Bathampton Down

| Bathampton Down | |

|---|---|

|

Footpath on Bathampton Down | |

| Location | Bathampton, Somerset County, England |

| Coordinates | 51°23′05″N 2°19′34″W / 51.3847°N 2.3262°WCoordinates: 51°23′05″N 2°19′34″W / 51.3847°N 2.3262°W |

| Area | 15 acres (6.1 ha) |

| Built | Bronze Age – Iron Age |

| Official name: Bathampton Camp | |

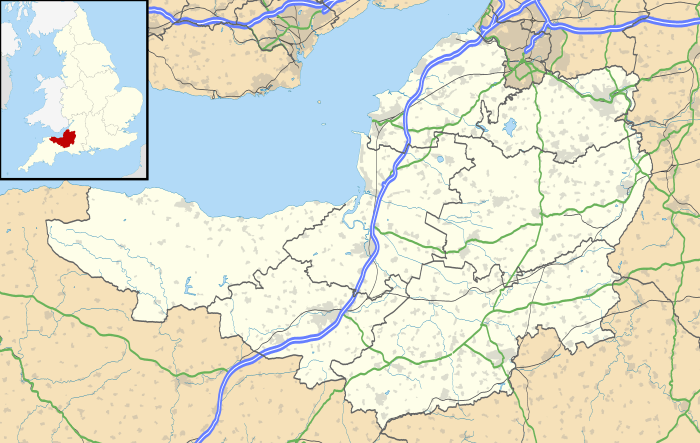

Location of Bathampton Down in Somerset | |

Bathampton Down, is a flat limestone plateau in Bathampton overlooking Bath, in Somerset near the River Avon, England.

There is evidence of man's activity at the site since the Mesolithic period including Bathampton Camp, an Iron Age hillfort or stock enclosure. It has also been used for quarrying and is now used for a golf course.

Geography

The plateau is formed from the Greater Oolitic Limestone with formations including Forest Marble, Bath Oolite, Twinhoe Beds and Combe Down Oolite.[1] The limestone dates from the Middle Jurassic with deposits of flint quartz and sandstone, mainly preserved in fissures or other cavities dating from the Middle Pleistocene.[2][3] The limestone is porous which, along with the flat nature of the plateau means there are no streams or rivers, particularly as several cold springs on Bathampton Down were diverted into reservoirs in the late 18th and early 19th centuries having originally flowed down to the River Avon.[4]

The southern area merges with Claverton Down and lies above part of the Combe Down and Bathampton Down Mines Site of Special Scientific Interest, designated because of the Greater and Lesser Horseshoe bat population.[5] There are small disused quarries which used to obtain Bath stone between the Roman era and the 18th century.[6] Several of these can be seen on the golf course and other have left workings which run under the fairways. The entrance to the Seven Sister's Quarry was blown up in the 1960s, although the remains of the tramway used to carry stone down to the Canal can still be seen.[7]

At the highest point is a Triangulation station at a height of 204 metres (669 ft) above sea level,[8][9] which provides views over the city and surrounding countryside.

The northern slopes between Bathampton Down and the River Avon have been built on and are traversed by the A36. To the east is Bathampton Wood separating the plateau from the road, River Avon, Kennet and Avon Canal and the Great Western Main Line. "Bathampton Rocks", an outcrop of rock was the site of the Bathampton Patrol (Auxiliary Units) Operational Base during the Second World War.[10] To the south and east are Claverton Down and the site of the University of Bath.

History

Prehistoric

The first evidence of human activity is from the Mesolithic period and consist of a dispersed collection of flint finds,[3] including hammerstones, cores, fragments of axes and arrowheads.[11] The remains of a stone circle were described in the 19th century, however no evidence remains.[12]

Four Bronze Age round barrows (tumuli) have been reported. There are also tentative findings of a probable bowl barrow and a possible confluent barrow. In one round barrow a small burial urn was recovered.[3] Many of the barrows were opened by John Skinner in the 18th Century.[13]

Hill forts developed in the Late Bronze and Early Iron Age, roughly the start of the first millennium BC.[14] The reason for their emergence in Britain, and their purpose, has been a subject of debate. It has been argued that they could have been military sites constructed in response to invasion from continental Europe, sites built by invaders, or a military reaction to social tensions caused by an increasing population and consequent pressure on agriculture. The dominant view since 1960s has been that the increasing use of iron led to social changes in Britain. Deposits of iron ore were located in different places to the tin and copper ore necessary to make bronze, and as a result trading patterns shifted and the old elites lost their economic and social status. Power passed into the hands of a new group of people.[15] Archaeologist Barry Cunliffe believes that population increase still played a role and has stated "[the forts] provided defensive possibilities for the community at those times when the stress [of an increasing population] burst out into open warfare. But I wouldn't see them as having been built because there was a state of war. They would be functional as defensive strongholds when there were tensions and undoubtedly some of them were attacked and destroyed, but this was not the only, or even the most significant, factor in their construction".[16]

Bathampton Camp may have been a univallate Iron Age hill fort or stock enclosure. The rectangular enclosure which is approximately 650 metres (2,133 ft) (east-west) by 500 metres (1,640 ft) (north-south) has been identified which may be a Medieval earthwork. The eastern side needs no protection, because the ground falls away steeply to the River Avon, 170 metres (558 ft) below. There is a single rampart and flat-bottomed ditch on the other three sides (univallate).

The site was excavated in 1904-5 and in 1952-4. Results found human and animal remains, pottery and flint flakes. Small fragments of pottery were found during excavations in the 1960s which have been dated to the Late Bronze Age or Early Iron Age.[17] The area is a Scheduled monument.[18]

During the Iron Age the area surrounding the camp had a settled agrarian landscape.[3] There are a network of Celtic fields of around 0.4 hectares (0.99 acres) around the area now covered by the golf course. These are difficult to date but thought to originate in the Iron Age and may have still be in use into the Roman Empire era.[19] The area to the south east, which is known as Bushey Norwood and includes part of the ramparts and some surviving upright stones, was given to the National Trust by Miss M.E. Mallett in 1960.[20]

Roman

There is some evidence of a small Roman villa, although the area is more noted for funerary activity with two Romano-British stone coffins being found in 1794 and 1824, both containing inhumation remains.[3]

Medieval

For many years it was thought that the earthworks were a part of the Wansdyke, but it now is thought improbable that Wansdyke crossed Bathampton Down.[21][22] There is stronger evidence of agrarian activity with extant strip lynchets to the west of Bathwick Wood. There are also several pillow mounds, used as artificial rabbit warrens in the area known as Bathampton Warren.[3][23] These date from 1256 when Henry III gave the right to hunt small game to the Bishop of Bath and Wells.[24]

Bathampton Down is one of the sites which are considered as possible locations for the Battle of Mons Badonicus, traditional site for legendary King Arthur's decisive victory over the Saxons.[25]

Modern

Sham Castle, a folly on the western edge of Bathampton Warren, was probably designed around 1755 by Sanderson Miller and built in 1762, by Richard James, master mason for Ralph Allen, "to improve the prospect" from Ralph Allen's town house in Bath.[26] It is a Grade II* listed building. It is a screen wall with a central pointed arch flanked by two 3-storey circular turrets, which extend sideways to a 2-storey square tower at each end of the wall.[27] Sham Castle is now illuminated at night.[28] There is a telecommunications mast near to Sham Castle.

Around 1730, at the North-East corner of Bathampton Camp, a new limestone quarry was opened by Ralph Allen, providing local cut Bath stone for many of the buildings in Bath. Its use declined by the end of the 18th Century, however between around 1800 and 1895 it was reopened to supply stone for the Kennet and Avon Canal,[29] with the stone being lowered down an inclined plane to the water.[30]

On the southern slopes is the American Museum in Britain[31] in a house, "Claverton Manor" designed by Jeffry Wyattville and built in 1820s[32] on the site of a manor bought by Ralph Allen in 1758.[28] It is now a Grade I listed building.[33] The American Museum in Britain was founded by two antique collectors, an American, Dallas Pratt, (21 August 1914 – 20 May 1994), (Pratt lived 30 years longer than his friend Judkyn, and wrote some recollections/memoirs about him)[34] and a Briton, John Judkyn, (b. 1913 – 27 July 1963)[35] and opened to the public for the first time on 1 July 1961. The garden is set into the valley of the River Avon and has views over the valley and the Kennet and Avon Canal and the Great Western Main Line for the Great Western Railway which follow the contour of the river. The American Museum employed Lanning Roper to design a mixed border. There is a Colonial Herb Garden and a "Mount Vernon Garden", which is a re-creation of U.S. first President George Washington's garden at his long-time family estate of Mount Vernon on the south bank of the Potomac River, near Alexandria, Virginia. The Arboretum has a collection of American trees.[32]

A drinking water reservoir was constructed in 1955,[2] although the land had originally been purchased by the City Council of Bath in 1928.[6]

The area is now part of a golf course behind the University of Bath. Construction of the campus began in 1964, with the first building, now known as "4 South", completed in 1965, and an artificial lake was constructed. Over the subsequent decade, new buildings were added as the campus took shape. The eastern part of the campus is dominated by the "Sports Training Village", built in 1992 and enhanced in 2003 with an extension. A proposal to move the boundary of the "Green Belt" surrounding the town from where it crosses the campus to its edge, to facilitate further development area for the University, was agreed in October 2007, by the local council for Bath and North East Somerset following a public inquiry. Over several years, the Bath University grounds have received recognition for their outstanding beauty with awards from groups like "Bath in Bloom".[36]

See also

References

- ↑ "Area 19: Bathampton Down and Claverton Down". Bath city wide character appriasal. Bath and North East Somerset Council. Archived from the original on 27 March 2012. Retrieved 29 May 2011.

- 1 2 Donovan, D.T. (1995). "High levels drift deposits east of Bath" (PDF). Proceedings of the University of Bristol Spelæological Society. 20 (2): 109–126. Retrieved 29 May 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Wessex Archaeology. "Archaeological Desk- based Assessment" (PDF). University Of Bath, Masterplan Development Proposal 2008. Bath University. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 September 2011.

- ↑ "7.18 Area 18: Entry Hill, Perrymead and Prior Park". Bath city wide character appriasal. Bath and North East Somerset Council. Archived from the original on 27 March 2012. Retrieved 29 May 2011.

- ↑ "Combe Down and Bathampton Down Mines" (PDF). SSSI Citation Sheet. English Nature. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 May 2011. Retrieved 29 May 2011.

- 1 2 "History". Bath Golf Club. Retrieved 29 May 2011.

- ↑ "Quarry locations". A concise history of Bath stone quarrying. D. Hawkins. Retrieved 29 May 2011.

- ↑ "Area 16 Cotswolds Plateaux and Valleys". Rural Landscapes. Bath and North East Somerset Council. Archived from the original on 27 March 2012. Retrieved 29 May 2011.

- ↑ Bristol & Bath No 172 (Map) (C3 ed.). 1:50,000. Ordnance Survey. 2008. ISBN 978-0-319-22914-9. Retrieved 16 March 2009.

- ↑ "Bathampton Patrol". Retrieved 21 November 2007.

- ↑ "Monument No. 204162". Pastscape National Monuments Record. English Heritage. Archived from the original on 4 May 2015. Retrieved 29 May 2011.

- ↑ Thomas, Rod (2008). A Sacred landscape: The prehistory of Bathampton Down. Bath: Millstream Books. p. 17. ISBN 978-0-948975-86-8.

- ↑ Thomas, Rod (2008). A Sacred landscape: The prehistory of Bathampton Down. Bath: Millstream Books. p. 21. ISBN 978-0-948975-86-8.

- ↑ Payne, Andrew; Corney, Mark; Cunliffe, Barry (2007), The Wessex Hillforts Project: Extensive Survey of Hillfort Interiors in Central Southern England, English Heritage, p. 1, ISBN 978-1-873592-85-4

- ↑ Sharples, Niall M (1991), English Heritage Book of Maiden Castle, London: B. T. Batsford, pp. 71–72, ISBN 0-7134-6083-0

- ↑ Time Team: Swords, skulls and strongholds, Channel 4, 19 May 2008, retrieved 16 September 2009

- ↑ Thomas, Rod (2008). A Sacred landscape: The prehistory of Bathampton Down. Bath: Millstream Books. pp. 46–48. ISBN 978-0-948975-86-8.

- ↑ "Bathampton Camp". Pastscape National Monuments Record. English Heritage. Archived from the original on 4 May 2015. Retrieved 10 May 2011.

- ↑ Thomas, Rod (2008). A Sacred landscape: The prehistory of Bathampton Down. Bath: Millstream Books. pp. 34–42. ISBN 978-0-948975-86-8.

- ↑ Archaeological Properties in the County of Somerset. National Trust. 1971.

- ↑ "Directions to West Wansdyke, Section 4". Wansdyke. Retrieved 15 March 2008.

- ↑ Thomas, Rod (2008). A Sacred landscape: The prehistory of Bathampton Down. Bath: Millstream Books. pp. 54–55. ISBN 978-0-948975-86-8.

- ↑ "MONUMENT NO. 203247". Pastscape National Monuments Record. English Heritage. Archived from the original on 3 October 2012. Retrieved 29 May 2011.

- ↑ Thomas, Rod (2008). A Sacred landscape: The prehistory of Bathampton Down. Bath: Millstream Books. pp. 56–57. ISBN 978-0-948975-86-8.

- ↑ Scott, Shane (1995). The hidden places of Somerset. Aldermaston: Travel Publishing Ltd. p. 16. ISBN 1-902007-01-8.

- ↑ Dunning, Robert (1995). Somerset Castles. Tiverton: Somerset Books. p. 77. ISBN 0-86183-278-7.

- ↑ "Sham Castle". Images of England. Retrieved 13 March 2008.

- 1 2 Scott, Shane (1995). The hidden places of Somerset. Aldermaston: Travel Publishing Ltd. pp. 16–17. ISBN 1-902007-01-8.

- ↑ "Bathampton Down Limestone Quarry". Pastscape National Monuments Record. English Heritage. Archived from the original on 3 October 2012. Retrieved 29 May 2011.

- ↑ "Monument No. 203359". Pastscape National Monuments Record. English Heritage. Archived from the original on 3 October 2012. Retrieved 29 May 2011.

- ↑ American Museum in Britain website

- 1 2 "Claverton Manor Garden". Garden Visit website. Archived from the original on 29 August 2008. Retrieved 29 May 2011.

- ↑ "Claverton Manor (The American Museum)". Images of England. Retrieved 16 December 2006.

- ↑ "Biographical notes on Dallas Pratt". Freshford Village. Archived from the original on 11 July 2011. Retrieved 29 May 2011.

- ↑ "Personal recollections of John Judkyn by Dallas Pratt". Freshford Village. Archived from the original on 11 July 2011. Retrieved 29 May 2011.

- ↑ "Bath in Bloom Competition". BANES Council. Archived from the original on 3 May 2008. Retrieved 14 October 2008.