Battle of Monterrey

| Battle of Monterrey | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Mexican–American War | |||||||

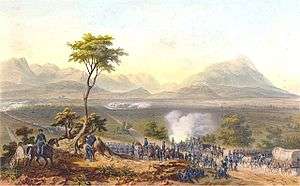

US troops marching on Monterrey during the Mexican–American War, lithograph by Carl Nebel. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Zachary Taylor |

Pedro de Ampudia Jose Garcia-Conde Francisco Mejia | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 6,220[1]:100 | 7,303[1]:100 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

488 killed and wounded (120 killed 368 wounded) 43 missing[1]:100 | 367 killed and wounded[1]:100 | ||||||

In the Battle of Monterrey (September 21–24, 1846) during the Mexican–American War, General Pedro de Ampudia and the Mexican Army of the North was defeated by the Army of Occupation, a force of United States Regulars, Volunteers and Texas Rangers under the command of General Zachary Taylor.

Background

Following the Battle of Resaca de la Palma, Taylor crossed the Rio Grande on 18 May, while in early June, Mariano Arista turned over command of what remained of his army, 2,638 men, to Francisco Mejia, who led them to Monterrey.[1]:82 On 8 June, United States Secretary of War William L. Marcy ordered Taylor to continue command of operations in northern Mexico, suggested taking Monterrey, and defined his objective to "dispose the enemy to desire an end to the war."[1]:86 On 8 August, Taylor established the headquarters for his Army of Occupation in Camargo, Tamaulipas and then in Cerralvo on 9 September with 6.640 men.[1]:88–89 Taylor resumed the march to Monterrey on 11 September, reaching Marin on 15 September and departing on 18 September[1]:90

In early July, General Tomas Requena garrisoned Monterrey with 1,800 men, with the remnants of Arista's army and additional forces from Mexico City arriving by the end of August such that the Mexican forces totaled 7,303 men.[1]:89, 100 General Pedro de Ampudia received orders from Antonio López de Santa Anna to retreat further to the city of Saltillo, where Ampudia was to establish a defensive line, but Ampudia disagreed, sensing glory if he could stop Taylor's advance.[1]:90 Ampudia's forces included reinforcements from Mexico City totaling 3,140 men: 1,080 men of the Garcia-Conde Brigade (Gen. Jose Garcia Conde) (Aguascalientes and Querétaro Battalions, two squadrons of the 3d Line Cavalry, three guns (3-8 lb)), a thousand men of the Azpeitia Brigade (Col. Florencio Azpeitia) (3d Line, two squadrons of the Jalisco lancers, two squadrons of the Guanajuato Cavalry Regiment, six guns (8 and 12 lbs.) and an ambulance), 1,060 men of the Simeon Ramirez Brigade (Acting Gen. Ramirez) (3d and 4th Light, three guns (1-8 lbs, 2-12 lbs) and 3 howitzers 7" (Capt. P. Gutierrez and Comdte. A. Nieto)) and an artillery unit, the largely Irish-American volunteers called San Patricios (or the Saint Patrick's Battalion), in their first major engagement against U.S. forces.

Battle

Taylor's army, with the Texas Division leading under the command of Major General and Texas Governor James Pinckney Henderson, reached the plain in front of Monterrey at 9 am on the morning of 19 September, when they were fired upon by Col. Jose Lopez Uraga's 4th Infantry guns atop the citadel.[1]:92 Taylor ordered the army to camp at Bosque de San Domingo while engineers under the command of Major Joseph K. Mansfield reconnoitered.[1]:92

Besides the citadel, Mexican strong points within the city included: the "Black Fort" commanded by Col. Tyrore Uraga, "the Tannery," La Teneria, with the 2d Ligero under Col. Jose M. Carrasco and the Queretro Battalion under Col. Jose Maria Carrasco, El Fortin del Rincon del Diablo under Lt. Col. Calisto Bravo and Col. Ignacio Joaquin del Arenal, La Purisima bridge and tete-de-pont with the Activos of Aguascalientes under Col. Jose Ferro and the Querétaro under Lt. Col. Jose Maria Herrera.[1]:92 West of the city atop Independencia stood Ft. Libertad and the Obispado (bishop's place) with the Activo of Mexico commanded by Lt. Col. Franciso de Berra, and atop Federacion was a redan and Fort Soldado.[1]:93 In reserve at la Plaza was the 3d Ligero under Lt. Col. Juan Castro and Lt. Agustin Espinosa.

General Zachary Taylor decided to attack western Monterrey using William J. Worth's Division in a giant north and west "hook" movement while simultaneously attacking with his main body from the east.[1]:93 Worth started at 2 pm on 20 September along with Col. John Coffee Hays's Texas Regiment screening the advance, but they camped for the night three miles from the Saltillo road.[1]:93–94

By 6 am on 21 September, Worth continued his advance, repulsing a Jalisco cavalry charge by Col. Juan Najera, and an advance guard consisting of General Manuel Romero's brigade and Lt. Col. Mariano Moret's Guanajuato Regiment.[1]:94 By 8:15 am, Worth had severed the Saltillo road from Monterrey and sent Capt. Charles F. Smith with 300 infantry and Texans, plus Capt. Dixon Miles's 7th Infantry and Persifor Smith's 2nd Brigade to take Federacion and Fort Soldado, which they quickly did.[1]:94

In the meantime, Taylor launched a diversion against eastern Monterrey with Col. John Garland's 1st and 3d Infantry plus Lt. Col. William H. Watson's Maryland and District of Columbia Battalion, which quickly grew into an assault.[1]:95 By 8 am, Capt. Electus Backus's company of the 1st Infantry had taken the tannery and by noon, with Col. William B. Campbell's 1st Tennessee and Mississippi Rifles, had taken Fort de La Teneria.[1]:96[2][3]

No attacks or sorties occurred on 22 September.[1]:97

At 3 am on 23 September, Worth sent the Texas Rangers and the 4th and 8th Infantry, under Lt. Col. Thomas Childs, to take Fort Libertad on Independencia, which they did by daybreak.[1]:97 With the help of James Duncan's battery, they soon took the Obispado and had control of western Monterrey.[1]:97[2] By then, the Mexicans had abandoned their outer defenses on the east side of Monterrey, concentrating in the Plaza Mayor, and John A. Quitman's brigade held eastern Monterrey by 11 am.[1]:97,99

By 2 pm on 23 September, General Worth advanced into the city from the west, burrowing house to house, supported in the late afternoon by a mortar set up in Plaza de la Capella, and were within a block west of the plaza by 11 pm.[1]:99 The Texan volunteers taught the U.S. regulars new techniques for fighting in the city, techniques that they did not employ on 21 September, which led to staggering casualties. Armed with these new urban warfare skills, the U.S. Army, along with Texan, Mississippian, and Tennessee volunteers moved house to house, rooting out Mexican soldiers hiding on rooftops and inside the thick, adobe-walled houses of northern Mexico.[4][5] By 2 pm, Taylor and Quitman were within two blocks east of the plaza when Taylor ordered a withdrawal before nightfall.[1]:99

General Ampudia decided to negotiate on 24 September.[1]:99 Taylor negotiated a two-month armistice, along the line Rinconada Pass-Linares_San Fernando de Parras, in return for the surrender of the city.[1]:100 The Mexican Army was allowed to march from the city from 26 to 28 September, with their personal arms and one field battery of six guns.[1]:99, 101

Aftermath

Ampudia had moved beyond the armistice line by 30 September and San Luis Potosi by early November.[1]:101

The resulting armistice signed between Taylor and Ampudia had major effects upon the outcome of the war. Taylor was lambasted by some in the federal government, where President James K. Polk insisted that the U.S. Army had no authority to negotiate truces, only to "kill the enemy." In addition, his terms of armistice, which allowed Ampudia's forces to retreat with battle honors and all of their weapons, were seen as foolish and short-sighted by some U.S. observers. For his part, some have argued that Ampudia had begun the defeat of Mexico. Many Mexican soldiers became disenchanted with the war. In a well-fortified, well-supplied position, an army of ten thousand Mexican soldiers had resisted the U.S. Army for three days, only to be forced into surrender by American urban battle tactics, heavy artillery and possibly further division in the Mexican ranks.

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 Bauer, K.J., 1974, The Mexican War, 1846-1848, New York:Macmillan, ISBN 0803261071

- 1 2 Chris Dishman, "Street Fight in Monterrey," Military Heritage Magazine, August 2009. Archived July 14, 2011, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Valtier, Ahmed. “Fatídica Orden: Asalto Yanqui Sobre Monterrey.” Atisbo, Year 1, vol. 4 (September 2006).

- ↑ Chris Dishman, "Street Fight in Monterrey," Military Heritage Magazine, August 2009 Archived July 14, 2011, at the Wayback Machine.\.

- ↑ Urban Warfare at Monterrey — Battleofmonterrey.com

- ↑ Smith, J.H., 1919, The War with Mexico, New York:Macmillan

Further reading

- Toro, Alfonso "Historia de México", vol. 2, pp. 372–374.

- Alcaraz, Ramon et al. "Apuntes Para la Historia de la Guerra Entre Mexico y los Estados Unidos"

- Balbotin, Manuel "La Invasion Americana, 1846 a 1848"

- Grant, U.S. "Personal Memoirs of U.S. Grant, Vol I, pp 74-82", ISBN 0-940450-58-5

- Note 1 Alcaraz in "Apuntes..." lists the initial Mex. units on pp 90–91.

- Note 2 Balbontin in " La Invasion" lists the Mex. reinforcements on pp 10–11. He lists units and artillery at some of the defense points.

- Annual Reports 1894, War Department list trophy guns as: 1- 12 pounder, 3- 8 pounders, 2- 4 pounders, 2- 4 pounder mountain howitzers & 1- 68 pound howitzer.

- Eisenhower, John S. D. (1989). So Far from God, The U.S. War with Mexico, 1846-1848. Random House. ISBN 978-0-8061-3279-2.

- Dishman, Christopher, ''A Perfect Gibraltar: The Battle for Monterrey, Mexico," University of Oklahoma Press, 2010 ISBN 0-8061-4140-9

- Gateway South: The Campaign for Monterrey. U.S. Army Center of Military History.

External links

- The Capture of Monterrey - PBS U.S.-Mexican War

- The Battle of Monterrey - A Continent Divided: The U.S.-Mexico War, Center for Greater Southwestern Studies, University of Texas at Arlington

- Nuevo Leon, Historic Sites of the U.S.-Mexican War - Descendants of Mexican War Veterans

- Battle for Monterrey, Mexico

- Mexican-American War remains arrive in U.S. for study

Coordinates: 25°40′56″N 100°18′40″W / 25.6822°N 100.3111°W