Battle of Łódź (1914)

| Battle of Łódź | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Eastern Front during World War I | |||||||

Eastern Front September 28 – November 1, 1914 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Erich Ludendorff August von Mackensen |

North-Western Front: Nikolai Ruzsky 1st Army: Rennenkampf, 2nd Army: Scheidemann, 5th Army: Plehve | ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

| German Ninth Army |

Russian First Army Russian Second Army Russian Fifth Army | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 250,000 troops[1] | 500,000 troops[2] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 35,000 killed, wounded or captured[3] | 90,000 killed, wounded or captured[4] | ||||||

The Battle of Łódź took place from November 11 to December 6, 1914, near the city of Łódź in Poland. It was fought between the German Ninth Army and the Russian First, Second, and Fifth Armies, in harsh winter conditions.

Background

By September 1914 the Russians had defeated the Austro-Hungarians in the Battle of Galicia, the Austro-Hungarian retreat isolated their fortress of Przemyśl, which was besieged by the Russian Eighth Army. The armies on the Russian Northeast Front, commanded by Nikolai Ruzsky, had driven the outnumbered Germans back out of Poland in the Battle of the Vistula River, although the German incursion had postponed the projected Russian invasion into German Silesia. The Russian high command considered how to capitalize on their recent successes. Grand Duke Nicholas Nikolayevich favored an offensive into East Prussia, while his Chief of Staff, Mikhail Alekseev, favored an invasion of Silesia, as soon as they had repaired the extensive damage the Germans had done to the roads and railways on the Polish side of the border.

On 1 November Paul von Hindenburg was appointed commander of the two German armies on the Eastern Front. His Eighth Army was defending East Prussia, it was withdrawn from the frontier to occupy a defensive line. The Russians followed, attacking the line and re-occupying the eastern parts of the province, so its inhabitants fled once again. Hindenburg's Ninth Army, under General August von Mackensen, was on the border between Poland and Silesia. Intercepted, decoded Russian wireless messages revealed that Silesia would be invaded on 14 November. Hindenburg and Ludendorff decided not to meet the attack head-on, but to seize the initiative by shifting their Ninth Army north by railway to the border south of the German fortress at Thorn, where they would be reinforced with two corps transferred from Eighth Army. The enlarged Ninth Army would then attack the Russian right flank.[5] In ten days Ninth Army was moved north by running 80 trains every day.[6] Conrad von Hotzendorf, the Austrian commander, transferred the Austrian Second Army from the Carpathians to take over the German Ninth Army's former position.

General Nikolai Ruzsky had recently assumed command of the Russian Northwest Army Group defending Warsaw. Ruzsky had under his command General Paul von Rennenkampf's Russian First Army, most of which was on the right bank of the Vistula River, only one corps was on the left bank. Ruzsky also directed the Russian Second Army, under General Scheidemann, which was positioned in front of the city of Łódź. Both armies were still in summer clothing and the Russians were short of artillery ammunition.

Central Powers Forces [7]

[North to South]

- 9th Army [as of Nov. 11, 1914] – Gen. Mackensen

- Corps "Thorn" - Gen. Dickhuth-Harrach; (99th Reserve Infantry Brigade of 50th Reserve Infantry Division, 21st Landwehr Infantry Brigade, Brigade "Westernhagen" [Landwehr & Landsturm]);

- XXV Reserve Corps (49th Reserve Infantry Division & 100th Reserve Infantry Brigade of 50th Reserve Infantry Division);

- I Reserve Corps (1st & 36th Reserve Infantry Divisions);

- HHK 1 – Gen. Richtofen (6th & 9th Cavalry Divisions);

- XX Corps (37th & 41st Infantry Divisions);

- XVII Corps (35th & 36th Infantry Divisions);

- XI Corps (22nd & 38th Infantry Divisions);

- HHK 3 – Gen. Frommel (5th, 8th & Austrian 7th Cavalry Divisions);

- Landsturm Brigade "Doussin" (part of Corps "Posen")

- In reserve: 3rd Guard Infantry Division.

- Reinforcements:

- Arrived starting mid-November:

- Approximately 5 towed foot artillery battalions from the eastern fortresses and the West, with 10 batteries of 21 cm heavy howitzers plus 1 Austro-Hungarian 30.5 cm siege howitzer battery

- Mid-November:

- Corps "Posen" (four weak brigades composed of Landwehr, Ersatz and Landsturm troops) Koch

- End of November:

- II Corps (3rd & 4th Infantry Divisions) from the west (later one brigade of 3rd Inf. Div. to Corps "Gerok");

- 1st Infantry Division from I Corps of 8th Army in East Prussia;

- Corps "Gerok" (48th Infantry Division) from the west;

- Corps "Breslau" (Division "Menges" & Brigade "Schmiedecke") (later added to Corps "Gerok");

- 4th Cavalry Division from southern part of the East Prussian front.

- Beginning of December:

- Corps "Fabek"(26th Infantry Division & 25th Reserve Infantry Division) from the west;

- III Reserve Corps (5th & 6th Reserve Infantry Divisions) from the west.

- Mid-December:

- 1st Guard Reserve Infantry Division from Army "Woyrsch".

Russian Forces [8]

Northwestern Front - Gen. Ruzsky

- 1st Army - Gen. Rennenkampf (from 2 Dec. Gen. Litvinov)

- 4th Don Cossack Division

- I Turkestan Corps (1st & 2nd Turkestan Rifle Brigades, 11th Siberia Rifle Division)

- Ussuri Mounted Brigade

- 6th Cavalry Division

- VI Corps (4th & 16th Infantry Divisions)

- Combined Cossack Division

- VI Siberia Corps (13th & 14th Siberia Rifle Divisions)

- V Siberia Corps (50th & 79th Infantry Divisions)

- Guard Cossack Division

- Reinforcements:

- II Corps from 2nd Army (see below);

- 6th Siberia Rifle Division from 10th Army;

- ½ 63rd Reserve Division & the Rifle Officers’ School Regiment from Warsaw fortified area;

- 3rd Turkestan Rifle Brigade;

- 55th & 67th Infantry Divisions from army reserve;

- 2nd Army - Gen. Scheidemann

- Caucasus Cavalry Division;

- II Corps (26th & 43rd Infantry Divisions);

- Cavalry Corps "Novikov" (5th, 8th & 14th Cavalry Divisions);

- XXIII Corps (3rd Guard Infantry Division, one brigade of 2nd Infantry Division, 1st Rifle Brigade);

- II Siberia Corps (4th & 5th Siberia Rifle Divisions);

- IV Corps (30th & 40th Infantry Divisions);

- I Corps (22nd & 24th Infantry Divisions);

- Reinforcements in Dec:

- 2nd Cavalry Division from 10th Army;

- 62nd Reserve Division from army reserve;

- 5th Army - Gen. Plehve

- I Siberia Corps (1st & 2nd Siberia Rifle Divisions);

- XIX Corps (17th & 38th Infantry Divisions);

- V Corps (5th & 10th Infantry Divisions);

- 5th Don Cossack Division;

- Turkmen Cossack Brigade.

The Battle

The Russians had no inkling that the Germans had moved north, so they were stunned on November 11 when Mackensen's German Ninth Army struck V Siberia Corps of Rennenkampf's First Army, his only unit on the left bank of the Vistula. The Siberians were routed, 12,000 were taken prisoner. The Siberians were unable to dig effective defensive positions because they had few shovels and the ground froze at night.[9] The Germans were forcing open a corridor between Łódź and Warsaw, creating a 50 km (31 mi) gap between the Russian First and Second Armies. Scheidemann's Russian Second Army retreated eastward towards Łódź, they were threatened with encirclement. Rennenkampf wanted to support V Siberia Corps by moving more men across the Vistula, but Ruzsky suspected that the target was Warsaw, so First Army remained in place.

Grand Duke Nicholas's primary objective was saving Second Army and avoiding a repeat of the disaster at Tannenberg. On 16 November he ordered Wenzel von Plehve's Russian Fifth Army to abandon the proposed offensive into Silesia and to move northward towards Łódź; they marched 116 km (72 mi) in only two days. As soon as Hindenburg saw the transcript of this order he knew that his maneuver had succeeded. Now seven Russian corps were defending the city. Plehve smashed into Mackensen's right flank on November 18 in bitter winter conditions (at times the temperature dropped as low as 10 °F (−12 °C)).[10]

The German Ninth Army's right wing was XXV Reserve Corps, commanded by Lieutenant General Freiherr Reinhard von Sheffer-Boyadel, a 63-year-old who had been recalled from retirement. With Lieutenant General Manfred von Richthofen's, great uncle of the flying ace, cavalry in the van, they were pushing southeast between Łódź and the Vistula. Part of Rennenkampf's First Army was finally moving east to attack the Germans. Their re-positioning was hindered when a makeshift bridge across the river collapsed, so they had to cross by ferry or on the nearest usable crossing 85 km (53 mi) upstream.[11] Once over they attacked the weakly defended side of the corridor extending south from the German frontier to their advancing spearhead. The Russians reoccupied Brzeziny, cutting the roads used by German XXV reserve corps, whose progress south was now blocked by the Russian Fifth Army. Sheffer was ordered to stop advancing, but the order did not reach him.[12] Suddenly it was the Germans who were ensnared in a pocket. Mackensen stopped attacking toward Łódź, turning to help to extricate them. The ecstatic Russians ordered trains for up to 20,000 prisoners, actually the German fighting strength in the pocket was about 11,000, but there were also 3,000 wounded. Other sources state that 50,000 prisoners were anticipated.[13]

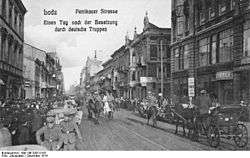

Hindenburg was alarmed by the intercepted wireless messages ordering the trains, but Mackensen assured him that they would prevail. In the pocket Richthofen's cavalry, which had been leading the advance, reversed direction to screen the rear of three infantry columns Sheffer formed along the roads for the retreat back northwest. The frozen, hungry Germans pushed on through the icy night. They reached the outskirts of Breziny unobserved, because most of the 6th Siberian Division were huddling in their sleeping quarters, trying to keep from freezing. The Germans attacked at dawn with bayonets on unloaded rifles and occupied much of the town before a shot was fired. The commander of 6th Siberian Division broke down. Swamped with conflicting accounts of German movements, and with the weather too foggy and days too short for aerial observation, Ruzsky issued a series of orders, each contradicting the one before.[14] He focused on preventing further German moves south instead of their thrust to the north. On 26 November XXV Reserve Corps broke out of the pocket, bringing with them 12,000 prisoners, some taken during the breakout, who pulled 64 captured guns. Inconclusive fighting continued until 29 November when at a conference with his front commanders Grand Duke Nicholas ordered his forces in Poland to withdraw to defensible lines nearer to Warsaw. Hindenburg learned from an intercepted wireless that Łódź was to be evacuated. The Germans moved in on 6 December, occupying a major industrial city with a population of more than 500,000 (about 70% of the population of Warsaw). German casualties were 35,000, while Russian losses were 70,000 plus 25,000 prisoners and 79 guns.[15]

Hindenburg summed it up: "In its rapid changes from attack to defense, enveloping to being enveloped, breaking through to being broken through, this struggle reveals a most confusing picture on both sides. A picture which in its mounting ferocity exceeded all the battles that had previously been fought on the Eastern front!" [16] The Polish winter bought a lull to the major fighting. A Russian invasion of Silesia must wait for spring. By this time the Russians feared the German army, which seemed to appear from nowhere and to win despite substantial odds against them, while the Germans regarded the Russian army with "increasing disdain." [17] Hindenburg and Ludendorff were convinced that if sufficient troops were transferred from the Western Front they could force the Russians out of the war.[18]

Sources

- Tucker, Spencer The Great War: 1914–18 (1998)

- ↑ Geoffrey Jukes,Peter Simkins,Michael Hickey, 2001, p. 28

- ↑ Geoffrey Jukes,Peter Simkins,Michael Hickey, The First World War: The Eastern Front, 1914-1918, 2002, p. 28

- ↑ Alan D. Axelrod, 2001, p. 108

- ↑ Alan D. Axelrod, The Complete Idiot's Guide to World War I, 2001, p. 108

- ↑ Hindenburg, Paul von (1921). Out of my life. London: F. A. Holt. p. vol. I 157.

- ↑ Buttar, Prit (2014). Collision of empires. The war on the Eastern Front in 1914. Oxford: Osprey Press. p. 361.

- ↑ 6 Weltkrieg 459 ff.

- ↑ 6 Weltkrieg 459 ff.; Корольков Г.К., Лодзинская операция 2 ноября - 19 декабря 1914 г. М. 1934, Приложение 2, 3 [Korol'kov GK Lodz operation November 2 - December 19, 1914 (Moscow, 1934)], Annexes 2 & 3; available at: http://www.grwar.ru/library/Korolkoff-Lodz/LO_11.html

- ↑ Buttar 2014, pp. 356-378

- ↑ Gilbert, Martin (1994). The First World War: A Complete History. New York: Henry Holt and Company. p. 107. ISBN 080501540X.

- ↑ Stone, Norman (1998) [1971]. The Eastern Front 1914-1917. London: Penguin. p. 104.

- ↑ Strachan, Hew (2001). The First World War. Volume I. To Arms. Oxford University Press. pp. 365–371.

- ↑ Strachan 2001, p. 370.

- ↑ Golovine, Nicholas N (1931). The Russian army in the World War. Oxford. p. 215.

- ↑ Gray, Randall; Argyle, Christopher (1990). Chronicle of the First World War. New York: Oxford. p. vol. I, 282.

- ↑ Hindenburg 1921, vol 1 p. 157.

- ↑ Buttar 2014 p. 387.

- ↑ Hindenburg 1921, vol. 1 pp.164-166.

Further reading

- Buttar, Prit. Collision of Empires: The War on the Eastern Front in 1914. Oxford: Osprey Publishing, 2014. ISBN 1782006486 OCLC 858956311

- Wulffen, Karl von, and P. B. Harm. The Battle of Lodz. Washington, D.C.: s.n., 1932. OCLC 36175892