Battle of Hong Kong

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

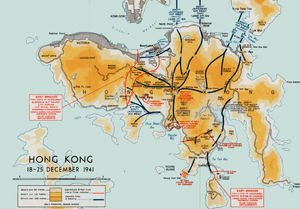

The Battle of Hong Kong (8–25 December 1941), also known as the Defence of Hong Kong and the Fall of Hong Kong, was one of the first battles of the Pacific War in World War II. On the same morning as the attack on Pearl Harbor, forces of the Empire of Japan attacked the British Crown colony of Hong Kong. The attack was in violation of international law as Japan had not declared war against the British Empire. The Japanese attack was met with stiff resistance from the Hong Kong garrison, composed of local troops as well as British, Canadian and Indian units. Within a week the defenders abandoned the mainland and less than two weeks later, with their position on the island untenable, the colony surrendered.

Background

Britain first thought of Japan as a threat with the ending of the Anglo-Japanese Alliance in the early 1920s, a threat that increased with the escalation of the Second Sino-Japanese War. On 21 October 1938 the Japanese occupied Canton (Guangzhou) and Hong Kong was surrounded.[4] British defence studies concluded that Hong Kong would be extremely hard to defend in the event of a Japanese attack but in the mid-1930s, work began on new defences, including the Gin Drinkers' Line. Key sites of the defence of Hong Kong included the Wong Nai Chung Gap, Lye Moon Passage, the Shing Mun Redoubt, the Devil's Peak and Stanley Fort.

By 1940, the British determined to reduce the Hong Kong Garrison to only a symbolic size. Air Chief Marshal Sir Robert Brooke-Popham, the Commander-in-Chief of the British Far East Command argued that limited reinforcements could allow the garrison to delay a Japanese attack, gaining time elsewhere.[5] Winston Churchill and the general staff named Hong Kong as an outpost and decided against sending more troops. In September 1941, they reversed their decision and argued that additional reinforcements would provide a military deterrent against the Japanese and reassure Chinese leader Chiang Kai-shek that Britain was serious about defending the colony.[5]

C Force

In Autumn 1941, the British government accepted an offer by the Canadian Government to send a battalion of the Royal Rifles of Canada (from Quebec) and one of the Winnipeg Grenadiers (from Manitoba) and a brigade headquarters (1,975 personnel) to reinforce the Hong Kong garrison. "C Force", as it was known, arrived on 16 November on board the troopship Awatea and the armed merchant cruiser HMCS Prince David. A total of 96 officers, two Auxiliary Services supervisors and 1,877 other ranks embarked. Included were two medical officers and two nurses (supernumerary to the regimental medical officers), two Canadian Dental Corps officers with assistants, three chaplains and a detachment of the Canadian Postal Corps. (A soldier of the R.C.A.M.C. had stowed away and was sent back to Canada.)[6]

C Force never received its vehicles as the US merchant ship San Jose carrying them was, on the outbreak of the Pacific War, diverted to Manila, in the Philippine Islands, at the request of the US Government.[7] The Royal Rifles had served only in the Dominion of Newfoundland and Saint John, New Brunswick, prior to posting to Hong Kong and the Winnipeg Grenadiers had been deployed to Jamaica. Few Canadian soldiers had field experience but were near fully equipped, except for having only two anti-tank rifles and no ammunition for 2-inch and 3-inch mortars or for signal pistols, deficiencies which the British undertook to remedy at Hong Kong, although not at once.[8]

Battle

8 December 1941

The Japanese attack began shortly after 08:00 on 8 December 1941 (Hong Kong Time), fewer than eight hours after the Attack on Pearl Harbor (because of the day shift that occurs on the international date line between Hawaii and Asia, the Pearl Harbor event is recorded to have occurred on 7 December). British, Canadian and Indian forces, commanded by Major-General Christopher Maltby supported by the Hong Kong Volunteer Defence Corps resisted the Japanese attack by the Japanese 21st, 23rd and the 38th Regiment, commanded by Lieutenant General Takashi Sakai but were outnumbered nearly four to one (Japanese, 52,000; Allied, 14,000) and lacked their opponents' recent combat experience.

The colony had no significant air defence. The RAF station at Hong Kong's Kai Tak Airport (RAF Kai Tak) had only five aeroplanes: two Supermarine Walrus amphibians and three Vickers Vildebeest torpedo-reconnaissance bombers, flown and serviced by seven officers and 108 airmen. An earlier request for a fighter squadron had been rejected and the nearest fully operational RAF base was in Kota Bharu, Malaya, nearly 2,250 kilometres (1,398 miles) away.

Hong Kong also lacked adequate naval defence. Three destroyers were to withdraw to Singapore Naval Base.[9]

Kowloon and New Territories

The Japanese bombed Kai Tak Airport on 8 December.[10] Two of the three Wildebeest and the two Walrus were destroyed by 12 Japanese bombers. The attack also destroyed several civil aircraft including all but two of the aircraft used by the Air Unit of the Hong Kong Volunteer Defence Corp. The RAF and Air Unit personnel from then on fought as ground troops. Two of the Royal Navy's three remaining destroyers were ordered to leave Hong Kong for Singapore. Only one destroyer, HMS Thracian, several gunboats and a flotilla of motor torpedo boats remained.

On 8, 9 and 10 December, eight American pilots of the China National Aviation Corporation (CNAC) and their crews flew 16 sorties between Kai Tak Airport and landing grounds in Namyung and Chongqing (Chungking), the war time capital of the Republic of China.[lower-alpha 3] The crews evacuated 275 persons including Mme Sun Yat-Sen, the widow of Sun Yat-sen and the Chinese Finance Minister Kung Hsiang-hsi.

The Commonwealth forces decided against holding the Sham Chun River and instead established three battalions in the Gin Drinkers' Line across the hills. The Japanese 38th Infantry Division under the command of Major General Takaishi Sakai quickly forded the Sham Chun River over temporary bridges.[10] Early on 10 December, the 228th Infantry Regiment (Colonel Teihichi) of the 38th Division attacked the Commonwealth defences at the Shing Mun Redoubt defended by the 2nd Battalion Royal Scots (Lieutenant Colonel S. White).[10] The line was breached in five hours and later that day the Royal Scots also withdrew from Golden Hill until D company of the Royal Scots counter-attacked and re-captured the hill.[10] By 10:00 a.m. the hill was again taken by the Japanese.[10] This made the situation on the New Territories and Kowloon untenable and the evacuation to Hong Kong Island started on 11 December, under aerial bombardment and artillery fire. As much as possible, military and harbour facilities were demolished before the withdrawal. By 13 December, the 5/7 Rajputs of the Indian Army (Lieutenant Colonel R. Cadogan-Rawlinson), the last Commonwealth troops on the mainland, had retreated to Hong Kong Island.[20]

Hong Kong Island

Maltby organised the defence of the island, splitting it between an East Brigade and a West Brigade. On 15 December, the Japanese began systematic bombardment of the island's North Shore.[20] Two demands for surrender were made on 13 and 17 December. When these were rejected, Japanese forces crossed the harbour on the evening of 18 December and landed on the island's North-East.[20] They suffered only light casualties, although no effective command could be maintained until the dawn came. That night, approximately 20 gunners were executed at the Sai Wan Battery despite having surrendered. There was a further massacre of prisoners, this time of medical staff,[21] in the Salesian Mission on Chai Wan Road.[22][23] In both cases, a few men survived to tell the story.

On the morning of 19 December fierce fighting continued on Hong Kong Island but the Japanese annihilated the headquarters of West Brigade, causing the death of Brigadier John K. Lawson, the commander of the West Brigade .[21] A British counter-attack could not force them from the Wong Nai Chung Gap[21] that secured the passage between the north coast at Causeway Bay and the secluded southern parts of the island. From 20 December, the island became split in two with the British Commonwealth forces still holding out around the Stanley peninsula and in the West of the island. At the same time, water supplies started to run short as the Japanese captured the island's reservoirs.

On the morning of 25 December, Japanese soldiers entered the British field hospital at St. Stephen's College and in the St. Stephen's college incident tortured and killed a large number of injured soldiers, along with the medical staff.[24]

By the afternoon of 25 December 1941, it was clear that further resistance would be futile and British colonial officials headed by the Governor of Hong Kong, Sir Mark Aitchison Young, surrendered in person[25] at the Japanese headquarters on the third floor of the Peninsula Hong Kong hotel. This was the first occasion on which a British Crown Colony had surrendered to an invading force. (British Somaliland which fell to the Italians in August 1940 was a protectorate.) The garrison had held out for 17 days. This day is known in Hong Kong as "Black Christmas".[26]

Massacres

Sai Wan Hill

Perhaps as many as 28 people were massacred after the fight for Sai Wan Hill. These men were members of the 5th Anti-Aircraft Battery of the Hong Kong Volunteer Defence Corps (HKVDC).

Salesian Mission

At Shau Kei Wan there was a Salesian mission being used as an Advanced Dressing Station. On the night of 18 December it was surrounded by troops of the 229th Infantry Regiment. At 0700 on the 19th, Captain Martin Banfill of the Canadian Medical Corps surrendered the station. Two injured officers of the 7th Rajput Regiment were murdered upon arrival in an ambulance. The Japanese separated the male medical staff from the female (two nurses, whose lives were spared). All but three of the men were killed, most of the victims were of the Royal Army Medical Corps but also at least two men of the Royal Rifles of Canada and two civilians.[27]

Causeway Bay

Three captured persons were executed at Causeway Bay, including a female air raid warden with the local Air Raid Precautions (ARP).

Wong Nai Chung Gap

At Wong Nai Chung Gap, ten men of the St. John Ambulance were killed, as well as a policeman and a medic.

Jardine's Lookout

Four men each of the 3rd Company HKVDC and the Winnipeg Grenadiers were massacred after battle at Jardine's Lookout. One Grenadier, a Private Kilfoyle, was killed on the forced march to North Point, according to witnesses.

Black Hole of Hong Kong

Four men were killed in the so-called "Black Hole of Hong Kong", including two Canadian officers.

Blue Pool Road

Around thirty civilians of different ethnicities were massacred at Blue Pool Road.

The Ridge, Overbays and Eucliffe

In the worst massacre of POWs of the battle, the Japanese killed at least 47 after taking The Ridge. Among the dead was Major Charles Sydney Clarke of China Command HQ, two men of the 12th and 20th Coastal Regiments of the Royal Artillery (RA), six men of the Royal Army Service Corps (RASC) and two of the Royal Canadian Army Service Corps (RCASC), nineteen men of the Royal Army Ordnance Corps (RAOC) and three of the Royal Canadian Ordnance Corps (RCOC) and fourteen men of the RASC Company of the HKVDC.

The Japanese also executed at least fourteen captives at Overbays, men of the same units as at The Ridge but also including three Royal Rifles of Canada and an officer of the 1st Battalion, Middlesex Regiment. A further seven were killed at Eucliffe and another 36 known victims cannot be placed precisely at one of the three locations (Ridge, Overbays, Eucliffe). Ride, who was present at the surrender, stated later that he saw fifty bodies lying by the road, including six Middlesex men among them. These men may have been some of those attached to the Hong Kong Chinese Regiment. The Commonwealth War Graves Commission report also states that five men of the Royal Air Force went missing near The Ridge on 20 December, perhaps captured and killed.

Deepwater Bay Ride

Six men of the Middlesex were killed defending PB 14 at Deepwater Bay Ride (Lyon Light). It is uncertain whether they were killed in action, or murdered after capture.

St Stephen's College

The massacre perpetrated at St Stephen's College is the least well-known. Only thirteen victims can be confirmed at the location but reports and estimates put the real number as high as 99. The names of all the reported victims may never be known. Between 75 and 150 bodies were cremated by the victors in the aftermath of the battle but this total includes the victims of the fighting around Stanley Fort, such as the men of 965 Defence Battery. Although it is the "most infamous massacre", it "has been the hardest to match with records."

Three British and four Chinese nurses were said to have been raped and murdered and one Canadian, Captain Overton Stark Hickey of the RCASC, murdered trying to stop the rapes. Besides the raped nurses, the medical staff suffered two deaths, a doctor shot in the head whilst attempting escape and 25 orderlies of the Indian Hospital Corps (IHC) and St John Ambulance personnel. The 55 St John victims of the battle of Hong Kong are memorialised at the present headquarters in Hong Kong but since no dates are given on the memorial it is impossible to identify those killed at St Stephen's. Four Chinese servants and one civilian, Tam Cheung Huen, were killed. Tam is the only Chinese victim of this massacre known by name. Among the soldiers receiving treatment at the college, two riflemen were mutilated and murdered and a further 56 men were reportedly bayoneted in their beds. Some of these men may have been Royal Rifles whose deaths are incorrectly reported as occurring elsewhere on 26 December.

Maryknoll Mission

At least eight men—six of the Middlesex and two Royal Engineers—were killed after capture at Maryknoll Mission. Four members of the 8th Coastal Regiment RA may have been killed here as well; estimates of the number of men murdered vary from 11–16.

Brick Hill

Twenty-six prisoners are believed to have been killed after the fighting for Brick Hill but some of these may have died in the fight, including some of the seventeen men of the Heavy Anti-Aircraft, Hong Kong and Singapore Royal Artillery (HKSRA) known to have died there. Most of the soldiers here murdered were Muslims, including one religious teacher.

Aftermath

Casualties

The Japanese lost at least 1,895 men killed of an estimated 6,000 casualties. Allied casualties were 1,111 men killed, 1,167 missing and 1,362 wounded.[28] Allied dead, including British, Canadian and Indian soldiers, were eventually interred at Sai Wan Military Cemetery and the Stanley Military Cemetery. C Force casualties in the battle were 23 officers and 267 other ranks killed or died of wounds, comprising five officers and 16 other ranks of the Brigade Headquarters, seven officers and 123 men of the Royal Rifles and 11 officers and 128 men of the Winnipeg Grenadiers. C Force also had 28 officers and 465 men wounded. Some of the dead were murdered by Japanese soldiers during or after surrender; Japanese soldiers committed a number of atrocities on 19 December, when the aid post at the Salesian Mission near Sau Ki Wan was overrun.[29] A total of 1,528 soldiers, mainly Commonwealth, are buried there. There are also graves of other Allied combatants who died in the region during the war, including some Dutch sailors who were re-interred in Hong Kong after the war.

The nearby Sai Wan Battery, with buildings constructed as far back as 1890, housed the Depot and Record Office of the Hong Kong Military Service Corps for nearly four decades after the war. The barracks were handed over to the government in 1985 and were subsequently converted into Lei Yue Mun Park and Holiday Village.

At the end of February 1942, The Japanese government stated that numbers of prisoners of war in Hong Kong were: British 5,072, Canadian 1,689, Indian 3,829, others 357, a total of 10,947.[30] They were sent to:

- Sham Shui Po POW Camp

- Argyle Street Camp for officers

- North Point Camp primarily for Canadians and Royal Navy

- Ma Tau Chung Camp for Indian soldiers

- Yokohama Camp in Japan

- Fukuoka Camp in Japan

- Osaka Camp in Japan

Of the Canadians captured during the battle, 267 subsequently perished in Japanese prisoner of war camps, mainly due to neglect and abuse. In December 2011, Toshiyuki Kato, Japan's parliamentary vice-minister for foreign affairs, apologised for the mistreatment to a group of Canadian veterans of the Battle of Hong Kong.[31]

Enemy civilians (meaning Allied nationals) were interned at the Stanley Internment Camp. Initially, there were 2,400 internees although this number was reduced, by repatriations during the war. Internees who died, together with prisoners executed by the Japanese, are buried in Stanley Military Cemetery.

Subsequent operations

Isogai Rensuke became the first Japanese governor of Hong Kong. This ushered in the three years and eight months of Imperial Japanese administration. During the three and half years of occupation by the Japanese, an estimated 10,000 Hong Kong civilians were executed, while many others were tortured, raped, or mutilated.[32] General Takashi Sakai, who led the invasion of Hong Kong and subsequently served as governor for some time, was tried as a war criminal and executed by a firing squad in 1946. The Chinese population waged a small guerrilla war in New Territories. The resistance groups were known as the Gangjiu and Dongjiang forces. As a result of the resistance, some villages were razed as a punishment; the guerillas fought until the end of the Japanese occupation.

Awards

John Robert Osborn (2 January 1899 – 19 December 1941) was awarded the Victoria Cross,[21] the highest and most prestigious award for gallantry in the face of the enemy that can be awarded to British and Commonwealth forces, conferred upon a Canadian for actions during World War II. After seeing a Japanese grenade roll in through the doorway of the building Osborn and his fellow Canadian Winnipeg Grenadiers had been garrisoning, he took off his helmet and threw himself on the grenade, saving the lives of over 10 other Canadian soldiers. He was born in Norfolk, England.

Gander was a Newfoundland dog posthumously awarded the Dickin Medal, the "animals' Victoria Cross", in 2000 for his deeds in World War II, the first such award in over 50 years. He picked up a thrown Japanese hand grenade and rushed with it toward the enemy, dying in the ensuing explosion but saving the lives of several wounded Canadian soldiers.

Colonel Lance Newnham, Captain Douglas Ford and Flight Lieutenant Hector Bertram Gray were awarded the George Cross for the gallantry they showed in resisting Japanese torture in the immediate aftermath of the battle. The men had been captured and were in the process of planning a mass escape by British forces. Their plan was discovered but they refused to disclose information under torture and were shot by firing squad.[33]

Commemoration

The Cenotaph in Central commemorates the defence as well as war-dead from the First World War. The shield in the colonial Emblem of Hong Kong granted in 1959, featured the battlement design to commemorate the defence of Hong Kong during the Second World War. This Coat of Arms was in place until 1997, when it was replaced by the regional emblem. After the war, Lei Yue Mun Fort became a training ground for the British Forces until 1987, when it was vacated. In view of its historical significance and unique architectural features, the former Urban Council decided in 1993 to conserve and develop the fort into the Hong Kong Museum of Coastal Defence.

The memorial garden at Hong Kong City Hall commemorates those who died in Hong Kong during World War II.

Orders of battle

-

Imperial Japanese Army

Imperial Japanese Army

- Twenty-Third Army (Japan) (Lieutenant-General T. Sakai)

- 38th Division (Lieutenant-General T. Ito): 228th, 229th and 230th Infantry Regiments[34]

- Araki Detachment (66th infantry regiment): rearguard

- 2nd Independent Antitank Gun Battalion

- 5th Independent Antitank Gun Battalion

- 10th Independent Mountain Artillery Regiment

- 20th Independent Mountain Artillery Battalion

- 21st Mortar Battalion

- 20th Independent Engineer Regiment

- One radio signal platoon

- One third of medical unit, 51st Division

- 1st&2nd River Crossing Material Company, 9th Division

- Three companies of 3rd Independent Transportation Regiment

- 19th Independent Transport Company

- 20th Independent Transport Company

- 21st Independent Transport Company

- 17th Field Water Purification and Supply Unit

- Twenty-Third Army Air Unit

- 45th Air Regiment

- Element of 44th Independent Air Unit

- Two formations of 10th Independent Air Squad

- 47th Air Field Battalion

- Elements of 67th Air Field Battalion

- 67th Air Field Company

- Twenty-Third Army (Japan) (Lieutenant-General T. Sakai)

-

Imperial Japanese Navy

Imperial Japanese Navy

-

Infantry

Infantry

- 2nd Battalion, The Royal Scots (The Royal Regiment)

- Queen's Own Royal West Kent Regiment

- 1st Battalion, The Middlesex Regiment (Machine gun battalion)

- 5th Battalion, 7th Rajput Regiment

- 2nd Battalion, 14th Punjab Regiment

- 1st Battalion, The Winnipeg Grenadiers

- The Royal Rifles of Canada (Rifle battalion)

- Hong Kong Chinese Regiment (Infantry battalion)

.png)

- Infantry Companies, Hong Kong Volunteer Defence Corps (HKVDC)

.png)

- 2nd Battalion, The Royal Scots (The Royal Regiment)

-

Artillery

Artillery

- 8th Coast Regiment, Royal Artillery

- 12th Coast Regiment, Royal Artillery

- 5th Anti-Air Regiment, Royal Artillery

- 956th Defence Battery, Royal Artillery

- 1st Hong Kong Regiment, Hong Kong and Singapore Royal Artillery

.png) /

/ .svg.png)

- Artillery Batteries, Hong Kong Volunteer Defence Corps (HKVDC)

.png)

- 8th Coast Regiment, Royal Artillery

-

Supporting Units

Supporting Units

- Royal Engineers, RE

- Royal Army Service Corps, RASC

- Royal Army Medical Corps, RAMC

- Royal Signals, RS

- Royal Army Ordnance Corps, RAOC

- Royal Army Dental Corps, RADC

- Royal Army Pay Corps, RAPC

- Military Provost Staff Corps

- Indian Hospital Corps, IHC

- Indian Medical Service, IMS

- Royal Indian Army Service Corps, RIASC

- Hong Kong Mule Corps

- Corps of Military Staff Clerks

- Canadian Provost Corps

- Royal Canadian Army Medical Corps, RCAMC

- Canadian Army Dental Corps

- Canadian Service

- Royal Canadian Corps of Signals, RCCS

- Royal Canadian Army Service Corps, RCASC

- Royal Canadian Army Pay Corps, RCAPC

- Canadian Postal Corps

- Royal Canadian Ordnance Corps, RCOC

- Canadian Chaplains Service

- Canadian Auxiliary Services

- Supporting Units, Hong Kong Volunteer Defence Corps (HKVDC)

.png)

- Royal Engineers, RE

Notes

- ↑ Figures taken from Christopher Maltby, the Commander British Forces in Hong Kong[1]

- ↑ Figures taken from Selwyn Selwyn-Clarke, the Director of Medical Services in Hong Kong.[3]

- ↑ Articles in the New York Times and the Chicago Daily of 15 December 1941,[11] the pilots were Charles L. Sharp,[12] Hugh L. Woods,[13] Harold A. Sweet,[14] William McDonald,[15] Frank L. Higgs,[16] Robert S. Angle,[17] P. W. Kessler[18] and S. E. Scott.[19]

Footnotes

- ↑ Banham 2005, p. 317.

- ↑ Ishiwari 1956, pp. 47–48.

- ↑ Banham 2005, p. 318.

- ↑ Fung 2005, p. 129.

- 1 2 Harris 2005.

- ↑ Stacey 1956, p. 448.

- ↑ Stacey 1956, p. 449.

- ↑ Stacey 1956, pp. 448–449.

- ↑ L, Klemen (1999–2000). "Chronology of the Dutch East Indies, 1 December 1941 – 6 December 1941". Forgotten Campaign: The Dutch East Indies Campaign 1941–1942.

- 1 2 3 4 5 L., Klemen (1999–2000). "Chronology of the Dutch East Indies, 7 December 1941 – 11 December 1941". Forgotten Campaign: The Dutch East Indies Campaign 1941–1942.

- ↑ http://www.cnac.org

- ↑ Charles L. Sharp

- ↑ Hugh L. Woods

- ↑ Harold A. Sweet

- ↑ William McDonald

- ↑ Frank L. Higgs

- ↑ Robert S. Angle

- ↑ P.W. Kessler

- ↑ S.E. Scott

- 1 2 3 L., Klemen (1999–2000). "Chronology of the Dutch East Indies, 12 December 1941 – 18 December 1941". Forgotten Campaign: The Dutch East Indies Campaign 1941–1942.

- 1 2 3 4 L, Klemen (1999–2000). "Chronology of the Dutch East Indies, 19 December 1941 – 24 December 1941". Forgotten Campaign: The Dutch East Indies Campaign 1941–1942.

- ↑ Nicholson 2010, p. xv.

- ↑ "Battle of Hong Kong 8 Dec 1941 – 25 Dec 1941". World war II Database.

- ↑ Charles G. Roland. "Massacre and Rape in Hong Kong: Two Case Studies Involving Medical Personnel and Patients". (subscription required (help)).

- ↑ L., Klemen (1999–2000). "Chronology of the Dutch East Indies, 25 December 1941 – 31 December 1941". Forgotten Campaign: The Dutch East Indies Campaign 1941–1942.

- ↑ "Hong Kong's 'Black Christmas". China Daily. 8 December 2008. Retrieved 19 December 2013.

- ↑ Banham 2005, p. 129.

- ↑ Mackenzie 1951, p. 214.

- ↑ Stacey 1956, p. 488.

- ↑ Official Report of the Debates of The House of Commons of The Dominion Of Canada (Volume 2) 1942 (page 1168)

- ↑ Associated Press, "Japan apologizes to Canadian POWs from H.K. battle", Japan Times, 10 December 2011, p. 2.

- ↑ Carroll 2007, p. 123.

- ↑ Turner 2010, p. 85.

- ↑ Woodburn Kirby 2004, p. 498.

Bibliography

- Banham, Tony (2005). Not the Slightest Chance: The Defence of Hong Kong, 1941. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press. ISBN 9622097804.

- Carroll, J. M. A Concise History of Hong Kong. Critical Issues in History. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 0-74253-421-9.

- Fung, Chi Ming (2005). Reluctant Heroes: Rickshaw Pullers in Hong Kong and Canton, 1874–1954 (illus. ed.). Hong Kong University Press. ISBN 978-962-209-734-6.

- Harris, John R. (2005). The Battle for Hong Kong 1941–1945. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press. ISBN 978-962-209-779-7.

- Ishiwari, Heizō (31 May 1956). Army Operations in China, December 1941 – December 1943 (PDF). Japanese Monograph. IV 17807.71-2. Washington, DC: Office of the Chief of Military History, Department of the Army. OCLC 938077822. Retrieved 30 July 2016.

- Mackenzie, Compton (1951). Eastern Epic: September 1939 – March 1943, Defence. I. London: Chatto & Windus. OCLC 59637091.

- Nicholson, Brian (2010). Traitor. Bloomington, IN: Trafford. ISBN 978-1-4269-4604-2.

- Stacey, C. P. (1956) [1955]. Six Year of War: The Army in Canada, Britain and the Pacific (PDF). Official History of the Canadian Army in the Second World War. I (2nd rev. online ed.). Ottawa: By Authority of the Minister of National Defence. OCLC 917731527. Retrieved 12 December 2015.

- Turner, John Frayn (2010) [2006]. Awards of the George Cross 1940–2009 (online, Pen & Sword, Barnsley ed.). Havertown, PA: Casemate. ISBN 978-1-78340-981-5.

- Woodburn Kirby, S.; et al. (2004) [1957]. Butler, J. R. M., ed. The War Against Japan: The Loss of Singapore. History of the Second World War United Kingdom Military Series. I (Naval & Military Press ed.). London: HMSO. ISBN 1-84574-060-2.

Further reading

- Banham, Tony (2009). We Shall Suffer There: Hong Kong's Defenders Imprisoned, 1942–1945. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press. ISBN 978-962-209-960-9.

- Burton, John (2006). Fortnight of Infamy: The Collapse of Allied Airpower West of Pearl Harbor. Annapolis, MD: US Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-59114-096-X.

- Roland, Charles G. (2001). Long Night's Journey into Day: Prisoners of War in Hong Kong and Japan, 1941–1945. Waterloo, OT: Wilfrid Laurier University Press. ISBN 0-88920-362-8.

- Snow, Philip (2003). The Fall of Hong Kong: Britain, China and the Japanese Occupation. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-10373-5.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Battle of Hong Kong. |

- Hong Kong Veterans Commemorative Association – Canada

- Hong Kong Category. WW2 People's War. BBC

- Official report by Major-General C.M Maltby, G.O.C. Hong Kong

- Canadians at Hong Kong – Canadians and the Battle of Hong Kong.

- The Defence of Hong Kong: December 1941 by Terry Copp at the Internet ArchivePDF (archived from the original on 2008-05-28)

- Report No. 163 Canadian Participation in the Defence of Hong Kong, December, 1941 at the Internet ArchivePDF (299 KB) (Archived version as of 24 August 2006)

- Hong Kong War Diary – Current research into the Battle

- Battle of Hong Kong Background and Battlefield Tour Points of Interest by Tony Banham

- "The detailed story of the actual battle and a tribute to Major Maurice A. Parker, CO "D" Coy, Royal Rifles of Canada." at the Wayback Machine (archived 28 October 2009)

- Philip Doddridge, Memories Uninvited – "A fascinating story of a young man who finds himself caught up in the horrific battle for Hong Kong and the years of captivity he lived through after the battle was over on December 25th, 1941."

Coordinates: 22°16′01″N 114°11′17″E / 22.267°N 114.188°E