Bezeklik Thousand Buddha Caves

| Bezeklik Caves | |

|---|---|

|

Bezeklik caves | |

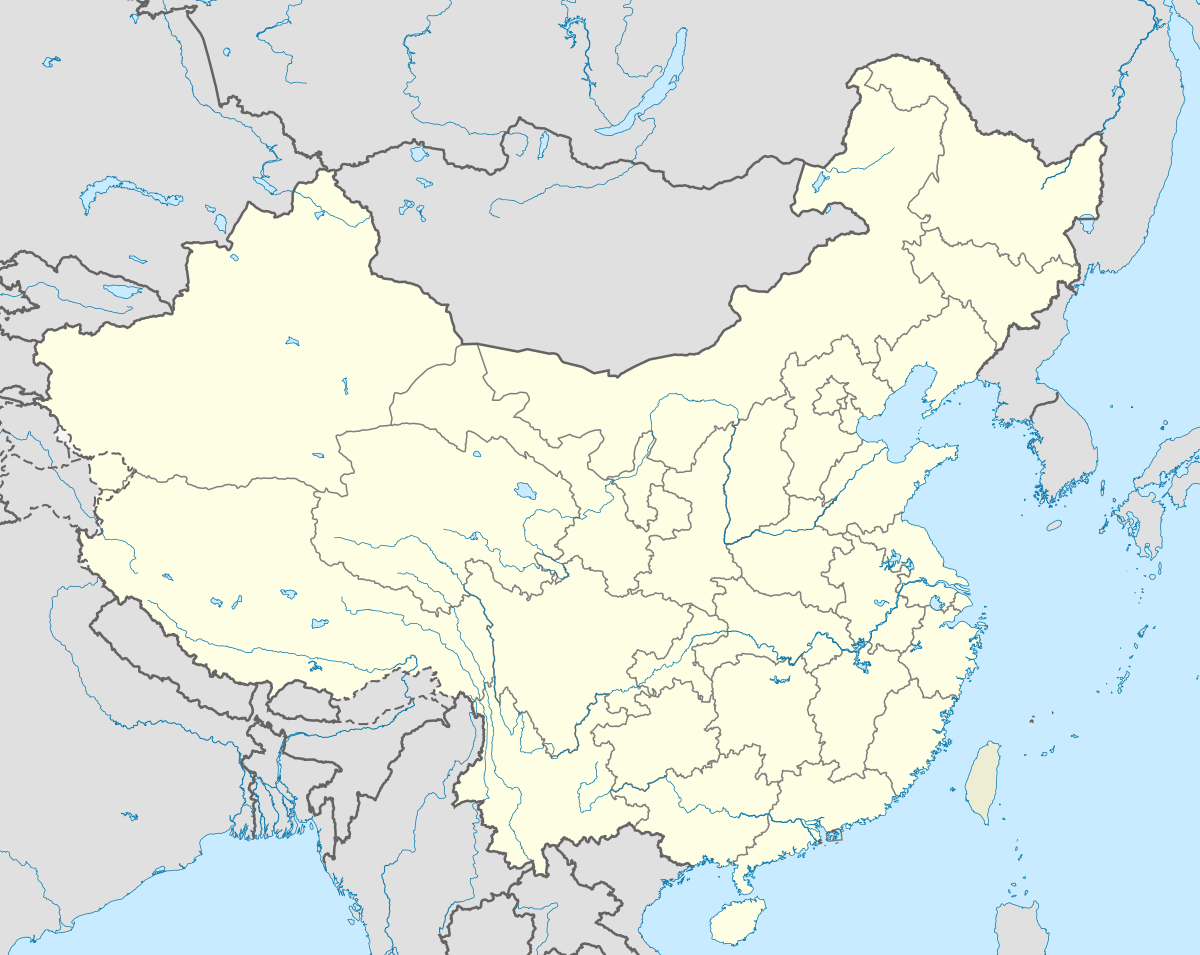

Location of Bezeklik Caves in China | |

| Coordinates | 42°57′21″N 89°32′22″E / 42.95583°N 89.53944°ECoordinates: 42°57′21″N 89°32′22″E / 42.95583°N 89.53944°E |

The Bezeklik Thousand Buddha Caves (Chinese: 柏孜克里千佛洞; pinyin: Bózīkèlǐ Qiānfódòng) is a complex of Buddhist cave grottos dating from the 5th to 14th century between the cities of Turpan and Shanshan (Loulan) at the north-east of the Taklamakan Desert near the ancient ruins of Gaochang in the Mutou Valley, a gorge in the Flaming Mountains, China. They are high on the cliffs of the west Mutou Valley under the Flaming Mountains,[1] and most of the surviving caves date from the West Uyghur kingdom around the 10th to 13th centuries.[2]

Bezeklik murals

There are 77 rock-cut caves at the site. Most have rectangular spaces with rounded arch ceilings often divided into four sections, each with a mural of the Buddha. The effect is of entire ceiling covers with hundreds of Buddha murals. Some murals show a large Buddha surrounded by other figures, including Turks, Indians and Europeans. The quality of the murals vary with some being artistically naive while others are masterpieces of religious art.[6] The murals that best represent the Bezeklik Thousand Buddha Caves are the large-sized murals, which were given the name the "Praņidhi Scene", paintings depicting Sakyamuni’s "promise" or "praņidhi" from his past life.[7]

Professor James A. Millward described the original Uyghurs as physically Mongoloid, giving as an example the images in Bezeklik at temple 9 of the Uyghur patrons, until they began to mix with the Tarim Basin's original Indo-European Tocharian inhabitants.[8] Buddhist Uyghurs created the Bezeklik murals.[9] However, Peter B. Golden writes that the Uyghurs not only adopted the writing system and religious faiths of the Indo-European Sogdians, such as Manichaeism, Buddhism, and Christianity, but also looked to the Sogdians as "mentors" while gradually replacing them in their roles as Silk Road traders and purveyors of culture.[10] Indeed, Sogdians wearing silk robes are seen in the praṇidhi scenes of Bezeklik murals, particularly Scene 6 from Temple 9 showing Sogdian donors to the Buddha.[4] The paintings of Bezeklik, while having a small amount of Indian influence, is primarily influenced by Chinese and Iranian styles, particularly Sasanian Persian landscape painting.[11] Albert von Le Coq was the first to study the murals and published his findings in 1913. He noted how in Scene 14 from Temple 9 one of the Caucasian-looking figures with green eyes, wearing a green fur-trimmed coat and presenting a bowl with what he assumed were bags of gold dust, wore a hat that he found reminiscent of the headgear of Sasanian Persian princes.[12]

The Buddhist Uyghurs of the Kingdom of Qocho and Turfan were converted to Islam by conquest during a ghazat (holy war) at the hands of the Muslim Chagatai Khanate ruler Khizr Khoja (r. 1389-1399).[13]

After being converted to Islam, the descendants of the previously Buddhist Uyghurs in Turfan failed to retain memory of their ancestral legacy and falsely believed that the "infidel Kalmuks" (Dzungars) were the ones who built Buddhist monuments in their area.[14][15]

Anti portrait Muslims had Buddhist portraits obliterated during the wars over hundreds of years in which Buddhism was replaced by Islam. Cherrypicking of history of Xinjiang with the intention of projecting an image of irreligiousity or piousness of Islam in Uyghur culture has been done by people with agendas.[16] Michael Dillon wrote that the 1000s-1100s Islam-Buddhist war are still recalled in the forms of the Khotan Imam Asim Sufi shrine celebration and other Sufi holy site celebrations. Bezeklik's Thousand Buddha Caves are an example of the religiously motivated vandalism against portraits of religious and human figures.[17]

The murals at Bezeklik have suffered considerable damage. Many of the murals were damaged by local Muslim population whose religion proscribed figurative images of sentient beings, the eyes and mouths in particular were often gouged out. Pieces of murals were also broken off for use as fertilizer by the locals.[18] During the late nineteen and early twentieth century, European and Japanese explorers found intact murals buried in sand, and many were removed and dispersed around the world. Some of the best preserved murals were removed by German explorer Albert von Le Coq and sent to Germany. Large pieces such as those showing Praņidhi scene were permanently fixed to walls in Museum of Ethnology in Berlin. During the Second World War they could not be removed for safekeeping, and were thus destroyed when the museum was caught in the bombing of Berlin by the Allies.[18] Other pieces may now be found in various museums around the world, such as the Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg, Tokyo National Museum in Japan, the British Museum in London, and the national museums of Korea and India.

A digital recreation of the Bezeklik murals removed by explorers was shown in Japan.[2][19]

Gallery

-

View on to the valley

-

.jpg)

View on caves

-

Closer view on caves

-

Frescoes of Buddhas

-

Frescoes of Buddhas

-

A Uyghur prince

-

Uyghur princesses, cave 9, Museum für Asiatische Kunst

-

Uyghur Princes wearing robes and headgears, cave 9.

-

An Indian brahmin figure from Cave 9, dated 8th-9th century AD, wall painting

-

-

Tradesmen, Tang dynasty

-

Uyghur woman from the Bezeklik murals

-

Uyghur noble from the Bezeklik murals

-

Uyghur noble from the Bezeklik murals

-

Uyghur donor from the Bezeklik murals

- ^ von Le Coq, Albert. (1913). Chotscho: Facsimile-Wiedergaben der Wichtigeren Funde der Ersten Königlich Preussischen Expedition nach Turfan in Ost-Turkistan. Berlin: Dietrich Reimer (Ernst Vohsen), im Auftrage der Gernalverwaltung der Königlichen Museen aus Mitteln des Baessler-Institutes, Tafel 19. (Accessed 3 September 2016).

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

gasparini_2014_pp134-163was invoked but never defined (see the help page).

See also

- Mogao Caves

- Kizil Caves

- Tianlongshan Grottoes

- Silk Road transmission of Buddhism

- German Turfan expeditions

Footnotes

- ↑ "Bizaklik Thousand Buddha Caves". travelchinaguide.com. Retrieved 2007-09-21.

- 1 2 Reconstruction of Bezeklik murals at Ryukoku Museum

- ↑ von Le Coq, Albert. (1913). Chotscho: Facsimile-Wiedergaben der Wichtigeren Funde der Ersten Königlich Preussischen Expedition nach Turfan in Ost-Turkistan. Berlin: Dietrich Reimer (Ernst Vohsen), im Auftrage der Gernalverwaltung der Königlichen Museen aus Mitteln des Baessler-Institutes, p. 28, Tafel 20. (Accessed 3 September 2016).

- 1 2 Gasparini, Mariachiara. "A Mathematic Expression of Art: Sino-Iranian and Uighur Textile Interactions and the Turfan Textile Collection in Berlin," in Rudolf G. Wagner and Monica Juneja (eds), Transcultural Studies, Ruprecht-Karls Universität Heidelberg, No 1 (2014), pp 134-163. ISSN 2191-6411. See also endnote #32. (Accessed 3 September 2016.)

- ↑ Hansen, Valerie (2012), The Silk Road: A New History, Oxford University Press, p. 98, ISBN 978-0-19-993921-3.

- ↑ "Bizaklik Thousand Buddha Caves". showcaves.com. Retrieved 2007-09-21.

- ↑ The Lost Murals of Bezeklik Thousand Buddha Caves

- ↑ Millward, James A. (2007). Eurasian Crossroads: A History of Xinjiang (illustrated ed.). Columbia University Press. p. 43. ISBN 0231139241. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- ↑ Modern Chinese Religion I (2 vol.set): Song-Liao-Jin-Yuan (960-1368 AD). BRILL. 8 December 2014. pp. 895–. ISBN 978-90-04-27164-7.

- ↑ Peter B. Golden (2011), Central Asia in World History, Oxford: Oxford University Press, p. 47, ISBN 978-0-19-515947-9.

- ↑ Sims, Eleanor, Boris I. Marshak, Ernst J. Grube, (2002), Peerless Images: Persian Painting and Its Sources, New Haven and London: Yale University Press, p. 154, ISBN 0-300-09038-2.

- ↑ von Le Coq, Albert. (1913). Chotscho: Facsimile-Wiedergaben der Wichtigeren Funde der Ersten Königlich Preussischen Expedition nach Turfan in Ost-Turkistan. Berlin: Dietrich Reimer (Ernst Vohsen), im Auftrage der Gernalverwaltung der Königlichen Museen aus Mitteln des Baessler-Institutes, p. 28. (Accessed 3 September 2016).

- ↑ James A. Millward (2007). Eurasian Crossroads: A History of Xinjiang. Columbia University Press. pp. 69–. ISBN 978-0-231-13924-3.

- ↑ Hamilton Alexander Rosskeen Gibb; Bernard Lewis; Johannes Hendrik Kramers; Charles Pellat; Joseph Schacht (1998). The Encyclopaedia of Islam. Brill. p. 677.

- ↑

- ↑ Michael Dillon (1 August 2014). Xinjiang and the Expansion of Chinese Communist Power: Kashgar in the Early Twentieth Century. Routledge. pp. 4–. ISBN 978-1-317-64721-8.

- ↑ Michael Dillon (1 August 2014). Xinjiang and the Expansion of Chinese Communist Power: Kashgar in the Early Twentieth Century. Routledge. pp. 17–. ISBN 978-1-317-64721-8.

- 1 2 Whitfield, Susan (2010). "A place of safekeeping? The vicissitudes of the Bezeklik murals". In Agnew, Neville. Conservation of ancient sites on the Silk Road: proceedings of the second International Conference on the Conservation of Grotto Sites, Mogao Grottoes, Dunhuang, People's Republic of China (PDF). Getty Publications. pp. 95–106. ISBN 978-1-60606-013-1.

- ↑ Ryukoku University Digital Archives Research Center

Further reading

- Chotscho : vol.1

- Altbuddhistische Kultstätten in Chinesisch-Turkistan : vol.1

- Polichetti, Massimiliano A.. 1999. “A Short Consideration Regarding Christian Elements in a Ninth Century Buddhist Wall-fainting from Bezeklik”. The Tibet Journal 24 (2). Library of Tibetan Works and Archives: 101–7. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43302426.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bezeklik caves. |

- Chotscho: Facsimile Reproduction of Important Findings of the First Royal Prussian Expedition to Turfan in East Turkistan, Berlin, 1913. A catalogue of the findings of the Second German Turfan Expedition (1904–1905) led by Le Coq, containing colour reproductions of the murals. (National Institute of Informatics – Digital Silk Road Project Digital Archive of Toyo Bunko Rare Books)

- Reconstruction of Bezeklik murals at Ryukoku Museum

- [ Bezeklik mural at Hermitage Museum]

- Silk Route photos

- Mogao Caves

- Silk Road site