Black Elk

| Black Elk | |

|---|---|

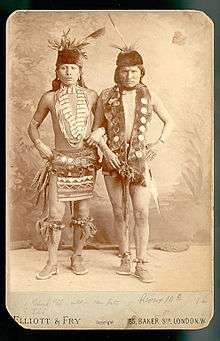

Black Elk (L) and Elk of the Oglala Lakota photographed in London, England in their grass dance regalia while touring with Buffalo Bill's Wild West, 1887 | |

| Born |

December 1, 1863 Little Powder River, Wyoming |

| Died |

August 19, 1950 (aged 86) Pine Ridge, South Dakota |

| Resting place | Saint Agnes Catholic Cemetery, Manderson, South Dakota |

| Spouse |

Katie War Bonnet (1892–1903) Anna Brings White (1905–1941) Ellen (?–1950) |

| Children |

Benjamin (1899–1973) John Lucy Looks Twice (?–1978) |

Heȟáka Sápa (Black Elk) (December 1863 – August 19, 1950)[1] was a famous wičháša wakȟáŋ (medicine man and holy man) and heyoka of the Oglala Lakota (Sioux) who lived in the present-day United States, primarily South Dakota. He was a second cousin of the war chief Crazy Horse.

Near the end of his life, Black Elk met with amateur ethnologist John Neihardt and recounted to him his religious vision, events from his life, and details of Lakota culture. Neihardt edited a translated record and published Black Elk Speaks in 1932. The words of Black Elk have since been published in numerous editions, most recently in 2008. There has been great interest in his work among members of the American Indian Movement since the 1970s and others who have wanted to learn more about a Native American religion.

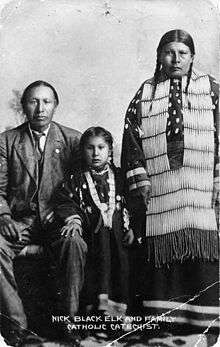

Black Elk's first wife Katie converted to Roman Catholicism, and they had their three children baptized as Catholics. After Katie's death, in 1904 Black Elk, then in his 40s, converted to Catholicism. He also became a catechist, teaching others about Christianity. He married again and had more children with his second wife; they were also baptized and reared as Catholic. He said his children "had to live in this world."[2]

Childhood

Black Elk was born into an Oglala Lakota family in December 1863 along the Little Powder River (at a site thought to be in the present-day state of Wyoming).[3]:3 According to the Lakota way of measuring time (referred to as Winter counts), Black Elk was born "the Winter When the Four Crows Were Killed on Tongue River".[3]:101

Vision

When Black Elk was nine years old, he was suddenly taken ill; he lay prone and unresponsive for several days. During this time he had a great vision in which he was visited by the Thunder Beings (Wakinyan), and taken to the Grandfathers — spiritual representatives of the six sacred directions: west, east, north, south, above, and below. These "... spirits were represented as kind and loving, full of years and wisdom, like revered human grandfathers."[3]:preface When he was seventeen, Black Elk told a medicine man, Black Road, about the vision in detail. Black Road and the other medicine men of the village were "astonished by the greatness of the vision."[3]:6–7

Black Elk had learned many things in his vision to help heal his people. He had come from a long line of medicine men and healers in his family; his father was a medicine man, as were his paternal uncles. Late in his life as an elder, he related to John G. Neihardt the vision that occurred to him. Among other things he saw a great tree that symbolized the life of the earth and all people.[4] Neihardt recorded his account in great detail, later publishing it as Black Elk Speaks. Since the late 20th century, Black Elk's words have received renewed attention, including from non-Lakota. An annotated edition was published by the State University of New York in 2008.

In his vision, Black Elk is taken to the center of the earth, and to the central mountain of the world. Mythologist Joseph Campbell explains this recurring symbol among religions as "the axis mundi, the central point, the pole around which all revolves ... the point where stillness and movement are together ...." Black Elk was residing at the axis of the six sacred directions. Campbell viewed Black Elk's statement as key to understanding myth and symbols.[5]

As Black Elk related:

And while I stood there I saw more than I can tell and understood more than I saw; for I was seeing in a sacred manner the shapes of all things in the spirit, and the shape of all shapes as they must live together like one being. And I saw that the sacred hoop of my people was one of many hoops that made one circle, wide as daylight and as starlight, and in the center grew one mighty flowering tree to shelter all the children of one mother and one father. And I saw that it was holy.[3]:intro., 97

Black Elk had many visions throughout his life, which reinforced what he had seen and felt as a boy. He worked among his people as a healer and medicine man.

Buffalo Bill's Wild West

In 1887, Black Elk traveled to England with Buffalo Bill's Wild West,[6] an experience he described in chapter twenty of Black Elk Speaks.[7] On May 11, 1887, the troop put on a command performance for Queen Victoria, whom they called "Grandmother England." Black Elk was among the crowd at her Golden Jubilee.[8]

In spring 1888, Buffalo Bill's Wild West set sail for the United States. Black Elk became separated from the group and the ship left without him, stranding him with three other Lakota. They subsequently joined another wild west show and he spent the next year touring in Germany, France, and Italy. When Buffalo Bill arrived in Paris in May 1889, Black Elk obtained a ticket to return home to Pine Ridge, arriving in autumn of 1889. During his sojourn in Europe, Black Elk was given an "abundant opportunity to study the white man's way of life," and he learned to speak rudimentary English.[3]:9

Wounded Knee

Black Elk participated in the fighting at Wounded Knee in 1890. While on horseback, he charged soldiers and helped to rescue some of the wounded. He arrived after many of Spotted Elk's (Big Foot's) band of people had been shot, and he was grazed by a bullet to his hip.[9]

Later years

For at least a decade, beginning in 1934, Black Elk returned to work related to his performances earlier in life with Buffalo Bill. He organized an Indian show to be held in the sacred Black Hills. But, unlike the Wild West shows, used to glorify Indian warfare, Black Elk created a show to teach tourists about Lakota culture and traditional sacred rituals, including the Sun Dance.[10]

Family

Black Elk married his first wife, Katie War Bonnet, in 1892. She converted to Catholicism, and all three of their children were baptized as Catholics.

After Katie's death in 1903, Black Elk became a Catholic the next year in 1904, when he was in his 40s. He was christened with the name of Nicholas and later served as a catechist in the church.[3]:14 [11]:44 After this, other medicine men, including his nephew Fools Crow, referred to him both as Black Elk and Nicholas Black Elk.[11]:44

The widower Black Elk married again in 1905 to Anna Brings White, a widow with two daughters. Together they had three more children, whom they also had baptized as Catholic. As he later said, his children had to live in "this world." (See below, account by Hilda Neihardt.)[2] The couple were together until her death in 1941.

Black Elk was a leader in the revival of the Sun Dance (an important religious ceremony among several tribes) and its reinstatement in Lakota life. Lakota traditionalists now follow his version of the dance.[12]

In the early 1930s, Black Elk revealed the story of his life, and a number of sacred Sioux rituals to John Neihardt and Joseph Epes Brown for publication. Black Elk worked with Neihardt to give a first-hand account of his experiences and that of the Lakota people. His son Ben translated Black Elk's stories into English as he spoke. Neihardt's daughter Enid recorded these accounts. She later arranged them in chronological order for Neihardt's use. Thus the process had many steps and more people than Black Elk and Neihardt were involved in the recounting and recording.[12]

After Black Elk told Neihardt his vision over the course of several days, Neihardt asked why Black Elk had "put aside" his old religion. According to [Neihardt's daughter] Hilda, Black Elk replied, "My children had to live in this world."[2] Hilda Neihardt relates that just before his death, Black Elk took his pipe and told his daughter Lucy Looks Twice, "The only thing I really believe is the pipe religion."[13]

Record

Since the 1970s, the book Black Elk Speaks has become an important source for studying Native spirituality. With the rise of Native American activism, there was increasing interest among many in their traditional religions. Within the American Indian Movement, for instance, Black Elk Speaks was an important source for those seeking religious and spiritual inspiration. They also sought out Black Elk's nephew Frank Fools Crow, also a medicine man, for information on Native traditions.[12] In the same period, there has been rising interest among non-Native Americans in Native culture and religions.

On August 11, 2016, the US Board on Geographic Names officially renamed Harney Peak, the highest point in South Dakota, Black Elk Peak in honor of Nicholas Black Elk and in recognition of the significance of the mountain to Native Americans.

- Books of Black Elk's accounts

- Black Elk Speaks: Being the Life Story of a Holy Man of the Oglala Sioux (as told to John G. Neihardt), Bison Books, 2004 (originally published in 1932) : Black Elk Speaks

- The Sixth Grandfather: Black Elk's Teachings Given to John G. Neihardt, edited by Raymond J. DeMallie, University of Nebraska Press; new edition, 1985. ISBN 0-8032-1664-5.

- The Sacred Pipe: Black Elk's Account of the Seven Rites of the Oglala Sioux (as told to Joseph Epes Brown), MJF Books, 1997

- Spiritual Legacy of the American Indian (as told to Joseph Epes Brown), World Wisdom, 2007

- Books about Black Elk

- Black Elk: Holy Man of the Oglala, by Michael F. Steltenkamp, University of Oklahoma Press; 1993. ISBN 0-8061-2541-1

- Nicholas Black Elk: Medicine Man, Missionary, Mystic, by Michael F. Steltenkamp, University of Oklahoma Press; 2009. ISBN 0-8061-4063-1

- The Sixth Grandfather: Black Elk's Teachings Given to John G. Neihardt, edited by Raymond J. DeMallie; 1985

- Black Elk and Flaming Rainbow: Personal Memories of the Lakota Holy Man, by Hilda Neihardt, University of Nebraska Press, 2006. ISBN 0-8032-8376-8

- Black Elk’s Religion: The Sun Dance and Lakota Catholicism, by Clyde Holler, Syracuse University Press; 1995

- Black Elk: Colonialism and Lakota Catholicism, by Damian Costello, Orbis Books; 2005.

- Black Elk Reader, edited by Clyde Holler, Syracuse University Press; 2000

See also

- Black Elk Wilderness

- I Remain Alive: the Sioux Literary Renaissance

- John Fire Lame Deer

- Sitting Bull

Notes

- ↑ Sources differ

- 1 2 3 DeMallie, Raymond J., ed. (1985). The Sixth Grandfather: Black Elk's Teachings Given to John G. Neihardt. University of Nebraska Press. p. 47. ISBN 0-8032-6564-6.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 DeMallie, Raymond J (1984). The Sixth Grandfather: Black Elk's teachings given to John G. Neihardt. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0-8032-1664-5.

- ↑ Neihardt, John, ed., Black Elk Speaks, annotated edition, published by SUNY, 2008, p. 33.

- ↑ Campbell, Joseph (1991). The Power of Myth (with Bill Moyers). Anchor Books edition (non-illustrated smaller-format edition). p. 111. ISBN 0 385 41886 8.

- ↑ "Tracking the Salford Sioux"

- ↑ Black Elk Speaks

- ↑ "When she came to where we were, her wagon stopped and she stood up. Then all those people stood up and roared and bowed to her: "but she bowed to us." Neihardt, John, ed., Black Elk Speaks, annotated edition, published by SUNY, 2008, pp. 176-177.

- ↑ John Gneisenau Neihardt (1985). The Sixth Grandfather: Black Elk's Teachings Given to John G. Neihardt. U of Nebraska Press. pp. 274–. ISBN 0-8032-6564-6.

- ↑ John G. Neihardt (1 August 2008). Black Elk Speaks: Being the Life Story of a Holy Man of the Oglala Sioux. SUNY Press. p. 313. ISBN 978-1-4384-2538-2. Retrieved 24 February 2013.

- 1 2 Mails, Thomas E. (1979). Fools Crow. Garden City, NJ: Doubleday. ISBN 0385113323.

- 1 2 3 Clyde Holler (2000). The Black Elk Reader. Syracuse University Press. pp. 39–43. ISBN 978-0-8156-2836-1. Retrieved 24 February 2013.

- ↑ Neihardt, Hilda (1999). Black Elk & Flaming Rainbow: Personal Memories of the Lakota Holy Man and John Neihardt. University of Nebraska Press. p. 119. ISBN 0-8032-3338-8.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Black Elk |

- Black Elk at Find a Grave

- "Writings of Black Elk" from C-SPAN's American Writers: A Journey Through History