Bernard-René de Launay

Bernard René Jourdan, marquis de Launay (1740–1789) was the French governor of the Bastille, the son of a previous governor, and commander of its garrison when it was stormed on 14 July 1789 (see Storming of the Bastille).

Early life

The marquis Bernard-René Jordan de Launay was born on the night of 8/9 April 1740 in the Bastille where his father was governor. At the age of eight he was appointed to an honorary position in the King's Musketeers (mousquetaires du roi). He subsequently entered the French Guards (gardes-françaises), a regiment permanently stationed in Paris except in time of war.

In 1776 de Launay succeeded M. de Jumilhac as Governor of the Bastille. As was the custom with many senior positions under the Ancien Régime, the marquis purchased the office of governor from his predecessor as a form of investment. The thirteen years that he spent in this position were uneventful, though on 19 December 1778 he reportedly made the mistake of failing to fire the cannon of the Bastille as a salute on the birth of a daughter (Madame Royale) to King Louis XVI. In August 1785 he was given responsibility for the imprisonment of two prime figures in the royal necklace scandal: Cardinal Louis de Rohan and Jeanne de La Motte-Valois. He behaved correctly and considerately with both, although the latter was an extremely difficult inmate.[1]

Until 1777 he was Seigneur of Bretonnière in Normandy. De Launay also owned and rented out a number of houses in the rue Saint-Antoine, neighboring the Bastille.

Role on 14 July 1789

The permanent garrison of the Bastille, under de Launay, consisted of about 80 invalides (veteran military pensioners) no longer considered suitable for regular army service. Two days before 14 July they were reinforced by thirty Swiss grenadiers from the Salis-Samade Regiment. Unlike Sombreuil, the governor of Hôtel des Invalides, who had accepted the revolutionaries' demands earlier that day, de Launay refused to surrender the prison fortress and hand over the arms and the gunpowder stored in the cellars.[2] He promised that he would not fire unless attacked and tried to negotiate with two delegates from the Hôtel de Ville, but the discussions drew out. A part of the impatient crowd started to enter the outer courtyard of the fortress after a small group broke the chains securing the drawbridge.[3] After shouting warnings the garrison opened fire.[2][3][4][5][6][7] The besiegers interpreted this as treachery on the part of de Launay.[4][5][6][7] The ensuing fighting lasted about four hours, resulting in about 100 casualties among the exposed crowd but only one death and three wounded[8] amongst the well-protected defenders firing from loopholes and battlements. With no source of water and only limited food supplies within the Bastille, de Launay decided to capitulate on the condition that nobody from within the fortress would be harmed.[9] In a note passed out through an opening in the drawbridge he threatened that he would blow up the entire fortress and the surrounding district if these conditions were rejected.[10] De Launay's conditions were rejected but he nevertheless capitulated, reportedly after members of the garrison prevented him from entering the cellars where the gunpowder was stored. At about 5pm firing from the fortress ceased and the drawbridge was suddenly lowered.[11]

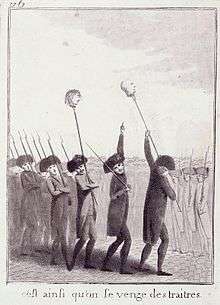

De Launay was then seized and his sword and baton of rank torn from him. He was supposed have been taken to the Hôtel de Ville by one of the leaders of the insurrection, soldier (future general) Pierre-Augustin Hulin, but on the way there, the furious crowd assaulted him, beat him and eventually lynched him by stabbing him repeatedly with their knives, swords and bayonets and shooting him once. The actual killing was reported to have taken place near the Hôtel de Ville when the struggling de Launay, desperate and abused, cried out "enough let me die" and kicked an unemployed cook named Desnot in the groin. After the killing, his head was sawn off by Mathieu Jouve Jourdan, a butcher. It was fixed on a pike to be carried through the streets. Three officers of the Bastille's garrison and two of their soldiers were also lynched, but the majority of the defenders were escorted through the mob by French Guards who had joined the attackers, and eventually released.[6]

Character

The history writer Simon Schama describes de Launay as a "reasonably conscientious if somewhat dour"[12] functionary who treated prisoners more humanely than his predecessors had done. The Marquis de Sade who had been transferred from the Bastille to another prison shortly before 14 July, commented that de Launay was "a so-called marquis whose grandfather was a servant".[13]

The officer commanding the Swiss detachment sent to reinforce de Launay, Lieutenant Deflue, subsequently accused his late superior of military incompetence, inexperience, irresoluteness and outright cowardice, which he had allegedly displayed before the siege.[14] Deflue's report, which was copied into the log book of his regiment and has survived, may not be fair to de Launay, who was put in an impossible position by the failure of the senior officers commanding the Royal troops concentrated in and around Paris to provide him with effective support. The Marshal de Broglie, who as Minister of War was in overall charge of the abortive efforts to suppress the disturbances of 1789, had however written on 5 July that "there are two sources of anxiety concerning the Bastille; the person of the commandant (de Launay) and the nature of the garrison there".[15]

De Launay had three daughters by two wives. Some of de Launay's brother's descendants settled in Russia (see Boris Delaunay and Vadim Delaunay for details). His killing is described graphically in Charles Dickens' A Tale of Two Cities (Book II, Chapter 21) and also in Hilary Mantel's A Place of Greater Safety.

References

- ↑ Jonathn Beckman, pages 159 & 205, "How to Ruin a Queen", ISBN 978-1848549982

- 1 2 Hampson, Norman, 1963. A social history of the French Revolution. P.74-75

- 1 2 Paris and the Politics of Revolution. At Liberty, Equality, Fraternity: Exploring the French Revolution, by Lynn Hunt and Jack Censer

- 1 2 George Rudé, Harvey J. Kaye. 2000. Revolutionary Europe, 1783-1815. P.73

- 1 2 Philip G. Dwyer, Peter McPhee. 2002. The French Revolution and Napoleon. P.18

- 1 2 3 GEO EPOCHE Nr. 22 - 05/06 - Französische Revolution

- 1 2 François Furet, Mona Ozouf, Arthur Goldhammer. 1989. A Critical Dictionary of the French Revolution. P. 125

- ↑ Simon Schama, page 404, "Citizens", ISBN 0-670-81012-6

- ↑ Simon Schama, page 403, "Citizens", ISBN 0-670-81012-6

- ↑ Hans-Jurgen Lusebrink, Rolf Reichardt, Nobert Schurer. 1997. The Bastille: A History of a Symbol of Despotism and Freedom, P.43

- ↑ Simon Schama, page 403, "Citizens", ISBN 0-670-81012-6

- ↑ Simon Schama, page 399, "Citizens", ISBN 0-670-81012-6

- ↑ Simon Schama, page 399, "Citizens", ISBN 0-670-81012-6

- ↑ Quétel, Claude, 1989. La Bastille: Histoire Vraie D'une Prison Legendaire, p. 353

- ↑ Munro Price, page 89, "The Fall of the French Monarchy", ISBN 0-330-48827-9