author was finding fans and fame among Chicano readers and scholars. He was in high demand as a speaker and the subject of numerous interviews primarily among journalists and publicists who were Chicanos or deeply interested in the development of Chicano literature. In the preface to his 1976 interview with Anaya reprinted in Conversations with Rudolfo Anaya (1998), Ishmael Reed states that, Bless Me Ultima, as of July 1, 1976, had sold 80,000 copies without a review in the major media.[35]

For twenty-two years after the novel's initial publication (its only availability through a small publisher notwithstanding), the novel sold 300,000 copies primarily through word of mouth.[36] In this period the novel generated the largest body of review, interpretation, and analysis of any work of Chicano Literature (p. 1).[3] Finally in 1994, a major publisher (Grand Central Publishing) issued a mass-market edition of Bless Me, Ultima to rave reviews.

Terri Windling described the 1994 re-issue as "an important novel which beautifully melds Old World and New World folklore into a contemporary story".[37]

Censorship

After its publication in 1972, Bless Me, Ultima emerged as one of the "Top Ten Most Frequently Challenged Books" in the years 2013 and 2008.[38] According to the American Library association, a challenge is an attempt to restrict access of a book through the removal of the text in curriculum and libraries.[39] Specific reasons for the challenges in 2013 were "occult/Satanism, offensive language, religious viewpoint, sexually explicit" and similarly in 2008 of "occult/satanism, offensive language, religious viewpoint, sexually explicit, violence".[38]

A particularly visceral experience in the censorship of this book was in 1981: the Bloomfield School Board in San Juan County, New Mexico burned copies of the Bless Me, Ultima.[40]

Round Rock Independent School District (Texas)

In 1996, after appearing on advanced placement and local high school reading lists in Round Rock Independent school district, the novel came to parents attention, which according to Foerstel led to “seven hours of boisterous debate over a proposal to remove a dozen books”, one of which was Bless Me, Ultima. One of the worries of the parents was excessive violence.[41] However a local paper, The Austin American Statesman, claimed “ Refusing to allow credit for those celebrated literary works would have been an unnecessary intrusion by the school board.” After multiple hearing and proposals, the board came to a 4-2 vote against the banning of the book.[42]

Newman-Crows Landing Unified School District (California)

After a parent filed a complaint regarding Bless Me, Ultima, the novel was withdrawn from the classroom, which affected the 200 students of whom were expected to read it over the course of the year. The parent who made the original complaint argued that the text used explicit wording and anti-Catholic views “that undermine the conservative family values in our homes.”[43] However, one attendee of the special meeting noted in favor of the book that "I can't think of a book, I can't think of a newspaper article that's not offensive to some people."[43] Ultimately, the board trustees voted 4-1 to remove Bless Me, Ultima from the curriculum however the novel will continue to remain in the library.[44]

Theatrical adaptation

On April 10 and 12, 2008, in partnership with The National Endowment for the Arts' Big Read, Roberto Cantú, professor of Chicano Studies and English, who is intimately familiar with Bless Me, Ultima, produced a dramatic reading as a stage adaptation of the novel at Cal State L.A. Cantú first reviewed the work when it was published in 1972, and has published and lectured extensively on its art, structure, and significance. The production featured veteran television and film actress Alejandra Flores (A Walk in the Clouds, Friends with Money) as Ultima. Theresa Larkin, a theatre arts professor at Cal State L.A., adapted and directed it.[45]

Also in partnership with The Big Read program, Denver, Colorado's premier Chicano theater company, El Centro Su Teatro, produced a full length workshop stage production of Bless Me, Ultima, for which Anaya himself wrote the adaptation. The play opened on February 12, 2009, at El Centro Su Teatro, directed by Jennifer McCray Rinn,[46] with the title roles of Ultima played by Yolanda Ortega,[47] Antonio Márez by Carlo Rincón, and The Author by Jose Aguila.[48] An encore production was done at The Shadow Theater in Denver on June 26 and 27, 2009, with the title roles of Ultima played by Yolanda Ortega, Antonio Marez by Isabelle Fries, and The Author by Jose Aguila.

The Vortex Theatre in Albuquerque, New Mexico, in partnership with the National Hispanic Center, produced a full stage production of the show from March 26, to April 25, 2010. It was directed by Valli Marie Rivera and again adapted by the author himself.[49] Juanita Sena-Shannon played Ultima to rave reviews.[50] The Vortex Production toured through various cities in New Mexico in October and November 2010. The final performance took place on November 19, 2010.

Film adaptation

Variety reported on March 2, 2009[51] that Christy Walton, heiress to the Walton fortune, had set up Tenaja Productions company solely to finance a film adaptation of Bless Me, Ultima. Monkey Hill Films' Sarah DiLeo is billed as producer with collaboration and support from Mark Johnson (producer) of Gran Via Productions (Rain Man, Chronicles of Narnia) and Jesse B. Franklin of Monarch Pictures. Carl Franklin (One False Move, Devil in a Blue Dress, Out of Time) was tapped as a writer and director. Walton and DiLeo shared a passion for the book, and the latter had succeeded in convincing Anaya to agree to the adaptation over six years back.[52]

Shooting was scheduled in the Abiquiú area, and then resumed in Santa Fe for some interiors at Garson Studios on the Santa Fe University of Art and Design campus during the last week in October 2010.[53] Filming wrapped in Santa Fe, New Mexico in late 2010.[54] The film premiered at the Plaza Theatre in El Paso, Texas on September 17, 2012[55] and received a general release in February 2013.[56]

Notes

- ↑ The books chosen for 2008 in addition to Bless Me, Ultima by Rudolfo Anaya, included: Fahrenheit 451 by Ray Bradbury, My Antonia by Willa Cather, The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Fitzgerald, Their Eyes Were Watching God by Zora Neale Hurston, To Kill a Mockingbird by Harper Lee, and The Grapes of Wrath by John Steinbeck.[6]

- ↑ Henderson[9] establishes the definition of "nonderivative American literature"; Baria[10] makes the case for the development of a unique Native American and Chicano literary "voice" based on contemporary authors' use of the Bildungsroman including Bless Me, Ultima.

- ↑ In 1539, Friar Marcos de Niza, a Franciscan priest, reported to Spanish colonial officials in Mexico City that he’d seen the legendary city of Cibola in what is now New Mexico.[20]

- ↑ Eliade describes the near death experience of the shaman's initiation . . . [as involving a] trance-like state of consciousness containing scenarios of chaos and destruction. Each shaman views the dismemberment of his/her own body bone by bone. Then the initiate is integrated as a new being with the gnosis of the finite and the infinite, the sacred and the profane, the male and the female, the good and the evil. Every contradiction resides within. The shaman emerges through mystical ecstasy with the wondrous power to put us in touch with the perfection of the Universal Oneness.[30]

See also

- Apocalypse

- Keyword: Apocalypse

- Bildungsroman

- Bricolage

- Esotericism

- Monomyth

- Mestizo

- Our Lady of Guadalupe Also known as La Virgen de Guadalupe

- La Llorona-A Hispanic Legend retrieved December 28, 2011

- Ghostly Legends of the Southwest retrieved December 28, 2011

- The Cry, La Llorona retrieved December 28, 2011

- National Hispanic Center retrieved December 28, 2011

References

- ↑ Poey, Delia (1996). "Coming of age in the curriculum: The House on Mango Street and Bless Me, Ultima as representative texts.". The Americas. 24: 201–217.

- 1 2 3 Writing the Southwest retrieved March 31, 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Tonn, H. (1990). Bless Me, Ultima: Fictional response to times of transition. In César A. González-T. (Ed.),Rudolfo A. Anaya: Focus on Criticism. La Jolla, CA: Lalo Press.

- ↑ "So what are those kids reading?". Tribune Business News. The McClatchy Company. August 14, 2011.

- ↑ "Bless Me, Ultima – Teaching Multicultural Literature". The Expanding Canon. January 8, 2012. Retrieved April 2, 2012.

- ↑ About the Big Read Five Things. (21 September 2007). Knight Ridder Tribune Business News. Retrieved January 8, 2012, from ProQuest Newsstand. (Document ID: 1339272261).

- ↑ *The Big Read | Bless Me, Ultima

- ↑

- ↑ Henderson, C. D. (2002). Singing an American Song: Tocquevillian reflection on Willa Cather’s The Song of a Lark.In Christine Dunn Henderson (Ed.) Seers and Judges: American Literature as Political Philosophy (pp. 73–74). Lanham, Maryland: Lexington Books

- 1 2 3 4 Baria, A. G. (2000). Magic and mediation in Native American and Chicano/a literature author(s). PhD dissertation, Department of English, The Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, Baton Rouge, LA.

- ↑ Hispanic Heritage Rudolfo Anaya retrieved January 6, 2012.

- 1 2 3 Bless Me, Ultima Audio Guide – Listen! retrieved and transcribed January 2, 2012.

- ↑ Anaya, R. (1987). An American Chicano in King Arthur's Court. in Judy Nolte Lensink (Ed.), Old Southwest/New Southwest: Essays on a region and its literature, 113–118.

- 1 2 3 4 Fink, Michael (2004). Narratives of a new belonging: The politics of memory and identity in contemporary American Ethnic Literatures. Masters of Arts thesis, Institute for American Studies, University of Regensburg,Germany—Bavaria. ISBN (eBook):978-3-638-32081-8,ISBN (Book):978-3-638-70343-7.(cf. Chapter 4 " The Search for a Sense of Place").

- ↑ Clark, W. (1995, June). Rudolfo Anaya: 'The Chicano worldview'. Publishers Weekly, 242(23), 41. Retrieved January 8, 2012, from Research Library Core. (Document ID: 4465758).

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Fernández Olmos, M. (1999). Rudolfo A. Anaya: A critical companion. Westport, Conn: Greenwood Press.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Park, Cynthia Darche (2002). “Ultima: Myth, magic and mysticism in teaching and learning.” In Jose Villarino & Arturo Ramirez (Eds.), Aztlán, Chicano culture and folklore: An anthology, (3rd Edition). pp. 187–198.

- ↑ Richard Griswold del Castillo. War's End: The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo retrieved January 20, 2012.

- ↑ Biographical Notes Francisco Vazquez de Coronado retrieved January 12, 2012.

- ↑ Seven Cities of Cibola Legend Lures Conquistadors retrieved January 12, 2012.

- ↑ Florence Dean, Celebrating Electrical Power In Rural New Mexico "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2012-04-06. Retrieved 2012-01-13. retrieved January 12, 2012

- ↑ Keyword: Apocalypse

- ↑ Cantú, R. (1990). Apocalypse as an ideological construct: The storyteller’s art in Bless Me, Ultima. In César A. González-T. (Ed.), Rudolfo A. Anaya: Focus on criticism (pp. 64–99). La Jolla, CA: Lalo Press.

- ↑ Kanoza, T. M. (1999, Summer). The golden carp and Moby Dick: Rudolfo Anaya’s multi-culturalism. Melus, 24, 1–10.

- ↑ Anaya, R. A. (1972). Bless Me, Ultima. Berkeley, CA: TQS Publications.

- ↑ Cazemajou,Jean. (1990). The search for a center: The shamanic journey of mediators in Anaya's trilogy, Bless Me, Ultima; Heart of Aztlán, and Tortuga.In César A. González-T. (Ed.), Rudolfo A. Anaya: Focus on criticism (pp. 254–273). La Jolla, CA: Lalo Press.

- ↑ Mestizaje and Indigenous Identities "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2012-01-02. Retrieved 2012-03-30. retrieved March 30, 2012.

- 1 2 Kelly, Margot.(1997). A minor revolution: Chicano/a composite novels and the limits of genre. In Julie Brown (Ed.),Ethnicity and the American Short Story. (pp.63–84). Garland Publishing, Inc.: New York and London.

- ↑ Lamadrid, E. (1990). Myth as the cognitive process of popular culture in Rudolfo Anaya’s Bless Me, Ultima. In César A. González-T. (Ed.)(1990).,Rudolfo A. Anaya: Focus on criticism (pp. 100–112). La Jolla, CA: Lalo Press

- ↑ Eliade, M. (1964). Shamanism: Archaic techniques of ecstasy. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press.

- ↑ Apocalyptic Defined Archived October 14, 2012, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Literature Annotations

- ↑ Hispanic Heritage: Rudolfo Anaya retrieved January 7, 2012

- ↑ Wood, S., in Sharon R. Gunton & Jean Stine (eds), Contemporary Literary Criticism, Vol. 26, p. 22.

- ↑ Ishmael Reed (1976). "An Interview with Rudolfo Anaya", The San Francisco Review of Books. 4.2 (1978):9–12, 34. Reprinted in Dick, B., & S. Sirias (eds), (1998), Conversations with Rudolfo Anaya. 1–10. University Press of Mississippi.

- ↑ Bless Me, Ultima: Introduction retrieved January 7, 2012

- ↑ "Summation 1994: Fantasy," The Year's Best Fantasy and Horror: Eighth Annual Collection, p. xx.

- 1 2 admin (2013-03-26). "Top Ten Most Frequently Challenged Books Lists". Banned & Challenged Books. Retrieved 2016-11-07.

- ↑ "Challenges to Library Materials". American Library Association. Retrieved 2016-11-30.

- ↑ Journal, Leslie Linthicum | Of the. "Updated: New Mexico novel still fuels fears". www.abqjournal.com. Retrieved 2016-11-07.

- ↑ Foerstel, Herbet N. (2002). . Banned in the U.S.A : A Reference Guide to Book Censorship in Schools and Public Libraries. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. pp. 228, 229.

- ↑ "Austin American-Statesman". Book Ban Laid to rest. Jan 20, 1996 – via Access World News.

- 1 2 Hatfield, Michelle (Jan 6, 2009). "The Modesto Bee". Ultima Stirs Pot- Meeting on Banning Book Spurs Lively Discussion – via Access World News.

- ↑ Hatfield, Michelle (Feb 3, 2009). "The Modesto Bee". Board Upholds Novel's Removal: Bless Me Ultima Won't be Taught at Orestimba High School by 4-1 vote" – via Access World News.

- ↑ Bless Me, Ultima To Star Alejandra Flores April 10–12 as CAL State L.A. Takes Big Read From Page To Stage For Free. (2008, April 7). US Fed News Service, Including US State News. Retrieved January 8, 2012, from General Interest Module. (Document ID: 1460653401)

- ↑ Bless Me Ultima, El Centro Su Teatro Archived April 21, 2013, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Seminario Retrieved January 13, 2012

- ↑ Moore: Su Teatro proving audiences open to controversial works Retrieved January 13, 2012

- ↑

- ↑

- Before We Say Goodbye "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2012-04-26. Retrieved 2011-12-28. retrieved December 30, 2011

- ↑ Wal-Mart's Walton books film debut retrieved December 30, 2011

- ↑

- ↑ Santa Fe stars as backdrop in classic novel-turned-film 'Bless Me, Ultima' retrieved January 2, 2012

- ↑ FIND Talent Guide

- ↑ María Cortés González, "'Bless Me, Ultima' premiere in El Paso is Plaza Theatre's first in 63 years", El Paso Times, September 18, 2012.

- ↑ Ana Gershanik, "Sarah DiLeo of New Orleans produces first film, 'Bless Me, Ultima,' opening Feb. 22", Times-Picayune, February 21, 2013.

Additional Reading

- Anaya, R. A. (1972). Bless Me, Ultima. Berkeley, CA: TQS Publications.

- Baeza, A. (2001). Man of Aztlan: A Biography of Rudolfo Anaya. Waco: Eakin Press.

- Baria, A. G. (2000). Magic and mediation in Native American and Chicano/a literature author(s). PhD dissertation, Department of English, The Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, Baton Rouge, LA.

- Bauder, T. A. (1985, Spring). The triumph of white magic in Rudolfo Anaya’s Bless Me, Ultima. Mester, 14, 41–55.

- Calderón, H. (1990). Rudolfo Anaya’s Bless Me, Ultima. In César A. González-T. (Ed.), Rudolfo A. Anaya: Focus on criticism (pp. 64–99). La Jolla, CA: Lalo Press.

- Campbell, J. (1972). The Hero with a thousand faces (2nd Ed.). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Candelaria, C. (1989). Rudolfo A. Anaya. In M.J. Bruccoli, R. Layman, & C.E. Frazer Clark, Jr. (Series Eds.) and F. A. Lomelí & C. R. Shirley (Vol. Eds.), Dictionary of literary biography: Vol. 82. Chicano writers, first series (pp. 24–35). Detroit: Gale Research.

- Cantú, R. (1990). Apocalypse as an ideological construct: The storyteller’s art in Bless Me, Ultima. In César A. González-T. (Ed.), Rudolfo A. Anaya: Focus on criticism (pp. 64–99). La Jolla, CA: Lalo Press.

- Carrasco, D. (1982, Spring-Fall). A perspective for a study of religious dimensions in Chicano experience: Bless Me, Ultima as a religious text. Aztlán, 13, 195–221.

- Cazemajou,Jean. (198_). The search for a center: The shamanic journey of mediators in Anaya's trilogy, Bless Me, Ultima; Heart of Aztlán, and Tortuga.In César A. González-T. (Ed.), Rudolfo A. Anaya: Focus on criticism (pp. 254–273). La Jolla, CA: Lalo Press.

- Dasenbrock, R. W.(2002). Forms of biculturalism in Southwestern literature: The work of Rudolfo Anaya and Leslie Marmon Silko in Allan Chavkin (Ed.), Leslie Marmon Silko's Ceremony: A casebook (pp. 71–82). New York: Oxford University Press.

- Eliade, M. (1964). Shamanism: Archaic Techniques of Ecstasy. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press.

- Engstrand, I. W., Griswold del Castillo, R., Poniatowska, E., & Autry Museum of Western Heritage (1998). Culture y cultura: Consequences of the U.S.-Mexican War, 1846–1848. Los Angeles, Calif: Autry Museum of Western Heritage.

- Estes, C. P. (1992). Women who run with wolves: Myths and stories of the wild woman archetype. New York, NY: Ballantine Books.

- Fernández Olmos, M. (1999). Rudolfo A. Anaya: A critical companion.Westport, Conn: Greenwood Press.

- Fink, Michael (2004). Narratives of a new belonging: The politics of memory and identity in contemporary American ethnic literatures. Masters of Arts thesis, Institute for American Studies, University of Regensburg, Germany, Bavaria. ISBN (eBook):978-3-638-32081-8,ISBN (Book):978-3-638-70343-7.(cf. Chapter 4 "The Search for a Sense of Place").

- Gingerich, W. (1984). Aspects of prose style in three Chicano novels: Pocho, Bless Me, Ultima, and The Road to Tamazunchale" In Jacob Ornstein-Galicia (Ed.), Allan Metcalf (Bibliog.), Form and function in Chicano English (pp. 206–228). Rowley, MA: Newbury House.

- Griswold del Castillo,R.(Ed.)(2008). World War II and Mexican American civil rights. Austin: University of Texas Press.

- Griswold del Castillo,R. (1996). Aztlán reocupada: A political and cultural history since 1945: the influence of Mexico on Mexican American society in post war America. México: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Centro de Investigaciones sobre América del Norte.

- Griswold del Castillo,R. (1990). The treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo: A legacy of conflict, 1st ed. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press.

- Henderson, C. D. (2002). Singing an American Song: Tocquevillian reflection on Willa Cather’s The Song of a Lark. In Christine Dunn Henderson (Ed.) Seers and Judges: American Literature as Political Philosophy (pp. 73–74). Lanham, Maryland: Lexington Books.

- Holton, F. S. (1995, Fall). Chicano as bricoleur: Christianity and mythmaking in Rudolfo Anaya’s Bless Me, Ultima. Confluencia, 11, 22–41.

- Johnson, Elaine Dorough (1979). A thematic study of three Chicano narratives: Estampas del Valle y Otras Obras, Bless Me, Ultima and Peregrinos de Aztlan. University Microfilms International: Ann Arbor, Michigan.

- Kelly, M. (1997). A minor revolution: Chicano/a composite novels and the limits of genre. In Julie Brown (Ed.), Ethnicity and the American short story (pp. 63–84). New York and London: Garland Publishing, Inc.

- Klein, D.(1992,Sept). Coming of Age in Novels by Rudolfo Anaya and Sandra Cisneros.The English Journal, 1, 21–26.

- Kristovic, J. (Ed.) (1994). Rudolfo Anaya. In Hispanic Literature criticism (Vol.1, pp. 41–42). Detroit: Gale Research.

- Lamadrid, E. (1990). Myth as the cognitive process of popular culture in Rudolfo Anaya’s Bless Me, Ultima. In César A. González-T. (Ed.), Rudolfo A. Anaya: Focus on criticism (pp. 100–112). La Jolla, CA: Lalo Press.

- Lee, A. R. (1996). Chicanismo as memory: The fictions of Rudolfo Anaya, Nash Candelaria, Sandra Cisneros, and Ron Arias. In Amritjit Singh, Jose T. Skerrett,Jr. & Robert E. Hogan (Eds.), Memory and Cultural Politics: New Approaches to American Ethnic Literatures (pp. 320–39). Boston: Northeastern UP.

- Lomelí, F. A., & Martínez, J. A. (Eds.) (1985). Anaya, Rudofo Alfonso. In Chicano Literature: A reference guide (pp. 34–51). Westport: Greenwood Press.

- Magill, F. N. (Ed.) (1994). Bless Me, Ultima. In Masterpieces of Latino Literature (1st ed., pp. 38–41). New York: Harper Collins.

- Martinez-Cruz, Paloma. (2004). Interpreting the (Me)xican wise woman: Convivial and representation. Ph.D. dissertation, Columbia University, United States – New York. Retrieved January 10, 2012, from Dissertations & Theses: A&I.(Publication No. AAT 3110162).

- Milligan, B. (1998, August 23). Anaya says absence of coverage will kill Latino culture. San Antonio Express-News, p. 1H.

- Park, C.D. (2002). “Ultima: myth, magic and mysticism in teaching and learning.” In Jose Villarino & Arturo Ramirez (Eds.), Aztlán, Chicano culture and folklore: An anthology, (3rd Edition). pp. 187–198.

- Perez-Torres, R. (1995). Movements in Chicano Poetry: Against myths, against margins. New York: Cambridge University Press. (cf. Four or five worlds: Chicano/a literary criticism as postcolonial discourse)

- Poey, Delia Maria (1996). Border crossers and coyotes: A reception study of Latin American and Latina/o literatures. Ph.D. dissertation, Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College, United States – Louisiana. Retrieved January 8, 2012, from Dissertations & Theses: A&I.(Publication No. AAT 9712859).

- Rudolfo A(lfonso) Anaya. (1983). In S. R. Gunton & J. C. Stine (Eds.), Contemporary literary criticism, 23, 22–27. Detroit: Gale Research.

- Taylor,P. B. (1994 Autumn). The Chicano translation of Troy: Epic Topoi in the novels of Rudolfo A. Anaya. MELUS, 19, 19–35.

- Tonn, H. (1990). Bless Me, Ultima: Fictional response to times of transition. In César A. González-T. (Ed.), Rudolfo A. Anaya: Focus on Criticism (pp. 1–12). La Jolla, CA: Lalo Press.

- Vallegos, T. (1983 Winter). Ritual process and the family in the Chicano novel. MELUS, 10, 5–16.

- Villar Raso, M. & Herrera-Sobek, Maria.( 2001 Fall). A Spanish novelist's perspective on Chicano/a literature. Journal of Modern Literature, 25,17–34.

External links

- Ecstasy Ecstasy (emotion) retrieved April 9, 2012.

- Bless Me Ultima Themes. retrieved April 1, 2012.

- Jack Komperda.(2008, August 1). Latino culture focus of reading program. Daily Herald,5. Retrieved January 8, 2012, from ProQuest Newsstand. (Document ID: 1616340911).

- Garth Stapely.(Oct 13, 2009).Book-Banning Prompts School Board Interest; Election 2009 See sidebar:'Newman-Crows Landing Unified School District Board of Education' attached to end of story.The Modesto Bee. Modesto, CA: p. B.3. retrieved January 8, 2011.

- School Board Bans Book From Sophomore Required Reading List ... retrieved December 28, 2011.

- BLESS ME ULTIMA banned and burned in Colorado retrieved December 28, 2011.

- And What You Sought to Do Will Undo You retrieved December 28, 2011.

- El Centro Su Teatro Home Page

- Vortex Theatre

- Teatro Vision