Battle of Lindley's Mill

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

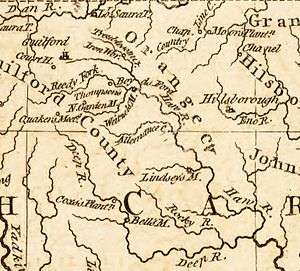

The Battle of Lindley's Mill (also known as the Battle of Cane Creek) took place in Orange County, North Carolina (now in Alamance County), on September 13, 1781, during the American Revolutionary War. The battle took its name from a mill that sat at the site of the battle on Cane Creek, which sat along a road connecting what was then the temporary state capital, Hillsborough, with Wilmington, North Carolina.

Background

On September 12, 1781, loyalist militia under the command of militia colonels David Fanning and Hector McNeill captured Governor Thomas Burke and thirteen high-ranking Whig officials in a daylight raid on Hillsborough on September 12, 1781. The captured officials were to be transported down the road to Wilmington where they would be turned over to the British Army.[2] Brigadier General John Butler, whose home was located nearby,[3] and 300 patriot militiamen of the Hillsborough District Brigade set an ambush at Lindley’s Mill the next day.[2]

The battle

Lindley's Mill was located on Cane Creek, a tributary of the Haw River. Upon the Loyalist approach, the Patriot militia sprung their trap, surprising Fanning and his men. The loyalist forces were forced to ford Cane Creek in order to assault the patriot positions, which were on a plateau overlooking the creek.[4] The elderly Hector McNeill, the commander of a unit of loyal Highlanders, was cut down early in the battle, leading the vanguard of Fanning's militia across the creek. The British failed to gain any ground against the Patriot position until Fanning and a larger company forded the creek upstream from Butler's position, and attacked the Patriot militia from their flank.[2] This put the militia on the defensive, and the battle persisted for four hours[5] until eventually Butler felt compelled to order his men to retreat due to casualties.[6] In spite of Butler's order, a contingent of men attempted to continue holding their ground, but they were ultimately dislodged by Fanning.[7]

Aftermath

Between 200 and 250 men were killed or wounded in the battle, with the Tory force suffering due to the loss of McNeill and serious wounds received by Fanning, who was forced to hide in the woods when his column moved on. Among those wounded was Dr. John Pyle, who had earlier commanded an ill-fated regiment of loyalist militia at Pyle's Massacre. After recovering from his wounds, Pyle helped to nurse many other wounded men, patriots and loyalists alike, back to health, for which service Governor Alexander Martin would later pardon Pyle's loyalist activities.[6] The governor was not rescued by the patriots, and was successfully imprisoned on James Island.[8] The battle effectively closed the war in North Carolina one month before Lord Cornwallis surrendered the British Army at Yorktown, but did not serve to dampen patriot sentiments in the State. Indeed, historians have commented that the capture of Governor Burke and the defeat of the patriots only encouraged a growth in patriot sentiment.[6]

See also

References

Citations

- 1 2 Rankin 1971, p. 365.

- 1 2 3 Butler 2006.

- ↑ Caruthers 2010, p. 113.

- ↑ Caruthers 2010, p. 114.

- ↑ Butler 1979, p. 290.

- 1 2 3 "Marker: G-21 - LINDLEY'S MILL". North Carolina Highway Historical Marker Program. North Carolina Department of Cultural Resources. Retrieved 21 December 2012.

- ↑ Caruthers 2010, p. 115–116.

- ↑ Rodenbough 2004, p. 66.

Sources

- Butler, Lindley S. (1979). "Butler, John". In Powell, William S. Dictionary of North Carolina Biography. Volume 1 (A-C). Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-8078-1806-0.

- Butler, Lindley (2006). "Lindley's Mill, Battle of". In Powell, William S. Encyclopedia of North Carolina. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-8078-3071-0.

- Caruthers, E.W. (2010). Fryar, Jr., Jack E., ed. Revolutionary Incidents: Sketches of Character, Chiefly in the Old North State. Volume 1. Wilmington, NC: Dram Tree Books. ISBN 978-0-8078-1154-2.

- Newlin, Algie I. (1975). The Battle of Lindley's Mill. Burlington, NC: The Alamance Historical Association. OCLC 1340591.

- Rankin, Hugh F. (1971). The North Carolina Continentals. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-8078-1154-2.

- Rodenbough, Charles D. (2004). Governor Alexander Martin: Biography of a North Carolina Revolutionary War Statesman. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company. ISBN 0-7864-1684-X.