Big Pit National Coal Museum

| Pwll Mawr Amgueddfa Lofaol Cymru | |

| |

| Established | 1983 |

|---|---|

| Location | Blaenavon, Wales |

| Coordinates | 51°46′21″N 3°06′18″W / 51.7724°N 3.1050°W |

| Visitors | 144,813(2015)[1] |

| Website | www.museumwales.ac.uk/en/bigpit/ |

Big Pit National Coal Museum (Welsh: Pwll Mawr Amgueddfa Lofaol Cymru) is an industrial heritage museum in Blaenavon, Torfaen, South Wales. A working coal mine from 1880 to 1980, it was opened to the public in 1983 under the auspices of the National Museum of Wales. The site is dedicated to operational preservation of the Welsh heritage of coal mining, which took place during the Industrial revolution.

Located adjacent to the preserved Pontypool and Blaenavon Railway, Big Pit is part of the Blaenavon Industrial Landscape, a World Heritage Site, and an Anchor Point of the European Route of Industrial Heritage.

History of the working pit

Big Pit was originally an iron mine, driven into the side of the mountain not far from the surface due to the shallow iron deposits, the level is called Engine Pit Level and can still be seen on the bridge connecting Blaenavon and Garn Rd at 51.773998, -3.092075 coordinates. The Iron Workings are above the Big Pit coal workings, for some time Engine Pit Level was used as an emergency exit for Big Pit whilst it was working, now the River Arch Level is the escape route. Engine Pit Level was driven around 1810 by hand due to dynamite being invented 5 decades later, there are no known records of the iron mine, although none that I can find.There are a few pictures online showing the interior of the Engine Level from the 60's when miners from Big Pit explored the level, finding an old flange-less wheel'ed dram inside, now at a museum. There was also a known Iron Workings shaft, Engine Pit Shaft which existed, information and location of this shaft can be on Industrial Gwent.

The Big Pit is part of a network of coal workings established in Blaenavon in the first half of the nineteenth century by the Blanaevon Iron and Coal Company as part of the development of the Blaenavon Ironworks,[2][lower-alpha 1] which means it has some of the oldest large scale industrial coal mining developments in the South Wales Coalfield.[2] The mine was the most important of all the collieries located in Blaenavon.[3]

The nearby Coity pit is shown in reports in the 1850s,[2] consisting of two shafts 9 feet (2.7 m) in diameter which were difficult to pump out.[2] Historians disagree about when the Big Pit was first in consistent operation, but it may have been a development of a former pit called Kearsley's Pit mentioned in the company records from the 1860s, which lay at the other end of a geological fault from the Coity pits.[2][3][lower-alpha 2]

A mines inspector report of 1881 is the first to describe a mine called the Big Pit[2] due to its elliptical shape with dimensions of 18 feet (5.5 m) by 13 feet (4.0 m), the first shaft in Wales large enough to allow two tramways.[4] On completion it became the coal-winding shaft, while the older Coity shaft was used for upcast air ventilation.[5]

In 1878, the main shaft was deepened to reach the Old Coal seam at 293 feet (89 m). By 1908, Big Pit provided employment for 1,122 people, and by 1923 at peak, there were 1,399 men employed, producing: House Coal, Steam Coal, Ironstone and Fireclay; from the Horn, No. 2 Yard, Old Coal and Elled seams. The peak of production was more than 250,000 tons of coal per year.[6] During the height of production, coal from Big Pit was shipped as far as South America, and also to other points world-wide.[3][4] Until 1908, when a conveyor became part of the mine equipment, everything at Big Pit was done by man power-including cutting the coal.[4] The mine was one of the first to install electricity and by 1910, fans, hauling systems and pumps were electric powered.[4]

In 1939, pithead baths were installed at the mine; it meant miners no longer needed to walk home dirty and wet, risking illness. The baths were also beneficial to miners' families; women no longer needed to carry hot jugs of water to fill tin baths and children were no longer accidentally scalded during this process.[3][lower-alpha 3] During the Second World War, surface extraction of coal began at Blaenavon in November 1941 using equipment and skilled men from the Canadian Army.[7] On nationalisation in 1947, the National Coal Board took over the mine from the Blaenavon Co. Ltd,[8] which employed 789 men.

By 1970 the workforce only numbered 494, as operations had focused solely on the Garw seam, with a maximum thickness of only 30 inches (760 mm). The NCB agreed the development of a drift mine, which by 1973 meant that windings at Big Pit had ceased, with coal extracted close to the refurbished Black Lion coal washery.[9] The Coity shaft was abandoned, with the Big Pit shaft used for upcast air ventilation and emergency extraction.[9]

The pit finally closed on 2 February 1980 with a loss of more than 250 jobs;it was one of the last working coal mines in Blaenavon, leaving only the Johnson Mine, closing in 2013 and Blaentillery No.2 Drift Mine closing in 2010.[3][10]

Transport

In 1866, the Brynmawr and Blaenavon Railway opened, with access sidings to the mine workings. The line was immediately leased to the London and North Western Railway, allowing coal to be directly transported to the Midlands via the Merthyr, Tredegar and Abergavenny Railway.[11] By 1880, the line had extended south to meet the Great Western Railway at Abersychan & Talywain. Here the line carried on down the valley through Pontypool Crane Street railway station to the coast at Newport, and hence to overseas markets via Newport Docks. In 1922 the LNWR was grouped into the London, Midland and Scottish Railway.[12] From World War II onwards, the line saw a variety of GWR locomotives operating from pit to port, with the line losing its passenger operations from 1941. After other pits in the area had closed, the line connection north was closed as a result of the Beeching cuts from 1964 onwards. The NCB paid for the line to be re-extended to Waunavon in the early 1970s, where the drift mine developments accessed the refurbished former Black Lion coal washery.

Big Pit Halt railway station which is on the heritage Pontypool and Blaenavon Railway line, adjacent to the museum, officially opened on 6 April 2012,[13] however the line to Big Pit actually opened on Friday 16 September 2011.[14] The line and station opened specifically for tourists visiting the museum.[14]

Disasters

Between 1857 and 1880, more than 60 deaths were recorded by mine inspectors in the Blaenavon coal and ironworks, although these may not have been in the Big Pit itself.[2]

From 1880, there are regular reports of accidents at the Big Pit, often resulting in loss of life. In 1891 a boy called Thomas Oliver Jones was crushed to death in a roof fall.[15] In 1894[16] and 1896[17] two further miners lost their lives in fatal accidents.

On 11 December 1908 three men were killed in an explosion.[18] A coroner's court found that the explosion had been caused by a naked light held by one of the miners.[19] On 7 April 1913, another three men lost their lives in a localized fire[20] that included a fireman, the face manager, and the under manager.[21]

The National Coal Museum

For some years before closure, the mine had been identified as being a possible heritage attraction and a working group was set up made up of the National Coal Board, local government, the National Museum, the Welsh Development Agency and the Welsh Office.[10] Soon after the pit closed, Torfaen Borough Council bought the site for £1 and it was given to a charitable trust called the Big Pit (Blaenavon) Trust to manage the conversion to a heritage museum. The initial development cost £1.5 million with funding from the Welsh Tourist Board, the European Regional Development Fund, the borough council and Gwent County Council.[10] The mine reopened for visitors in 1983 and created 71 jobs.[10]

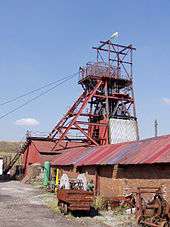

A number of buildings were subsequently given protected status at the site. The Powder House,[22] Saw mill[23] Office[24] Electrical Workshop,[25] Pit Head Building, Headframe and Tram Circuit,[26] and Miners' Bathhouse[27] were each given Grade II Listed Building status on 2 September 1995. The Powder House building was used to store explosives needed for mine work during the time Big Pit was an active mine.[22]

Big Pit as a tourist attraction

Initially visitor numbers were lower than expected which threatened the long term viability of the museum.[6] In 1983 less than 100,000 visitors came to the site and the numbers reached a peak of 120,000 in 1992.[6] Subsequently the visitor numbers reduced significantly to less than 90,000 in 1998.[6] The project plan at the start of the project suggested that 100,000 visitors were needed per year in the first 5 years.[6]

By 2000 it was clear that this was not being achieved and that the £5.75 adult entry fee was not covering costs.[6] A substantial Heritage Lottery Fund grant of more than £5 million was awarded in January 2000 which paid for a significant upgrade of the visitor facilities.[10] On 1 February 2001 it became incorporated into the National Museum Wales, was initially known as the National Mining Museum of Wales, and is now called Big Pit: National Coal Museum. As part of the National Museum Wales, the Big Pit became free to enter in 2001[28] and in 2015 First Minister Carwyn Jones announced that “there will be no payment for entry into any of the National Museums attractions"[29]

Since becoming part of the NMW, the museum has increased the numbers of visitors, with more than 140,000 visiting in 2014/15.[1] Intentionally preserved as an operational attraction, the site was redeveloped in 2003, with design work from TACP/Brooke Millar Partnership. The pit props and steel bands are not for show, but to hold up the mine roof. The water flowing down the tunnel towards the cages is real, apart from the fact it now flows down a channel rather than over the miners feet.

In 2005 it won the prestigious Gulbenkian Prize.[30][31]

The museum hired mining apprentices in 2011; after serving an apprenticeship, the trainees would then have the necessary qualifications to work in a mine.[32]

The museum features a range of above ground attractions including a winding house, saw mill, pithead, baths. Visitors are also taken below ground to the pit bottom where they tour the mine workings.[33] In 2000, the Blaenavon industrial area, including Big Pit National Coal Museum, was named a World Heritage Site by UNESCO. This was in recognition of the town's importance to the Industrial Revolution.[34] Museum staff walked out in disputes over pay in 2014,[35] 2015[36] and 2016.[37]

The Blaenavon Cheddar Company, a local cheese company, ages its Pwll Mawr (Big Pit) cheddar at the bottom of the Big Pit mine shaft.[4][38][39]

Safety

The mine is covered by HM Inspectorate of Mines regulations, because it is still classed as a working pit.[4] Visitors wear a plastic hard hat, safety lamp, and a battery on a waist belt which weighs 5 kilograms (11 lb). Visitors must also carry on their belt a rebreather, which in case of emergency will filter foul air for approximately one hour, giving a chance for survival and escape.[40]

Before taking the 50 minute underground tour 90 metres (300 ft) below ground, contraband must be surrendered, such as anything containing a dry cell battery from watches to mobile phones.[4] The dangers of the mine are real, the safety posters on the stages of Carbon Monoxide poisoning serve as museum pieces and as real reminders of the dangers underground. Automatic gas monitoring systems are discreetly positioned around the tunnels, as are emergency telephone systems. Some safety beams were monitored around the area.[40]

Popular culture

The cover of the Manic Street Preachers album National Treasures – The Complete Singles shows the Big Pit winding tower.[41]

Historian Gwyn A. Williams used the Big Pit as a setting for one of his programmes in his Channel 4 series The Dragon Has Two Tongues, broadcast in January 1985 - near the end of the miners' strike and as men were returning to work. In it, Williams said "Today it looks to me as if the Welsh people have been declared redundant, as redundant as this pit which after 200 years is now a museum. This is a museum. Wales is being turned into a land of museums!"[42]

See also

- Mining in Wales

- Mining accident

- South Wales coalfield

- South Wales Coalfield Collection

- 1926 United Kingdom general strike

- UK miners' strike (1984–85)

- Rhondda Heritage Park

- National Coal Mining Museum for England

- Rhymney

- Blaenavon

Notes

- ↑ The earlier mines supplied iron ore for the many ironworks in the area. Coal was mined here at the time for local demand. It was not until the latter part of the 19th century that there was a great demand for coal.[3]

- ↑ This was a consolidation of many smaller mines:Coity Pits, Dodd'e Slope, Coity Level, Blaenavon New Mine, Elled Drift, Forge Pit, Forge Slope and Forge Level. Forge Level was the oldest portion of the mine; activity began there in 1812.[3]

- ↑ Today the miners' baths building houses exhibits and a cafe.[4]

References

- 1 2 "Cumulative Visitor Figures 2015-2016". Amgueddfa Cymru — National Museum Wales. Retrieved 12 April 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Evans, JAH (2000). "Big Pit Blanaevon - a new chronology?". Gwent Local History. 88: 54.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Big Pit:A Brief History" (PDF). Visit Blaenavon.co.uk. Retrieved 13 April 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 McCrum, Kirstie (7 September 2013). "Going Underground; Big Pit: National Coal Museum Is Celebrating Its 30th Anniversary as a Tourist Attraction and Museum". Western Mail. Retrieved 14 June 2016 – via Questia. (subscription required (help)).

- ↑ Thomas, W. Gerwyn (1976). Welsh coal mines. National Museum of Wales. p. 45. Retrieved 13 April 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Wanhill, S. (2000). "Mines--A Tourist Attraction: Coal Mining in Industrial South Wales". Journal of Travel Research. 39 (1): 60–69. doi:10.1177/004728750003900108. ISSN 0047-2875.

- ↑ Michael Stratton; Barrie Trinder (4 April 2014). Twentieth Century Industrial Archaeology. Taylor & Francis. pp. 21–. ISBN 978-1-136-74801-1.

- ↑ "PIT HEAD BUILDING, HEADFRAME AND TRAM CIRCUIT, BIG PIT COAL MINE, BLAENAVON". Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales. Retrieved 13 April 2016.

- 1 2 "Gwent Archives Colliery photographs collection context". National Library of Wales. Retrieved 13 April 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Coupland, B (December 2012). "Heritage and Memory: Oral History and Mining Heritage in Wales and Cornwall - Doctoral Thesis" (PDF). Exeter University.

- ↑ "Brynmawr and Blaenavon Railway". Railscot.

- ↑ "History". London and North Western Society. Retrieved 15 June 2015.

- ↑ "Pontypool and Blaenavon Railway > PBR Easter Opening 2012". SmugMug, Inc. Retrieved 1 July 2012.

- 1 2 "Blaenavon railway opens line to Big Pit". South Wales Argus. Retrieved 1 July 2012.

- ↑ "BLAENAVON". David Duncan and Sons. South Wales Daily News. 16 August 1891. p. 3. Retrieved 13 April 2016.

- ↑ "BLAENAVON". David Duncan and Sons. South Wales Daily News. 2 April 1894. p. 6. Retrieved 13 April 2016.

- ↑ "BLAENLAVON". David Duncan and Sons. South Wales Daily News. 25 July 1896. p. 6. Retrieved 13 April 2016.

- ↑ "Pit Explosion". Walter Alfred Pearce. Evening Express. 11 December 1908. p. 3. Retrieved 15 April 2016.

- ↑ "Blaenavon Pit Explosion". Walter Alfred Pearce. Evening Express. 18 December 1918. p. 3. Retrieved 12 April 2016.

- ↑ "SUFFOCATED". Frederick Wicks. The Cambria Daily Leader. 8 April 1913. p. 3. Retrieved 13 April 2016.

- ↑ Alexander, Dick (9 June 1985). "Mining Wales` Big Pit For A Lode Of Memories". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved 13 April 2016.

- 1 2 "Powder House, Big Pit Mining Museum, Blaenavon". British Listed Building. Retrieved 14 April 2016.

- ↑ "Saw Mill, Big Pit Mining Museum, Blaenavon". British Listed Building. Retrieved 14 April 2016.

- ↑ "Office, Big Pit Mining Museum, Blaenavon". British Listed Building. Retrieved 14 April 2016.

- ↑ "Electrical Workshop, Big Pit Mining Museum, Blaenavon". British Listed Building. Retrieved 14 April 2016.

- ↑ "Pit Head Building, Headframe and Tram Circuit, Big Pit Mining Museum, Blaenavon". British Listed Building. Retrieved 14 April 2016.

- ↑ "Miners' Bath and Canteen, Big Pit Mining Museum, Blaenavon". British Listed Building. Retrieved 14 April 2016.

- ↑ "Museums launch free entry". BBC. 2001. Retrieved 12 April 2016.

- ↑ "Big Pit underground tours to stay free of charge - First Minister". South Wales Argus. 2015. Retrieved 12 April 2016.

- ↑ "Gulbenkian Prize for Museums and Galleries Winner 2005". Gulbenkian Prize. 2005. Retrieved 12 April 2016.

- ↑ Price, Karen (27 May 2005). "Cash at Old Coalface as Big Pit Wins Museum of the Year". Western Msil. Retrieved 15 June 2016 – via Questia. (subscription required (help)).

- ↑ "Big Pit mining museum at Blaenavon to seek apprentices". BBC News. 30 July 2011. Retrieved 14 April 2016.

- ↑ Michael V. Conlin; Lee Jolliffe (4 October 2010). Mining Heritage and Tourism: A Global Synthesis. Routledge. pp. 1–. ISBN 978-1-135-22906-1.

- ↑ "World Heritage Site Status". Blaenavon World Heritage Site. Retrieved 14 April 2016.

- ↑ "Three Welsh museums set to close over weekend as staff to walk out over pay row". Walesonline. 5 August 2014. Retrieved 12 April 2016.

- ↑ "Big Pit remains closed on day two of museum strikes". BBC. 30 August 2015. Retrieved 12 April 2016.

- ↑ "Four-day museum strike begins at Big Pit in Blaenavon". BBC. 25 March 2016. Retrieved 12 April 2016.

- ↑ "Blaenavon Cheddar Company". Retrieved 14 June 2016.

- ↑ "Products-Pwll Mawr-Blaenavon Cheddar Company". Retrieved 14 June 2016.

- 1 2 Maconie, Stuart (2015). The Pie At Night: In Search of the North at Play. Random House. p. 25. ISBN 978-1-4090-3324-0.

- ↑ Maconie, Stuart (2015). The Pie At Night: In Search of the North at Play. Random House. p. 24. ISBN 978-1-4090-3324-0.

- ↑ Ilse Josepha Lazaroms; Emily R. Gioielli (17 March 2016). The Politics of Contested Narratives: Biographical Approaches to Modern European History. Routledge. pp. 181–. ISBN 978-1-317-61541-5.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Big Pit National Coal Museum. |

- Official website of Big Pit National Coal Museum

- European Route of Industrial Heritage – Big Pit National Coal Museum

- Big Pit @ Welsh Coalmines

- BBC Wales Coal House on Coal history