Battle of Hyderabad

| Battle of Hyderabad | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the conquest of Sindh | |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Great Britain | Talpur Emirs of Sindh | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Captain James Outram Sir Charles Napier[1] |

Mir Sher Muhammad Talpur Hoshu Sheedi † | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

Native Infantry Native Cavalry Scinde Horse 1st Troop Bombay Horse Artillery Cheshire Regiment 15,000 men | 20,000 Baloch | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 1000 | 2,000[2] | ||||||

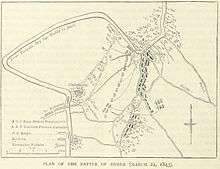

The Battle of Hyderabad, also called The Battle of Dubba (or The Battle of Dubbo in contemporary references)[3] was fought on 24 March 1843 between the British colonial empire and the Talpur Emirs of Sindh near Hyderabad, Sindh, Pakistan. A small British force, led by Captain James Outram, were attacked by the Talpur Balochis and forced to make a fort of the British residence, which they successfully defended until they finally escaped to a waiting river steamer. After the British victory at Meeanee (also spelt Miani), Sir Charles Napier continued his advance to the Indus River and attacked the Sindh capital of Hyderabad. Hyderabad was defended by 20,000 troops under the command of Mir Sher Muhammad Talpur and Hosh Mohammad. Charles Napier with a force of only 6,000 men but with artillery support stormed the city. During the battle Hosh Mohammad was killed and his forces routed; Baluchistani resistance collapsed and Sindh came under British rule.

Prelude

The British became involved in the region of Sindh in Pakistan (at that time India), under the authority of Lord Ellenborough. In 1809, The Amirs of Sindh signed a treaty of "perpetual friendship" with the British,who established a local representative in the city of Hyderabad. With this arrival of British influence within the region, the Amirs of the Sindh lessened their internal struggles and turned instead to face this foreign presence.[4] In 1838, the British representative had the Amirs sign a political residency treaty, allowing a British residency in the city of Hyderabad, which paved the way for further British involvement in the area. This same treaty also stipulated that the British would fix the differences held between the rulers of the Sindh and those of the Punjab.[5] Soon after, this would be taken a step further in the signing of a treaty pushed by the British that would allow British troops to be stationed permanently in the Sindh region for ‘the protection of the Amirs’. The Amirs would also have to pay for a British resident in Hyderabad, who would negotiate all relations between the British and the Amirs.[6]

The British maintained various policies among the different Amirs, so as to please each individual and divide them by dealing with them separately.[5] Captain James Outram was initially in charge of these dealings, and he made significant progress with the Amirs, who began confiding in him. As a result, Outram was able to attain power over the Amirs’ foreign policy as well as to station his troops in the province.[5] Tensions began to rise when the British, who were involved in the politics in Afghanistan at the time, started interfering in the internal affairs of the Amirs as well as asking them for land which the British desired. The British were supporting Shah Shujah Durrani to take the throne in Afghanistan.[7] The Amirs, however, resented this proposal, which added to their discontentment with the British occupations. The Amirs refused to aid Shah Shujah in Afghanistan and, siding more with the Shah of Persia, angered the British.[8]

These relations took a turn for the worse when allegations were made of the Amirs communicating with the Shah of Persia, a rival of Shah Shujah and the British. It was after this incident that the British made it clear to the Amirs of the Sindh that any further cooperation with any people other than the British would lead to their destruction and their loss of rule in the Sindh.[7] The distrust between the British and the Amirs of the Sindh continued to worsen, as both sides grew more and more suspicious of each other. Both sides continued on, feigning normality while both were aware of the other’s mistrust.[9] As a result of their distrust, the British began to keep a close eye on Noor Mohammed Khan, one of the most prominent Amirs, at his residence in Hyderabad.[10]

In 1841, the British appointed Charles Napier for service in India at the age of 59. The following year Napier arrived in Bombay on 26 August. Upon his arrival he was told of the situation that existed between the British and the Amirs, and that the Amirs were making trouble for the British. On 10 September 1842 Napier arrived in the Sindh.[11] Under Napier, British control saw some charity on their occupation of Sindh and the territory of the Amirs. There was a belief that the British were, in fact, improving life for many in the area, as they saw the Amirs as overly wealthy rulers over a poor people.[12] Napier was also very much of a mind to expand and tighten British control. Previously Outram had been in charge of negotiations between the British and the Amirs and had been very lenient towards the Amirs, which they appreciated greatly. Napier, on the other hand, not only longed for campaign, but was also very authoritarian with regard to the British rule in the area, and wanted to see full control by the British.[13] Napier himself was charged by Ellenborough to look into the matter of the Amirs’ duplicity, to find evidence of their suspicious behaviour, and to compile it into a report which he would submit to Ellenborough.[14] However, due to the fact that Napier was fresh to the Sindh and knew none of the language which would allow him to understand the pieces of alleged evidence against the Amirs, he was left with a difficult task.[15]

Napier’s 200-page report was submitted to Ellenborough, who received the it on November 3. The report was fairly inaccurate in its information about the Amirs, and Ellenborough sent his reply the day after as well as draft of a new treaty to be made with the Amirs.[16] The speed of the reply, as well as the fact that it was accompanied by a drafted treaty, would indicate that Ellenborough had made his decision and the draft even before receiving Napier’s report.[17] Ellenborough’s reply urged Napier to find convicting evidence of the actions of the Amirs - of which he had fairly little. His most incriminating piece of evidence was a letter supposedly written by the Amir, but which might easily have been a forgery, of which Napier was aware. As a result, Napier wrote to Ellenborough again, telling him of the small pieces of evidence that he had and asked for Ellenborough’s help in the situation. However, Ellenborough replied saying that he agreed with the verdict made by Napier - though he had not concretely stated one.[18]

Conflict

In February 1843, Amir Sodbar resided at Hyderabad Fort. While Sodbar was cooperative with the British, Napier was wary of him, and felt Sodbar was too much of a liability for the British, though the Amir was unaware of these feelings.[19] As a result, when Napier asked Sodbar to send away Balochi troops from the Fort, Amir Sodbar complied. Napier then took control of the fort himself, raising the British flag and stationing troops there.[19] At first Napier was hesitant to hold Sodbar prisoner. However, after some of Sodbar’s men resisted the British, against Sodbar’s will, Napier decided to hold the Amir as a prisoner in Hyderabad Fort.[20] Ellenborough gave orders for all treasure and articles of wealth to be seized from the Amir’s residence in Hyderabad, except that which the women chose to retain as their own jewelry or possessions. Collection agents were appointed to mediate the confiscation of the wealth. Some of the women made good use of this opportunity to take large amounts of wealth with them, while others, fearful of the British appointees, gave up much of their possessions.[21] Around this time, Napier heard word of one of the Amirs, Sher Mohammad, mustering troops to resist the British forces. Napier was under the impression that Sher Mohammad would offer little resistance as he had very little funds or weapons, and was therefore surprised to hear that he had almost 30,000 troops ready to be brought against the British.[22]

Upon hearing of Sher Mohammad’s foreboding army, Napier immediately sent for reinforcements to be sent from Ferozepur and Sukkur. Around the same time, Balochi soldiers began to attack British supply routes along the Indus as well as those from Karachi to other British holdings.[23] It was Napier’s intent to hold off battle as long as he could so as to get the most reinforcements that he could manage. He was sent a message from Sher Mohammad, promising the safety of Napier and his men if he would give up the fort and the confiscated wealth. In reply, Napier fired cannons from the fort as a sign that he would not surrender.[23]

On 20 March, Sir Charles Napier went out to reconnotire Sher Mohammad’s position near Tando Ali Jam, finding the Amir’s army to be strong and holding excellent territory for defense. The next day, Napier received much needed reinforcements who arrived by ship, coming down the Indus from Sukkur.[24]

Battle

On 24 March 1843 British troops, led by Sir Charles Napier, set out from Hyderabad to meet Sher Mohammad. After marching for some time, the British forces came upon the Amir’s army.[25] While waiting for the rest of the British army, the Scinde Horse, one of Napier’s cavalry regiments, began to position themselves in a line opposite the Balochi troops, who began to fire on the regiment. Napier himself had to do much of the positioning of the troops, as he lacked experienced commanders within his regiments. As each regiment made its way to the battle, and into position, the fighting grew fierce between both sides.[25] The Balochi troops were well entrenched in their position and, due to the terrain, Napier was unable to get an idea of just how far the Balochi line was and how well it was supported. Soon the British had brought up artillery as well, which opened fire on the Balochi troops in their trenches. As the British approached the left side of Balochi forces, they found themselves faced with heavy attack from the trees, where a large number of troops had positioned themselves.[26]

After almost an hour of fire between both sides, Napier began to see an opportunity to break through a weak spot in the Amir’s lines. The Scinde Horse and 3rd Bombay Light Cavalry made a move to attack the left wing of the British troops and crashed into the Balochis before they could do significant damage.[2] Meanwhile, on the right wing British soldiers charged the Balochi lines, piling over their trenches where the tightly packed Balochi’s found difficulty in using their swords against the British. Seeing the desperation of the Balochis plight Amir Sher Mohammad left the battle at the suggestion of his commander, Hosh Mohammad Kambrani (Also called Hosh Muhammad Shidi), with hopes that he might obtain another chance at victory over the British. Hosh Muhammad, on the other hand, stayed behind with the troops, fighting the British to the death.[27]

The British troops, seeing the centre of the Balochi line giving way, charged through the middle, dividing the Amir’s line. About this time, Napier was almost killed when a magazine exploded near by, killing some British soldiers near him, but sparing his life.[28] One of Napier’s commanders, after breaking through the Balochi left wing then left the field, perhaps aiding later in cutting off the Balochi retreat. The Amir’s men, routed and disorganized, began to flee, and Napier with the Bengal Cavalry pressed on after them, cutting them off from escaping across the Indus. This strategic move on the part of the British stopped the Balochis from regrouping with others and posing a threat to the British. With the Balochis dispersed, Napier returned to his men who celebrated their victor with three cheers.[28] This battle would be one of the last major efforts by Sher Mohammad to resist against the British, which ended on 14 June when British troops surprised the Amir and captured three of his cannons. Sher Mohammad himself escaped to Afghanistan.[29]

Aftermath

Following the British victory, and consequent annexation of the Sindh, troubles quickly arose. Captain James Outram, who had been sent back to England following his posting in the Sindh, began to plead the case of the Amirs in England. Coupled with the new victory, stark criticism arose in England towards both Ellenborough and Napier, who wrote, pleading their own case and arguing over the details of their dealings with the Amirs.[30] The authorities in England were not pleased with the annexation of the Sindh, and had in mind to restore the territory to the Amirs. However, thinking that the process of returning the Sindh to its original owners would be difficult and that the forced resignation of Ellenborough and Napier would cause further criticism from England, the ownerships of the Sindh would remain with the British.[30] The government in England did write to Napier and Ellenbourough, condemning the annexation and their actions. The actual province of Sindh was not as prosperous as Napier had hoped after capture, and for many years the British gained very little from its possession.[31]

References

- Notes

- ↑ Outram, James (2009). The Conquest of Scinde: A Commentary. Bibliolife. p. 451. ISBN 978-0-559-94134-4.

- 1 2 Moon, The British Conquest and Dominion of India, p. 574.

- ↑ Khuhro, Hamida (1998). Mohammed Ayub Khuhro: A Life Of Courage In Politics. Oxford University Press. p. 18. ISBN 969-0-01424-2.

- ↑ Wallis, A History of the British Conquest of Afghanistan and Western India, 1838 to 1849, p. 111.

- 1 2 3 Wallis, A History of the British Conquest of Afghanistan and Western India, 1838 to 1849, p. 113.

- ↑ Wallis, A History of the British Conquest of Afghanistan and Western India, 1838 to 1849, p. 112.

- 1 2 Wallis, A History of the British Conquest of Afghanistan and Western India, 1838 to 1849, p. 114.

- ↑ Wallis, A History of the British Conquest of Afghanistan and Western India, 1838 to 1849, p. 120.

- ↑ Wallis, A History of the British Conquest of Afghanistan and Western India, 1838 to 1849, p. 116.

- ↑ Wallis, A History of the British Conquest of Afghanistan and Western India, 1838 to 1849, p. 118.

- ↑ Duarte, A History of British Relations with Sind, 1613–1843, p. 403–404.

- ↑ Duarte,A History of British Relations with Sind, 1613–1843, p. 405.

- ↑ Moon, The British Conquest and Dominion of India, p. 567.

- ↑ Moon, The British Conquest and Dominion of India, p. 565.

- ↑ Moon, The British Conquest and Dominion of India, p. 565-566.

- ↑ Duarte, A History of British Relations with Sind, 1613–1843, p. 408.

- ↑ Duarte, A History of British Relations with Sind, 1613–1843, p. 409.

- ↑ Duarte, A History of British Relations with Sind, 1613–1843, p. 411.

- 1 2 Lambrick, Sir Charles Napier and Sind, p. 150–151.

- ↑ Lambrick, Sir Charles Napier and Sind, p. 152.

- ↑ Lambrick, Sir Charles Napier and Sind, p. 154–155.

- ↑ Lambrick, Sir Charles Napier and Sind, p. 156.

- 1 2 Lambrick, Sir Charles Napier and Sind, p. 157–158.

- ↑ Lambrick, Sir Charles Napier and Sind, p. 159–160.

- 1 2 Lambrick, Sir Charles Napier and Sind, p. 161.

- ↑ Lambrick, Sir Charles Napier and Sind, p. 163.

- ↑ Lambrick, Sir Charles Napier and Sind, p. 164–165.

- 1 2 Lambrick, Sir Charles Napier and Sind, p. 166.

- ↑ Moon, The British Conquest and Dominion of India, p. 574–575.

- 1 2 Moon, The British Conquest and Dominion of India, p. 575.

- ↑ Moon, The British Conquest and Dominion of India, p. 576.

- Sources

- Duarte, Adrian (1976). A history of British relations with Sind, 1613–1843. Karachi: National Book Foundation. OCLC 3072823.

- Lambrick, H.T. (1952). Sir Charles Napier and Sind. Great Britain: Oxford University Press. ASIN B0007IXTEO.

- Moon, Sir, Penderel (1989). The British Conquest and Dominion of India. Great Britain: Gerald Duckworth &Co. ISBN 978-0253338365.

- Wallis, Frank H. (2009). A History of the British Conquest of Afghanistan and Western India, 1838 to 1849. United Kingdom: The Edwin Mellen Press. ISBN 978-0773446755.