Battle of Ia Drang

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

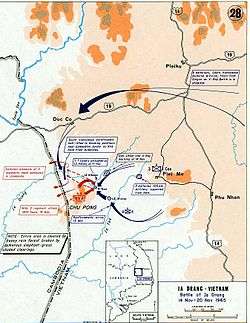

The Battle of Ia Drang comprises two main engagements conducted by the 1st Battalion, 7th Cavalry Regiment that took place on November 14–15, 1965 at LZ X-Ray ("eastern foot of the Chu Pong massif"[16]) and by the 2nd Battalion, 7th Cavalry Regiment on November 17 at LZ Albany further north in the Ia Drang Valley. It was the first major battle[5] between the United States Army and the North Vietnamese Army-NVA (People's Army of Vietnam-PAVN) during the Vietnam War as part of the U.S. airmobile offensive code-named Operation Silver Bayonet I (October 23 – November 18, 1965). The battle was part of the second phase of a search-and-destroy operation code-named "Operation Long Reach" that took place from October 23 to November 26 during the Pleiku Campaign.[5]

The battle derives its name from the Drang River which runs through the valley west of Plei Me, where the engagement took place (Ia means "river" in the local Montagnard language). Representing the American forces were elements of the 3rd and 2nd Brigades, 1st Cavalry Division (Airmobile): the 1st and 2nd Battalion, 7th Cavalry, and the 2nd Battalion, 5th Cavalry. Representing the North Vietnam forces were elements of the B3 Front of the NVA (including the 304th Division). The battle involved close air support by U.S. Army helicopter gunships and U.S Air Force and U.S. Navy tactical jet aircraft, and a bombing attack by Air Force B-52s.

The initial North Vietnamese assault against the 1st Battalion, 7th Cavalry landing at LZ X-Ray was repulsed after two days and nights of heavy fighting on November 14–16, with the Americans inflicting heavy losses on North Vietnamese regulars. In a follow-up surprise attack on November 17, the North Vietnamese overran the marching column of the 2nd Battalion, 7th Cavalry near LZ Albany in the most successful ambush against U.S. forces of the war. Both sides suffered heavy casualties; the U.S. had nearly 250 soldiers killed but claimed to have counted about 1,000 North Vietnamese bodies on the battlefield and estimated that more were killed by air strikes and artillery. General Knowles, Forward CP Commander, 1st Cavalry Division (Airmobile), did not see the engagement as an ambush, but as a "meeting engagement".[17]

The battle at LZ X-Ray was documented in the CBS special report Battle of Ia Drang Valley by Morley Safer and the critically acclaimed book We Were Soldiers Once... And Young by Harold G. Moore and Joseph L. Galloway. In 2002, Randall Wallace depicted the battle at LZ X-Ray in the film We Were Soldiers starring Mel Gibson and Barry Pepper as Moore and Galloway, respectively. Galloway later described this battle that he calls 'Ia Drang' as "The battle that convinced Ho Chi Minh he could win"; Ho Chi Minh was the leader of North Vietnam at the time.[11]

Background

In 1963 and 1964, a series of political and military mishaps had seriously affected the capabilities of the South Vietnamese Army's (ARVN) main forces in South Vietnam. ARVN commanders were initially under the direct orders from President Ngo Dinh Diem to avoid pitched combat at all costs, which allowed the National Liberation Front (NLF) forces known as the Viet Cong or "VC" (Vietnamese Communists), to train and grow without significant opposition, despite losing several leaders to CIA search and destroy squads, which relied heavily on rocket attacks using helicopters. After Diem's overthrow in a 1963 coup, the new military leadership largely consisted of commanders put in place by Diem prior to the coup. They showed equal lack of interest in fighting the NLF, spending their time in a series of coups and counter-coups. In this unstable political climate, the NLF (VC) units were able to mount increasingly larger military operations. At first these were limited to building up larger formations (battalions and regiments), but by late 1964 they had evolved into an all-out war against ARVN units, which they outperformed in every way.

At the end of 1964, Chairman Mao Zedong of the People's Republic of China turned on the green light for the Viet Cong to upgrade attacking forces to division size in its conquest of South VietNam. In the meeting dated October 5, 1964, Mao Zedong told Pham Van Dong: "According to Comrade Le Duan, you had the plan to dispatch a division [to the South]. Probably you have not dispatched that division yet. When should you dispatch it, the timing is important."[18] In the Pleime campaign, the PAVN received money, food and equipment supplies, military advisors and signal specialists from China, with the establishment of a Chinese Advisors headquarters in Phnom Penh, Cambodia,

The natural corridors often mentioned by General Delange in 1951 would not be efficient without the existence of Cambodia, without rice from the Tonlé sap lake, without the concealment of Red Chinese advisors who enjoyed full amenities living in Phnom Penh, without the excellent communication by ways of telephone and airgram between Phnom Penh and Hanoi.[19]

In 1965, the NVA's 304th Division received orders to prepare to infiltrate South Vietnam,

Early 1965, the Joint General Staff summoned me and the 304th division commander to give us the order to enter the South on a combat mission.[20]

By early 1965, the majority of rural South Vietnam was under limited Viet Cong (VC) control, increasingly supported by Vietnam People's Army (PAVN) regulars from North Vietnam, while the Republic of Vietnam's (South Vietnam) ARVN units in the field were hopelessly outclassed and entire units were ambushed and slaughtered. American advisers in the field had long been pushing for South Vietnamese Army forces to be "taken over" by U.S. commanders. In addition to actually getting the men to fight (something they generally seemed willing to do when well-led), the U.S. command's better training and leadership were expected to be more than enough to make up for the deficiencies of the ARVN command. The new commander in South Vietnam, General William Westmoreland, felt the direct application of U.S. forces was a more appropriate solution; perhaps the ARVN units would not fight, but the same was certainly not true of the U.S. military. By early 1965, Westmoreland had secured the commitment of upward of 300,000 U.S. regulars from Lyndon B. Johnson and a build-up of forces took place in the summer of 1965.

Viet Cong forces were in nominal control of most of the South Vietnamese countryside by 1965 and had established military infrastructure in the Central Highlands, to the north-east of the Saigon region. Vietnamese communist forces had operated in this area during the previous decade in the First Indochina War against the French, winning a notable victory at the Battle of Mang Yang Pass in 1954. There were few reliable roads into the area, making it an ideal place for the communist forces to form bases, relatively immune from attack by the generally road-bound ARVN forces. During 1965, large groups of North Vietnamese Army regulars moved into the area, to conduct offensive operations. Attacks to the south-west from these bases threatened to cut South Vietnam in two. The U.S. command saw this as an ideal area to test new air mobility tactics.

Air mobility called for battalion-sized forces to be delivered, supplied and extracted from an area of action using helicopters. Since the heavy weapons of a normal combined-arms force could not follow, the infantry would be supported by coordinated close air support, artillery and aerial rocket fire, arranged from a distance and directed by local observers. They had been practising these tactics in the U.S. in the new 11th Air Assault Division (Test). The 11th was renamed the 1st Cavalry Division (Airmobile), which had been in South Korea since the Korean War. The 1st Cavalry Division's reflagged units became the 2nd Infantry Division and the 1st Cavalry's colors were transferred to the 11th Air Assault (Test) at Fort Benning, just before deployment overseas.

The division's troopers dubbed themselves the "Air Cav" (Air Cavalry)) and in July 1965 began deploying to Camp Radcliff, An Khê, Vietnam. By November, most of the division's three brigades were ready for operations. It was this U.S. troop build-up that caused B3 Field Front Command to launch earlier (on October 19, 1965) the attack of the Pleime camp which had been planned for December, with only the two 32nd and 33rd Regiments, instead of the planned three regiments (the 66th would only reach the battlefield by mid November), before the Air Cavalry troops were combat ready.

In August 1965, the NVA 304th Division received order to intensify preparation to go to Central Highlands by September:

Early August 1965, the Defense Ministry gave the order to 304th Division Commander ... to bring the entire 304th Division to battlefront B… all preparations must be achieved within two months.[21]

In September 1965, II Corps Command/J2 MACV studied plan to destroy the NVA B3 Field Front forces at their bases in Chu Pong, where the staging area[22] was set for the attack of the Pleime camp, by B-52 strike:

The Chu Pong base was known to exist well prior to the Pleime attack and J2 MACV had taken this area under study in September 1965 as a possible B-52 target.[23]

On October 19, the NVA attacked the Pleime camp with the 33rd and 32nd regiments[24] and on October 26, with the siege at Pleime lifted, ARVN II Corps Command requested that "1st Cav TAOR be extended to include the Plei Me area except the camp itself".[25] and be assigned the Trường Chinh (Long Reach) operation[26] This operation was carried out in three parts: All the Way (1st Brigade), Silver Bayonet I (3rd Brigade) and Silver Bayonet II (2nd Brigade).[27] On November 10, the 3rd Brigade, 1st Cavalry Division (Airmobile) replaced the 1st Brigade of the division and was ordered to perform a diversionary maneuver by switching the operational direction to the east to entice B3 Field Front to regroup its three regiments in assembly areas, to stage a second attack of Pleime camp set for November 16.[28][29]

With American units seemingly withdrawing to the east of Pleime, the decision was to attempt to regain its early advantage with an attack. The target once again was the Pleime CIDG Camp. The division headquarters set the date for attack at 16 November, and issued orders to its three regiments.[30]

On November 11, intelligence source revealed the disposition of the three NVA regiments: the 66th at vicinity YA9104, the 33rd at YA 940010 and the 32nd at YA 820070.[31] On November 12, the 3rd Brigade was given order to prepare for "an air assault near the foot of the Chu Pongs",[32] at 13°34′11″N 107°40′54″E / 13.56972°N 107.68167°E, 14 miles (22 km) northwest of Plei Me. On November 13, 3rd Brigade Commander Colonel Thomas W. Brown met with Lieutenant Colonel Hal Moore the commander of the 1st Battalion, 7th Cavalry Regiment, and told him "to conduct an airmobile assault the following morning"[33] and to conduct search and destroy operations through 15 November.

- Landing zones

Col. Brown selected Lt. Col. Moore and his men for the mission, with the explicit orders to not attempt to scale the mountain. There were several clearings in the area that had been designated as possible helicopter landing zones, typically named for a letter of the NATO phonetic alphabet. Moore selected:

- LZ X-Ray: at 13°34′4.6″N 107°42′50.4″E / 13.567944°N 107.714000°E as his landing zone, a flat clearing surrounded by low trees at the eastern base of the Chu Pong Massif and bordered by a dry creek bed on the west. The Ia Drang River was about 2 km (1 mi) to the northwest.

- LZ Albany: about 2.5 km (2 mi)to the northeast of X-Ray at 13°35′43″N 107°42′55″E / 13.59528°N 107.71528°E

- LZ Columbus: about 2.2 km (1 mi) east of Albany at 13°35′20.8″N 107°44′29″E / 13.589111°N 107.74139°E

- LZ Tango: about 2 km (1 mi) to the north of X-Ray at 13°35′28.8″N 107°42′46″E / 13.591333°N 107.71278°E

- LZ Yankee: a similar distance south of X-Ray at 13°33′14.1″N 107°43′1.3″E / 13.553917°N 107.717028°E. LZ Yankee was on sloping ground and could only fit about 6–8 helicopters at one time.

- LZ Whiskey: 2.1 km (1 mi) south-east at 13°33′17.8″N 107°43′40.8″E / 13.554944°N 107.728000°E

- LZ Victor: at 13°33′33″N 107°43′47.8″E / 13.55917°N 107.729944°E about 6 km (4 mi) to the south-southeast.

Artillery support would be provided from firebase "FB Falcon", about 8 km (5 mi) to the northeast of X-Ray at 13°37′22″N 107°45′51″E / 13.62278°N 107.76417°E.

LZ X-Ray was approximately the size of a misshapen football field, some 100 meters in length (east to west). It was estimated that only eight UH-1 Hueys could fit in the clearing at a given time. The 1st Battalion, 7th Cavalry (1/7) was typical for U.S. Army units of the time, consisting of three rifle companies and a heavy weapons company: A-Alpha Company, B-Bravo Company, C-Charlie Company, and D-Delta Company... about 450 men in total of the 765 of the battalion's authorized strength. They were to be shuttled by 16 Huey transport helicopters, which could generally carry 10 to 12 equipped troopers, so the battalion would have to be delivered in several "lifts" carrying just less than one complete company each time. Each lift would take about 30 minutes. Lt. Col. Moore arranged the lifts to deliver Bravo Company first, along with his command team, followed by Alpha and Charlie Companies, and finally Delta Company. Moore's plan was to move Bravo and Alpha Companies northwest past the creek bed, and Charlie Company south toward the mountain. Delta Company, which comprised special weapons forces including mortar, recon, and machine gun units, was to be used as the battlefield reserve. In the center of the LZ was a large termite hill that was to become Moore's command post.

LZ X-Ray

Day 1: Nov. 14, 1965

Landings

At 10:48 on November 14, the first troops of the 1st Battalion, 7th Cavalry (1/7) arrived at LZ X-Ray with members of B Company touching down after about 30 minutes of bombardment via artillery, aerial rockets, and air strikes. Accompanying Captain John Herren's B Company were Lt. Col. Moore and his 1st Battalion command group. Instead of attempting to secure the entire landing zone with such a limited force, most of B Company was kept near the center of the LZ as a strike force, while smaller units were sent out to reconnoiter the surrounding area.

B3 Field Front Command fell for the subterfuge, decided to postpone the attack of Pleime camp and met the new threat with its 7th and 9th Battalions.[34]

Following their arrival, Capt. Herren ordered B Company to move west past the creek bed. Within approximately 30 minutes, one of his squads under Sergeant John Mingo surprised and captured an unarmed deserter of the 33rd NVA Regiment. The prisoner revealed that there were three North Vietnamese Army battalions on the Chu Pong Mountain – an estimated 1,600 North Vietnamese troops compared to fewer than 200 American soldiers on the ground at that point. At 11:20, the second lift from the 1st battalion arrived, with the rest of B Company and one platoon of Captain Tony Nadal's A Company. Fifty minutes later, the third lift arrived, consisting of the other two platoons of A Company. A Company took up positions to the rear and left flank of B Company along the dry creek bed, and to the west and to the south facing perpendicular down the creek bed.

At 12:15, the first shots were fired on the three platoons of B Company that were patrolling the jungle northwest of the dry creek bed. Five minutes later, Capt. Herren ordered his 1st Platoon under Lieutenant Al Devney and 2nd Platoon under Lieutenant Henry Herrick to advance abreast of each other and the 3rd Platoon (under Lieutenant Dennis Deal) to follow as a reserve unit. Lt. Devney's 1st Platoon led approximately 100 yards (91 m) west of the creek bed, with Herrick's 2nd Platoon to his rear and right flank. Just before 13:00, Devney's 1st platoon was heavily assaulted on both flanks by the North Vietnamese, taking casualties and becoming pinned down in the process. It was around this point that Lt. Herrick radioed in that his 2nd Platoon were taking fire from their right flank, and that he was pursuing a squad of communist forces in that direction.

Herrick's platoon is cut off

In pursuit of the North Vietnamese on his right flank, Lt. Herrick's 2nd Platoon, B Company, was quickly spread out over a space of around 50 meters, and became separated from the rest of 1/7 by approximately 100 meters. Soon, Lt. Herrick radioed in to ask whether he should enter or circumvent a clearing that his platoon had come across in the bush. Lt. Herrick expressed concerns that he might become cut off from the battalion if he tried to skirt the clearing and therefore would be leading his men through it in pursuit of the enemy. An intense firefight quickly erupted in the clearing; during the first three or four minutes his platoon inflicted heavy losses on the North Vietnamese who streamed out of the trees, while his men did not take any casualties. Lt. Herrick soon radioed in that the enemy were closing in around his left and right flanks. Capt. Herren responded by ordering Lt. Herrick to attempt to link back with Devney's 1st Platoon. Herrick replied that there was a large enemy force between his men and 1st Platoon. The situation quickly disintegrated for Lt. Herrick's 2nd Platoon, which began taking casualties as the North Vietnamese attack persisted. Herrick ordered his men to form a defensive perimeter on a small knoll in the clearing. Within approximately 25 minutes, five men of 2nd Platoon were killed, including Lt. Herrick who radioed Capt. Herren that he was hit and was passing command over to Sergeant Carl Palmer. Lt. Herrick gave vital instructions to his men before he died, including orders to destroy the signals codes and call in artillery support. Sergeant Ernie Savage, 3rd Squad Leader, assumed command after Sergeant Palmer and Sergeant Robert Stokes were killed. The 2nd Platoon was technically under the command of Sergeant First Class Mac McHenry, who was positioned elsewhere on the perimeter. Sgt. Savage assumed command by virtue of being close to the radio and began the process of calling in repeated bombardments of artillery support around the 2nd Platoon's position. By this point, eight men of the platoon had been killed and 13 wounded.

Under Sgt. Savage's leadership, and with the extraordinary care of the 2nd Platoon's medic Charlie Lose, the platoon held the knoll for the duration of the battle at X-Ray. Specialist Galen Bungum, 2nd Platoon, B Company, later said of the stand at the knoll: "We gathered up all the full magazines we could find and stacked them up in front of us. There was no way we could dig a foxhole. The handle was blown off my entrenching tool and one of my canteens had a hole blown through it. The fire was so heavy that if you tried to raise up to dig you were dead. There was death and destruction all around."[35]:117,118 Sgt. Savage later recalled of the repeated NVA assaults: "It seemed like they didn't care how many of them were killed. Some of them were stumbling, walking right into us. Some had their guns slung and were charging bare-handed. I didn't run out of ammo – had about thirty magazines in my pack. And no problems with the M16. An hour before dark three men walked up on the perimeter. I killed all three of them 15 feet away."[35]:168

Fight for the creek bed

With 2nd Platoon, B Company cut off and surrounded, the rest of 1/7 fought to maintain a perimeter. At 13:32, C Company under Captain Bob Edwards arrived, taking up positions along the south and southwest facing the mountain. At around 13:45, through his Operations Officer flying above the battlefield (Captain Matt Dillon), Lt. Col. Moore called in air strikes, artillery, and aerial rocket artillery on the mountain to prevent the North Vietnamese from advancing on the battalion's position.

Lieutenant Bob Taft's 3rd Platoon, A Company, confronted approximately 150 Vietnamese soldiers advancing down the length and sides of the creek bed (from the south) toward the battalion. The platoon's troopers were told to drop their packs and move forward for the assault. The resulting exchange was particularly costly for the platoon — its lead forces were quickly cut down. 3rd Platoon was forced to pull back, and its leader Lt. Taft was killed. Sergeant Lorenzo Nathan, a Korean War veteran, took command of 3rd Platoon which was able to halt the NVA advance down the creek bed. The NVA forces shifted their attack to 3rd Platoon's right flank in an attempt to flank B Company. Their advance was quickly stopped by Lt. Walter "Joe" Marm's 2nd Platoon, A Company, situated on B Company's left flank. Lt. Col. Moore had ordered Captain Nadal (A Company) to lend B Company one of his platoons, in an effort to allow Capt. Herren (B Company) to attempt to fight through to Lt. Herrick's (2nd Platoon, B Company) position. From Lt. Marm's (2nd Platoon, A Company) new position, his men killed some 80 NVA troops with a close range machine gun, rifle, and grenade assault. The NVA survivors who were not mowed down made their way back to the creek bed, where they were cut down by additional fire from the rest of A Company. Lt. Taft's (3rd Platoon, A Company) dog tags were discovered on the body of a NVA soldier who had been killed by Taft's platoon. Upset that Lt. Taft's body had been left on the battlefield amidst the chaos, Capt. Nadal (A Company commander) and his radio operator, Sergeant Jack Gell, brought Lt. Taft and the bodies of other Americans back to the creek bed under heavy fire.

Attack from the south

At 14:30 hours, the last troops of C Company (1/7) arrived, along with the lead elements of D Company (1/7) under Captain Ray Lefebvre. The insertion took place with intense NVA fire pouring into the landing zone, and the Huey crews and newly arrived 1/7 troopers suffered many casualties. The small contingent of D Company took up position on A Company's left flank. C Company, assembled along the south and southwest in full strength, was met within minutes by a head-on assault. C Company's commander, Capt. Edwards, radioed in that an estimated 175 to 200 NVA troops were charging his company's lines. With a clear line of sight over their sector of the battlefield, C Company was able to call in and adjust heavy ordnance support with precision, inflicting devastating losses on the Vietnamese forces. Many NVA soldiers were burned to death as they scrambled from their bunkers in a hasty retreat only to meet a second barrage of artillery shells. By 15:00 the attack had been quelled, and the NVA ended up withdrawing from the assault approximately one hour after it had been launched.

Attack on Alpha and Delta Companies

At approximately the same time, A Company and the lead elements of D Company (which had accompanied Alpha Company at the perimeter in the vicinity of the creek bed) were met by a fierce NVA attack. Covering the critical left flank from being rolled up by the North Vietnamese were two of A Company's machine gun crews positioned 75 yards (69 m) southwest of the company's main position. Specialist Theron Ladner (with his assistant gunner Private First Class Rodriguez Rivera) and Specialist 4 Russell Adams (with a-gunner Specialist 4 Bill Beck) had positioned their guns 10 yards (9.1 m) apart, and proceeded to pour heavy fire into the North Vietnamese forces attempting to cut into the perimeter between C and A Companies. Lt. Col. Moore later credited the two gun teams with preventing the NVA from rolling up Alpha Company and driving a wedge into the battalion between Alpha and Charlie Companies. Spec. 4 Adams and Pfc. Rivera were severely wounded in the onslaught. After the two were carried to the battalion's collection point at Lt. Col. Moore's command post to await evacuation by air, Spec. 4 Beck, Spec. Ladner, and Pfc. Edward Dougherty (an ammo-bearer) continued their close range suppression of the Vietnamese advance. Spec. 4 Beck later said of the battle: "When Doc Nall was there with me, working on Russell, fear, real fear, hit me. Fear like I had never known before. Fear comes, and once you recognize it and accept it, it passes just as fast as it comes, and you don't really think about it anymore. You just do what you have to do, but you learn the real meaning of fear and life and death. For the next two hours I was alone on that gun, shooting at the enemy."[35]:133

Delta Company's troopers also experienced heavy losses in repelling the NVA assault, and Captain Lefebvre was wounded soon after arriving at LZ X-Ray. One of his platoon leaders, Lieutenant Raul Taboada was also severely wounded, and Capt. Lefebvre passed command of D Company to Staff Sergeant George Gonzales (who, unknown to Lefebvre, had also been wounded). While medical evacuation helicopters (medevacs) were supposed to transport the battalion's growing casualties, only two were evacuated by medevacs before the pilots called off their mission under intense fire from the NVA. Casualties were loaded onto the assault Hueys (lifting the battalion's forces to X-Ray), whose pilots carried load after load of wounded from the battlefield. 1st Battalion, 7th Cavalry's intelligence officer Captain Tom Metsker (who had been wounded) was fatally hit when helping Capt. Lefebvre aboard a Huey.

360-degree perimeter

Captain Edwards (C Company) ordered SSgt. Gonzales who had been given command of D Company by its commander, to position D Company on C Company's left flank, extending the perimeter to cover the southeast side of X-Ray. At 15:20, the last of the 1st battalion arrived, and Lieutenant Larry Litton assumed command of D Company. It was during this lift that one Huey, having approached the landing zone too high, crash-landed on the outskirts of the perimeter near the command post (those on board were quickly rescued by the battalion). With Delta Company's weapons teams on the ground, its mortar units were massed with the rest of the battalion's in a single station to support Alpha and Bravo Companies. D Company's reconnaissance platoon (commanded by Lieutenant James Rackstraw) was positioned along the north and east of the landing zone, establishing a 360-degree perimeter over X-Ray. Had the NVA forces circled around to the north of the U.S. positions prior to this point, they would have found their approach unhindered.

Second push to the lost platoon

As the NVA attack on Alpha Company diminished, Lt. Col. Moore organized another effort to rescue 2nd Platoon, B Company. At 15:45, Moore ordered Alpha Company and Bravo Company to evacuate their casualties and pull back from engagement with the enemy. Shortly after, Alpha and Bravo Companies began their advance from the creek bed toward 2nd Platoon, B Company and soon suffered casualties. At one point, B Company's advance was halted by a firmly entrenched North Vietnamese machine gun position at a large termite hill. Lt. Marm, 2nd Platoon, A Company, fired a light anti-tank weapon (LAW) at the machine-gun position, charged the position with grenades under fire, and eliminated the remaining NVA at the machine-gun position with rifle fire. The following day, a dozen dead NVA troops (including one officer) were found in the position. Lt. Marm was wounded in the neck and jaw in the assault and was later awarded the Medal of Honor for his lone assault.[36] The second push had advanced just over 75 yards (69 m) toward the lost platoon's position before reaching a stalemate with the NVA. At one point, the NVA were firing on Alpha Company's 1st Platoon which was leading the advance and was at risk of becoming separated from the battalion, with an American M60 machine gun that had been taken from a dead gunner of Lt. Herrick's and Sgt. Savages 2nd Platoon. The stalemate lasted between 20 and 30 minutes before Captains Nadal (A Company) and Herren (B Company) requested permission to withdraw back to X-Ray (to which Moore agreed).

Americans dig in for the night

Near 17:00 hours, the lead elements of Bravo Company of 2nd Battalion, 7th Cavalry (2/7) arrived at LZ X-Ray to reinforce the embattled 1st Battalion. In preparation for a defensive position to last the night, Lt. Col. Moore ordered Bravo Company's commander Captain Myron Diduryk to place two of his platoons between B/1/7 and D/1/7 on the northeast side of the perimeter. Capt. Diduryk's 2nd Platoon, B Company (under Lt. James Lane), was used to reinforce C/1/7's position (which was stretched over a disproportionately long line). By nightfall, the battle had taken a heavy toll on Lt. Col. Moore's battalion: B/2/7 had taken 47 casualties (including one officer) and A Company had taken 34 casualties (including three officers); C company had taken only four casualties.

The American forces were placed on full alert throughout the night. Under the light of a bright moon, the North Vietnamese probed every company on the perimeter (with the exception of D/1/7) in small squad-sized units. The Americans exercised some level of restraint in their response. The M60 gun crews, tactically positioned around the perimeter to provide for multiple fields of fire, were told to hold their fire until otherwise ordered (so as to conceal their true location from the NVA). Second Platoon of B Company (1/7) under the leadership of Sgt. Savage, suffered three sizable assaults of the night (one just before midnight, one at 03:15, and one at 04:30). The NVA, using bugles to signal their forces, were repelled from the knoll with artillery, grenade, and rifle fire. Savage's "lost platoon" survived the night without taking additional casualties.

Day 2: Nov. 15

Attack at dawn

Just before dawn at 06:20, Lt. Col. Moore ordered his battalion's companies to put out reconnaissance patrols to probe for North Vietnamese forces. At 06:50, patrols from Charlie Company's 1st Platoon (under Lieutenant Neil Kroger) and 2nd Platoon (under Lieutenant John Geoghegan) had advanced 150 yards (140 m) from the perimeter before coming into contact with NVA troops. A firefight broke out, and the patrols quickly withdrew to the perimeter. Shortly after, an estimated 200-plus North Vietnamese Army troops charged 1st and 2nd Platoons of C Company on the south side of the perimeter. Heavy ordnance support was called in, but the NVA were soon within 75 yards (69 m) of the 1st Battalion's lines. Their fire began to cut through Charlie Company's positions and into the command post and the American lines across the LZ. 1st and 2nd platoons suffered significant casualties in this assault, including Lt. Kroger and Lt. Geoghegan. Lt. Geoghegan was killed while attempting to rescue one of his wounded men, Pfc. Willie Godboldt (who died of his wounds shortly thereafter). Two M60 crews (under Specialist James Comer and Specialist 4 Clinton Poley, Specialist 4 Nathaniel Byrd, and Specialist 4 George Foxe) were instrumental in suppressing the North Vietnamese advance from completely overrunning Lt. Geoghegan's lines. Following this attack, Charlie Company's 3rd Platoon under Lt. William Franklin was soon met with a NVA assault. C Company's commander, Capt. Edwards was seriously wounded, and Lt. John Arrington assumed command of the company and was himself wounded while receiving instructions from Edwards. C Company's command then passed to Platoon Sergeant Glenn A. Kennedy. Lt. Franklin was also seriously wounded. The battalion was being attacked in two directions.

Three-pronged attack

At 07:45, the NVA launched an assault on Crack Rock, near its connection with the beleaguered C/1/7. Enemy fire started to penetrate the 1st Battalion's command post, which suffered a medic being killed and several wounded (including one of Lt. Col. Moore's own radio operators, Specialist 4 Robert Ouellette). Under heavy attack on three sides, the battalion fought off repeated waves of NVA infantry. It was during this battle that Specialist Willard Parish of Charlie Company, situated on Delta Company's lines, earned a Silver Star for suppressing an intense NVA assault in his sector. After expending his M60 ammunition, Parish resorted to his .45 sidearm to repel NVA forces that advanced within 20 yards (18 m) of his foxhole. After the battle, over 100 dead North Vietnamese troops were discovered around Spec. Parish's position.

As the battle along the southern line intensified, Lieutenant Charlie W. Hastings (U.S Air Force liaison forward air controller), was instructed by Lt. Col. Moore (based on criteria established by the Air Force.) to transmit the code phrase "Broken Arrow", which relayed that an American combat unit was in danger of being overrun. In so doing, Lt. Hastings was calling on all available support aircraft in South Vietnam to come to the 1st Battalion, 7th Cavalry's defense, drawing on a significant arsenal of heavy ordnance support. On Charlie Company's broken lines, NVA troops walked the lines for several minutes, killing wounded Americans and stripping their bodies of weapons and other items. It was around this time, at 07:55, that Lt. Col. Moore ordered his lines to throw colored smoke grenades over the lines to identify his battalion's perimeter. Aerial fire support was then called in on the NVA at close range – including those along Charlie Company's lines. Shortly after, Lt. Col. Moore's command post was subjected to a friendly fire incident. Two F-100 Super Sabre jets approached LZ X-Ray to drop napalm inadvertently on American lines. Seeing the approaching F-100's about to drop their bombs dangerously close on the American positions, Lt. Hastings frantically radioed for the two American jets to abort the attack and change course. The pilot of the second approaching F-100 complied and disengaged, but the ordnance from the first F-100 had already been dropped. Despite Lt. Hastings' best efforts, several American soldiers were wounded and killed by this air strike.[37] News reporter Joe Galloway who helped carry one of the badly wounded men (who died two days later) to an aid station, tried to attach a name to the death occurring around him, discovering that this particular soldier's name was Pfc. Jimmy Nakayama of Rigby, Idaho who had been a second lieutenant in the National Guard. Galloway would later share how that same week Nakayama became a father. Galloway also noted "[a]t LZ XRay 80 men died and 124 were wounded, many of them terribly," and that the death toll for the entire battle was 234 Americans killed and perhaps as many as 2,000 North Vietnamese soldiers.[38][39]

At 09:10, the first elements of Alpha Company (2/7), under Captain Joel Sugdinis, arrived at X-Ray. Capt. Sugdinis's forces reinforced the remains of Charlie Company's (1/7) lines. By 10:00, the North Vietnamese had begun to withdraw from the battle – although occasional fire continued to harass the battalion. Charlie Company, having inflicted scores of losses on the NVA, had suffered 42 killed in action (KIA) and 20 wounded in action (WIA) over the course of the two-and-a-half-hour assault. Lieutenant Rick Rescorla a platoon leader of Capt. Diduryk's Bravo Company (2/7) later remarked after having policed up the battlefield in Charlie Company's sector following the assaults: "There were American and NVA bodies everywhere. My area was where Lieutenant Geoghegan's platoon (2nd Platoon, C Company) had been. There were several dead NVA around his platoon command post. One dead trooper was locked in contact with a dead NVA, hands around the enemy's throat. There were two troopers – one black, one Hispanic – linked tight together. It looked like they had died trying to help each other."[35]:215

At 09:30, Colonel Brown, the commander of the 3rd Brigade, 1st Cavalry Division (Airmobile), landed down at LZ X-Ray to make preparation to withdraw the 1st Battalion, 7th Cavalry, deeming its job of drawing the attention of the enemy away from attacking the Pleime camp[34] done.[40]

Reinforcements

Given the tempo of combat at LZ X-Ray and the losses being suffered, other units of the 1st Cavalry Division (Airmobile) planned to land nearby and then move overland to X-Ray. The 2nd Battalion, 5th Cavalry (2/5), was to be flown into LZ Victor, about 3.5 kilometers east-southeast of LZ X-Ray. 2/5 flew in at 08:00 and quickly organized to move out, the trip taking about 4 hours. Most of this was uneventful until they were approaching X-Ray. At about 10:00, some 800 yards (730 m) to the east of the LZ, Alpha Company (2/7) received some light fire and had to set up a combat front. At 12:05, Lt. Col Tully's 2/5 troopers had arrived at the LZ.

Because the 2nd Battalion, 5th Cavalry stealthily closed in the battlefield by foot instead of by heli-lift, B3 Field Front was unaware that the opponent troop ratio had switched from 2:2 to 3:2.[41]

Third push to the lost platoon

Using a plan devised by Lt. Col. Moore, Lt. Col. Tully (2/5) commanded B/1/7, A/2/5, and C/2/5 in a third major effort to relieve the lost B Company platoon of 1/7 under Sgt. Ernie Savage. Making use of fire support, the relief force slowly but successfully made its way to the knoll without encountering NVA elements. 2nd Platoon, B Company had survived but at a significant cost; out of the 29 men, 9 were KIA and 13 WIA. At around 15:30, the relief force began to encounter sniper fire and began the process of carrying the wounded and dead of the lost platoon back to X-Ray. The expanded force at X-Ray, consisting of Moore's weakened 1/7, one company of 2/7, and Tully's 2/5, consolidated at X-Ray for the night. At the LZ, the wounded and dead were evacuated, and the remaining American forces dug in and fortified their lines.

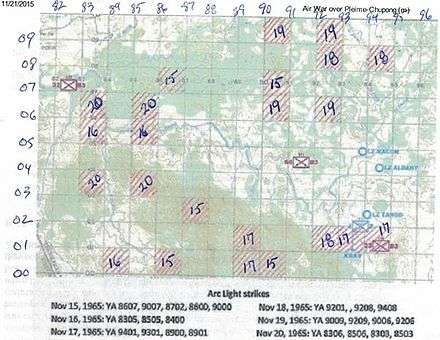

At precisely 16:00, first wave of B-52 carpet bombings fell at YA 8702 (about 7 kilometers west of LZ X-Ray) and would carry on for 5 consecutive days.[42]

At 16:30, Brigadier General Knowles, 1st Cavalry Division (Airmobile) Forward CP Commander, landed down at the LZ X-Ray to announce the withdrawal of the 1st Battalion, 7th Cavalry set for the next day.[43]

Day 3: Nov. 16

While the American lines at X-Ray were harassed at various times during the night of 15 November by NVA probes, it was shortly before 04:00 of the third day that grenade booby traps and trip flares set by Captain Diduryk's Bravo Company (1/7) began to erupt. At 04:22, the NVA launched a fierce assault against Diduryk's men. Bravo fought off this attack by an estimated 300 NVA in minutes. A decisive factor in this stand, in addition to rifle and machine gun fire from B Company's lines, was the skilled placement of artillery strikes by Diduryk's forward observer, Lieutenant Bill Lund. Making use of four different artillery batteries, Lund organized fire into separate concentrations along the battlefield, with devastating consequences for the waves of advancing NVA.

The NVA repeated their assault on Diduryk's lines some 20 minutes after the first attack, as flares dropped from American C-123 Provider aircraft flying above illuminated the battlefield to B Company's advantage. For around 30 minutes, B Company fought off the NVA advance with a combination of small arms and LT. Lund's skilled organization of artillery strikes. Shortly after 05:00, a third attack was launched against B Company, which was repelled by Lieutenant James Lane's platoon within 30 minutes. At almost 06:30, the NVA launched a fourth attack on Diduryk's men – this time in the vicinity of B Company's command post. Again, Lt. Lund's precision in ordering artillery strikes cut down scores of NVA soldiers, while Diduryk's men repelled those who survived using rifle and machine gun fire. At the end of these attacks, with daybreak approaching, Diduryk's Company had only six lightly wounded men among its ranks – with none killed.

LZ X-Ray secured

Around 10:30 a.m., 1st Battalion, 7th Cavalry received order to withdraw from the battle zone while 2nd Battalion, 7th Cavalry and 2nd Battalion, 5th Cavalry took up defensive positions for the night. The intention was to reassure the NVA side in seeing that the opponent troop ratio has been reverting to 2:2.

According to the assessment of ARVN General Nguyen Vinh Loc, at the LZ X-Ray battle, the NVA did not have anti-aircraft weapons and heavy mortars and had to resort to "human wave" tactic: "The enemy has lost nearly all their heavy crew-served weapons during the first phase ... Their tactics relied mostly on the 'human waves'".[44]

The battle was ostensibly over. The NVA forces had suffered hundreds of casualties and were no longer capable of a fight. U.S. forces had suffered 79 killed and 121 wounded and had been reinforced to levels that would guarantee their safety. Given the situation there was no reason for the U.S. forces to stay in the field, their mission was complete and arguably a success. Moreover, Col. Brown (3rd Brigade commander), in overall command, was worried about reports that additional NVA units were moving into the area over the border. He wanted to withdraw the units, but General Westmoreland demanded that the 2/7 and 2/5 stay at X-Ray to avoid the appearance of a retreat.

Just after the withdrawal of the 1st Battalion, 7th Cavalry, a B-52 strike was conducted over the battalions abandoned positions in LZ X-Ray.[45]

The U.S. reported the bodies of 634 NVA soldiers were found in the vicinity. The U.S. estimated that 1,215 NVA were killed a distance away by artillery and airstrikes. Six North Vietnamese soldiers were captured.[46] Six PAVN crew-served weapons and 135 individual weapons were captured, and an estimated 75–100 weapons were destroyed.[8] The normal ratio of enemy soldiers killed to weapons captured as later established by the Department of Defense was 3 or 4 to one.[47]

LZ Albany

Day 4: Nov. 17

The next day, the two remaining battalions abandoned LZ X-Ray and began a tactical march to new landing zones. Lt. Col. Bob Tully, commanding the 2nd Battalion, 5th Cavalry, went to LZ Columbus about 4 km (2 mi) to the northeast, and Lt. Col. Robert McDade, commanding the 2nd Battalion, 7th Cavalry, went to LZ Albany about 4 km (2 mi) to the north-northeast, close to the Ia Drang. Tully's men moved out at 09:00; McDade's followed ten minutes later.[35] U.S. Air Force B-52 Stratofortresses were on their way from Guam, and their target for the third day of bombing was the slopes of the Chu Pong massif and LZ X-Ray itself. The U.S. ground forces had to move outside a two-mile (3 km) safety zone by midmorning to be clear of the bombardment.[48]

Events leading to an ambush

The first indication of enemy presence was observed by the reconnaissance platoon's point squad which was leading the American column. Staff Sergeant Donald J. Slovak, the squad's leader, saw "Ho Chi Minh sandal foot markings, bamboo arrows on the ground pointing north, matted grass and grains of rice."[35]:285,286 After marching about 2,000 meters, Alpha Company (1/7) leading 2/7, headed northwest, while 2/5 continued on to LZ Columbus. Alpha Company came upon some grass huts which they were directed to burn. At 11:38, Lt. Col. Tully's men of 2/5, were logged into its objective, LZ Columbus. Communist troops in the area consisted of the NVA's 8th Battalion, 66th Regiment, 1st Battalion, 33rd Regiment, and the headquarters of the 3rd Battalion, 33rd Regiment . While the 33rd Regiment's battalions were under strength from casualties incurred during the battle at the Army Special Forces Plei Me camp, the 8th Battalion was General Chu Huy Man's reserve battalion, fresh and rested.[35]:288

Alpha Company soon noticed the sudden absence of air cover and their commander, Captain Joel Sugdinis, wondered where the aerial rocket artillery choppers were. He soon heard the sound of distant explosions to his rear; the B-52's were making their bombing runs on the Chu Pong massif. Lieutenant D. P. (Pat) Payne, the recon platoon leader, was walking around some termite hills when he suddenly came upon a North Vietnamese soldier resting on the ground. Payne jumped on the NVA trooper and took him prisoner. Simultaneously, about ten yards away, his platoon sergeant captured a second NAV soldier. Other members of the NVA recon team may have escaped and reported to the headquarters of the 1st Battalion, 33rd Regiment. The NVA then began to organize an assault on the American column. As word of the capture reached him, Lt. Col. McDade ordered a halt as he went forward from the rear of the column to interrogate the prisoners personally. The two captured NVA soldiers were policed up about a hundred yards from the southwestern edge of the clearing called Albany, the report of which reached division forward at Pleiku at 11:57.[35]:289,290

Lt. Col. McDade then called his company commanders of 2/7 forward for a conference; most of whom were accompanied by their radio operators. Alpha Company moved forward to LZ Albany; McDade and his command group were with them. Following orders, the other company commanders were moving forward to join Lt. Col. McDade. Delta Company, which was next in the column following Alpha Company, was holding in place; so was Charlie Company which was next in line. Second Battalion Headquarters Company followed, and Alpha Company, 1/5, brought up the rear of the column. The American column was halted in unprepared, open terrain, and strung out in 550-yard (500 m) line of march.[35]:292,293 Most of the units had flank security posted, but the men were worn out from almost sixty hours without sleep and four hours of marching. The elephant grass was chest-high so visibility was limited. The column's radios for air or artillery support were with the company commanders.

An hour and ten minutes after the NVA recon soldiers were captured, Alpha Company and Lt. Col. McDade's command group had reached the Albany clearing. McDade and his group walked across the clearing and into a clump of trees. Beyond that clump of trees was another clearing. The remainder of the battalion was in a dispersed column to the east of the LZ. Battalion Sergeant Major James Scott and Sergeant Charles Bass then attempted to question the prisoners again. While they were doing this, Bass heard Vietnamese voices, and the interpreter confirmed that these were NVA talking. Alpha Company had been in the LZ about five minutes. Right about then, small arms fire erupted.

2nd Battalion ambushed

Lt. Pat Payne's reconnaissance platoon had walked to within 200 yards (180 m) of the headquarters of the NVA's 3rd Battalion, 33rd Regiment; the 550-man strong 8th Battalion, 66th Regiment had been bivouacked off to the northeast of the American column. As the Americans rested in the tall grass, North Vietnamese soldiers were coming towards them by the hundreds. It was 13:15. The close quarters, intense battle lasted for sixteen hours.[35]:293–295

North Vietnamese forces first struck at the head of 2nd Battalion, 7th Cavalry's column and rapidly spread down the right or east side of the column in an L-shaped ambush.[49] NVA troops ran down the length of the column, with units peeling off to attack the outnumbered American soldiers, engaging in intense, brutal close-range and hand-to-hand combat. McDade's command group made it into the clump of trees between the two clearings that constituted LZ Albany. They took cover from rifle and mortar fire within the trees and termite hills. The reconnaissance platoon and 1st Platoon, Alpha Company, provided initial defense at the position. By 13:26, they had been cut off from the rest of the column; the area whence they had come was swarming with NVA soldiers. While they waited for air support, the Americans holding LZ Albany drove off any NVA assaults on them and sniped at the exposed enemy wandering around the perimeter. It was later discovered that the NVA were mopping up, looking for wounded American soldiers in the tall grass and killing them.[35]:300–305

All the while the noise of battle could be heard in the woods as the other companies fought for their lives. The 2nd Battalion, 7th Cavalry had been reduced to a small perimeter at Albany composed of survivors of Alpha Company, the recon platoon, survivors from the decimated Charlie and Delta Companies, and the command group. There was also a smaller perimeter at the rear of the column about 500–700 yards due south: Captain George Forrest's Alpha Company, 1st Battalion, 5th Cavalry. Captain Forrest had run a gauntlet all the way from the conference called by Lt. Col. McDade back to his company when the NVA mortars started coming in. Charlie and Alpha companies lost a combined 70 men in the first minutes. Charlie Company suffered 45 dead and more than 50 wounded, the heaviest casualties of any unit that fought on Albany.[35]:309 USAF A-1E Skyraiders soon provided much-needed support, dropping napalm bombs. However, because of the fog of war and the inter-mixing of both American and North Vietnamese troops, it is likely that the air and artillery strikes killed not just NVA soldiers, but American soldiers as well.[49]

American reinforcements arrive

At 14:55, Bravo Company, 1st Battalion, 5th Cavalry under Captain Buse Tully began marching from LZ Columbus to the rear of the 2nd Battalion, 7th Cavalry column that was about two miles (3 km) away. By 16:30, they came into contact with the Alpha Company (1/5) perimeter under Captain Forrest. A one-helicopter landing zone was secured, and the wounded were evacuated. Captain Tully's men in 2/5 then began to push forward towards where the rest of the ambushed column would be. NVA troopers contested their advance, and the Americans came under fire from a wood line. Tully's men assaulted the tree line and drove off the North Vietnamese. At 18:25, orders were received to secure into a two-company perimeter for the night. They planned to resume the advance at daybreak.[35]:339,340

At around 16:00, Captain Myron Diduryk's Bravo Company, 2nd Battalion, 7th Cavalry, veterans of the fight at LZ X-Ray, got the word that they would be deployed in the battalion's relief. At 18:45 the first helicopters swept over the Albany clearing and the troopers deployed into the tall grass.[35]:341–343 Lieutenant Rick Rescorla, the sole remaining platoon leader in Bravo Company, led the reinforcements into the Albany perimeter, which was expanded to provide better security. The wounded at Albany were evacuated at around 22:30 that evening, the helicopters receiving intense ground fire as they landed and took off. The Americans at Albany then settled down for the night.

Day 5: Nov. 18

As Friday, November 18, dawned on the battlefield, the U.S. soldiers began to gather up their dead comrades. This task took the better part of two days, as American and North Vietnamese dead were scattered all over the field of battle. Rescorla described the scene as, "a long, bloody traffic accident in the jungle."[35]:369 While securing the battlefield, Rescorla recovered a large, battered, old French army bugle from a dying NVA soldier. The American soldiers finally left LZ Albany for LZ Crooks at 13°40′5.6″N 107°39′10″E / 13.668222°N 107.65278°E, six miles (10 km) away, on November 19. The battle at LZ Albany cost the United States Army 155 men killed or missing and 124 wounded.[35]:295 One U.S. soldier, Toby Braveboy, was recovered on November 24 when he waved down a passing H-13 scout helicopter.[35]:352–354 In this 16-hour fight, about half of the approximately 300 American deaths occurred in the 35-days of Operation Silver Bayonet.[9]

The United States reported 403 NVA troops were killed in this battle and an estimated 150 were wounded. Weapons captured included 112 rifles, 33 light machine-guns, three heavy machine-guns, two rocket launchers, and four mortars.[50]

Effect and aftermath

The air assault insertion of the 1st Battalion, 7th Cavalry at LZ X-Ray in the morning of November 14 had the effect of making the B3 Field Front to postpone the attack of the Pleime Camp.[34] The B3 Field Front reacted by the NVA committing the 7th and 9th Battalions while the remaining units of its force were put on hold at their staging positions. The 1st Air Cavalry Division reinforced 1/7 with the 2nd Battalion, 7th Cavalry. On November 15, Lt. Col. Moore in command of 1/7 at X-Ray, was ordered to make preparation to withdraw his unit because it had achieved its mission;[40] in the meantime, the 2nd Battalion, 5th Cavalry closed into X-Ray by noon to assist in the withdrawal of 1/7 scheduled for November 16. At precisely 1600 hours[51] on November 15, the first waves of B-52's struck the Chu Pong-Ia Drang complex at approximately 7 kilometers west of X-Ray while the NVA's 32nd Regiment held its positions at 12-14 kilometers.[42] In the morning, 1/7 was helicoptered out of LZ X-Ray, covered by 2/7 and 2/5.[52] On November 17, the two remaining battalions also abandoned the landing zone to make way for the B-52 strike that caught any NVA troops at the "now-deserted X-Ray area" by surprise.[45]

As the fight at LZ Albany was coming to an end, the ARVN II Corps Command decided to 'finish off' the campaign by introducing the ARVN Airborne Brigade into the battlefield on November 17 with the establishment of a new artillery support base at LZ Crooks, secured by the 2nd Battalion, 5th Cavalry.[53] The ARVN Airborne Brigade executed two ambushes: the first on November 20 at the north side and the second on November 24 on the south side of the la Drang river.[54] On November 24, witnessing no further contact, the ARVN withdrew from the area.[55]

A 1966 NVA Central Highlands Front report claimed that in five major engagements with U.S. forces, NVA forces suffered 559 soldiers killed and 669 wounded. NVA histories claim the United States suffered 1,500 to 1,700 casualties during the Ia Drang Campaign. The U.S. military confirmed 305 killed and 524 wounded (including 234 killed and 242 wounded between November 14 and 18, 1965), and claimed 3,561 NVA were killed and more than 1,000 were wounded during engagements with the 1st Cavalry Division troops.[56]

According to ARVN intelligence source, each of the three NVA regiments' initial strength was 2,200 soldiers:[7] 1st Battalion-500, 2nd Battalion-500, 3rd Battalion-500, Mortar Company-150, Anti-Aircraft Company-150, Signal Company-120, Transportation Company-150, Medical Company-40, Engineer Company-60, Recon Company-50. On November 17, after 3 days of the B-52 airstrike, ARVN intelligence source through radio intercepts revealed that B3 Field Front Command reported "2/3 of their strength had been wiped off",[53] or 6 out of 9 battalions; still combat effective were the 635th and 334th Battalions of the 320th Regiments[57] and the 5 companies of the remnant 33rd and 66th Regiments that were to be decimated at the battle of LZ Albany. As a matter of fact, when the ARVN Airborne, comprizing 5 battalions, entered into action, they only encountered two NVA battalions.[26]

ARVN's II Corps Command recapitulates the losses of the NVA from 18 October to 26 November as follows:[56] KIA (bc) 4,254, KIA (est) 2,270, WIA 1293, CIA 179, weapons (crew served) 169, (individual) 1,027. NVA casualty figures advanced by II Corps Command were relied especially on NVA regimental command posts' own loss reports (as indicated by Major General Kinnard),[58] intercepted by ARVN radio listening stations.[59] Furthermore, they include NVA troop casualties caused by the 5 day Arc Light airstrike that the NVA and U.S. sides fail to take into account.

As the outcome of the entire campaign, the ARVN claimed that the NVA were unable to achieve their objectives of overrunning the camp and destroying the relief column at Pleime, as well as that the entire B3 Field Force strength had been wiped out and the survivors pushed over the Cambodian border.[60]

Both sides (U.S. and North Vietnam) probably inflated the estimates of their opponent's casualties.[13] Lewy states that, according to DOD officials, US "body count" claims of communist casualties were inflated at least 30 percent for the Vietnam War as a whole. The U.S. claim of 403 North Vietnamese battle dead at Landing Zone Albany seems an overestimate. Lt. Col. McDade (2/7) later claimed he did not report any estimate of North Vietnamese casualties at LZ Albany and had not seen even 200 bodies of North Vietnamese soldiers.[14] Similarly, Lt. Col. Moore also acknowledged that the NVA casualty figures in the fight at LZ X-Ray were inaccurate. He lowered the original body count figure of 834 submitted by his men to 634, regarding the former number was too high.[15]

This battle can be seen as a blueprint for tactics by both sides. The Americans used air mobility, artillery fire and close air support to accomplish battlefield objectives. The NVA learned that they could neutralize that firepower by quickly engaging American forces at very close range. North Vietnamese Colonel Nguyen Huu An included his lessons from the battle at X-ray in his orders for Albany, "Move inside the column, grab them by the belt, and thus avoid casualties from the artillery and air."[61] Both Westmoreland and An thought this battle to be a success. This battle was one of the few set piece battles of the war and was one of the first battles to popularize the U.S. concept of the "body count" as a measure of success, as the U.S. claimed that the kill ratio was nearly 10 to 1.[44]

In the late 1940s, General Vo Nguyen Giap wrote about the Viet Minh war against the French: "The enemy will pass slowly from the offensive to the defensive. The blitzkrieg will transform itself into a war of long duration. Thus, the enemy will be caught in a dilemma: He has to drag out the war in order to win it and does not possess, on the other hand, the psychological and political means to fight a long-drawn-out war." After this battle, he said: "We thought that the Americans must have a strategy. We did. We had a strategy of people's war. You had tactics, and it takes very decisive tactics to win a strategic victory... If we could defeat your tactics — your helicopters — then we could defeat your strategy. Our goal was to win the war." [11]

Commenting later on the battle, Harold (Hal) G. Moore said, The "peasant soldiers [of North Vietnam] had withstood the terrible high-tech fire storm delivered against them by a superpower and had at least fought the Americans to a draw. By their yardstick, a draw against such a powerful opponent was the equivalent of a victory."[62]

Casualty notification

The U.S. Army had not yet set up casualty-notification teams this early in the war. The notification telegrams at this time were handed over to taxi cab drivers for delivery to the next of kin. Hal Moore's wife, Julia Compton Moore, followed in the wake of the deliveries to widows in the Ft. Benning housing complex, grieving with the wives and comforting the children, and attended the funerals of all the men killed under her husband's command who were buried at Fort Benning.[49] Her complaints about the notifications prompted the Army to quickly set up two-man teams to deliver them, consisting of an officer and a chaplain.[63] Mrs. Frank Henry, the wife of the battalion executive officer, and Mrs. James Scott, wife of the battalion command sergeant major, performed the same duty for the dead of the 2nd Battalion, 7th Cavalry.[35]:416

Notable award recipients

Although many notable decorations have been awarded to veterans of the Battle of Ia Drang, in his book We Were Soldiers Once...And Young, Lieutenant General Harold Moore writes:

"We had problems on the awards... Too many men had died bravely and heroically, while the men who had witnessed their deeds had also been killed... Acts of valor that, on other fields, on other days, would have been rewarded with the Medal of Honor or Distinguished Service Cross or a Silver Star were recognized only with a telegram saying, 'The Secretary of the Army regrets...' The same was true of our sister battalion, the 2nd of the 7th." [61]

- Medal of Honor

- Second Lieutenant Walter Marm, Company A, 1st Battalion, 7th Cavalry, received the Medal of Honor on February 15, 1967, for his actions while serving as a platoon leader on 14 February during the 3-day battle at LZ X-Ray. His MOH citation recounts several examples of conspicuous gallantry, some despite being severely wounded.[64]

- Captain Ed Freeman and Major Bruce Crandall who were helicopter pilots during the battle were each awarded the Medal of Honor on July 16, 2001 and February 26, 2007, respectively, for their numerous volunteer flights (14 and 22, respectively) in their unarmed Hueys[65] into LZ X-Ray while enemy fire was so heavy that medical evacuation helicopters refused to approach. With each flight, Crandall and Freeman delivered much needed water and ammunition and extracted wounded soldiers, saving countless lives.[66]

- Distinguished Service Cross, Silver Star, and Bronze Star Medal

- Lieutenant Colonel Harold "Hal" Moore, commanding officer of the 1st Battalion, 7th Cavalry Regiment was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross for his actions at LZ X-Ray. His DSC citation particularly commends his "leadership by example" as well as his skill in battle against overwhelming odds and his unwavering courage.[67]

- Sergeant Ernie Savage's precise placement of artillery throughout the siege of the "Lost Platoon" enabled the platoon to survive the long ordeal. For his "gallantry under relentless enemy fire on an otherwise insignificant knoll in the valley of the Ia Drang," Ernie Savage received the Distinguished Service Cross.[68]

- Second Lieutenant John Geoghegan was posthumously awarded the Silver Star, Bronze Star, Purple Heart, and the Air Medal. He was killed during the battle when he rushed to the aid of fellow soldier, Willie Godbolt, who was wounded by incoming hostile fire. Their names are next to each other on the Vietnam Wall.[69]

- Journalist Joseph Galloway was the only civilian awarded the Bronze Star Medal for heroism during the Vietnam War. On November 15, 1965, he disregarded his own safety to help rescue two wounded soldiers while under fire.[70][71]

- Presidential Unit Citation

- The 1st Cavalry Division (Airmobile) And Attached Units: Presidential Unit Citation, DAGO 40, 1967: 23 October to 26 November 1965: Distinguished themselves by outstanding performance of duty and extraordinary heroism against an armed enemy in the Republic of Vietnam, becoming the first unit so honored for actions during the Vietnam War.[72]

In media

Films

- The short film The Battle of Ia Drang Valley (1965) is available for free download at the Internet Archive

- We Were Soldiers (2002), war film based on Moore and Galloway's book

Literature

- Alley, J. L. Bud (1Lt) (2016). The Ghosts of the Green Grass., an account of the ambush of 2nd battalion at LZ Albany

- Mason, Robert (Vietnam War helicopter pilot) (1983). Chickenhawk.

- Moore, Harold G. (Ret. Lt. Gen.) Galloway, Joseph L. (war journalist) (1992). We Were Soldiers Once... And Young.

- Terry, Wallace (1984). Bloods: An Oral History of the Vietnam War by Black Veterans. Random House. ISBN 0394530284. (ISBN 978-0-394-53028-4), a book which includes accounts by multiple soldiers who recounted the Battle of Ia Drang

Television

- Vietnam in HD (November 8 to November 11, 2011), a 6-part American documentary television miniseries on The History Channel that covered the Battle of la Drang in its first episode

Notes

- Citations

- ↑ Vinh Loc, page 78

- ↑ Vinh Loc, page 119.

- 1 2 Stanton, Vietnam Order of Battle, page 73

- 1 2 3 4 5 http://www.ordersofbattle.darkscape.net/site/history/open3/us_iadrang1965.pdf

- 1 2 3 Kinnard, page i

- ↑ Kennedy Hickman. "Vietnam War – Battle of Ia Drang (1965)". About.com Education.

- 1 2 Vinh Loc, page 112

- 1 2 3 "Colonel Hieu and LTC Hal Moore re: LZ X-Ray After Action Report (m)". generalhieu.com.

- 1 2 Herbert C Banks, 1st Cavalry Division: A Spur Ride Through the 20th Century "From Horses to the Digital Battlefield", Turner Publishing Company, 2003

- 1 2 3 4 5 Pribbenow, Merle L. "The Fog of War: The Vietnamese View of the Ia Drang Battle". generalhieu.com. Retrieved April 9, 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Joseph Galloway. "Ia Drang – The Battle That Convinced Ho Chi Minh He Could Win". Historynet. Retrieved May 2, 2016.

- ↑ Mark W. Woodruff, Unheralded Victory: The defeat of the Viet Cong and the North Vietnamese Army, 1961–1973, Vandamere Press, 1999

- 1 2 Lewy, Gunther (1978), America in Vietnam, New York: Oxford University Press, page 450

- 1 2 Carland, page 145

- 1 2 Carland, page 150

- ↑ Vinh Loc, page 82

- ↑ Coleman, page 270

- ↑ Vietnam War, 1961–1975, Wilson Center

- ↑ Vĩnh Lộc, page 124

- ↑ General Nguyen Nam Khanh, Quan Doi Nhan Dan magazine, November 13, 2005

- ↑ Nguyen Huy Toan and Pham Quang Dinh, 304th Division, volume II, page 19

- ↑ Kinnard, page 82: "Field Front forces began staging in the Chu Pong-Ia Drang area in preparation for movement to Pleime"

- ↑ McChristian, page 6

- ↑ Vinh Loc, page 49

- ↑ G3Journal/I Field Force Vietnam

- 1 2 Vĩnh Lộc, page 101

- ↑ Kinnard, page 1

- ↑ Kinnard, page 67

- ↑ Kinnard, page 73

- ↑ Kinnard, page 76

- ↑ McChristian, page 44

- ↑ Coleman, page 196

- ↑ Coleman, page 199

- 1 2 3 Nguyễn Hữu An, page 32

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 Moore, Harold G. & Joseph L. Galloway (1992). We Were Soldiers Once... and Young. HarperTorch. pp. 277, 278. ISBN 0-679-41158-5.

- ↑ "Walter Joseph Marm Jr.". mishalov.com.

- ↑ Military and the Media – Speech Prepared for delivery October 22, 1996 at the Air War College Commandant's Lecture Series. Au.af.mil. Retrieved on February 10, 2011

- ↑ Joe Galloway (2002). "A Reporter's Journal From Hell". Digital Journalist. pp. Part 4. Retrieved June 17, 2013.

- ↑ Lorna Thackeray (March 30, 2002). "The valley of death". Billings Gazette. Retrieved June 18, 2013.

- 1 2 Moore, page 202

- ↑ Nguyễn Hữn An, page 37

- 1 2 Kinnard, page 88

- ↑ Moore, page 210

- 1 2 Vinh Loc, page 90

- 1 2 Kinnard, page 94

- ↑ Woodruff, Mark (1999). Unheralded Victory: Who Won the Vietnam War?. London: Harper Collins. p. 81. ISBN 0004725409.

- ↑ Lewy, Guenter (1978), America in Vietnam, New York: Oxford University Press pages 54-55, 142; "1st Cavalry Division Association - Interim Report of Operations", First Cavalry Division, July 1965 to December 1966", ca. 1967, Folder 01, Box 01, Richard P. Carmody Collection, The Vietnam Center and Archive, Texas Tech University. Accessed April 17, 2015. <http://www.vietnam.ttu.edu/virtualarchive/items.php?item=22030101001>accessed April 16, 2015

- ↑ G3 Journal/MACV, 11/17 entry

- 1 2 3 Galloway, Joseph L. (October 29, 1990). "Vietnam story: The word was the Ia Drang would be a walk. The word was wrong.". U.S. News & World Report. Archived from the original on September 11, 2002. Retrieved May 7, 2007.

- ↑ Woodruff, Mark (1999). Unheralded Victory: Who Won the Vietnam War?. London: Harper Collins. p. 83. ISBN 0004725409.

- ↑ G3 Journal/IFFV, 11/15 entry

- ↑ Moore, page 229

- 1 2 Vinh Loc, page 97

- ↑ Vinh Loc, page 101-103

- ↑ Vĩnh Lộc, page 132

- 1 2 Vinh Loc, page 111

- ↑ Pribblenow, The Fog of War, footnote 53 citing The Pleime Offensive

- ↑ Kinnard, page 70

- ↑ McChristian, page 41; Vinh Loc, page 97 and 111

- ↑ Vinh Loc, page 103

- 1 2 Harold G. Moore; Joseph L. Galloway (1992). We Were Soldiers Once ... and Young — Ia Drang: the battle that changed the war in Vietnam. Random House. ISBN 0-679-41158-5. Retrieved February 10, 2011.

- ↑ Moore, Jr., Harald G. and Galloway, Joseph L. (1992), We Were Soldiers Once...and Young, New York: Ballantine Books, page 368

- ↑ Galloway, Joseph L. (April 21, 2004). "Rest in peace, Julie Moore.". obit. Knight-Ridder/Tribune News Service. Retrieved April 29, 2007.Courtesy link to full text.

- ↑ "Medal of Honor Recipients Full-Text Citations – Vietnam (M–Z)". United States Army Center of Military History. Archived from the original on November 12, 2010. Retrieved December 4, 2010.

- ↑ "Medal of Honor, Vietnam War – Major Bruce P. Crandall". Biography. United States Army Center of Military History. July 20, 2009. Archived from the original on February 6, 2010. Retrieved February 15, 2010.

- ↑ "Medal of Honor Recipients Full-Text Citations – Vietnam (A–L)". United States Army Center of Military History. Archived from the original on October 10, 2009. Retrieved September 21, 2009.

- ↑ "Valor awards for Harold Gregory Moore, Jr.". MilitaryTimes.com. Retrieved February 10, 2011.

- ↑ Leonard, Steven M. (March–April 2006). "Forward Support in the Ia Drang Valley". Army Logistician. 38 (2). Archived from the original on July 16, 2011. Retrieved July 18, 2011.

- ↑ "Virtual Wall for John Lance Geoghegan". virtualwall.org. Retrieved May 22, 2015.

- ↑ "Joseph L. Galloway Biography", We Were Soldiers, Open Road Integrated Media

- ↑ We Were Soldiers, BSM Citation

- ↑ http://www.first-team.us/tableaux/apndx_07/

References used

- Carland, John M. (2000). Combat Operations: Stemming the Tide, May 1965 to October 1966. Government Printing Office. ISBN 9780160873102.

- Cash, John A.; Albright, John; Sandstrum, Allan W. (1985) [1970]. "Fight at Ia Drang". Seven Firefights in Vietnam. Washington, D.C.: The United States Army Center of Military History.* Coleman, J.D. (1988). Pleiku, The Dawn of Helicopter Warfare in Vietnam. New York: St.Martin's Press.

- G3 Journal/I Field Force Vietnam, November 14–26, 1965 , , , document stored at the National Archive, College Park, Maryland.

- Head, William (2014). A Re-assessment of the Battle of Ia Drang Valley, 1965: The Role of Airpower, Heroic Soldiers and the Wrong Lessons. Virginia Review of Asian Studies, Volume 16. pp. 27–55.

- Kinnard, William (1966). Pleiku Campaign, After Action Report.

- McChristian, J.A. (1966). Intelligence Aspects of Pleime/Chupong Campaign, J2/MACV.

- Melyan, Wesley R.C. (15 September 1967). Arc Light 1965-1966. HQ PACAF: Checo project, Tactical Evaluation Center.

- Moore, Harold G.; Galloway, Joseph L. (1992). We Were Soldiers Once ... and Young — Ia Drang: the battle that changed the war in Vietnam. New York, New York: Harper Perennial. ISBN 0-06-097576-8.

- Nguyễn Hữu An (2005). Chiến Trường Mới, Hồi Ức. Hà Nội: Nhà xuất bản Quân đội Nhân dân.

- Porter, Melvin F. (February 24, 1966). The Siege of Pleime. HQ PACAF: CheCo project,Tactical Evaluation Center.

- Porter, Melvin F. (February 26, 1966). Silver Bayonet. HQ PACAF: CheCo project,Tactical Evaluation Center.

- Vĩnh Lộc (1966). Pleime Trận Chiến Lịch Sử. Viet Nam: Bộ Thông Tin.

- Vinh Loc (1966). Why Pleime. Viet Nam: Information Printing Office.

- Westmoreland, William, General Westmoreland's History Notes (29 August-29 November 1965) , unpublished MACV files.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Battle of Ia Drang. |

- LZ X-Ray

- Jack Smith's account of the battle

- Smith, Jack P. (November 17, 1998). "Death in the Ia Drang Valley". Neil Mishalov. Retrieved July 28, 2009.