Black Egyptian hypothesis

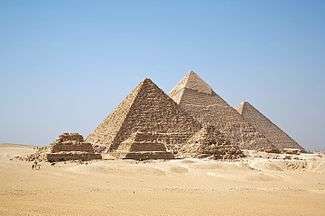

The Black Egyptian hypothesis is the contested hypothesis that Ancient Egypt was a Black civilization. It includes a particular focus on identifying links to Sub Saharan cultures and the questioning of the race of specific notable individuals from Dynastic times, including Tutankhamun,[1] the king represented in the Great Sphinx of Giza,[2][3] and Cleopatra.[4][5][6]

Since the second half of the 20th century, typological and hierarchical models of race have increasingly been rejected by scientists, and most (but not all) scholars have held that applying modern notions of race to ancient Egypt is anachronistic.[7][8][9]

At the UNESCO "Symposium on the Peopling of Ancient Egypt and the Deciphering of the Meroitic Script" in Cairo in 1974, the Black hypothesis met with profound disagreement.[10] Nearly all participants concluded that the Ancient Egyptian population was indigenous to the Nile Valley, and was made up of people from north and south of the Sahara who were differentiated by their color.[11]

History

Some modern scholars such as W. E. B. Du Bois,[12] Chancellor Williams,[13] Cheikh Anta Diop,[14][15][16] John G. Jackson,[17] Ivan van Sertima,[18] Martin Bernal[19] and Segun Magbagbeola[20] have supported the theory that the Ancient Egyptian society was mostly Black.[21] The frequently criticized Journal of African Civilizations[22] has continually advocated that Egypt should be viewed as a Black civilization.[23][24] The debate was popularized throughout the 20th century by the aforementioned scholars, with many of them using the terms "Black," "African," and "Egyptian" interchangeably,[25] despite what Frank Snowden calls "copious ancient evidence to the contrary."[26][27] In the mid 20th century, the proponents of the Black African theory presented what G. Mokhtar referred to as "extensive" and "painstakingly researched" evidence[14][15][16][28][29] to support their views, which contrasted sharply with prevailing views on Ancient Egyptian society. Diop and others believed the prevailing views were fueled by scientific racism and based on poor scholarship.[30] Diop used a multi-faceted approach to counteract prevailing views on the Ancient Egyptian's origins and ethnicity.

Position of modern scholarship

Since the second half of the 20th century, most (but not all) scholars have held that applying modern notions of race to ancient Egypt is anachronistic.[7][8][9] The focus of some experts who study population biology has been to consider whether or not the Ancient Egyptians were primarily biologically North African rather than to which race they belonged.[31]

In 1975, the mummy of Ramesses II was taken to France for preservation. The mummy was also forensically tested by Professor Pierre-Fernand Ceccaldi, the chief forensic scientist at the Criminal Identification Laboratory of Paris. Professor Ceccaldi determined that: "Hair, astonishingly preserved, showed some complementary data - especially about pigmentation: Ramses II was a ginger haired 'cymnotriche leucoderma'." The description given here refers to a fair-skinned person with wavy ginger hair.[32][33]

In 2008, S. O. Y. Keita wrote that "There is no scientific reason to believe that the primary ancestors of the Egyptian population emerged and evolved outside of northeast Africa.... The basic overall genetic profile of the modern population is consistent with the diversity of ancient populations that would have been indigenous to northeastern Africa and subject to the range of evolutionary influences over time, although researchers vary in the details of their explanations of those influences."[34]

Stuart Tyson Smith writes in the 2001 Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt that "Any characterization of race of the ancient Egyptians depends on modern cultural definitions, not on scientific study. Thus, by modern American standards it is reasonable to characterize the Egyptians as "black", while acknowledging the scientific evidence for the physical diversity of Africans."[35]

Greek historians

The Black African model relied heavily on the interpretation of the writings of Classical historians, who were writing during and after the time when Egypt was a province of the Persian Empire, i.e. long after the golden age of pharaohic Egypt had passed and when Egypt was full of foreigners. Several Ancient Greek historians noted that Egyptians had complexions that were "melanchroes".[37] There is considerable controversy over the translation of melanchroes. Most scholars translate it as black.[38][39][40][41][42][43][44] Alan B Lloyd wrote that "there is no linguistic justification for relating this description to negroes. Melanchroes could denote any colour from bronzed to black and negroes are not the only physical type to show curly hair. These characteristics would certainly be found in many Egs [Egyptians], ancient and modern, but they are at variance with what we should expect amongst the inhabitants of the Caucasus area.[45] Some of the most often quoted historians are Strabo, Diodorus Siculus, and Herodotus.[38] Herodotus states in a few passages that the Egyptians were black/dark. According to most translations, Herodotus states that a Greek oracle was known to be from Egypt because she was "black", that the natives of the Nile region are "black with heat", and that Egyptians were "black skinned with woolly hair".[39] Lucian observes an Egyptian boy and notices that he is not merely black, but has thick lips.[38] Diodorus Siculus mentioned that the Aethiopians considered the Egyptians a colony.[46] Appollodorus, a Greek, calls Egypt the country of the black footed ones.[38] Aeschylus, a Greek poet, wrote that Egyptian seamen had "black limbs."[47] Greeks sometimes referred to Egyptians as Aethiopians[48] – not to be confused with inhabitants of the modern-day nation of Ethiopia who were instead referred to as Abyssinians or Habesha and their land as Abyssinia.

Gaston Maspero states that "by the almost unanimous testimony of ancient [Greek] historians, they [Ancient Egyptians] belonged to the African race, which settled in Ethiopia."[49][50] Simson Najovits states that Herodotus "made clear ethnic and national distinctions between Aigyptios (Egyptians) and the peoples whom the Greeks referred to as Aithiops (Ethiopians)."[51]

Many scholars (Aubin, Heeren, Davidson, Diop, Poe, Welsby, Celenko, Volney, Montet, Bernal, Jackson, DuBois, Strabo), ancient and modern, routinely cite Herodotus in their works on the Nile Valley. Some of these scholars (Welsby, Heeren, Aubin, Diop, etc.) explicitly mention the reliability of Herodotus' work on the Nile Valley and demonstrate corroboration of Herodotus' writings by modern scholars. Welsby said that "archaeology graphically confirms some of Herodotus' observations."[52] A.H.L. Heeren (1838) quoted Herodotus throughout his work and provided corroboration by scholars of his day regarding several passages (source of the Nile, location of Meroe, etc.).[53] To further his work on the Egyptians and Assyrians, Aubin uses Herodotus' accounts in various passages and defends Herodotus' position against modern scholars. Aubin said Herodotus was "the author of the first important narrative history of the world" and that Herodotus "visited Egypt."[54] Diop provides several examples (e.g. the inundations of the Nile) that he claims support his view that Herodotus was "quite scrupulous, objective, scientific for his time." Diop also claims that:

- Herodotus "always distinguishes carefully between what he has seen and what he has been told";

- "One must grant that he was at least capable of recognizing the skin color of inhabitants."[55]

- "For all the writers who preceded the ludicrous and vicious falsifications of modern Egyptology, and the contemporaries of the ancient Egyptians (Herodotus, Aristotle, Diodorus, Strabo, and others), the Black identity of the Egyptian was an evident fact."

Snowden claims that Diop "not only distorts his classical sources but also omits reference to Greek and Latin authors who specifically call attention to the physical differences between Egyptians and Ethiopians."[56] Diop also claims that Strabo corroborated Herodotus' ideas about the Black Egyptians, Aethiopians, and Colchians.[15][49] About the claim of Herodotus that the Pharaoh Sesostris campaigned in Europe, and that he left a colony in Colchia, Fehling states that "there is not the slightest bit of history behind the whole story".[57]

Many scholars regard the works of Herodotus as being unreliable as historical sources. Fehling writes of "a problem recognized by everybody", namely that much of what Herodotus tells us cannot be taken at face value.[57] Sparks writes that "In antiquity, Herodotus had acquired the reputation of being unreliable, biased, parsimonious in his praise of heroes, and mendacious".[58][59][60][61][62] Najovits writes that “Herodotus fantasies and inaccuracies are legendary.”[63] Voltaire and Hartog both described Herodotus as the "father of lies".[64][65]

The reliability of Herodotus is particularly criticized when writing about Egypt. Alan B. Lloyd states that as a historical document, the writings of Herodotus are seriously defective, and that he was working from "inadequate sources".[66] Nielsen writes that: "Though we cannot entirely rule out the possibility of Herodotus having been in Egypt, it must be said that his narrative bears little witness to it."[67] Fehling states that Herodotus never traveled up the Nile River, and that almost everything he says about Egypt and Aethiopia is doubtful.[57][68]

Supporters of the Black theory saw the Aethiopians and Egyptians as racially and culturally similar,[46][69] while others felt that the Ancient Egyptians and Aethiopians were two ethnically distinct groups.[70] This is one of the most popular and controversial arguments for this theory.[71][72] Snowden mentions that Greeks and Romans knew of "negroes of a red, copper-colored complexion...among African tribes",[73] and proponents of the Black theory believed that the Black racial grouping was comprehensive enough to absorb the red and black skinned images in Ancient Egyptian iconography.[73] The British Africanist Basil Davidson stated "Whether the Ancient Egyptians were as black or as brown in skin color as other Africans may remain an issue of emotive dispute; probably, they were both. Their own artistic conventions painted them as pink, but pictures on their tombs show they often married queens shown as entirely black, being from the south : while the Greek writers reported that they were much like all the other Africans whom the Greeks knew."[74]

Melanin samples

While at the University of Dakar, Diop used microscopic laboratory analysis to measure the melanin content of skin samples from several Egyptian mummies (from the Mariette excavations). The melanin levels found in the dermis and epidermis of that small sample led Diop to classify all the Ancient Egyptians as "unquestionably among the Black races."[75] At the UNESCO conference, Diop invited other scholars to examine the skin samples.[76][77] Diop also asserted that Egyptians shared the "B" blood type with black Africans.

The other scholars at the symposium however rejected Diop’s Black-Egyptian theory.[78]

Language

Diop and Obenga attempted to linguistically link Egypt and Africa, by arguing that the Ancient Egyptian language was related to Diop's native Wolof (Senegal).[79] Diop's work was well received by the political establishment in the post-colonial formative phase of the state of Senegal, and by the Pan-Africanist Négritude movement, but was rejected by mainstream scholarship. In drafting that section of the report of the UNESCO Symposium, Diop claimed that Diop and Obenga's linguistic reports had a large measure of agreement and were regarded as "very constructive."[80] However, in the discussion thereof in the work Ancient Civilizations of Africa, Volume 2, the editor has inserted a footnote stating that these are merely Diop’s opinions and that they were not accepted by all the experts participating.[81] In particular, Prof Abdelgadir M. Abdalla stated that “The linguistic examples given by Prof Diop were neither convincing nor conclusive.”[82]

Cultural practices

According to Diop, historians are in general agreement that the Aethiopians, Egyptians, Colchians, and people of the Southern Levant were among the only people on Earth practicing circumcision, which confirms their cultural affiliations, if not their ethnic affiliation.[83] The Egyptian (adolescent) style of circumcision was different from how circumcision is practiced in other parts of the world, but similar to how it is practiced throughout the African continent.[84] "Ancient writings discuss (Egyptian) circumcision in religious terms"[85] and a 6th Dynasty tomb shows circumcision being performed by a "circumcising priest, rather than a physician." [86] "The practice of circumcising by religious, rather than medical, authorities is still common throughout Africa today."[84] Furthermore, in both Ancient Egypt and modern Africa, young boys were circumcised in large groups.[87]

Circumcision was practiced in Egypt at a very early date. Strouhal mentions that "the earliest archaeological evidence for circumcision was found in the southern Nile Valley and dates from the Neolithic period, some 6000 years ago." The remains of circumcised individuals are cited as proof.[85] Similarly, Doyle states "It is now thought that the Egyptians adopted circumcision much earlier" (than the confirmed 2400 BC date), "from peoples living further south in today’s Sudan and Ethiopia, where dark-skinned peoples are known to have practised circumcision." Evidence suggests that circumcision was practiced in the Arabian peninsula "from where, in the fourth millennium BCE, two groups of people migrated into what we today call Iraq. These were the Sumerians and, slightly later, the Semites, the forefathers of the Hebrews."[88]

Biblical Ham, blackness, and Ham's offspring

According to Diop, Bernal, and other scholars, "Ham was the ancestor of Negroes and Egyptians." According to Bernal, "the Talmudic interpretation that the curse of Ham (the father of Canaan and Mizraim, Egypt) was blackness was widespread in the 17th century."[41] Ham was the father of Mizraim (the Hebrew word for Egypt), Phut, Kush, and Canaan. For Diop, Ham means "heat, black, burned" in Hebrew, an etymology which became popular in the 18th century.[89] Kush is positively identified with black Africa. Furthermore, "If the Egyptians were Negroes, sons of Ham...it is not by chance that this curse on the father of Mesraim, Phut, Kush, and Canaan, fell only on Canaan."[90] A review of David Goldenberg's The Curse of Ham: Race and Slavery in Early Judaism, Christianity and Islam states that Goldenberg "argues persuasively that the biblical name Ham bears no relationship at all to the notion of blackness and as of now is of unknown etymology."[91]

Kemet

| km biliteral | kmt (place) | kmt (people) | |||||||||

|

|

|

Supporters of the Black Egyptian hypothesis claim that the name Kemet, used by Egyptians to describe themselves or their land (depending on your point of view), meant "Black".[92]

Ancient Egyptians referred to their homeland as Kmt (conventionally pronounced as Kemet). According to Diop, the Egyptians referred to themselves as "Black" people or kmt, and km was the etymological root of other words, such as Kam or Ham, which refer to Black people in Hebrew tradition.[93][94] Diop,[95] William Leo Hansberry,[95] and Aboubacry Moussa Lam[96] have argued that kmt was derived from the skin color of the Nile valley people, which Diop et al. claim was black.[71][97] The claim that the Ancient Egyptians had black skin has become a cornerstone of Afrocentric historiography,[95] but it is rejected by most Egyptologists.[98]

Mainstream scholars hold that kmt means "the black land" or "the black place", and that this is a reference to the fertile black soil which was washed down from Central Africa by the annual Nile inundation. By contrast the barren desert outside the narrow confines of the Nile watercourse was called dšrt (conventionally pronounced deshret) or "the red land".[95][99] Raymond Faulkner's Concise Dictionary of Middle Egyptian translates kmt into "Egyptians",[100] Gardiner translates it as "the Black Land, Egypt".[101]

At the UNESCO Symposium in 1974, Professors Sauneron, Obenga, and Diop concluded that KMT and KM meant black.[102] However, Professor Sauneron clarified that the Egyptians never used the adjective Kmtyw to refer to the various black peoples they knew of, they only used it to refer to themselves.[82]

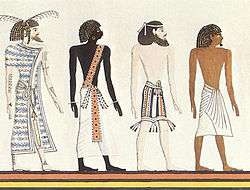

Ancient art

Diop saw the representation of black people in Egyptian art and iconography throughout Egyptian history. University of Chicago scholars state that the skin pigment used in Egyptian paintings to refer to Nubians can range "from dark red to brown to black."[103] This can be observed in paintings from the tomb of the Egyptian Huy, as well as Ramses II's temple at Beit el-Wali.[104] Also, Snowden indicates that Statius spoke of "red Ethiopians" and Romans had accurate knowledge of "negroes of a red, copper-colored complexion...among African tribes."[73]

Professors Vercoutter, Ghallab and Leclant stated that “Egyptian iconography, from the 18th Dynasty onward, showed characteristic representations of black people who had not previously been depicted; these representations meant, therefore, that at least from that dynasty onward the Egyptians had been in contact with peoples who were considered ethnically distinct from them.”[105]

Depictions of Egyptians in art and artifacts are rendered in sometimes symbolic, rather than realistic, pigments. As a result, ancient Egyptian artifacts provide sometimes conflicting and inconclusive evidence of the ethnicity of the people who lived in Egypt during dynastic times.[106][107] Najovits states that "Egyptian art depicted Egyptians on the one hand and Nubians and other blacks on the other hand with distinctly different ethnic characteristics and depicted this abundantly and often aggressively. The Egyptians accurately, arrogantly and aggressively made national and ethnic distinctions from a very early date in their art and literature."[108] He continues that "There is an extraordinary abundance of Egyptian works of art which clearly depicted sharply contrasted reddish-brown Egyptians and black Nubians."[108]

Sculpture and the Sphinx

This debate is best characterized by the controversy over the Great Sphinx of Giza.[109] Scholars supportive of the Black Egyptian hypothesis reviewed Egyptian sculpture from throughout the dynastic period and concluded that the sculptures were consistent with the phenotype of the black race.

Numerous scholars, such as DuBois,[2][110][111] Diop, Asante,[112] and Volney,[113] have characterized the face of the Sphinx as Black, or "Negroid." Around 1785 Volney stated, "When I visited the sphinx...on seeing that head, typically Negro in all its features, I remembered...Herodotus says: "...the Egyptians...are black with woolly hair"..."[114] Another early description of a "Negroid" Sphinx is recorded in the travel notes of a French scholar, who visited in Egypt between 1783 and 1785, Constantin-François Chassebœuf[115] along with French novelist Gustave Flaubert.[116] The identity of the model for the Great Sphinx of Giza is unknown.[117] Virtually all Egyptologists and scholars currently believe that the face of the Sphinx represents the likeness of the Pharaoh Khafra, although a few Egyptologists and interested amateurs have proposed several different hypotheses.

Qustul artifacts

Scholars from the University of Chicago Oriental Institute excavated at Qustul (near Abu Simbel – Modern Sudan), in 1960–64, and found artifacts which incorporated images associated with Egyptian pharaohs. From this Williams concluded that "Egypt and A-group Nubia shared the same official culture", "participated in the most complex dynastic developments", and "Nubia and Egypt were both part of the great East African substratum."[118] Williams also wrote that Qustul in Nubia "could well have been the seat of Egypt's founding dynasty."[119][120] Diop used this as further evidence in support of his Black Egyptian hypothesis.[121] David O'Connor wrote that the Qustul incense burner provides evidence that the A-group Nubian culture in Qustul marked the "pivotal change" from predynastic to dynastic "Egyptian monumental art".[122]

However, "most scholars do not agree with this hypothesis",[123] as more recent finds in Egypt indicate that this iconography originated in Egypt not Nubia, and that the Qustul rulers adopted/emulated the symbols of Egyptian pharaohs.[124][125][126][127][128]

More recent and broader studies have determined that the distinct pottery styles, differing burial practices, different grave goods and the distribution of sites all indicate that the Naqada people and the Nubian A-Group people were from different cultures. Kathryn Bard further states that "Naqada cultural burials contain very few Nubian craft goods, which suggests that while Egyptian goods were exported to Nubia and were buried in A-Group graves, A-Group goods were of little interest further north."[129]

See also

Notes

- ↑ "Tutankhamun was not black: Egypt antiquities chief". AFP. Google News. Sep 25, 2007. Archived from the original on February 13, 2012. Retrieved May 28, 2012.

- 1 2 Graham W. Irwin (1977-01-01). Africans abroad: a documentary history of the Black Diaspora in Asia, Latin ... Books.google.co.uk. Retrieved 2016-05-28.

- ↑ Robert Schoch ,"Great Sphinx Controversy". robertschoch.net. 1995. Archived from the original on February 4, 2012. Retrieved May 29, 2012., A modified version of this manuscript was published in the "Fortean Times" (P.O. Box 2409, London NW5 4NP) No. 79, February March, 1995, pp. 34 39.

- ↑ Hugh B. Price ,"Was Cleopatra Black?". The Baltimore Sun. September 26, 1991. Retrieved May 28, 2012.

- ↑ Charles Whitaker ,"Was Cleopatra Black?". Ebony. Feb 2002. Retrieved May 28, 2012. In support of this, he cites a few examples, one of which is a chapter entitled "Black Warrior Queens," published in 1984 in Black Women in Antiquity, part of The Journal of African Civilization series. It draws heavily on the work of J.A. Rogers.

- ↑ Mona Charen ,"Afrocentric View Distorts History and Achievement by Blacks". St. Louis Post-Dispatch. February 14, 1994. Retrieved May 29, 2012.

- 1 2 Black Athena Revisited. Books.google.co.za. p. 162. Retrieved 2016-05-28.

- 1 2 Encyclopedia of the Archaeology of Ancient Egypt. Books.google.co.za. p. 329. Retrieved 2016-05-28.

- 1 2 Stephen Howe. Afrocentrism: Mythical Pasts and Imagined Homes. Books.google.co.za. p. 19. Retrieved 2016-05-28.

- ↑ Muḥammad Jamāl al-Dīn Mukhtār. "Ancient Civilizations of Africa". Books.google.co.za. p. 43. Retrieved 2016-05-28.

- ↑ Muḥammad Jamāl al-Dīn Mukhtār. Ancient Civilizations of Africa. Books.google.co.za. p. 10. Retrieved 2016-05-28.

- ↑ DuBois, W.E.B. (2003). The World and Africa. New York: International Publishers. pp. 81–147. ISBN 0-7178-0221-3.

- ↑ Williams, Chancellor (1987). The Destruction of Black Civilization. Chicago, Illinois: Third World Press. pp. 59–135. ISBN 0-88378-030-5.

- 1 2 Diop, Cheikh Anta (1974). The African Origin of Civilization. Chicago, Illinois: Lawrence Hill Books. pp. 1–9, 134–155. ISBN 1-55652-072-7.

- 1 2 3 Diop, Cheikh Anta (1981). Civilization or Barbarism. Chicago, Illinois: Lawrence Hill Books. pp. 103–108. ISBN 1-55652-048-4.

- 1 2 Mokhtar, G. (1990). General History of Africa. California, USA: University of California Press. pp. 1–118. ISBN 0-520-06697-9.

- ↑ Jackson, John G. (1970). Introduction to African Civilizations. New York, NY, USA: Citadel Press. pp. 60–156. ISBN 0-8065-2189-9.

- ↑ Sertima, Ivan Van (1985). African Presence in Early Asia. New Brunswick, USA: Transaction Publishers. pp. 59–65, 177–185. ISBN 0-88738-637-7.

- ↑ Bernal, Martin (1987). Black Athena. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press. pp. 63–75, 98–101, 439–443. ISBN 0-8135-1277-8.

- ↑ Magbagbeola, Segun (2012). Black Egyptians: The African Origins of Ancient Egypt. United Kingdom: Akasha Publishing Ltd. pp. 12–14. ISBN 978-09573695-0-4.

- ↑ Mokhtar, G. (1990). General History of Africa. California, USA: University of California Press. pp. 31–32, 46, 52. ISBN 0-520-06697-9.

- ↑ Muhly: "Black Athena versus Traditional Scholarship," Journal of Mediterranean Archaeology 3, no 1: 83–110

- ↑ Snowden p. 117

- ↑ "Four Unforgettable Scholars, Countless Gifts to the World". Journalofafricancivilizations.com. Retrieved 2016-05-28.

- ↑ Snowden p.116 of Black Athena Revisited"

- ↑ Snowden, Jr., Frank M. (Winter 1997). "Misconceptions about African Blacks in the Ancient Mediterranean World: Specialists and Afrocentrists". Arion: A Journal of Humanities and the Classics. Trustees of Boston University. 4 (3): 43. JSTOR 20163634.

- ↑ Frank M. Snowden Jr. (1997). "Misconceptions about African Blacks in the Ancient Mediterranean World: Specialists and Afrocentrists" (PDF). Arion. Trustees of Boston University. pp. 28–50.

- ↑ Mokhtar, G. (1990). General History of Africa. California, USA: University of California Press. p. 37. ISBN 0-520-06697-9.

- ↑ Mokhtar, G. (1990). General History of Africa. California, USA: University of California Press. p. 55. ISBN 0-520-06697-9.

- ↑ Diop, Cheikh Anta (1974). The African Origin of Civilization. Chicago, Illinois: Lawrence Hill Books. pp. 1–9, 24–84. ISBN 1-55652-072-7.

- ↑ S.O.Y. Keita, S. O. Y. (1995). "Studies and Comments on Ancient Egyptian Biological Relationships". International Journal of Anthropology. 10 (2–3): 107–123. doi:10.1007/BF02444602.

- ↑ Ceccaldi, Pierre (1987). "Research on the Mummy of Ramasses II". Bulletin de l'Academie de médecine. 171:1 (1): 119.

- ↑ "Bulletin de l'Académie nationale de médecine". Gallica.

- ↑ Keita, S.O.Y. (Sep 16, 2008). "Ancient Egyptian Origins:Biology". National Geographic. Retrieved 15 June 2012.

- ↑ Stuart Tyson Smith (2001) The Oxford encyclopedia of ancient Egypt, Volume 3. Edited by Redford; Oxford University Press. p. 27-28

- ↑ Hodel-Hoenes, S & Warburton, D (trans), Life and Death in Ancient Egypt: Scenes from Private Tombs in New Kingdom Thebes, Cornell University Press, 2000, p.268.

- ↑ Herodotus, Histories 2.104.2.

- 1 2 3 4 Mokhtar, G. (1990). General History of Africa. California, USA: University of California Press. pp. 15–60. ISBN 0-520-06697-9.

- 1 2 Herodotus (2003). The Histories. London, England: Penguin Books. pp. 103, 119, 134–135, 640. ISBN 978-0-14-044908-2.

- ↑ Snowden, Frank (1970). Blacks in Antiquity. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. pp. 101, 104–106, 109.

- 1 2 Bernal, Martin (1987). Black Athena. New Brunswick, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press. p. 242. ISBN 978-0-8135-1276-1.

- ↑ Shavit, Yaacov. History in Black: African-Americans in Search of an Ancient Past. London: Frank Cass Publishers. p. 154. ISBN 0-7146-5062-5.

- ↑ Byron, Gay (2002). Symbolic Blackness and Ethnic Difference in Early Christian Literature. London and New York: Routledge. p. 4. ISBN 0-415-24369-6.

- ↑ Alan B. Lloyd. Herodotus. Books.google.co.za. p. 22. Retrieved 2016-05-28.

- ↑ Alan B. Lloyd. Herodotus. Books.google.co.za. Retrieved 2016-05-28.

- 1 2 Snowden, Frank (1970). Blacks in Antiquity. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. p. 109.

- ↑ Mokhtar, G. (1990). General History of Africa. California, USA: University of California Press. p. 26. ISBN 0-520-06697-9.

- ↑ Αἰθίοψ in Liddell, Scott, A Greek–English Lexicon: "Αἰθίοψ , οπος, ὁ, fem. Αἰθιοπίς , ίδος, ἡ (Αἰθίοψ as fem., A.Fr.328, 329): pl. 'Αἰθιοπῆες' Il.1.423, whence nom. 'Αἰθιοπεύς' Call.Del.208: (αἴθω, ὄψ):— properly, Burnt-face, i.e. Ethiopian, negro, Hom., etc.; prov., Αἰθίοπα σμήχειν 'to wash a blackamoor white', Luc.Ind. 28." Cf. Etymologicum Genuinum s.v. Αἰθίοψ, Etymologicum Gudianum s.v.v. Αἰθίοψ. "Αἰθίοψ". Etymologicum Magnum (in Greek). Leipzig. 1818.

- 1 2 Diop, Cheikh Anta (1974). The African Origin of Civilization. Chicago, Illinois: Lawrence Hill Books. p. 2. ISBN 1-55652-072-7.

- ↑ Mary R. Lefkowitz, Guy MacLean Rogers: Black Athena Revisited, The University of North Carolina Press 1996, ISBN 0-8078-4555-8, pg. 118

- ↑ Egypt, the Trunk of the Tree: A Modern Survey of an Ancient Land, by Simson Najovits, pg 319

- ↑ Welsby, Derek (1996). The Kingdom of Kush. London: British Museum Press. p. 40. ISBN 0-7141-0986-X.

- ↑ Heeren, A.H.L. (1838). Historical researches into the politics, intercourse, and trade of the Carthaginians, Ethiopians, and Egyptians. Michigan: University of Michigan Library. pp. 13, 379, 422–424. ASIN B003B3P1Y8.

- ↑ Aubin, Henry (2002). The Rescue of Jerusalem. New York, NY: Soho Press. pp. 94–96,100–102,118–121,141–144,328, 336. ISBN 1-56947-275-0.

- ↑ Diop, Cheikh Anta (1974). The African Origin of Civilization. Chicago, Illinois: Lawrence Hill Books. pp. 3–5. ISBN 1-55652-072-7.

- ↑ Black Athena Revisited. Books.google.co.za. p. 118. Retrieved 2016-05-28.

- 1 2 3 Travel Fact and Travel Fiction: Studies on Fiction, Literary Tradition ... Books.google.co.za. p. 1. Retrieved 2016-05-28.

- ↑ Kenton L. Sparks. Ethnicity and Identity in Ancient Israel: Prolegomena to the Study of Ethnic ... Books.google.co.za. p. 59. Retrieved 2016-05-28.

- ↑ David Asheri; Alan Lloyd; Aldo Corcella. A Commentary on Herodotus. Books.google.co.za. p. 74. Retrieved 2016-05-28.

- ↑ Jennifer T. Roberts (2011-06-23). Herodotus: A Very Short Introduction. Books.google.co.za. p. 115. Retrieved 2016-05-28.

- ↑ Alan Cameron. Greek Mythography in the Roman World. Books.google.co.za. p. 156. Retrieved 2016-05-28.

- ↑ John Marincola (2001-12-13). Greek Historians. Books.google.co.za. p. 34. Retrieved 2016-05-28.

- ↑ Simson Najovits. Egypt, the Trunk of the Tree, Vol.II: A Modern Survey of and Ancient Land. Books.google.co.za. p. 320. Retrieved 2016-05-28.

- ↑ Multicultural Writers from Antiquity to 1945: A Bio-bibliographical Sourcebook. Books.google.co.za. p. 171. Retrieved 2016-05-28.

- ↑ David G. Farley (2010-11-30). Modernist Travel Writing: Intellectuals Abroad. Books.google.co.za. p. 21. Retrieved 2016-05-28.

- ↑ Alan B. Lloyd. Herodotus. Books.google.co.za. Retrieved 2016-05-28.

- ↑ Flemming A. J. Nielsen. The Tragedy in History: Herodotus and the Deuteronomistic History. Books.google.co.za. p. 41. Retrieved 2016-05-28.

- ↑ Herodotus: Oxford Bibliographies Online Research Guide - Oxford University Press. Books.google.co.za. p. 21. Retrieved 2016-05-28.

- ↑ Snowden, Frank (1970). Blacks in Antiquity. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. p. 119.

- ↑ Black Athena Revisited. Books.google.co.za. p. 389. Retrieved 2016-05-28.

- 1 2 Mokhtar, G. (1990). General History of Africa. California, USA: University of California Press. pp. 21, 26. ISBN 0-520-06697-9.

- ↑ Herodotus (2003). The Histories. London, England: Penguin Books. pp. 134–135. ISBN 978-0-14-044908-2.

- 1 2 3 Snowden, Frank (1970). Blacks in Antiquity. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. p. 3.

- ↑ Davidson, Basil (1991). African Civilization Revisited: From Antiquity to Modern Times. Africa World Press.

- ↑ Diop, Cheikh Anta (1974). The African Origin of Civilization. Chicago, Illinois: Lawrence Hill Books. pp. 236–243. ISBN 1-55652-072-7.

- ↑ Mokhtar, G. (1990). General History of Africa. California, USA: University of California Press. pp. 20, 37. ISBN 0-520-06697-9.

- ↑ Chris Gray, Conceptions of History in the Works of Cheikh Anta Diop and Theophile Obenga, (Karnak House:1989) 11–155

- ↑ Muḥammad Jamāl al-Dīn Mukhtār. Ancient Civilizations of Africa. Books.google.co.za. p. 33. Retrieved 2016-05-28.

- ↑ Alain Ricard, Naomi Morgan, The Languages & Literatures of Africa: The Sands of Babel, James Currey, 2004, p.14

- ↑ Mokhtar, G. (1990). General History of Africa. California, USA: University of California Press. p. 31. ISBN 0-520-06697-9.

- ↑ Muḥammad Jamāl al-Dīn Mukhtār. Ancient Civilizations of Africa. Books.google.co.za. p. 10. Retrieved 2016-05-28.

- 1 2 Muḥammad Jamāl al-Dīn Mukhtār. Ancient Civilizations of Africa. Books.google.co.za. p. 10. Retrieved 2016-05-28.

- ↑ Diop, Cheikh Anta (1974). The African Origin of Civilization. Chicago, Illinois: Lawrence Hill Books. pp. 112, 135–138. ISBN 1-55652-072-7.

- 1 2 Bailey, Susan (1996). Egypt in Africa. Indiana, USA: Indianapolis Museum of Art. pp. 88–89. ISBN 0-253-33269-9.

- 1 2 Stouhal, Eugen (1992). Life of the Ancient Egyptians. Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press. p. 29. ISBN 978-977-424-285-4.

- ↑ Ghalioungui, Paul (1963). Magic & Medical Science in Ancient Egypt. New York: Barnes & Noble. p. 95. ASIN B000IP45Z8.

- ↑ Stracmans, M. (1959). Encore un texte peau connu relatif a la circoncision des anciens Egyptiens. Archivo Internazionale di Ethnografia e Preistoria. pp. 2:7–15.

- ↑ Doyle D (October 2005). "Ritual male circumcision: a brief history" (PDF). The journal of the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh. 35 (3): 279–285. PMID 16402509.

- ↑ Goldenberg, David M. (2005). The Curse of Ham: Race and Slavery in Early Judaism, Christianity, and Islam (New ed.). Princeton University Press. p. 144. ISBN 978-0691123707.

- ↑ Diop, Cheikh Anta (1974). The African Origin of Civilization. Chicago, Illinois: Lawrence Hill Books. pp. 5–9. ISBN 1-55652-072-7.

- ↑ Levine, Molly Myerowitz (2004). "David M. Goldenberg, The Curse of Ham: Race and Slavery in Early Judaism, Christianity, and Islam.". Bryn Mawr Classical Review. Retrieved 4 February 2013.

- ↑ Mokhtar, G. (1990). General History of Africa. California, USA: University of California Press. pp. 27, 38, 40. ISBN 0-520-06697-9.

- ↑ Mokhtar, G. (1990). General History of Africa II: Ancient Civilizations of Africa. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. p. 27. ISBN 0-520-06697-9.

- ↑ Diop, Cheikh Anta (1974). The African Origin of Civilization. Chicago, Illinois: Lawrence Hill Books. pp. 246–248. ISBN 1-55652-072-7.

- 1 2 3 4 Shavit 2001: 148

- ↑ Aboubacry Moussa Lam, "L'Égypte ancienne et l'Afrique", in Maria R. Turano et Paul Vandepitte, Pour une histoire de l'Afrique, 2003, pp. 50 &51

- ↑ Herodotus (2003). The Histories. London, England: Penguin Books. pp. 134–135, 640. ISBN 978-0-14-044908-2.

- ↑ Bard, Kathryn A. "Ancient Egyptians and the Issue of Race". in Lefkowitz and MacLean rogers, p. 114

- ↑ Kemp, Barry J. (2006). Ancient Egypt: Anatomy Of A Civilization. Routledge. p. 21. ISBN 978-0-415-06346-3.

- ↑ Raymond Faulkner, A Concise Dictionary of Middle Egyptian, Oxford: Griffith Institute, 2002, p. 286.

- ↑ Gardiner, Alan (1957) [1927]. Egyptian Grammar: Being an Introduction to the Study of Hieroglyphs (3 ed.). Griffith Institute, Oxford. ISBN 0-900416-35-1.

- ↑ Mokhtar, G. (1990). General History of Africa. California, USA: University of California Press. p. 40. ISBN 0-520-06697-9.

- ↑ "Nubia Gallery". The Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago.

- ↑ Emberling, Geoff (2011). Nubia: Ancient Kingdoms of Africa. New York, NY: The Institute for the Study of the Ancient World. pp. 22–23, 36–37. ISBN 978-0-615-48102-9.

- ↑ Muḥammad Jamāl al-Dīn Mukhtār. Ancient Civilizations of Africa. Books.google.co.za. p. 10. Retrieved 2016-05-28.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on February 7, 2009. Retrieved February 9, 2009.

- ↑ Charlotte Booth,The Ancient Egyptians for Dummies (2007) p. 217

- 1 2 'Egypt, Trunk of the Tree, A Modern Survey of an Ancient Land, Vol. 2. by Simson Najovits pg 318

- ↑ Diop, Cheikh Anta (1974). The African Origin of Civilization. Chicago, Illinois: Lawrence Hill Books. pp. 6–42. ISBN 1-55652-072-7.

- ↑ W. E. B. Du Bois. The Negro. Books.google.co.uk. Retrieved 2016-05-28.

- ↑ Black man of the Nile and his family, by Yosef Ben-Jochannan, pp. 109–110

- ↑ Asante, Molefi Kete (1996). European Racism Regarding Ancient Egypt: Egypt in Africa. Indianapolis, Indiana: Indiana University Press. p. 117. ISBN 0-936260-64-5.

- ↑ Diop, Cheikh Anta (1974). The African Origin of Civilization. Chicago, Illinois: Lawrence Hill Books. pp. 27, 43. ISBN 978-1-55652-072-3.

- ↑ Diop, Cheikh Anta (1974). The African Origin of Civilization. Chicago, Illinois: Lawrence Hill Books. p. 27. ISBN 978-1-55652-072-3.

- ↑ Constantin-François Chassebœuf saw the Sphinx as "typically negro in all its features"; Volney, Constantin-François de Chasseboeuf, Voyage en Egypte et en Syrie, Paris, 1825, page 65

- ↑ "...its head is grey, ears very large and protruding like a negro’s...the fact that the nose is missing increases the flat, negroid effect. Besides, it was certainly Ethiopian; the lips are thick.." Flaubert, Gustave. Flaubert in Egypt, ed. Francis Steegmuller. (London: Penguin Classics, 1996). ISBN 978-0-14-043582-5.

- ↑ Hassan, Selim (1949). The Sphinx: Its history in the light of recent excavations. Cairo: Government Press, 1949.

- ↑ Williams, Bruce (2011). Before the Pyramids. Chicago, Illinois: Oriental Institute Museum Publications. pp. 89–90. ISBN 978-1-885923-82-0.

- ↑ "The Nubia Salvage Project".

- ↑ Ancient Egyptian Kingship. Books.google.co.za. Retrieved 2016-05-28.

- ↑ Diop, Cheikh Anta (1991). Civilization or Barbarism. Chicago, Illinois, USA: Lawrence Hill Books. pp. 103–105. ISBN 1-55652-048-4.

- ↑ O'Connor, David (2011). Before the Pyramids. Chicago, Illinois: Oriental Institute Museum Publications. pp. 162–163. ISBN 978-1-885923-82-0.

- ↑ "The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt". Books.google.co.za. 2003-10-23. p. 63. Retrieved 2016-05-28.

- ↑ D. Wengrow (2006-05-25). The Archaeology of Early Egypt: Social Transformations in North-East Africa ... Books.google.co.za. p. 167. Retrieved 2016-05-28.

- ↑ Peter Mitchell. African Connections: An Archaeological Perspective on Africa and the Wider World. Books.google.co.za. p. 69. Retrieved 2016-05-28.

- ↑ Archived copy. Retrieved January 27, 2013.

- ↑ László Török. Between Two Worlds: The Frontier Region Between Ancient Nubia and Egypt ... Books.google.co.za. p. 577. Retrieved 2016-05-28.

- ↑ Daily Life of the Nubians. Books.google.com. Retrieved 2016-05-28.

- ↑ An Introduction to the Archaeology of Ancient Egypt, by Kathryn A. Bard, 2015, p. 110

References

- Mary R. Lefkowitz: "Ancient History, Modern Myths", originally printed in The New Republic, 1992. Reprinted with revisions as part of the essay collection Black Athena Revisited, 1996.

- Kathryn A. Bard: "Ancient Egyptians and the issue of Race", Bostonia Magazine, 1992: later part of Black Athena Revisited, 1996.

- Frank M. Snowden, Jr.: "Bernal's "Blacks" and the Afrocentrists", Black Athena Revisited, 1996.

- Joyce Tyldesley: "Cleopatra, Last Queen of Egypt", Profile Books Ltd, 2008.

- Alain Froment, 1994. "Race et Histoire: La recomposition ideologique de l'image des Egyptiens anciens." Journal des Africanistes 64:37–64. available online: Race et Histoire (French)

- Yaacov Shavit, 2001: History in Black. African-Americans in Search of an Ancient Past, Frank Cass Publishers

- Anthony Noguera, 1976. How African Was Egypt?: A Comparative Study of Ancient Egyptian and Black African Cultures. Illustrations by Joelle Noguera. New York: Vantage Press.

- Shomarka Keita: "The Geographical Origins and Population Relationships of Early Ancient Egyptians", Egypt in Africa, (1996), pp. 25–27