Birds in culture

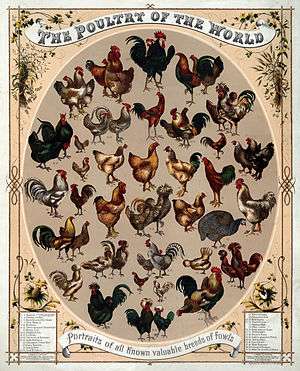

Birds have appeared in culture for thousands of years. They have been captured or bred as poultry for use as food. Raptors have been used in falconry, often to catch other birds, whether for pleasure or for food. They have been kept as cagebirds for their song, or raised for traditional sports such as cockfighting and pigeon racing.

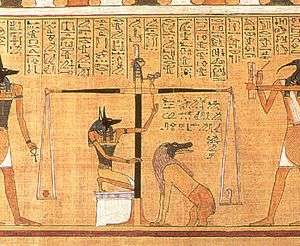

Birds have been depicted in paintings, sculpture, poetry and prose, music, ballet, and films such as Hitchcock's The Birds. Birds have appeared in mythology and religion from the time of Ancient Egypt, where the sacred ibis was venerated as a symbol of the god Thoth.

Their feathers have been used as adornments, whether for the headdresses of tribal peoples or the hats and boas of fashionable ladies. Today, millions of people enjoy birdwatching, and many put out birdfeeders to attract birds to their houses and gardens. Birds such as canaries and parrots are popular pets.

As food

Birds have for at least four thousand years been bred as poultry for use as food. The most important species is the chicken, providing some 20% of the animal protein eaten by the world's human population. However, Ducks, geese, pheasants, guineafowl and turkeys are all significant economically around the world.[1] Less commonly-raised species such as the ostrich are starting to be farmed for their meat, which is low in cholesterol; they have also been kept for their feathers, and for leather from their skin.[2]

Ducks such as mallard, wigeon, shoveler and teal have for centuries been captured by wildfowlers, while pheasants, partridges, grouse, and snipe are among the terrestrial birds that are hunted for sport.[3]

For enjoyment

Raptors from eagles to small falcons have for centuries been used in falconry, often to catch other birds, whether for pleasure or for food.[4]

Cockfighting, banned in many countries in the twentieth century on grounds of cruelty, is an ancient spectator sport. It formed part of the culture of the ancient Indians, Chinese, Greeks, and Romans. It continues to be practised in South America and across South and Southeast Asia, often combined with betting on the result.[5][6] It is practised in religious ceremonies in Hindu temples in Bali.[7]

Cagebirds such as the domestic canary are kept for their song, while parrots are kept as colourful pets, with the ability to mimic speech.[8][9]

Birdwatching has since the nineteenth century become a major leisure activity.[10][11] The British Royal Society for the Protection of Birds, founded in 1889, has grown to have over a million members; it has been followed by similar societies in other countries.[12]

Many people put out birdfeeders to attract birds to their gardens or windowsills.[13][14]

In the arts

Birds have been depicted throughout the arts, including in painting and sculpture, in literature, in music, in theatre, in ballet, and in film.

Birds have been depicted in paintings, sculptures and other art objects from the earliest times, including in cave paintings.[15] John James Audubon's images of birds in his 1827–1838 Birds of America are among the most admired.[16] In modern art, some of the paintings of Joan Miró include "A tangle of lines and small, colored ideograms suggesting birds, allegorical characters, stars, and animals".[17][18] In modern sculpture, Pablo Picasso's 1932 bronze Coq (Cockerel) is an assemblage of "spiky, elongated forms."[19]

In public statuary, the Magyars's mythical Turul symbolises national power and nobility, and is represented by many statues in Hungary, including the largest bird statue in the world, on a mountain near Tatabánya.[20][21][22]

In poetry, the 1177 Persian poem "The Conference of the Birds", the birds of the world assemble under the wisest bird, the hoopoe, to decide who is to be their king.[23] In English poetry, John Keats's 1819 "Ode to a Nightingale" and Percy Bysshe Shelley's 1820 "To a Skylark" are popular classics.[24][25] Bird poems by Gerard Manley Hopkins include "Sea and Skylark" and "The Windhover".[26] Ted Hughes's 1970 collection of poems about a bird character, "Crow", is considered one of his most important works.[27] English-language poems about birds have been have been anthologized in "Bright Wings" illustrated by David Allen Sibley and edited by Billy Collins.[28]

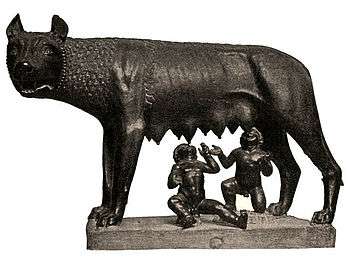

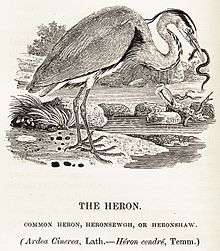

Birds have appeared in literature from ancient times. Among Aesop's Fables are The Wolf and the Crane[29] and The Fox and the Stork.[30] Thomas Bewick's 1797–1804 A History of British Birds brought affordable illustrations to the public for the first time, and the book formed in effect the first field guide to birds.[31] Beatrix Potter's 1908 The Tale of Jemima Puddle-duck created a popular bird character.[32]

In music, birdsong has influenced composers and musicians in several ways: they can be inspired by birdsong; they can intentionally imitate bird song in a composition, as Vivaldi and Beethoven did, along with many later composers; they can incorporate recordings of birds into their works, as Ottorino Respighi first did; or like Beatrice Harrison and David Rothenberg, they can duet with birds.[33][34][35]

In theatre, Aristophanes's 414 BC comedy The Birds (Greek: Ὄρνιθες Ornithes) is an acclaimed fantasy with effective mimicry of birds. The play's chorus consists of characters playing the partridge, francolin, mallard, kingfisher, sparrow, owl, jay, turtledove, crested lark, reed warbler, wheatear, pigeon, merlin, sparrowhawk, ringdove, cuckoo, stock dove, firecrest, rail, kestrel, dabchick, waxwing, vulture, woodpecker. There are also three bird messengers, some bird dancers, a hoopoe, a raven piper and a nightingale flute player in the cast, while several Athenians are compared to specific birds.[36][37]

In ballet, Tchaikovsky's classical 1895 Swan Lake and Igor Stravinsky's 1910 The Firebird have central bird characters.[38]

In film, Alfred Hitchcock's acclaimed 1963 The Birds, loosely based on Daphne du Maurier's story of the same name, tells the tale of sudden attacks on people by violent flocks of birds.[39] Ken Loach's much admired[40] 1969 Kes, based on Barry Hines's 1968 novel A Kestrel for a Knave, tells the story of a young boy who comes of age by training a kestrel that he has taken from the nest.[40]

In mythology and religion

Birds have appeared in mythology and religion from the time of Ancient Egypt, where the sacred ibis was venerated as a symbol of the god Thoth.[41] In Ancient Greece, Athens and Athena, Athens' patron goddess and the goddess of wisdom, had a little owl as her symbol.[42] In Medieval Christian iconography, the cormorant's "wing-drying" pose represents the Christian cross, and hence is a figure of Christ. In John Milton's Paradise Lost, on the other hand, the bird's cross-like pose is a travesty of Christ: "Then up he flew, and... Sat like a cormorant; yet not true life Thereby regained, but sat devising death To them who lived".[43][44]

In India, the peacock is perceived as Mother Earth among Dravidian peoples,[45] while the Mughal and Persian emperors displayed their godlike authority by sitting in a Peacock Throne.[46] In the Yazidi religion, Melek Taus the "Peacock Angel" is the central figure of their faith.[47]

Among the Parsees of India and Iran, and among other peoples, often practitioners of Vajrayana Buddhism who believe in the transmigration of souls in Sikkim, Mongolia, Bhutan and Nepal, sky burial has been practised for centuries. In this ritual, corpses are left exposed for griffon vultures to pick clean.[48]

In the cult of Makemake, the Tangata manu birds of Easter Island served as chiefs.[49] In Norse mythology, Hugin and Munin were ravens who whispered news into the ears of the god Odin.[50] In the Etruscan and Roman religions of ancient Italy, priests were involved in augury, interpreting the words of birds while the "auspex" watched their activities to foretell events.[51]

In the Inca and Tiwanaku empires of South America, birds are depicted transgressing the boundaries between the earthly and underground spiritual realms.[52] Indigenous peoples of the central Andes maintain legends of birds passing to and from metaphysical worlds.[53] The mythical chullumpi bird is said to mark the existence of a portal between such worlds, and to transform itself into a llama.[53][54]

In mythology, birds were sometimes monsters, like the Roc and the Māori's Pouākai, a giant bird capable of snatching humans.[55]

In clothing and fashion

_-_Gallica.jpg)

Elaborate, brightly-coloured headdresses containing feathers are worn by indigenous peoples of the Americas such as the Bororo of the Mato Grosso.[56]

In Western culture, feathers are used in boas, fashion accessories worn like long thin scarves.[57] Formerly, feathers were more widely used in fashion, decorating elaborate hats and other items of ladies' clothing.[58]

To find carcasses

The archaeological and historical records suggest interdependence between humans and vultures for millions of years. Like other animal species, early hominins probably used these birds as beacons signalling the location of meat, in the form of carcasses, in the landscape.[59]

To find honey

The greater honeyguide, a bird in the woodpecker order, guides people in some parts of Africa to the nests of wild bees.[60] A guiding bird attracts a person's attention with wavering, chattering "'tya' notes compounded with peeps or pipes".[61] The guiding bird flies a short distance with a conspicuous bounding, upward flight toward one of the many occupied bees' nests that it knows about in its territory. It then stops and calls again, spreading its tail which is conspicuously marked with white spots. When the native honey-hunter reaches the nest, he incapacitate the adult bees with smoke and open the nest with an axe or machete. When the humans have taken their honey, the honeyguide eats whatever is left.[62]

When the Boran people of East Africa follow a honeyguide, this reduces their search time for honey by approximately two-thirds. Because of this, the Boran use a specific loud whistle, known as the fuulido, when a search for honey is about to begin. The fuulido doubles the encounter rate with honeyguides.[60]

The Bushmen of the Kalahari have a tradition that the honeyguide must be thanked with a gift of honey; if not, it may lead its follower to a lion, bull elephant, or venomous snake as punishment. However, "others maintain that honeycomb spoils the bird, and leave it to find its own bits of comb".[62]

Other uses

Feathers are used to make warm and soft bedding, including eiderdowns from the belly down of the eider duck, and winter clothing as they have high "loft", trapping a large amount of air for their weight.[63] Feathers were used also for quill pens,[64] for fletching arrows,[65] and to decorate fishing lures.[66]

Bird bones were used by stone age peoples to make awls and other tools.[67] Guano, the droppings of seabirds, rich in nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium, was once important as an agricultural fertiliser and is still used in organic farming.[68] The War of the Pacific in 1865 was in part about control of guano sources.[69] Today, the chicken is used as a model organism in biological research.[70]

Cormorant fishing is a traditional fishing method in which fishermen use trained cormorants to fish in rivers. Historically, cormorant fishing has taken place in Japan and China since about 960 AD.[71]

Birds such as canaries, budgerigars, cockatoos, lovebirds, and parrots are popular pets, whether for their song, their behaviour, their colourful plumage, or their ability to imitate the human voice. Because they can be kept in cages, they are suitable for homes that might be too small or otherwise unsuitable for dogs or cats.[72][73] In 2013, there were estimated to be 1 million pet birds in Britain, and another million domestic fowls.[74] These estimates were revised down to 0.5 million pet birds and 0.7 million domestic fowls in 2015.[75]

As symbols

Birds have been seen as symbols, and used as such. In heraldry, birds, especially eagles, often appear in coats of arms.[76]

Also symbolically, over 3000 pubs in Britain have birds in their names and painted on their signs; their names include "Bird in Hand", "Bird & Babby", "Drunken Duck", "Eagle & Snake", "Halfmoon & Spread Eagle", "Jackdaw & Rook", "Wheatsheaf & Pigeon", and "White Swan & Cuckoo". Many pubs are named after a single bird, from "Albatross" and "Barn Owl" to "Woodcock", "Jenny Wren" and "Yellow Wagtail". Some familiar names with strong cultural associations are used many times: there are 24 pubs named "Crow's Nest" (nautical), 32 named "Dog & Duck" (wildfowling), 26 named "Eagle & Child" (heraldic), 129 named simply "Eagle", and 102 named "Falcon" (heraldic, or falconry). Especially popular is the mute swan, with 113 pubs named "Black Swan", 162 named "White Swan" and 362 simply called "The Swan".[77]

See also

References

- ↑ "History of Poultry". The Poultry Club of Great Britain. Retrieved 22 April 2016.

- ↑ Shanawany, M. M. "Recent developments in ostrich farming". Food and Agriculture Organization. Retrieved 22 April 2016.

- ↑ Marchington, John (1980). History of Wildfowling. A & C Black. ISBN 978-0-713-62053-5.

- ↑ "History of Falconry". The Falconry Centre. Retrieved 22 April 2016.

- ↑ Crews, Ed. "Once Popular and Socially Acceptable: Cockfighting". Colonial Williamsburg Foundation. Retrieved 22 April 2016.

- ↑ Lawler, Andrew (2 December 2014). "Birdmen. Cockfighters spread the chicken across the globe". Slate. Retrieved 22 April 2016.

- ↑ Cook, William (3 January 2015). "Cockfighting: the last, hidden link to Bali's warlike past". The Spectator. Retrieved 22 April 2016.

- ↑ "The Avicultural Society". The Avicultural Society. Retrieved 22 April 2016.

- ↑ Lane, Megan (16 September 2011). "How can birds teach each other to talk?". BBC News. Retrieved 25 September 2016.

- ↑ Dunne, Pete (2003). Pete Dunne on Bird Watching. Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0-395-90686-5.

- ↑ Oddie, Bill (1980). Bill Oddie's Little Black Bird Book. Butler & Tanner. ISBN 0-413-47820-3.

- ↑ "History of the RSPB". RSPB. Retrieved 19 February 2007.

- ↑ "Bird Feeding Basics". Audubon. 2004. Retrieved 22 April 2016.

- ↑ "Feeding birds". The Royal Society for the Protection of Birds. 3 November 2009. Retrieved 22 April 2016.

- ↑ Meighan, C. W. (1966). "Prehistoric Rock Paintings in Baja California". American Antiquity. 31 (3): 372–92. doi:10.2307/2694739. JSTOR 2694739.

- ↑ Smart, Alastair (23 May 2014). "The best birds in art". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 22 April 2016.

- ↑ "Woman Encircled by the Flight of a Bird, 1941 by Joan Miro". Joan Miro Paintings, Biography, and Quotes. Retrieved 22 April 2016.

- ↑ "Joan Miró Women and Bird in the Moonlight 1949". Tate Gallery. Retrieved 22 April 2016.

- ↑ "Pablo Picasso Cock 1932, cast 1952". Tate Gallery. Retrieved 22 April 2016.

- ↑ "Developing The Knowledge Economy: How Cities Help National Programs In Three Eu Accession And An Eca Country". The Economic Development Organization of the County Town Tatabánya. June 2002. Retrieved 22 April 2016.

- ↑ Warhol, Tom. Birdwatcher's Daily Companion: 365 Days of Advice, Insight, and Information for Enthusiastic Birders, Marcus Schneck, Quarry Books, 2010, p. 158

- ↑ István Dienes, The Hungarians cross the Carpathians, Corvina Press, 1972, p. 71

- ↑ Attar, Farid al-Din (1984). Darbandi, Afkham; Davis, Dick, eds. The Conference of the Birds. Penguin Classics. ISBN 978-0-14-044434-6.

- ↑ Brooks, Cleanth; Warren, Robert Penn (1968). Stillinger, Jack, ed. The Ode to a Nightingale. Keats's Odes. Prentice-Hall. pp. 44–47.

- ↑ Sandy, Mark (2002). "To a Skylark". The Literary Encyclopedia. Retrieved 22 April 2016.

- ↑ Hopkins, Gerard Manley (1985). Poems and Prose. Penguin Books. ISBN 9780140420159.

- ↑ "Crow – The Ted Hughes Society Journal". The Ted Hughes Society. 2012. Retrieved 22 April 2016.

- ↑ Collins, Billy (2010). Bright Wings. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-15084-2.

- ↑ "Aesop for Children (1919) 48. The Wolf and the Crane". Aesopica. Retrieved 23 April 2016.

- ↑ "Aesop for Children (1919) 48. THE FOX AND THE STORK". Aesopica. Retrieved 23 April 2016.

- ↑ Uglow, Jenny (14 October 2006). "Small wonders". The Guardian. Retrieved 12 January 2013.

- ↑ Taylor, Judy (1996) [1986]. Beatrix Potter: Artist, Storyteller and Countrywoman. Frederick Warne. p. 136. ISBN 0-7232-4175-9.

- ↑ Head, Matthew (1997). "Birdsong and the Origins of Music". Journal of the Royal Musical Association. 122 (1): 1–23. doi:10.1093/jrma/122.1.1.

- ↑ Clark, Suzannah (2001). Music Theory and Natural Order from the Renaissance to the Early Twentieth Century. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-77191-9.

- ↑ Reich, Ronni (15 October 2010). "NJIT professor finds nothing cuckoo in serenading our feathered friends". Star Ledger. Retrieved 19 June 2011.

- ↑ Aristophanes: The Birds and Other Plays. Barrett, D.; Sommerstein, A. Penguin Classics, 1978, page 149

- ↑ Greek Drama. Levi, Peter in 'The Oxford History of the Classical World'. Boardman, J.; Griffin, J.; Murray, O. (eds), Oxford University Press, 1986, page 178

- ↑ Wiley, Roland John. Tchaikovsky's Ballets: Swan Lake, Sleeping Beauty, Nutcracker. Oxford University Press 1985.

- ↑ Thompson, David (2008). 'Have You Seen…?' A Personal introduction to 1,000 Films. Knopf. p. 97. ISBN 978-0-375-71134-3.

- 1 2 "Kes (1969)". British Film Institute. Retrieved 22 April 2016.

- ↑ Wheye, Darryl; Kennedy, Donald (2008). Humans, Nature, and Birds: Science Art from Cave Walls to Computer Screens. Yale University Press. p. 36. ISBN 978-0-300-12388-3.

- ↑ Deacy, Susan; Villing, Alexandra (2001). Athena in the Classical World. Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands, ISBN 9004121420.

- ↑ Fowler, Alastair (2014). Milton: Paradise Lost. Routledge. pp. 227–228. ISBN 978-1-317-86573-5.

- ↑ Murphy-Hiscock, Arin (2012). Birds – A Spiritual Field Guide. Adams Media. pp. 48–49. ISBN 1-4405-2688-5.

- ↑ Thankappan Nair, P. (1974). "The Peacock Cult in Asia". Asian Folklore Studies. 33 (2): 93–170. doi:10.2307/1177550. JSTOR 1177550.

- ↑ Clarke, CP (1908). "A Pedestal of the Platform of the Peacock Throne". The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin. 3 (10): 182–83. doi:10.2307/3252550. JSTOR 3252550.

- ↑ "What is the Peacock Angel?". Retrieved 24 September 2016.

- ↑ van Dooren, Thom (May 2011). "Vultures and their People in India: Equity and Entanglement in a Time of Extinctions". Australian Humanities Review (50).

- ↑ Routledge, S.; Routledge, K. (1917). "The Bird Cult of Easter Island". Folklore. 28 (4): 337–55. doi:10.1080/0015587X.1917.9719006.

- ↑ Lukas, S.E.; Benedikt, R.; Mendelson, J.H.; Kouri, E.; Sholar, M.; Amass, L. (1992). "Marihuana attenuates the rise in plasma ethanol levels in human subjects". Neuropsychopharmacology. 7 (1): 77–81. PMID 1326277.

- ↑ Ingersoll, Ernest (1923). Archive.org, Birds in legend, fable and folklore. Longmans, Green, page 214

- ↑ Smith, S. (2011). "Generative landscapes: the step mountain motif in Tiwanaku iconography." (PDF). Ancient America. 12: 1–69.

- 1 2 Smith, S. (2011). "Generative landscapes: the step mountain motif in Tiwanaku iconography." (Automatic PDF download). Ancient America. 12: 1–69.

- ↑ Dransart, P. (2002). Earth, Water, Fleece and Fabric: An Ethnography and Archaeology of Andean Camelid Herding. Routledge. pp. 64, 79.

- ↑ Tennyson, A.; Martinson, P. (2006). Extinct Birds of New Zealand, Te Papa Press, Wellington ISBN 978-0-909010-21-8

- ↑ "Bororo Headdress". Indian-cultures.com. Retrieved 23 April 2016.

- ↑ "Feather Boa". Victoria and Albert Museum. Retrieved 22 April 2016.

- ↑ "Search the Collections: Feather hat". Victoria and Albert Museum. Retrieved 22 April 2016.

- ↑ Morelli, F.; Kubicka, A.; Tryjanowski, P.; Nelson, N. (2015). "The vulture in the sky and the hominin on the land: three million years of human-vulture interaction". Anthrozoos. 28 (3): 449–468. doi:10.1080/08927936.2015.1052279.

- 1 2 Isack, H. A.; Reyer, H.-U. (1989). "Honeyguides and honey gatherers: interspecific communication in a symbiotic relationship". Science. 243 (4896): 1343–1346. doi:10.1126/science.243.4896.1343. PMID 17808267.

- ↑ Short, Lester; Horne, Jennifer (2002). "Family Indicatoridae (Honeyguides)". In Josep Del Hoyo; Andrew Elliott; Jordi Sargatal. Handbook of the Birds of the World: Jacamars to Woodpeckers, Vol. 7. Lynx. ISBN 84-87334-37-7.

- 1 2 Short, Lester; Horne, Jennifer; Diamond, A. W. (2003). "honeyguides". In Christopher Perrins. Firefly Encyclopedia of Birds. Firefly Books. pp. 396–397. ISBN 1-55297-777-3.

- ↑ Bonser, R.H.C. & Dawson, C. (1999). "The structural mechanical properties of down feathers and biomimicking natural insulation materials". Journal of Materials Science Letters. 18 (21): 1769–1770. doi:10.1023/A:1006631328233.

- ↑ "The Quill Pen". Colonial Williamsburg Foundation. Retrieved 22 April 2016.

- ↑ Massey, Jim (1992). Hamm, Jim, ed. Self Arrows. The Traditional Bowyer's Bible Volume One. Lyons Press. ISBN 1-58574-085-3.

- ↑ Wakeford, Jacqueline (1992). Fly Tying Tools and Materials. Lyons & Burford. pp. Preface. ISBN 1-55821-183-7.

- ↑ "Bone Tools". University of Iowa Office of the State Archaeologist. Retrieved 22 April 2016.

- ↑ Cushman, Gregory T. (2013). Guano and the Opening of the Pacific World: A Global Ecological History. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge Univ. Press. ISBN 9781107004139.

- ↑ "The Guano War of 1865–1866". World History at KMLA. Retrieved 23 April 2016.

- ↑ Burt, D. W. (2007). "Emergence of the Chicken as a Model Organism: Implications for Agriculture and Biology". Poultry Science. 86 (7): 1460–1471. doi:10.1093/ps/86.7.1460. PMID 17575197.

- ↑ Jackson, C. E. (1997). "Fishing with cormorants". Archives of Natural History. 24 (2): 189–211. doi:10.3366/anh.1997.24.2.189.

- ↑ "Popular pet Birds". The Bird Channel. Retrieved 25 April 2016.

- ↑ Kalhagen, Alyson (25 November 2014). "Top Reasons Why a Bird Could Be the Best Choice for Your Family". Retrieved 25 April 2016.

- ↑ "Pet Population 2013". Pet Food Manufacturers' Association. Retrieved 25 April 2016.

- ↑ "Pet Population 2015". Pet Food Manufacturers' Association. Retrieved 25 April 2016.

- ↑ Fox-Davies, A. C. (1985). A Complete Guide to Heraldry. Bloomsbury.

- ↑ Cocker, Mark; Mabey, Richard (2005). Birds Britannica. Chatto & Windus. pp. 473–476. ISBN 0-7011-6907-9.

Further reading

- Cocker, Mark; Mabey, Richard (2005). Birds Britannica. Chatto & Windus. ISBN 0-7011-6907-9.