Battle of Bannockburn

Coordinates: 56°05′31″N 3°54′54″W / 56.092°N 3.915°W

| Battle of Bannockburn | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the First War of Scottish Independence | |||||||

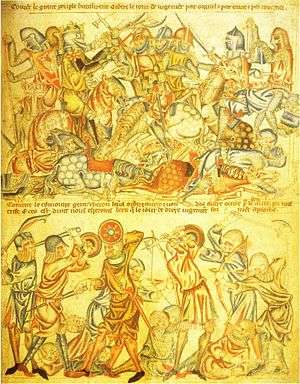

This depiction from the Scotichronicon (c.1440) is the earliest known image of the battle. King Robert wielding an axe and Edward II fleeing toward Stirling feature prominently, conflating incidents from the two days of battle. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Sir Robert Keith, Marischal of Scotland |

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 5,000[1]–10,000[2] | 13,700[3]–25,000[4] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 400[5]–4,000[6] |

700 cavalry[7] 4,000[8]–11,000 infantry[9] | ||||||

The Battle of Bannockburn (Blàr Allt nam Bànag, often mistakenly called Blàr Allt a' Bhonnaich in Scottish Gaelic) (24 June 1314) was a significant Scottish victory in the First War of Scottish Independence, and a landmark in Scottish history.

Stirling Castle, a Scots royal fortress, occupied by the English, was under siege by the Scottish army. The English king, Edward II, assembled a formidable force to relieve it. This attempt failed, and his army was defeated in a pitched battle by a smaller army commanded by the King of Scots, Robert the Bruce.

Background

The Wars of Scottish Independence between England and Scotland began in 1296 and initially the English were successful under the command of Edward I, having won victories at the Battle of Dunbar (1296) and at the Capture of Berwick (1296).[10] The removal of John Balliol from the Scottish throne also contributed to the English success.[10] The Scots had been victorious in defeating the English at the Battle of Stirling Bridge in 1297, however this was countered by Edward I's victory at the Battle of Falkirk (1298).[10] By 1304 Scotland had been conquered, but in 1306 Robert the Bruce seized the Scottish throne and the war was reopened.[10]

Edward II of England came to the throne in 1307 but was incapable of providing the determined leadership that had been shown by his father, Edward I, and the English position soon became more difficult.[10] Stirling Castle was one of the most important castles that was held by the English as it commanded the route north into the Scottish Highlands.[10] It was besieged in 1314 by Robert the Bruce's brother, Edward Bruce, and an agreement was made that if the castle was not relieved by mid-summer then it would be surrendered to the Scots.[10] The English could not ignore this challenge and military preparations were made for a substantial campaign in which the English army probably numbered 2,000 cavalry and 15,000 infantry, many of whom would have been longbowmen.[10] The Scottish army probably numbered between 7,000 and 10,000 men, of whom no more than 500 would have been mounted.[10] Unlike the heavily armoured English cavalry, the Scottish cavalry would have been light horsemen who were good for skirmishing and reconnaissance but were not suitable for charging the enemy lines.[10] The Scottish infantry would have had axes, swords and pikes, with few bowmen among them.[10]

The precise size of the English force relative to the Scottish forces is unclear but estimates range from as much as at least two or three times the size of the army Bruce had been able to gather, to as little as only 50% larger.[11]

Prelude

Edward II and his advisors were aware of the places that the Scots were likely to challenge them and sent out orders for their troops to prepare for an enemy established in boggy ground near to the River Forth, near Stirling.[10] The English appear to have advanced in four divisions whereas the Scots were in three divisions, known as 'schiltrons' which were strong defensive circles of men bristling with pikes.[10] Thomas Randolph, 1st Earl of Moray, commanded the Scottish vanguard, which was stationed about a mile to the south of Stirling, near the church of St. Ninian, while the king commanded the rearguard at the entrance to the New Park. His brother Edward led the third division. According to Barbour, there was a fourth division nominally under the youthful Walter the Steward, but actually under the command of Sir James Douglas.[12] The Scottish archers used yew-stave longbows and though these were not weaker or inferior to English longbows, there were fewer Scottish archers than English archers,[13] possibly numbering only 500. These archers played little part in the battle.[14] There is firsthand evidence in a poem by the captured Carmelite friar Robert Baston, written just after the battle, that one or both sides employed slingers and crossbowmen.[15]

Battle

Location of the battlefield

There is some confusion over the exact site of the Battle of Bannockburn, although most modern historians agree that the traditional site, where a visitor centre and statue have been erected, is not the correct one.[16] Although a large number of possible alternatives have been proposed, most can be dismissed leaving two serious contenders:[17]

- the area of peaty ground known as the Dryfield outside the village of Balquhiderock, about three-quarters of a mile to the east of the traditional site,[18] and

- the Carse of Balquhiderock, about a mile and a half north-east of the traditional site, accepted by the National Trust as the most likely candidate.[19]

First day of battle

Most medieval battles were short-lived, lasting only a few hours, therefore the Battle of Bannockburn is unusual in that it lasted for two days.[10] On 23 June 1314 two of the English cavalry formations advanced, the first commanded by the Earl of Gloucester and the Earl of Hereford.[10] They encountered a body of Scots, among them Robert the Bruce himself.[10] A celebrated single combat then took place between Bruce and Henry de Bohun who was the nephew of the Earl of Hereford.[10] Bohun charged at Bruce and when the two passed side by side, Bruce split Bohun's head with his axe.[10][20] The Scots then rushed upon the English under Gloucester and Hereford who struggled back over the Bannockburn.[21]

The second English cavalry force was commanded by Robert Clifford and Henry de Beaumont and included Sir Thomas de Grey of Heaton, father of the chronicler Thomas Grey whose account of events follows; "Robert Lord de Clifford and Henry de Beaumont, with three hundred men-at-arms, made a circuit upon the other side of the wood towards the castle, keeping the open ground. Thomas Randolph, 1st Earl of Moray, Robert de Brus's nephew, who was leader of the Scottish advanced guard, hearing that his uncle had repulsed the advanced guard of the English on the other side of the wood, thought that he must have his share, and issuing from the wood with his division marched across the open ground towards the two afore-named lords.

Sir Henry de Beaumont called to his men: "Let us wait a little; let them come on; give them room"

"Sir," said Sir Thomas Gray, "I doubt that whatever you give them now, they will have all too soon"

"Very well" exclaimed the said Henry, if you are afraid, be off"

"Sir," answered the said Thomas, "it is not from fear that I shall fly this day."

So saying he spurred in between Beaumont and Sir William Deyncourt, and charged into the thick of the enemy. William was killed, Thomas was taken prisoner, his horse being killed on the pikes, and he himself carried off with the Scots on foot when they marched off, having utterly routed the squadron of the said two lords. Some of the English fled to the castle, others to the king's army, which having already left the road through the wood had debouched upon a plain near the water of Forth beyond Bannockburn, an evil, deep, wet marsh, where the said English army unharnessed and remained all night, having sadly lost confidence and being too much disaffected by the events of the day." [22]

Second day of battle

Under nightfall the English forces crossed the stream that is known as the Bannock Burn, establishing their position on the plain beyond it.[10] A Scottish knight, Alexander Seton, who was fighting in the service of Edward II of England, deserted the English camp and told Bruce of the low English morale, encouraging Bruce to attack them.[10] In the morning the Scots then advanced from New Park.[10]

Not long after daybreak, the Scots spearmen began to move towards the English. Edward was surprised to see Robert's army emerge from the cover of the woods. As Bruce's army drew nearer, they paused and knelt in prayer. Edward is supposed to have said in surprise "They pray for mercy!" "For mercy, yes," one of his attendants replied, "But from God, not you. These men will conquer or die."[23] The English responded to the Scots advance with a charge of their own, led by the Earl of Gloucester. Gloucester had argued with the Earl of Hereford over who should lead the vanguard into battle, and argued with the king that the battle should be postponed. This led the king to accuse him of cowardice, which perhaps goaded Gloucester into the charge.[10] Few accompanied Gloucester in his charge and when he reached the Scottish lines he was quickly surrounded and killed.[10] Gradually the English were pushed back and ground down by the Scots' schiltrons.[10] The English longbowmen attempted to support the advance of the knights but were ordered to stop shooting, as they were causing casualties among their own. An attempt to employ the English and Welsh longbowmen to shoot at the advancing Scots from their flank failed when they were dispersed by 500 Scottish cavalry under the Marischal Sir Robert Keith.[24] Although sometimes described as light cavalry, this appears to be a misinterpretation of Barbour's statement that these were men-at arms on lighter horses than their English counterparts.[25] The English cavalry was hemmed in making it difficult for them to manoeuvre.[10] As a result, the English were unable to hold their formations and broke ranks.[10] It soon became clear to Aymer de Valence, 2nd Earl of Pembroke and Giles d'Argentan (reputedly the third best knight in Europe) that the English had lost and Edward II needed to be led to safety at all costs, so, seizing his horse's reins, dragged him away, and were closely followed by five hundred knights of the royal bodyguard.[26] Once they were clear of the battle d'Argentan turned to the king, said "Sire, your protection was committed to me, but since you are safely on your way, I will bid you farewell for never yet have I fled from a battle, nor will I now." and turned his horse to charge back into the ranks of Scottish where he was overborn and slain.[27]

English retreat

Edward fled with his personal bodyguard, ending the remaining order in the army; panic spread and defeat turned into a rout. He arrived eventually at Dunbar Castle, from which he took ship to Berwick. From the carnage of Bannockburn, the rest of the army tried to escape to the safety of the English border, ninety miles to the south. Many were killed by the pursuing Scottish army or by the inhabitants of the countryside that they passed through. Historian Peter Reese says that, "only one sizeable group of men—all foot soldiers—made good their escape to England."[9] These were a force of Welsh spearmen who were kept together by their commander, Sir Maurice de Berkeley, and the majority of them reached Carlisle.[9] Weighing up the available evidence, Reese concludes that "it seems doubtful if even a third of the footsoldiers returned to England."[9] Out of 16,000 infantrymen, this would give a total of about 11,000 killed. The English chronicler Thomas Walsingham gave the number of English men-at-arms who were killed as 700,[7] while 500 more men-at-arms were spared for ransom.[28] The Scottish losses appear to have been comparatively light, with only two knights among those killed.[29]

Aftermath

The defeat of the English opened up the north of England to Scottish raids[10] and allowed the Scottish invasion of Ireland.[24] These finally led, after the failure of the Declaration of Arbroath to reach this end by diplomatic means, to the Treaty of Edinburgh–Northampton.[24] Under the treaty the English Crown recognised the full independence of the Kingdom of Scotland, and acknowledge Robert the Bruce, and his heirs and successors, as the rightful rulers.

It was not until 1332 that the Second War of Scottish Independence began with the Battle of Dupplin Moor, followed by the Battle of Halidon Hill (1333) which were won by the English.[10]

Notable casualties

Deaths

- Gilbert de Clare, 8th Earl of Gloucester

- Sir Giles d'Argentan

- John Lovel, 2nd Baron Lovel

- John Comyn, Lord of Badenoch

- Robert de Clifford, 1st Baron de Clifford

- Sir Henry de Bohun

- William le Marshal, Marshal of Ireland

- Edmund de Mauley, King's Steward

- Sir Robert de Felton of Litcham, 1st Lord

Captives

- Humphrey de Bohun, 4th Earl of Hereford

- John Segrave, 2nd Baron Segrave

- Maurice de Berkeley, 2nd Baron Berkeley

- Thomas de Berkeley

- Sir Marmaduke Tweng

- Ralph de Monthermer, 1st Baron Monthermer

- Robert de Umfraville, Earl of Angus

- Sir Anthony de Luci

- Sir Ingram de Umfraville

- Sir John Maltravers, 1st Baron Maltravers

- Sir Thomas de Grey of Heaton

Legacy

Bannockburn Visitor Centre

In 1932 the Bannockburn Preservation Committee, under Edward Bruce, 10th Earl of Elgin and Kincardine, presented lands to the National Trust for Scotland. Further lands were purchased in 1960 and 1965 to facilitate visitor access. A modern monument stands in a field above the battle site, where the warring parties are believed to have camped on the night before the battle. The monument consists of two hemicircular walls depicting the opposing parties. Nearby stands the 1960s statue of Bruce by Pilkington Jackson. The monument, and the associated visitor centre, is one of the most popular tourist attractions in the area. The battlefield has been included in the Inventory of Historic Battlefields in Scotland and protected by Historic Scotland under the Historic Environment (Amendment) Act 2011.[30]

-

Alley to the monument

-

Statue of Robert the Bruce by Pilkington Jackson

-

View of the circular walls and the flag pole

-

Close Up of the statue

The National Trust for Scotland operates the Bannockburn Visitor Centre (previously known as the Bannockburn Heritage Centre), which is open daily from March through October. On 31 October 2012 the building was closed[31] for demolition and replacement by a new design, inspired by traditional Scottish buildings, by Reiach and Hall Architects. The project is a partnership between the National Trust for Scotland and Historic Scotland, funded by the Scottish Government and the Heritage Lottery Fund.[32] The battlefield's new visitor centre - now rebranded as the Bannockburn Visitor Centre - opened in March 2014. One of the attractions created by a £9m redevelopment of the centre and the nearby battlefield memorial is a computerised multiplayer game.[33]

Arts

"Scots Wha Hae" is the title of a patriotic poem by Robert Burns.[34] The chorus of Scotland's unofficial national anthem Flower of Scotland refers to Scotland's victory over Edward and the English at Bannockburn.

References

- ↑ Nusbacher, Aryeh (2000). The Battle of Bannockburn 1314. Stroud: Tempus. p. 85. ISBN 0-7524-1783-5.

- ↑ Oman, Charles (1991) [1924]. A History of the Art of War in the Middle Ages Vol. II. London: Greenhill Books. p. 88. ISBN 1-85367-105-3.

- ↑ Armstrong, Pete (2002). Bannockburn. Botley, Oxford: Osprey Publishing. p. 43. ISBN 1-85532-609-4.

- ↑ Grant, R.G. (2008), Battle: A visual journey through 5,000 years of combat, DK Publishing,p.118.

- ↑ Sadler, John, Scottish Battles, (Biddles Ltd., 1998), 52–54.

- ↑ Grant, 118.

- 1 2 Mackenzie, p.88 referencing Walsingham, p.141

- ↑ Sadler, 52.

- 1 2 3 4 Reese, p.174

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 Black, Jeremy. (2005). The Seventy Great Battles of All Time. pp. 71–73. Thames & Hudson Ltd. ISBN 0-500-25125-8.

- ↑ Watson, F., "In Our Time: The Battle of Bannockburn", BBC Radio, 3 February 2011

- ↑ Nicholson, Later Middle Ages pp.87–89

- ↑ Strickland, Matthew; Hardy,Robert (2005). The Great Warbow. Stroud: Sutton. p. 162. ISBN 0-7509-3167-1.

- ↑ The Chronicle of Lanercost says that on the second day of the battle, "the English archers were thrown forward before the line, and the Scottish archers engaged them, a few being killed and wounded on either side; but the King of England's archers quickly put the others to flight." The Chronicle of Lanercost, 1272–1346: Translated, with notes by Sir Herbert Maxwell. p. 206

- ↑ Walter Bower, Scotichronicon,Book XII, p. 371

- ↑ Mackenzie, W. M. (1913). The Battle of Bannockburn: a Study in Mediaeval Warfare, Publisher: James MacLehose; Glasgow.

- ↑ Barrow, Geoffrey W.S. (1998). Robert Bruce & The Community of The Realm of Scotland. ISBN 0-85224-604-8

- ↑ Barron, E.M., The Scottish War of Independence: a Critical Study, 1934

- ↑ Christison, Philip, Bannockburn: The Story of the Battle, 1960, Edinburgh: The National Trust for Scotland.

- ↑ Hyland, Ann. The Warhorse 1250–1600, UK: Sutton Publishing, 1998, p 38

- ↑ The Battle of Bannockburn britishbattles.com. Retrieved 14 June 2014.

- ↑ Maxwell 1907

- ↑ Scott 1982, p. 158

- 1 2 3 Scott 1982

- ↑ (Brown, C. (2008) pp 129-130)

- ↑ Scott 1982, p. 159

- ↑ Scott 1982, p. 160

- ↑ Mackenzie, p.90

- ↑ Reese, p.176

- ↑ "Inventory battlefields". Historic Scotland. Retrieved 2012-04-12.

- ↑ "Bannockburn Heritage Centre closes before demolition". BBC News. 31 October 2012. Retrieved 31 October 2012.

- ↑ "Battle of Bannockburn: Bannockburn : About the project".

- ↑ "Battle of Bannockburn: : The Battle of Bannockburn Visitor Centre Opens".

- ↑ The Complete Works of Robert Burns at Project Gutenberg.

Sources

Primary

- Barbour, John, The Brus, trans. A. A. M. Duncan, 1964.

- Bower, Walter, Scotichronicon, ed. D. E. R. Watt, 1987–1993.

- Maxwell, Herbert, trans. (1907). Scalacronica; The reigns of Edward I, Edward II and Edward III as Recorded by Sir Thomas Gray. Glasgow: James Maclehose & Sons. Retrieved 17 October 2012.

- Lanercost Chronicle, edited and translated by H. Maxwell, 1913.

- Vita Edwardi Secundi (Life of Edward the Second), ed. N. D. Young, 1957.

- Walsingham, Thomas, Historia Anglicana.

Secondary

- Armstrong, Pete (illustrated by Graham Turner), Bannockburn 1314: Robert Bruce's Great Victory, Osprey Publishing, 2002 ISBN 1-85532-609-4

- Barrow, G. W. S., Robert Bruce and the Community of the Realm of Scotland, 1988,ISBN 0-85224-604-8

- Brown, C.A., "Bannockburn 1314",History Press,Stroud, 2008, ISBN 978-0-7524-4600-4.

- Brown, C.A., Robert the Bruce. A life Chronicled.

- Brown, Michael (2008). Bannockburn. The Scottish War and the British Isles 1307-1323. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

- Brown, M., Wars of Scotland

-

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Bannockburn". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Bannockburn". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. - Mackenzie, W. M., Bannockburn: A Study in Medieval Warfare, The Strong Oak Press, Stevenage 1989 (first published 1913), ISBN 1-871048-03-6

- MacNamee, C., The Wars of the Bruces

- Nicholson, R., Scotland-the Later Middle Ages, 1974.

- Prestwich, M., The Three Edwards: War and State in England, 1272–1377, 1980

- Ramsay, J. H., The Genesis of Lancaster, 1307–99, 1913.

- Reese, P., Bannockburn, Canongate, Edinburgh, 2003, ISBN 1-84195-465-9

- Scott, Ronald McNair (1982). Robert the Bruce King of Scots. London: Hutchinson & Co.

External links

- The Battle of Bannockburn 700th Anniversary Project

- Battle of Bannockburn on Medieval Archives Podcast

- BBC "In our time" discussion on the battle and it's consequences