Benzodiazepine overdose

| Benzodiazepine overdose | |

|---|---|

| Classification and external resources | |

| Specialty | emergency medicine |

| ICD-10 | F13.0, T42.4 |

| ICD-9-CM | 969.4 |

| eMedicine | article/813255 |

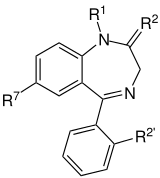

| Benzodiazepines |

|---|

The core structure of benzodiazepines. "R" labels denote common locations of side chains, which give different benzodiazepines their unique properties. |

Benzodiazepine overdose describes the ingestion of one of the drugs in the benzodiazepine class in quantities greater than are recommended or generally practiced. Death as a result of taking an excessive dose of benzodiazepines alone is uncommon (versus combined drug intoxication) but does occasionally happen.[1] Deaths after hospital admission are considered to be low.[2] However, combinations of high doses of benzodiazepines with alcohol, barbiturates, opioids or tricyclic antidepressants are particularly dangerous, and may lead to severe complications such as coma or death. The most common symptoms of overdose include central nervous system (CNS) depression and intoxication with impaired balance, ataxia, and slurred speech. Severe symptoms include coma and respiratory depression. Supportive care is the mainstay of treatment of benzodiazepine overdose. There is an antidote, flumazenil, but its use is controversial.[3]

As benzodiazepines are one of the most highly prescribed classes of drugs[4] they are commonly used in self-poisoning by drug overdose.[5][6] The various benzodiazepines differ in their toxicity since they produce varying levels of sedation in overdose. A 1993 British study of deaths during the 1980s found flurazepam and temazepam more frequently involved in drug-related deaths, causing more deaths per million prescriptions than other benzodiazepines. Flurazepam, now rarely prescribed in the United Kingdom and Australia, had the highest fatal toxicity index of any benzodiazepine (15.0), followed by temazepam (11.9), versus benzodiazepines overall (5.9), taken with or without alcohol.[7] An Australian (1995) study found oxazepam less toxic and less sedative, and temazepam more toxic and more sedative, than most benzodiazepines in overdose.[8] An Australian study (2004) of overdose admissions between 1987 and 2002 found alprazolam, which happens to be the most prescribed benzodiazepine in the U.S. by a large margin, to be more toxic than diazepam and other benzodiazepines. They also cited a review of the Annual Reports of the American Association of Poison Control Centers National Data Collection System, which showed alprazolam was involved in 34 fatal deliberate self-poisonings over 10 years (1992–2001), compared with 30 fatal deliberate self-poisonings involving diazepam.[9] In a New Zealand study (2003) of 200 deaths, Zopiclone, a benzodiazepine receptor agonist, had similar overdose potential as benzodiazepines.[10]

Signs and symptoms

Following an acute overdose of a benzodiazepine the onset of symptoms is typically rapid with most developing symptoms within 4 hours.[11] Patients initially present with mild to moderate impairment of central nervous system function. Initial signs and symptoms include intoxication, somnolence, diplopia, impaired balance, impaired motor function, anterograde amnesia, ataxia, and slurred speech. Most patients with pure benzodiazepine overdose will usually only exhibit these mild CNS symptoms.[11][12] Paradoxical reactions such as anxiety, delirium, combativeness, hallucinations, and aggression can also occur following benzodiazepine overdose.[13] Gastrointestinal symptoms such as nausea and vomiting have also been occasionally reported.[12]

Cases of severe overdose have been reported and symptoms displayed may include prolonged deep coma or deep cyclic coma, apnea, respiratory depression, hypoxemia, hypothermia, hypotension, bradycardia, cardiac arrest, and pulmonary aspiration, with the possibility of death.[11][14][15][16][17][18] Severe consequences are rare following overdose of benzodiazepines alone but the severity of overdose is increased significantly if benzodiazepines are taken in overdose in combination with other medications.[18] Significant toxicity may result following recreation drug misuse in conjunction with other CNS depressants such as opioids or ethanol.[19][20][21][22] The duration of symptoms following overdose is usually between 12 and 36 hours in the majority of cases.[12] The majority of drug-related deaths involve misuse of heroin or other opioids in combination with benzodiazepines or other CNS depressant drugs. In most cases of fatal overdose it is likely that lack of opioid tolerance combined with the depressant effects of benzodiazepines is the cause of death.[23]

The symptoms of an overdose such as sleepiness, agitation and ataxia occur much more frequently and severely in children. Hypotonia may also occur in severe cases.[24]

Toxicity

Benzodiazepines have a wide therapeutic index and taken alone in overdose rarely cause severe complications or fatalities.[12][25] More often than not, a patient who inadvertently takes more than the prescribed dose will simply feel drowsy and fall asleep for a few hours. Benzodiazepines taken in overdose in combination with alcohol, barbiturates, opioids, tricyclic antidepressants, or sedating antipsychotics, anticonvulsants, or antihistamines are particularly dangerous.[26] In the case of alcohol and barbiturates, not only do they have an additive effect but they also increase the binding affinity of benzodiazepines to the benzodiazepine binding site, which results in a very significant potentiation of the CNS and respiratory depressant effects.[27][28][29][30][31] In addition, the elderly and those with chronic illnesses are much more vulnerable to lethal overdose with benzodiazepines. Fatal overdoses can occur at relatively low doses in these individuals.[12][32][33][34]

Pathophysiology

Benzodiazepines bind to a specific benzodiazepine receptor, thereby enhancing the effect of the neurotransmitter gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) and causing CNS depression. In overdose situations this pharmacological effect is extended leading to a more severe CNS depression and potentially coma [12] or cardiac arrest.[35] Benzodiazepine-overdose-related coma may be characterised by an alpha pattern with the central somatosensory conduction time (CCT) after median nerve stimulation being prolonged and the N20 to be dispersed. Brain-stem auditory evoked potentials demonstrate delayed interpeak latencies (IPLs) I-III, III-V and I-V. Toxic overdoses of benzodiazepines therefore cause prolonged CCT and IPLs.[36][37][38]

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of benzodiazepine overdose may be difficult, but is usually made based on the clinical presentation of the patient along with a history of overdose.[12][39] Obtaining a laboratory test for benzodiazepine blood concentrations can be useful in patients presenting with CNS depression or coma of unknown origin. Techniques available to measure blood concentrations include thin layer chromatography, gas liquid chromatography with or without a mass spectrometer, and radioimmunoassay.[12] Blood benzodiazepine concentrations, however, do not appear to be related to any toxicological effect or predictive of clinical outcome. Blood concentrations are, therefore, used mainly to confirm the diagnosis rather than being useful for the clinical management of the patient.[12][40]

Treatment

Medical observation and supportive care are the mainstay of treatment of benzodiazepine overdose.[41] Although benzodiazepines are absorbed by activated charcoal,[42] gastric decontamination with activated charcoal is not beneficial in pure benzodiazepine overdose as the risk of adverse effects would outweigh any potential benefit from the procedure. It is recommended only if benzodiazepines have been taken in combination with other drugs that may benefit from decontamination.[43] Gastric lavage (stomach pumping) or whole bowel irrigation are also not recommended.[43] Enhancing elimination of the drug with hemodialysis, hemoperfusion, or forced diuresis is unlikely to be beneficial as these procedures have little effect on the clearance of benzodiazepines due to their large volume of distribution and lipid solubility.[43]

Supportive measures

Supportive measures include observation of vital signs, especially Glasgow Coma Scale and airway patency. IV access with fluid administration and maintenance of the airway with intubation and artificial ventilation may be required if respiratory depression or pulmonary aspiration occurs.[43] Supportive measures should be put in place prior to administration of any benzodiazepine antagonist in order to protect the patient from both the withdrawal effects and possible complications arising from the benzodiazepine. A determination of possible deliberate overdose should be considered with appropriate scrutiny, and precautions taken to prevent any attempt by the patient to commit further bodily harm.[8][44] Hypotension is corrected with fluid replacement, although catecholamines such as norepinephrine or dopamine may be required to increase blood pressure.[12] Bradycardia is treated with atropine or an infusion of norepinephrine to increase coronary blood flow and heart rate.[12]

Flumazenil

Flumazenil (Romazicon) is a competitive benzodiazepine receptor antagonist that can be used as an antidote for benzodiazepine overdose. Its use, however, is controversial as it has numerous contraindications.[3][45] It is contraindicated in patients who are on long-term benzodiazepines, those who have ingested a substance that lowers the seizure threshold, or in patients who have tachycardia, widened QRS complex on ECG, anticholinergic signs, or a history of seizures.[46] Due to these contraindications and the possibility of it causing severe adverse effects including seizures, adverse cardiac effects, and death,[47][48] in the majority of cases there is no indication for the use of flumazenil in the management of benzodiazepine overdose as the risks in general outweigh any potential benefit of administration.[3][43] It also has no role in the management of unknown overdoses.[5][45] In addition, if full airway protection has been achieved, a good outcome is expected, and therefore flumazenil administration is unlikely to be required.[49]

Flumazenil is very effective at reversing the CNS depression associated with benzodiazepines but is less effective at reversing respiratory depression.[45] One study found that only 10% of the patient population presenting with a benzodiazepine overdose are suitable candidates for flumazenil.[45] In this select population who are naive to and overdose solely on a benzodiazepine, it can be considered.[50] Due to its short half life, the duration of action of flumazenil is usually less than 1 hour, and multiple doses may be needed.[45] When flumazenil is indicated the risks can be reduced or avoided by slow dose titration of flumazenil.[44] Due to risks and its many contraindications, flumazenil should be administered only after discussion with a medical toxicologist.[50][51]

Epidemiology

In a Swedish (2003) study benzodiazepines were implicated in 39% of suicides by drug poisoning in the elderly 1992-1996. Nitrazepam and flunitrazepam accounted for 90% of benzodiazepine implicated suicides. In cases where benzodiazepines contributed to death, but were not the sole cause, drowning, typically in the bath, was a common method used. Benzodiazepines were the predominant drug class in suicides in this review of Swedish death certificates. In 72% of the cases, benzodiazepines were the only drug consumed. Thus, many of deaths associated with benzodiazepine overdoses may not be a direct result of the toxic effects but either due to being combined with other drugs or used as a tool to complete suicide using a different method, e.g. drowning.[52]

In a Swedish retrospective study of deaths of 1987, in 159 of 1587 autopsy cases benzodiazepines were found. In 44 of these cases the cause of death was natural causes or unclear. The remaining 115 deaths were due to accidents (N = 16), suicide (N = 60), drug addiction (N = 29) or alcoholism (N = 10). In a comparison of suicides and natural deaths, the concentrations both of flunitrazepam and nitrazepam (sleeping medications) were significantly higher among the suicides. In four cases benzodiazepines were the sole cause of death.[53]

In Australia, a study of 16 deaths associated with toxic concentrations of benzodiazepines during the period of 5 years leading up to July 1994 found preexisting natural disease as a feature of 11 cases; 14 cases were suicides. Cases where other drugs, including ethanol, had contributed to the death were excluded. In the remaining five cases, death was caused solely by benzodiazepines. Nitrazepam and temazepam were the most prevalent drugs detected, followed by oxazepam and flunitrazepam.[54] A review of self poisonings of 12 months 1976 - 1977 in Auckland, New Zealand, found benzodiazepines implicated in 40% of the cases.[55] A 1993 British study found flurazepam and temazepam to have the highest number of deaths per million prescriptions among medications commonly prescribed in the 1980s. Flurazepam, now rarely prescribed in the United Kingdom and Australia, had the highest fatal toxicity index of any benzodiazepine (15.0) followed by Temazepam (11.9), versus 5.9 for benzodiazepines overall, taken with or without alcohol.[7]

References

- ↑ Dart, Richard C. (1 December 2003). Medical Toxicology (3rd ed.). USA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 811. ISBN 978-0-7817-2845-4.

- ↑ Höjer J, Baehrendtz S, Gustafsson L (August 1989). "Benzodiazepine poisoning: experience of 702 admissions to an intensive care unit during a 14-year period". J. Intern. Med. 226 (2): 117–22. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2796.1989.tb01365.x. PMID 2769176.

- 1 2 3 Seger DL (2004). "Flumazenil--treatment or toxin". J. Toxicol. Clin. Toxicol. 42 (2): 209–16. doi:10.1081/CLT-120030946. PMID 15214628.

- ↑ Taylor S, McCracken CF, Wilson KC, Copeland JR (November 1998). "Extent and appropriateness of benzodiazepine use. Results from an elderly urban community". Br J Psychiatry. 173 (5): 433–8. doi:10.1192/bjp.173.5.433. PMID 9926062.

- 1 2 Ngo AS, Anthony CR, Samuel M, Wong E, Ponampalam R (July 2007). "Should a benzodiazepine antagonist be used in unconscious patients presenting to the emergency department?". Resuscitation. 74 (1): 27–37. doi:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2006.11.010. PMID 17306436.

- ↑ Jonasson B, Jonasson U, Saldeen T (January 2000). "Among fatal poisonings dextropropoxyphene predominates in younger people, antidepressants in the middle aged and sedatives in the elderly". J. Forensic Sci. 45 (1): 7–10. PMID 10641912.

- 1 2 Serfaty M, Masterton G (January 1994). "Fatal poisonings attributed to benzodiazepines in Britain during the 1980s". British Journal of Psychiatry. 163 (3): 386–93. doi:10.1192/bjp.163.3.386. PMID 8104653.

- 1 2 Buckley NA, Dawson AH, Whyte IM, O'Connell DL (28 January 1995). "Relative toxicity of benzodiazepines in overdose". BMJ. 310 (6974): 219–21. doi:10.1136/bmj.310.6974.219. PMC 2548618

. PMID 7866122.

. PMID 7866122. - ↑ Isbister GK, O'Regan L, Sibbritt D, Whyte IM (July 2004). "Alprazolam is relatively more toxic than other benzodiazepines in overdose". Br J Clin Pharmacol. 58 (1): 88–95. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.2004.02089.x. PMC 1884537

. PMID 15206998.

. PMID 15206998. - ↑ Reith DM, Fountain J, McDowell R, Tilyard M (2003). "Comparison of the fatal toxicity index of zopiclone with benzodiazepines". J. Toxicol. Clin. Toxicol. 41 (7): 975–80. doi:10.1081/CLT-120026520. PMID 14705844.

- 1 2 3 Wiley CC, Wiley JF (1998). "Pediatric benzodiazepine ingestion resulting in hospitalization". J. Toxicol. Clin. Toxicol. 36 (3): 227–31. doi:10.3109/15563659809028944. PMID 9656979.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Gaudreault P, Guay J, Thivierge RL, Verdy I (1991). "Benzodiazepine poisoning. Clinical and pharmacological considerations and treatment". Drug Saf. 6 (4): 247–65. doi:10.2165/00002018-199106040-00003. PMID 1888441.

- ↑ Garnier R, Medernach C, Harbach S, Fournier E (April 1984). "[Agitation and hallucinations during acute lorazepam poisoning in children. Apropos of 65 personal cases]". Ann Pediatr (Paris) (in French). 31 (4): 286–9. PMID 6742700.

- ↑ Berger R, Green G, Melnick A (September 1975). "Cardiac arrest caused by oral diazepam intoxication". Clin Pediatr (Phila). 14 (9): 842–4. doi:10.1177/000992287501400910. PMID 1157438.

- ↑ Welch TR, Rumack BH, Hammond K (1977). "Clonazepam overdose resulting in cyclic coma". Clin. Toxicol. 10 (4): 433–6. doi:10.3109/15563657709046280. PMID 862377.

- ↑ Höjer J, Baehrendtz S, Gustafsson L (August 1989). "Benzodiazepine poisoning: experience of 702 admissions to an intensive care unit during a 14-year period". J. Intern. Med. 226 (2): 117–22. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2796.1989.tb01365.x. PMID 2769176.

- ↑ Busto U, Kaplan HL, Sellers EM (February 1980). "Benzodiazepine-associated emergencies in Toronto". Am J Psychiatry. 137 (2): 224–7. PMID 6101526.

- 1 2 Greenblatt DJ, Allen MD, Noel BJ, Shader RI (April 1977). "Acute overdosage with benzodiazepine derivatives". Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 21 (4): 497–514. PMID 14802.

- ↑ Lai SH; Yao YJ; Lo DS (October 2006). "A survey of buprenorphine related deaths in Singapore". Forensic Sci Int. 162 (1–3): 80–6. doi:10.1016/j.forsciint.2006.03.037. PMID 16879940.

- ↑ Koski A, Ojanperä I, Vuori E (May 2003). "Interaction of alcohol and drugs in fatal poisonings". Hum Exp Toxicol. 22 (5): 281–7. doi:10.1191/0960327103ht324oa. PMID 12774892.

- ↑ Wishart, David (2006). "Triazolam". DrugBank. Retrieved 2006-03-23.

- ↑ Hung DZ, Tsai WJ, Deng JF (July 1992). "Anterograde amnesia in triazolam overdose despite flumazenil treatment: a case report". Hum Exp Toxicol. 11 (4): 289–90. doi:10.1177/096032719201100410. PMID 1354979.

- ↑ National Treatment Agency for Substance Misuse (2007). "Drug misuse and dependence - UK guidelines on clinical management" (PDF). United Kingdom: Department of Health.

- ↑ Pulce C, Mollon P, Pham E, Frantz P, Descotes J (April 1992). "Acute poisonings with ethyle loflazepate, flunitrazepam, prazepam and triazolam in children". Vet Hum Toxicol. 34 (2): 141–3. PMID 1354907.

- ↑ Wolf BC, Lavezzi WA, Sullivan LM, Middleberg RA, Flannagan LM (2005). "Alprazolam-related deaths in Palm Beach County". Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 26 (1): 24–7. doi:10.1097/01.paf.0000153994.95642.c1. PMID 15725773.

- ↑ Charlson F, Degenhardt L, McLaren J, Hall W, Lynskey M (February 2009). "A systematic review of research examining benzodiazepine-related mortality". Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 18 (2): 93–103. doi:10.1002/pds.1694. PMID 19125401.

- ↑ Dietze P, Jolley D, Fry C, Bammer G (May 2005). "Transient changes in behaviour lead to heroin overdose: results from a case-crossover study of non-fatal overdose". Addiction. 100 (5): 636–42. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01051.x. PMID 15847621.

- ↑ Hammersley R; Cassidy MT; Oliver J (July 1995). "Drugs associated with drug-related deaths in Edinburgh and Glasgow, November 1990 to October 1992". Addiction. 90 (7): 959–65. doi:10.1046/j.1360-0443.1995.9079598.x. PMID 7663317.

- ↑ Ticku MK, Burch TP, Davis WC (1983). "The interactions of ethanol with the benzodiazepine-GABA receptor-ionophore complex". Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 18 Suppl 1: 15–8. doi:10.1016/0091-3057(83)90140-5. PMID 6138771.

- ↑ Kudo K, Imamura T, Jitsufuchi N, Zhang XX, Tokunaga H, Nagata T (April 1997). "Death attributed to the toxic interaction of triazolam, amitriptyline and other psychotropic drugs". Forensic Sci. Int. 86 (1–2): 35–41. doi:10.1016/S0379-0738(97)02110-5. PMID 9153780.

- ↑ Rogers, Wo; Hall, Ma; Brissie, Rm; Robinson, Ca (Jan 1997). "Detection of alprazolam in three cases of methadone/benzodiazepine overdose". Journal of forensic sciences. 42 (1): 155–6. ISSN 0022-1198. PMID 8988593.

- ↑ Sunter JP, Bal TS, Cowan WK (September 1988). "Three cases of fatal triazolam poisoning". BMJ. 297 (6650): 719. doi:10.1136/bmj.297.6650.719. PMC 1834083

. PMID 3147739.

. PMID 3147739. - ↑ Brødsgaard I; Hansen AC; Vesterby A (June 1995). "Two cases of lethal nitrazepam poisoning". Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 16 (2): 151–3. doi:10.1097/00000433-199506000-00015. PMID 7572872.

- ↑ Reidenberg MM, Levy M, Warner H, Coutinho CB, Schwartz MA, Yu G, Cheripko J (April 1978). "Relationship between diazepam dose, plasma level, age, and central nervous system depression". Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 23 (4): 371–4. PMID 630787.

- ↑ Berger, R,; Green G; Melnick A. (1975). "Cardiac Arrest Caused by Oral Diazepam Intoxication". Clinical Pediatrics. 14 (9): 842–844. doi:10.1177/000992287501400910. PMID 1157438.

- ↑ Rumpl E; Prugger M; Battista HJ; Badry F; Gerstenbrand F; Dienstl F (December 1988). "Short latency somatosensory evoked potentials and brain-stem auditory evoked potentials in coma due to CNS depressant drug poisoning. Preliminary observations". Electroencephalography and clinical neurophysiology. 70 (6): 482–9. doi:10.1016/0013-4694(88)90146-0. PMID 2461282.

- ↑ Pasinato E, Franciosi A, De Vanna M (Apr 1983). ""Alpha pattern coma" after poisoning with flunitrazepam and bromazepam. Case description". Minerva psichiatrica. 24 (2): 69–74. ISSN 0374-9320. PMID 6140613.

- ↑ Carroll WM, Mastiglia FL (December 1977). "Alpha and beta coma in drug intoxication" (PDF). Br Med J. 2 (6101): 1518–9. doi:10.1136/bmj.2.6101.1518-a. PMC 1632784

. PMID 589310.

. PMID 589310. - ↑ Perry HE, Shannon MW (June 1996). "Diagnosis and management of opioid- and benzodiazepine-induced comatose overdose in children". Current Opinion in Pediatrics. 8 (3): 243–7. doi:10.1097/00008480-199606000-00010. PMID 8814402.

- ↑ Jatlow P, Dobular K, Bailey D (October 1979). "Serum diazepam concentrations in overdose. Their significance". Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 72 (4): 571–7. PMID 40432.

- ↑ Welch TR, Rumack BH, Hammond K (1977). "Clonazepam overdose resulting in cyclic coma". Clin. Toxicol. 10 (4): 433–6. doi:10.3109/15563657709046280. PMID 862377.

- ↑ el-Khordagui LK, Saleh AM, KhalIl SA (1987). "Adsorption of benzodiazepines on charcoal and its correlation with in vitro and in vivo data". Pharm Acta Helv. 62 (1): 28–32. PMID 2882522.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Whyte, IM (2004). "Benzodiazepines". Medical toxicology. Philadelphia: Williams & Wilkins. pp. 811–22. ISBN 0-7817-2845-2.

- 1 2 Weinbroum AA, Flaishon R, Sorkine P, Szold O, Rudick V (September 1997). "A risk-benefit assessment of flumazenil in the management of benzodiazepine overdose". Drug Saf. 17 (3): 181–96. doi:10.2165/00002018-199717030-00004. PMID 9306053.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Nelson, LH; Flomenbaum N; Goldfrank LR; Hoffman RL; Howland MD; Neal AL (2006). "Antidotes in depth: Flumazenil". Goldfrank's toxicologic emergencies (8th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. pp. 1112–7. ISBN 0-07-147914-7.

- ↑ Spivey WH (1992). "Flumazenil and seizures: analysis of 43 cases". Clin Ther. 14 (2): 292–305. PMID 1611650.

- ↑ Marchant B, Wray R, Leach A, Nama M (September 1989). "Flumazenil causing convulsions and ventricular tachycardia". BMJ. 299 (6703): 860. doi:10.1136/bmj.299.6703.860-b. PMC 1837717

. PMID 2510872.

. PMID 2510872. - ↑ Burr W, Sandham P, Judd A (June 1989). "Death after flumazepil". BMJ. 298 (6689): 1713. doi:10.1136/bmj.298.6689.1713-a. PMC 1836759

. PMID 2569340.

. PMID 2569340. - ↑ Hoffman RS, Goldfrank LR (August 1995). "The poisoned patient with altered consciousness. Controversies in the use of a 'coma cocktail'". JAMA. 274 (7): 562–9. doi:10.1001/jama.274.7.562. PMID 7629986.

- 1 2 Nelson LH, Flomenbaum N, Goldfrank LR, Hoffman RL, Howland MD, Neal AL (2006). "Sedative-hypnotic agents". Goldfrank's toxicologic emergencies (8th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. pp. 929–51. ISBN 0-07-147914-7.

- ↑ Thomson JS, Donald C, Lewin K (February 2006). "Use of Flumazenil in benzodiazepine overdose". Emerg Med J. 23 (2): 162. PMC 2564056

. PMID 16439763.

. PMID 16439763. - ↑ Carlsten, A; Waern M; Holmgren P; Allebeck P (2003). "The role of benzodiazepines in elderly suicides". Scand J Public Health. 31 (3): 224–8. doi:10.1080/14034940210167966. PMID 12850977.

- ↑ Ericsson HR; Holmgren P; Jakobsson SW; Lafolie P; De Rees B (November 10, 1993). "Benzodiazepine findings in autopsy material. A study shows interacting factors in fatal cases". Läkartidningen. 90 (45): 3954–7. PMID 8231567.

- ↑ Drummer OH; Ranson DL (December 1996). "Sudden death and benzodiazepines". Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 17 (4): 336–42. doi:10.1097/00000433-199612000-00012. PMID 8947361.

- ↑ Large RG (September 1978). "Self-poisoning in Auckland reconsidered". N. Z. Med. J. 88 (620): 240–3. PMID 31581.