Beijing–Shanghai High-Speed Railway

| Beijing–Shanghai High-Speed Railway 京沪高速铁路 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Overview | |||

| Type | High-speed rail | ||

| Status | Operational | ||

| Locale | People's Republic of China | ||

| Termini |

Beijing South Tianjin West Shanghai Hongqiao | ||

| Stations | 24 | ||

| Ridership | 100 million per year (2014)[1] | ||

| Operation | |||

| Opened | June 30, 2011 | ||

| Owner | China Railways | ||

| Operator(s) | China Railway High-speed | ||

| Rolling stock | CRH380AL CRH380BL CRH380CL | ||

| Technical | |||

| Line length |

1,318 km (819 mi) 1,302 km (809 mi) (main line) | ||

| Track gauge | 1,435 mm (4 ft 8 1⁄2 in) | ||

| Minimum radius |

mostly 7,000 meters, or 400 meters near Beijing South | ||

| Operating speed | 350 km/h (217 mph) | ||

| Maximum incline | 2%[2] | ||

| |||

| Jinghu High-Speed Railway | |||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 京沪高速铁路 | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 京滬高速鐵路 | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Beijing-Shanghai High-Speed Railway | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Line length: | 1,318 km (819 mi) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Track gauge: | 1,435 mm (4 ft 8 1⁄2 in) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Maximum speed: | 350 km/h (217 mph) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Stations and structures[3] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Legend

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

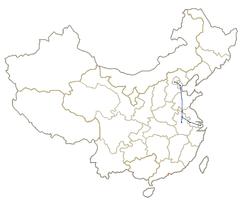

The Beijing–Shanghai High-Speed Railway (or Jinghu High-Speed Railway from its Chinese name) is a 1,318-kilometre (819 mi) long high-speed railway that connects two major economic zones in the People's Republic of China, the Bohai Economic Rim and the Yangtze River Delta.[4] Construction began on April 18, 2008,[5] and a ceremony to mark the completion of track laying was held on November 15, 2010.[6] The line opened to the public for commercial service on June 30, 2011.[7] This rail line is the world's longest high-speed line ever constructed in a single phase.[8][9][10]

Under former Minister of Railways Liu Zhijun, the railway line was the first one designed for a maximum speed of 380 km/h in commercial operations. The non-stop train from Beijing South to Shanghai Hongqiao was expected to finish the 1,305 kilometres (811 mi) journey in 3 hours and 58 minutes,[11] averaging 329 kilometres per hour (204 mph), making it the fastest scheduled train in the world, compared to 9 hours and 49 minutes on the fastest trains running on the parallel conventional railway.[12] However, following Liu Zhijun's dismissal in February 2011, several major changes were announced. First, trains would be slowed to a maximum speed of 300 km/h (186 mph), reducing operating costs. At this speed, the fastest trains would take 4 hours and 48 minutes to travel from Beijing South to Shanghai Hongqiao, making one stop at Nanjing South.[13] Additionally, a slower class of trains running at 250 km/h (155 mph) would be operated, making more stops and charging lower fares.

Specifications

The Beijing–Shanghai High-Speed Railway Co., Ltd. was in charge of construction. The project was expected to cost 220 billion yuan (about $32 billion). An estimated 220,000 passengers are expected to use the trains each day,[4] which is double the current capacity.[14] During peak hours, trains should run every five minutes.[14] 1,140 km, or 87% of the railway is elevated. There are 244 bridges along the line. The 164-km long Danyang–Kunshan Grand Bridge is the longest bridge in the world,[15] the 114-km long viaduct bridge between Langfang and Qingxian is the second longest in the world, and the viaduct between Beijing's 4th Ring Road and Langfang is the fifth longest. The line also includes 22 tunnels, totaling 16.1 km. 1,268 km of the length is ballastless.

According to Zhang Shuguang, then deputy chief designer of China's high-speed railway network, the designed continuous operating speed is 350 km/h (217 mph), with a maximum speed of up to 380 km/h (236 mph). The average commercial speed from Beijing to Shanghai was planned to be 330 km/h (205 mph), which would have cut the train travel time from 10 hours to 4 hours.[16] The rolling stock used on this line consists mainly of CRH380 trains. The CTCS-3 based train control system is used on the line, to allow for a maximum speed of 380 km/h of running and a minimum train interval of 3 minutes. With power consumption of 20 MW and capacity of about 1,050 passengers, the energy consumption per passenger from Beijing to Shanghai should be less than 80kWh.

History

China's two most important cities, Beijing and Shanghai, were not linked by rail until 1912, when the Jinpu railway was completed between Tianjin and Pukou. With the existing railway between Beijing and Tianjin, which was completed in 1900, the Huning railway between Nanjing and Shanghai opened in 1908, interrupted by a ferry between Pukou and Nanjing across the Yangtze River. A weekly Beijing–Shanghai direct train was first introduced in 1913.

In 1933 a train ride from Beijing to Shanghai took around 44 hours, at an average speed of 33 km/h. Passengers had to get off in Pukou with their luggage, board a ferry named "Kuaijie" across the Yangtze, and get on another connecting train in Xiaguan on the other side of the river.

In 1933 the Nanjing Train Ferry was opened for service. The new train ferry, "Changjiang" (Yangtze), built by a British company, was 113.3 meters long, 17.86 meters wide, was able to carry 21 freight cars or 12 passenger cars. Passengers could remain on the train when crossing the river, and the travel time was thus cut to around 36 hours. The train service was suspended during the Japanese invasion.

In 1949 from Shanghai's North railway station toward Beijing (then Beiping) it took 36 hours, 50 minutes, at an average speed of 40 km/h. In 1956 the trip time was cut to 28 hours, 17 minutes. In the early 1960s the travel time was further cut to 23 hours, 39 minutes.

In October 1968, the Nanjing Yangtze River Bridge was opened. The travel time was cut to 21 hours, 34 minutes. As new diesel locomotives were introduced in the 1970s, the speed was increased further. In 1986, the travel time was 16 hours, 59 minutes.

China introduced six line schedule reductions from 1997 to 2007. In October 2001, train T13/T14 took about 14 hours from Beijing to Shanghai. On April 18, 2004, Z-series trains were introduced. The trip time was cut to 11 hours, 58 minutes. There were five trains departing around 7 pm every day, each 7 minutes apart, arriving at their destination the next morning.

The railway was completely electrified in 2006. On April 18, 2007, the new CRH bullet train was introduced on the upgraded railway. A day-time train D31 served the route, departing from Beijing at 10:50 every morning, and arriving at Shanghai at 20:49 in the evening, travelling mostly at 160–200 km/h (up to 250 km/h in a very short section between Anting and Shanghai West). In 2008 overnight sleeper CRH trains were introduced, replacing the locomotive-hauled Z sleeper trains. With a new high-speed intercity line opening between Nanjing and Shanghai in the summer of 2010, the sleeper trains made use of the high-speed line in the Shanghai–Nanjing section, travelling at 250 km/h for a longer distance. The fastest sleeper trains took 9 hours, 49 minutes, with four intermediate stops, at an average speed of 149 km/h.

As the Nanjing Yangtze Bridge connected the two sections of the railway into a continuous line, the entire railway between Beijing and Shanghai was renamed the Jinghu Railway, with Jing (京) being the standard Chinese abbreviation for Beijing, and Hu (沪), short for Shanghai. The Jinghu Railway has served as China's busiest railway for nearly a century. Due to rapid growth in passenger and freight traffic in the last 20 years, this line has reached and surpassed capacity.

Dedicated high-speed rail proposal

The Jinghu High-Speed Railway was proposed in the early 1990s, because one quarter of the country’s population lived along the existing Beijing-Shanghai rail line[14] In December 1990, the Ministry of Railways submitted to the National People's Congress a proposal to build the Beijing–Shanghai high speed railway parallel to the existing Beijing–Shanghai railway line.[17] In 1995, Premier Li Peng announced that work on the Beijing–Shanghai High-Speed Railway would begin in the 9th Five Year Plan (1996–2000). The Ministry's initial design for the high-speed rail line was completed, and a report was submitted for state approval in June 1998.[18] The construction plan was set in 2004, after a five-year debate on whether to use steel-on-steel rail track, or maglev technology.[19][20]

Technology debate

Although engineers originally said construction could take until 2015, the China’s Ministry of Railways initially promised a 2010 opening date for the new line.[4] However, the Ministry did not anticipate an ensuing debate over the possible use of maglev technology.[21] Although more traditional steel-on-steel rail technology was chosen for the railway, the technology debate resulted in a substantial delay of the railway's feasibility studies, completed in March 2006. The current rolling stock is the CRH380AL, which is a Chinese electric high-speed train that was developed by China South Locomotive & Rolling Stock Corporation Limited (CSR). CRH380A is one of the four Chinese train series which have been designed for the new standard operating speed of 380 km/h (236 mph) on newly constructed Chinese high-speed main lines. The other three are CRH380B, CRH380C and CRH380D.

Engineering challenges

Testing began shortly thereafter on the main line section between Shanghai and Nanjing. This section of the line sits on the soft soil of the Yangtze Delta, providing engineers an example of the more difficult challenges they would face in later construction. In addition to these challenges, high speed trains use extensive amounts of aluminium alloy, with specially designed windscreen glass capable of withstanding avian impacts.

Construction

Construction work began on April 18, 2008. Track-laying was started on July 19, 2010, and completed on November 15, 2010.[6] The overhead catenary work was completed on February 4, 2011. According to CCTV, more than 130,000 construction workers and engineers were at work at the peak of the construction phase.

According to the Ministry of Railways, construction has used twice as much concrete as the Three Gorges dam, and 120 times the amount of steel in the Beijing National Stadium. There are 244 bridges and 22 tunnels built to standardised designs, and the route is monitored by 321 seismic, 167 windspeed and 50 rainfall sensors.[22]

Finances

In 2006, it was estimated that the line would cost between CN¥130 billion (US$16.25 billion) and ¥170 billion ($21.25 billion).[23] The following year, the estimated cost had revised to ¥200 billion ($25 billion), or ¥150 million per kilometer.[24][25] Due to rapid rises in the costs of labour, construction materials and land acquisitions over the previous years, by July 2008, the estimated cost was increased to ¥220 billion ($32 billion). By then, the state-owned company Beijing–Shanghai High-Speed Railway, established to raise funds for the project, had raised ¥110 billion, with the remaining to be sourced from local governments, share offerings, bank loans and, for the first time for a railway project, foreign investment.[26] In the end, investment in the project totalled ¥217.6 billion ($34.7 billion).[27]

Rolling stock

The 300 km/h services use CSR CRH380A and CNR CRH380B trainsets, while slower 250 km/h services are operated using CSR CRH2 trainsets.[22] First and Second Class coaches are available on all trains. On the shorter trains, a six-person Premier Class compartment is available. Available on the longer trains are up to 28 Business Class seats and a full-length dining car.

On December 3, 2010, a 16-car CRH380AL trainset set a speed record of 486.1 km/h (302.0 mph) on the Zaozhuang West to Bengbu section of the line during a test run. On January 10, 2011, another 16-car modified CRH380BL train set a speed record of 487.3 km/h (302.8 mph) during a test run.[28]

Operation

First day in service

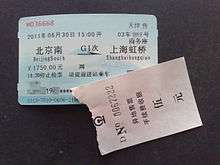

Tickets were put on sale at 09:00 on June 24, 2011, and sold out within an hour.[29] To compete with the new train service, airlines slashed the cost of flights between Beijing and Shanghai by up to 65%.[30] Economy air fares between Beijing and Shanghai fell by 52%.

After July 1, 2011

More than 90 trains a day run between Beijing South and Shanghai Hongqiao from 07:00 to until 18:00. Sleeper bullet trains on the upgraded railway were cancelled at the beginning,[31] but later resumed. The new line will increase the freight capacity of the old line by 50 million tons per year between Beijing and Shanghai.[31][32]

In its second week in service, the system experienced three malfunctions in four days.[33] On July 10, 2011, trains were delayed after heavy winds and a thunderstorm caused power supply problems in Shandong province.[33] On July 12, 2011, trains were delayed again when another power failure occurred in Suzhou. On July 13, 2011, a transformer malfunction in Changzhou forced a train to half its top speed, forcing passengers to take a backup train.[34] Within two weeks after opening, airline prices had rebounded due to frequent malfunctions on the line.[35] Airline ticket sales were only down 5% in July 2011 compared to June 2011, after the opening of the line.[36] A spokesman for the Ministry of Railways apologized for the glitches and delays, stating that in the two weeks since service had begun only 85.6% of trains had arrived on time.[37] The line's average daily ridership in its initial two weeks of operation was 165,000 passengers daily, while 80,000 passengers every day continued to ride on the slower and less expensive old railway.[37] The figure of 165,000 daily riders is three-quarters of the forecast of 220,000 daily riders[4] and is consistent with a pattern where new rail services build ridership over a period of time after opening (see TGV, Ridership). On August 12, 2011, after several delays caused by equipment problems, 54 CRH380BL trains running on this line were recalled by their manufacturer.[38] They returned to regular service on November 16, 2011.

By March 2013, the line had carried 100 million passengers.[27]

Fares

On June 13, 2011, the list of fares was announced at a Ministry of Railways press conference. The fares from Beijing South to Shanghai Hongqiao in RMB Yuan are listed below:[39]

| Speed | 2nd-class seat | 1st-class seat | VIP Seat (Sightseeing Seat) | Quickest Journey Time | Daily services |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G(300 km/h) | 555 | 935 | 1750 | 4h48m | 63 |

| D(250 km/h) | 410 | 650 | 1260* | 7h56m | 27 |

Note: *Only available on services using the CRH380AL or CRH380BL trains

On June 14, 2011, the list of stop-by-stop fares was published on the Ministry of Railways' website.[40]

With tickets priced at ¥1750 one way in the sightseeing compartment at the ends of the trains, passengers can sit behind the driver .[41] Tickets at the same price all feature seats which recline in full. Holders of these tickets are additionally given free lounge access at major stations, are served a free meal onboard close to meal times, and are given unlimited refills of non-alcoholic drinks while on board.

Online ticketing service

The online ticket service opened when brick and mortar ticket service started. Passengers can buy tickets on the internet and pay the fare by debit or credit card. If the passenger uses a 2nd-generation PRC ID Card and does not want any documents printed, they can use their ID card directly as the ticket to pass the AFC, otherwise the passenger must change to a paper ticket prior to travel. Since late 2011, it has also been possible for users of these ID cards to print a ticket with the remark "Ticket Checked" after the end of the trip for reimbursement purposes.

Components

| Section | Description | Designed speed (km/h) |

Length (km) |

Construction start date |

Open date |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beijing–Shanghai High-Speed Railway |

Main north-south HSR Corridor of East China | 350 | 1433 | 2008-01-08 | 2012-10-16 |

| Beijing–Shanghai Section (Beijing–Shanghai High-Speed Railway)  |

HSR from Beijing to Shanghai via Tianjin, Jinan, Xuzhou, Bengbu and Nanjing | 350 | 1302 | 2008-04-18 | 2011-06-30[42] |

| Hefei–Bengbu Section (Hefei–Bengbu High-Speed Railway) |

Spur off Jinghu HSR from Bengbu to Hefei | 350 | 131 | 2008-01-08 | 2012-10-16[43] |

Stations & Service

There are 24 stations on the line.[3][44] The line has two speeds of service, 300 km/h (186 mph) 'G' trains and 250 km/h (155 mph) 'D' trains. The fastest 300 km/h 'G' trains make only one stop, in Nanjing South, and take 4 hours 48 minutes to make the full trip. However, the majority of 300 km/h 'G' trains make six or seven intermediate stops and take between 5 hours 20 minutes up to 5 hours 30 minutes to make the full trip, with different trains making different intermediate stops.[45] Almost all 300 km/h trains stop at Jinan and Nanjing. The 250 km/h 'D' trains make more intermediate stops and take between 7 hours 52 minutes up to 9 hours to complete the full journey from Beijing to Shanghai. Currently the G services from Beijing to Nanjing are the fastest in the world doing the journey at an average speed of over 279 km/h (173 mph).

Note: * - Lines in italic text are under construction or planned

Bridges

The railway line has some of the longest bridges in the world. They include:

- Danyang–Kunshan Grand Bridge - longest bridge in the world.[47]

- Tianjin Grand Bridge - second longest bridge in the world.[47]

- Beijing Grand Bridge

- Cangzhou–Dezhou Grand Bridge

- Nanjing Qinhuai River Bridge

- Zhenjiang Beijing–Hangzhou Canal Bridge

References

- ↑ Chang, Lyu (27 January 2015). "Beijing-Shanghai high-speed line turns profitable in 2014". China Daily. Retrieved 8 May 2015.

- ↑ http://www.railpage.com.au/f-p1178286.htm

- 1 2 铁运电 [2011] 70号:关于公布京沪高铁车站站名的通知

Transport Bureau of the Ministry of Railways, Telegram [2011] No. 70: Notice on the announcement of station names of Beijing–Shanghai High-Speed Railway - 1 2 3 4 Beijing-Shanghai High-Speed Line, China. Railway-Technology.com, 2008-09-25.

- ↑ "China starts work on Beijing-Shanghai express railway". China View. 2008-04-17. Archived from the original on 22 April 2008. Retrieved 2008-04-19.

- 1 2 "Tracklaying complete on Beijing - Shanghai high speed line". Railway Gazette International. 15 November 2010. Retrieved 2010-11-17.

- ↑ "Beijing-Shanghai high-speed train makes debut". Retrieved 2011-06-30.

- ↑ "Beijing-Shanghai high-speed train makes debut". The Independent. 30 June 2011. Retrieved 30 June 2011.

- ↑ "Beijing to Shanghai Railway: diary of a 4h 48m journey". Daily Telegraph. 30 June 2011. Retrieved 30 June 2011.

- ↑ "High-Speed Train Links Beijing, Shanghai". Wall Street Journal. 30 June 2011. Retrieved 30 June 2011.

- ↑ (Chinese) 【来源:第一时间】 (责任编辑:张纯洁). "京沪高铁19日起铺轨 全程不到四小时-新闻频道-和讯网". News.hexun.com. Archived from the original on 23 July 2011. Retrieved 2011-06-30.

- ↑ (Chinese) "京沪京杭动车下月开行卧铺". Thebeijingnews.com. 2008-11-25. Retrieved 2011-06-30.

- ↑ (Chinese) "京沪高铁列车开始试跑 最快4小时48分跑完全程_财经频道_凤凰网". Finance.ifeng.com. Archived from the original on 20 July 2011. Retrieved 2011-06-30.

- 1 2 3 Construction of Beijing to Shanghai High-speed Railway Kicks Off. CRIEnglish.com, January 2008. (accessed: 2008-09-25)

- ↑ (Chinese) "京沪高铁江苏江苏段90%是桥梁 堪称"桥上铁"_时政频道_新华网". News.xinhuanet.com. Retrieved 2011-06-30.

- ↑ (Chinese) Zhang, Shuguang (February 2009). 京沪高速铁路系统优化研究 [Beijing-Shanghai High-Speed Railway System Optimization Research] (in Chinese). China Railway Press. p. 10. ISBN 978-7-113-09517-8.

- ↑ (Chinese) "京沪高速铁路的论证历程大事记" Accessed 2010-10-04

- ↑ "Beijing-Shanghai High Speed Line Operated by Chinese Railways". Railway Technology. Archived from the original on 7 June 2011. Retrieved 2011-06-30.

- ↑ "Rail track beats Maglev in Beijing-Shanghai High Speed Railway". English.peopledaily.com.cn. 2004-01-18. Retrieved 2011-06-30.

- ↑ "Beijing-Shanghai High-Speed Line, China". Railway-technology.com. Archived from the original on 7 June 2011. Retrieved 2011-06-30.

- ↑ Report: China to build Beijing-Shanghai high-speed railway soon. International Herald Tribune, September 2008. (accessed: 2008-09-25)

- 1 2 "Beijing-Shanghai high speed line opens". Railway Gazette International. 30 June 2011.

- ↑ Xin, Dingding (8 November 2006). "Social security funds set to be invested in railway". China Daily. Retrieved 2 May 2015 – via HighBeam Research. (subscription required (help)).

- ↑ Zhu, Zhe (13 January 2007). "Financing may delay fast rail project". China Daily. Retrieved 2 May 2015 – via HighBeam Research. (subscription required (help)).

- ↑ "Fast rail looks ready for approval". China Daily. 13 March 2007. Retrieved 2 May 2015 – via HighBeam Research. (subscription required (help)).

- ↑ "Ready to roll: construction is now in full swing on China's massive Beijing--Shanghai high-speed rail project. By 2020, China expects to have a network of eight high-speed lines totalling 10,000km". International Railway Journal. 1 July 2008. Retrieved 3 May 2015 – via HighBeam Research. (subscription required (help)).

- 1 2 "China : 100 Million Passenger Trips for China's High-Speed Railway Line". Mena Report. 2 March 2013. Retrieved 3 May 2015 – via HighBeam Research. (subscription required (help)).

- ↑ (Chinese) "中国北车刷新高铁运营试验世界纪录速度(图)-搜狐证券". Stock.sohu.com. Archived from the original on 20 July 2011. Retrieved 2011-06-30.

- ↑ "Rush to buy tickets for first capital to coast run". China Daily. 25 June 2011. Retrieved 29 June 2011.

- ↑ "Beijing-Shanghai high-speed train makes debut". Google. 29 June 2011. Retrieved 29 June 2011.

- 1 2 "Trains fly on Beijing-Shanghai high-speed railway". Xinhua. 27 June 2011. Retrieved 29 June 2011.

- ↑ "Beijing to Shanghai Railway: diary of a 4h 48m journey". The Daily Telegraph. 27 June 2011. Retrieved 29 June 2011.

- 1 2 Steven Jiang and Haolan Hong) (2011-07-14). "Glitches disrupt China's showpiece high-speed railway". CNN. Retrieved 2011-07-18.

- ↑ "China's high-speed rail glitches: Racing to make errors?". Los Angeles Times. 2011-07-16. Retrieved 2011-07-18.

- ↑ "Air carriers raise prices after high-speed rail lost competitive edge". Xinhua. 2011-07-18. Retrieved 2011-07-18.

- ↑ "Beijing-Shanghai flight prices rebound as high-speed rail deemed no threat". Shanghaiist. 2011-07-18. Retrieved 2011-07-18.

- 1 2 "Ministry apologizes for high-speed train delays". China Daily. 2011-07-15. Archived from the original on 18 July 2011. Retrieved 2011-07-18.

- ↑ "China removed 54 high-speed trains after crash". August 13, 2011.

- ↑ "High-speed rail service ticket prices announced". English.eastday.com. 2011-06-14. Retrieved 2011-06-30.

- ↑ (Chinese) "京沪高速铁路股份有限公司公布京沪高铁动车组列车试行运价". China-mor.gov.cn. 2011-06-14. Retrieved 2011-06-30.

- ↑ Foster, Peter (2011-06-26). "Beijing-Shanghai high-speed rail to open". Vancouversun.com. Retrieved 2011-06-30.

- ↑ Zha, Minjie (2011-06-23). "Beijing-Shanghai high speed rail to be launched June 30". Shanghai Daily. Retrieved 2011-06-25.

- ↑ "China launches new high-speed railway". People's Daily Online. 2012-10-17. Retrieved 2012-11-02.

- ↑ Yang Lifei (2008-01-14). "High speed city link even faster". Shanghai Daily (in English and translated from Chinese article). Shanghai Daily. Retrieved 2008-09-03.

- ↑ "Beijing Shanghai Train". Beijing China Information Portal.

- ↑ (Chinese) 关于京沪高速铁路与沪宁城际铁路昆山段具体走向及站点设置的说明 Archived June 18, 2011, at the Wayback Machine. ("Regarding the tracks alignment and the stations on the Kunshan section of the Beijing-Shanghai High-Speed Railway and the Shanghai-Nanjing Intercity Railway ...")

- 1 2 Longest bridge, Guinness World Records. Last accessed July 2011.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Beijing–Shanghai High-Speed Railway. |

Coordinates: 35°31′45″N 118°48′16″E / 35.5291°N 118.8045°E