Black Betty

| "Black Betty" | |

|---|---|

| Song by Lead Belly | |

| Released | 1939 |

| Genre | Work song, marching song, military cadence |

| Length | 1:55 |

| Label | Musicraft |

| Writer(s) | Traditional |

| "Black Betty" | |

|---|---|

| |

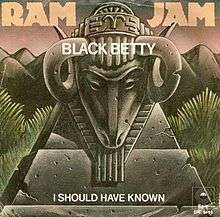

| Single by Ram Jam | |

| from the album Ram Jam | |

| B-side | "I Should Have Known" |

| Released | June 1977 |

| Format | 7-inch single |

| Genre | Hard rock, blues rock |

| Length | 2:32 (single) |

| Label | Epic |

| Writer(s) | Traditional, Huddie Ledbetter |

| "Black Betty" | |

|---|---|

| |

| Single by Tom Jones | |

| from the album Mr. Jones | |

| Released | November 2002 |

| Format | CD single |

| Genre | Pop rock |

| Length | 3:10 |

| Label | V2 |

| Producer(s) | Wyclef Jean, Jerry Duplessis |

| "Black Betty" | |

|---|---|

| |

| Single by Spiderbait | |

| from the album Tonight Alright | |

| Released | February 2004 |

| Format | CD single, Digital download |

| Genre | Hard rock, alternative rock |

| Length | 3:26 |

| Label | Universal Music (AUS), Interscope Records (US) |

| Producer(s) | Sylvia Massy |

"Black Betty" (Roud 11668) is a 20th-century African-American work song often credited to Huddie "Lead Belly" Ledbetter as the author, though the earliest recordings are not by him. Some sources claim it is one of Lead Belly's many adaptations of earlier folk material;[1] in this case an 18th-century marching cadence about a flintlock musket. There are numerous recorded versions, including a cappella, folk, and rock arrangements. The best known modern recordings are rock versions by Ram Jam, Tom Jones, and Spiderbait, all of which were hits.

Meaning and origin

The origin and meaning of the lyrics are subject to debate. Historically the "Black Betty" of the title may refer to the nickname given to a number of objects: a musket, a bottle of whiskey, a whip, or a penitentiary transfer wagon.

Some sources claim the song is derived from an 18th-century marching cadence about a flint-lock musket with a black painted stock; the "bam-ba-lam" lyric referring to the sound of the gunfire. In the British Army from the early 18th century the standard musket had a walnut stock, and was thus known (by at least 1785) as a 'Brown Bess'. [2] There is no citation however for this firearm or a subsequent model being known as a 'Black Betty'.

Other sources give the meaning of "Black Betty" in the United States (from at least 1827) as a liquor bottle.[3][4] In January 1736, Benjamin Franklin published The Drinker's Dictionary in the Pennsylvania Gazette offering 228 round-about phrases for being drunk. One of those phrases is "He's kiss'd black Betty."[5][6]

"Black Betty" used as an expression for a liquor bottle may ultimately owe its origin to the famous pretty black barmaid who worked at the notorious Tom King's Coffee House in Covent Garden, London, which opened in 1720.

In Caldwells's Illustrated Combination Centennial Atlas of Washington Co. Pennsylvania of 1876, a short section describes wedding ceremonies and marriage customs, including a wedding tradition where two young men from the bridegroom procession were challenged to run for a bottle of whiskey. This challenge was usually given when the bridegroom party was about a mile from the destination-home where the ceremony was to be had. Upon securing the prize, referred to as "Black Betty", the winner of the race would bring the bottle back to the bridegroom and his party. The whiskey was offered to the bridegroom first and then successively to each of the groom's friends.[7]

David Hackett Fischer, in his book Albion's Seed: Four British Folkways in America (Oxford University Press, 1989), states that "Black Betty" was a common term for a bottle of whisky in the borderlands of northern England/southern Scotland, and later in the backcountry areas of the eastern United States.

In 1934, John A. and Alan Lomax in their book, American Ballads and Folk Songs described the origins of "Black Betty":

| "Black Betty is not another Frankie, nor yet a two-timing woman that a man can moan his blues about. She is the whip that was and is used in some Southern prisons. A convict on the Darrington State Farm in Texas, where, by the way, whipping has been practically discontinued, laughed at Black Betty and mimicked her conversation in the following song." (In the text, the music notation and lyrics follow.)[8] |

John Lomax also interviewed blues musician James Baker (better known as "Iron Head") in 1934, almost one year after recording Iron Head performing the first known recording of the song.[9] In the resulting article for Musical Quarterly, titled "'Sinful Songs' of the Southern Negro", Lomax again mentions the nickname of the bullwhip is "Black Betty".[10] Steven Cornelius in his book, Music of the Civil War Era, states in a section concerning folk music following the war's end that "prisoners sang of 'Black Betty', the driver's whip."[11]

In an interview[12] conducted by Alan Lomax with a former prisoner of the Texas penal farm named Doc Reese (aka "Big Head"), Reese stated that the term "Black Betty" was used by prisoners to refer to the "Black Maria" — the penitentiary transfer wagon.

Robert Vells, in Life Flows On in Endless Song: Folk Songs and American History, writes:

| "As late as the 1960s, the vehicle that carried men to prison was known as "Black Betty," though the same name may have also been used for the whip that so often was laid on the prisoners' backs, "bam-ba-lam."[13] |

In later versions, "Black Betty" was depicted as various vehicles, including a motorcycle and a hot rod.

Black Betty is the slang name given to the Queen of Spades in the card game Hearts.

Early recordings, 1933–39

The song was first recorded in the field by U.S. musicologists John and Alan Lomax in 1933, performed a cappella by the convict James Baker and a group at Central State Farm, Sugar Land, Texas (a State prison farm).[14]

The Lomaxes were recording for the Library of Congress and later field recordings in 1934, 1936, and 1939 also include versions of "Black Betty". A notated version was published in 1934 in the Lomaxes book American Ballads and Folk Songs. It was recorded commercially in New York in 1939 for the Musicraft label by Lead Belly, as part of a medley with two other work songs: "Looky Looky Yonder" and "Yellow Woman's Doorbells". Musicraft issued the recording in 1939 as part of a 78rpm five-disc album entitled Negro Sinful Songs sung by Lead Belly.[15] Lead Belly had a long association with the Lomaxes, and had himself served time in State prison farms.

Post-1939

While Lead Belly's 1939 recording was also performed a cappella, most subsequent versions added a guitar accompaniment. These include folk-style recordings in 1964 by Odetta (as a medley with "Looky Yonder"), Dave "Snaker" Ray,[16] and Alan Lomax himself.[17]

In 1968 Manfred Mann released a version of the song with the title and lyrics changed to "Big Betty", on their LP Mighty Garvey. In 1972 Manfred Mann's Earth Band performed "Black Betty" live for John Peel's In Concert on the BBC, but this has not been publicly released.[18]

In 1976 a Cincinnati band, Starstruck, recorded a rock version of the song with modified lyrics on the Truckstar label which had little success.

Ram Jam version

In 1977, the rock band Ram Jam—which included former Starstruck and Lemon Pipers guitarist Bill Bartlett—re-released an edit of the Starstruck recording of the song with producers Jerry Kasenetz and Jeff Katz under Epic Records. The song became an instant hit with listeners, as it reached number 18 on the singles charts in the United States and the top ten in the UK and Australia. At the same time, the lyrics caused civil rights groups NAACP and Congress of Racial Equality to call for a boycott.[19]

Chart performance

Weekly charts

|

Year-end charts

|

Spiderbait version

"Black Betty" was the first single released from Spiderbait's album Tonight Alright, released in 2004. Produced by Sylvia Massy, this version is a slightly faster re-working of Ram Jam's hard rock arrangement.

The song was a hit in Australia, reaching number 1 on the ARIA Charts in May 2004, becoming Spiderbait's first number one single on this chart. The song also made an impression in the United States, reaching number 32 on Billboard's Mainstream Rock Songs chart in November of the same year. "Black Betty" was also featured in the movie Without A Paddle and Electronic Arts's 2004 game Need for Speed: Underground 2.

Chart performance

Weekly charts

Other notable versionsIn 2006 the University of New Hampshire administration controversially banned the playing of Ram Jam's "Black Betty" at UNH Hockey games. UNH Athletic Director Marty Scarano explained the reason for the decision: "UNH is not going to stand for something that insults any segment of society".[23] In 2006 UNH students started the "Save Black Betty" campaign. Students protested at the hockey games by singing Ram Jam's "Black Betty", wearing T-shirts that were blue with white writing on the front "Save Black Betty" and white writing on the back "Bam-A-Lam", and holding up campaign posters at the game. The Ram Jam version was again played once at a UNH/UMaine hockey game on January 24, 2013 after a seven-year hiatus. Selected list of recorded versions

Fleetwood Mac take-offOn Fleetwood Mac's 2003 album Say You Will, guitarist Lindsey Buckingham extensively quoted the chorus of "Black Betty" for his song "Murrow Turning Over in His Grave," an attack on the contemporary news media. For the "Black Betty had a child" line, Buckingham substituted the name of the reporter Ed Murrow. See alsoReferences

Bibliography

External links

|