Karo people (Indonesia)

|

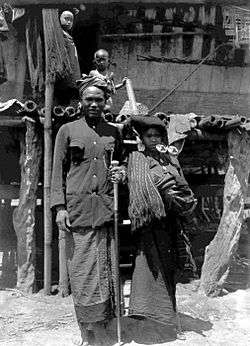

The woman is wearing a cloth called Gatip Ampar over her shoulder and silver padung (earrings), padungpadung. The man is wearing possibly a Julu berjongkit or a Ragi Santik as a hip covering. From Karo Regency, circa 1914-1919. | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 1,882,000 | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Karo Regency, Medan, Deli Serdang Regency, Langkat Regency | |

| Languages | |

| Batak Karo language | |

| Religion | |

| |

| Related ethnic groups | |

The Karo, or Karonese, are a people of the 'tanah Karo' (Karo lands) of North Sumatra and a small part of neighboring Aceh. The Karo lands consist of Karo Regency, plus neighboring areas in East Aceh Regency, Langkat Regency, Dairi Regency, Simalungun Regency and Deli Serdang Regency.[1] In addition, the cities of Binjai and Medan, both bordered by Deli Serdang Regency, contain significant Karo populations, particularly in the Padang Bulan area of Medan. The town of Sibolangit, Deli Serdang Regency in the foothills on the road from Medan to Berastagi is also a significant Karo town.

Karoland contains two major volcanoes, Mount Sinabung, which erupted after 400 years of dormancy in 2010, and Mount Sibayak. Karoland consists of the cooler high lands, and the upper and lower lowlands.

The Karolands were conquered by the Dutch in 1906, and in 1909 roads to the highlands were constructed, ending the isolation of the highland Karo people. The road linked Medan and the lowlands to Kabanjahe and from there to both Kutacane in Aceh and Pematangsiantar in Simalungun.

In 1911, an agricultural project began at Berastagi, now the major town in Karoland, to grow European vegetables in the cooler temperatures. Berastagi is today the most prosperous part of Karoland, just one hour from Medan, while towns further in the interior suffer from lower incomes and limited access to healthcare.[1]

The administrative centre of Karo Regency is Kabanjahe.

Karo Identity

The Karo people speak the Karo language, a language related to, but not mutually intelligible with, other Batak languages, in addition to Indonesian. These Karo people are divided up into clans or Merga. The Karo Merga are Ginting, Karo-Karo, Perangin-Angin, Sembiring and Tarigan, these Merga are then divided up into families.

Karo people religion are mostly Christian, a religion brought to Sumatra in the 19th Century by missionaries, but an increasing number living away from the Karo Highlands have converted to Islam, with the influence of Muslim Javanese and Malay peoples making the traditional habits of pig farming and cooking less common. Some Muslims and Christians however still retain their traditional animist beliefs in ghosts, spirits (perbegu), and traditional jungle medicine, despite that fact it contradicts their other beliefs.

Karo people traditionally lived in shared longhouses, but very few now remain, and new construction is exclusively of modern designs.

It is believed that Karo people may have migrated from the other lands in order to take part in trade with the visiting Tamils. This intercourse had an influence on their religious beliefs, as well as ethnic makeup, the marga 'Sembiring', meaning 'black one', and many Sembiring sub-marga (Colia, Berahmana, Pandia, Meliala, Depari, Muham, Pelawi and Tekan) are clearly of South-Indian origin, suggesting that inter-marriage between Karo and Tamil people took place.[2]

Religion

Traditional Beliefs

Christianity

The Karo were harassing Dutch interests in East Sumatra, and Jacob Theodoor Cremer, a Dutch administrator, regarded evangelism as a means to suppress this activity. The Netherlands Missionary Society answered the call, commencing activities in the Karolands in 1890, where they engaged not only in evangelism, but also in ethnology and documenting the Karo culture. The missionaries attempted to construct a base in Kabanjahe in the Karo highlands, but were repelled by the suspicious locals.

In retaliation the Dutch administration waged a war to conquer the Karolands, as part of their final consolidation of power in the Indies. The Karo perceived Christianity as the 'Dutch religion', and its followers as 'dark-skinned Dutch'. In this context, the Karo church was initially unsuccessful, and by 1950 the church had only 5,000 members. In the years following Indonesian independence the perception of Christianity among the Karo as an emblem of colonialism faded, with the church itself acquiring independence, and adopting more elements of traditional Karo culture such as music (whereas previously the brass band was promoted). By 1965, the Karo church had grown to 35,000 members.[3]

After the Indonesian Genocide

Unlike the Toba Batak, who embraced Christianity fairly readily, the Karo continued to follow their traditional religion for several decades after the arrival of the first Christian missionaries in the Karolands.

Following the Indonesian Genocide in 1965–1966, at which time over 70% of the Karo still followed traditional religions, there was a push for Indonesians to identify with an established religion. Many Karo joined the GBKP (Batak Karo Protestant church) (60,000 were baptised in 1966–1970.[4]), and from 5,000 Muslims (mostly non-Karo) in Karoland in 1950, there were 30,000 in 1970.

At this time, the Balai Pustaka Adat Merga Si Lima (BPAMSL) was established in Berastagi. BPAMSL, proclaimed the 'agama Pemena', or the religion (agama) of the founders (Pemena).

The concept of 'religion' was relatively new in the Karoland; historically the neighbouring Muslim people, were known as 'kalak Jawi' or the people of the Jawi lands, and the concept of 'kalak Kristen', or Christian people, was the first time that people were identified by their religion rather than their land. The 'agama Pemena' of BPAMSL was a defence against accusations of atheism, Communism or animism.

BPAMSL conducted a ceremony in the Lau Debuk–Debuk hot spring akin to the one to invest a new Karo village. This ceremony essentially validated the Dutch-established Berastagi as a 'true' Karo village, and was attended by the regent of Karo regency and other political figures.

At that time, BPAMSL became the largest religious organisation in the Karolands, surpassing the GBKP, and absorbing many who had joined it following the anti-Communist purge.

As a response to the Pemena movement, the GBKP after 1969 determined that members could participate in village rituals as a matter of adat (tradition), whereas previously they had been rejected by GBKP as of a religious (unchristian) nature.

After Golkar won the elections in 1972, Djamin Ginting, a leading BPAMSL figure proclaimed BPAMSL as a movement within Golkar, adopting Islam as his religion, while Indonesian National Party supporters rejected this. With BPAMSL no longer a united force for the practice of Pemena, and Pemena itself no longer a uniting force in the Karoland, and with all Indonesians required to follow one of the religions of Islam, Protestantism, Catholicism, Hinduism and Buddhism, or risk writing 'without belief' on their identity card, the board members of BPAMSL met with a wealthy Indian man from Medan and determined that the traditional religion was in fact an expression of Indian Hinduism, and that it had been founded by a 'Bagavan Bṛgu', from which had been derived the alternate name for the Karo beliefs 'Perbegu' (followers of 'begu' (in Karo, begu is a spirit or ghost)), the existence of Indian-originating Karo marga names and similarities between Karo ritual and Indian Hindu ones all proving this. Thus the Association of Karo Hinduism (PAHK) was proclaimed.

The PAHK declared 'Pemena is the same as Hinduism' and received funding from Medan Indians for their cause. PAHK became a movement within Parisada Hindu Dharma Indonesia, and as a culmination of this, in 1985 PAHK became a branch of the PHDI, PHDK. When Parisada Hindu Dharma Karo (PHDK) was established, it claimed 50,000 members, and 50,000 more sympathisers. The PHD built a Balinese-style temple in Tanjung, a Karo village to inaugurate the PHDK. In doing so it was stated that PHDI (i.e. Balinese) Hinduism was the only valid form, and in fact the Karo 'Hindu' ritual were invalid, the name change from 'Hindu Karo' to 'Hindu Dharma Karo' and the replacement of Tamil Indians on the PAHK board with Balinese on the PHDK symbolising the assertion of 'Hindu Dharma' as the 'valid' Hindu religion, with little regard paid to re-imagining Karo rituals within an Agama Hindu context.

There was an immediate decline in PAHK/PHDK support, with a small number of people still following the PHDK practices, but others following traditional Karo (Pemena) rituals outside of the formal context of PHDK. This left the Christian GBKP, by then for many years an indigenous Karo-run adat-respecting church a rather more comfortable option for most Karo than the Balinese Hinduism asserted by PHDK. There are today four Balinese-style PHDK temples in the Karoland, but the concept of Karo traditional beliefs as a manifestation of Hinduism is otherwise largely extinct.[5]

Modern Christianity

Although the Gereja Batak Karo Protestan (GBKP) is the largest Karo church, with has 276,000 members (as of 2006) in 398 congregations with 196 pastors,[6] there are also Catholic (33,000 members as of 1986) and several Pentecostalist denominations.

Merga Si Lima

Karo people belong to one of five marga or clans, which are Ginting, Karo-Karo, Perangin-Angin, Sembiring and Tarigan. Each marga is further divided into sub-marga (83 in total). With the exception of marga Karo-Karo, most Karo identify themselves by their principal rather than sub-marga.

Karo and Batak adat prohibits marriage within a marga (e.g., Ginting with Ginting). Upon marriage, the bride becomes a part of the groom's family, with the kalimbubu (bride's family) joining with anakberu (groom's family).

Karonese marriages are very large affairs, with typically 200 attendees, comprising the numerous family members of both marrying parties, comprising a number of elements, including the chewing of betel nut (sirih), traditional Karonese dancing (which focuses on hand movements), the payment of a nominal dowry to each of the kalimbubu. Food is cooked by the anakberu, who will spend many hours cooking vast quantities to cater for the numerous guests. This social obligation is expected to be reciprocated, so that Karonese people can attend several weddings each month. Non-Karo people do not attend the wedding ceremony, although such friends might be invited to a separate party in the evening. Where a non-Karonese person wishes to marry a Karonese, they would be adopted into a Karo marga.

Traditionally kalimbubu-anakberu relationships would be reinforced by cross-cousin marriages (i.e. to one's mother's brother's child), however in modern Karo society this tradition is no longer important.[1]

Marga Origin Mythology

Karo tradition states that the Merga si Lima originate from five villages, each established by a Sibayak, a founding community. The Sibayak of Suka whose family name was Ginting Suka established the village of Suka. The Sibayak of Lingga called Karo-karo Sinulingga established the village of Lingga. The Sibayak of Barusjahe whose family name was Karo-karo Barus pioneered the village of Barusjahe. The Sibayak of Sarinembah, called Sembiring Meliala established the village of Sarinembah. The Sibayak of Kutabuluh named Perangin-angin established the village of Kutabuluh.

Each one of these five villages has its own satellite villages inhabited by the extended families of the main village inhabitants. The satellite villages were established for the convenience of the villagers whose fields were relatively far from the main villages. The purpose was to save them time when travelling back and forth from the village to their fields. Today, these satellite villages have developed and matured to be independent of the main villages. In the old times, these satellite villages used to ask for help from the main villages to deal with natural disasters, tribal disputes, diseases and famine.

The leaders of these satellite villages were called URUNGs. The Sibayak of Lingga administered five villages i.e., Tiganderket, Tiga Pancur, Naman, Lingga and Batukarang. The Sibayak of Suka administered four villages i.e., Suka, Seberaya, Ajinembah and Tengging. The Sibayak of Sarinembah administered four villages i.e., Sarinembah, Perbesi, Juhar and Kutabangun. The Sibayak of Barusjahe administered two villages i.e., Barusjahe and Sukanalu. The Sibayak of Kutabuluh administered two villages i.e., Kutabuluh and Marding-ding.

Cuisine

Foods

- Babi Panggang Karo (BPK) (Grilled Pork With pig Blood Sauce).[7]

- Gulai ikan (a fish curry).

- Lemang-lemang (A chicken soup).

- Rendang (spicy meat dish).

- Lomok-lomok (traditional spicy or savoury dish made with pork or dog).

- Arsik/tangas-tangas (a traditional goldfish/carp dish).

- Pagit-pagit atau Terites (traditional Karo soup made from partially digested grass from a cow, mixed with other ingredients, herbs and spices).

- Cimpa (various Karo cakes made of rice flour, coconut and palm sugar. Traditionally consumed during the Kerja Tahun (Yearly Party) festival).[8]

- Tasak telu (a traditional Karo chicken dish which is cooked three times using different ingredients and cooking methods each time).

- Rires (more commonly known as "Lemang", a traditional food made of glutinous rice and coconut milk).

- Cimpa Bohan (various Karo cakes made of purple sweet potato, coconut and palm sugar. Traditionally consumed during the Kerja Tahun (Yearly Party) festival).

- Cipera (a type of Karo soup made with Corn, chicken and other spices and left to stew in water).

Drinks

- Bandrek (a traditional ginger tea with other spices).

References

- 1 2 3 http://faculty.washington.edu/kushnick/karo_biblio_v1.2.pdf

- ↑ "Deze domeinnaam is via de veiling van DomainOrder.nl geregistreerd".

- ↑ History of Christianity in Indonesia. pp. 569-584

- ↑ History of Christianity in Indonesia p576

- ↑ Hinduism in Modern Indonesia. Chapter 13. Juara Ginting

- ↑ http://www.oikoumene.org/ru/member-churches/regions/asia/indonesia/karo-batak-protestant-church.html

- ↑ Sri Devi Valentina Simamora (2 December 2015). "5 Makanan Khas Batak Paling Dirindukan Anak Rantau". Liputan6. Retrieved 2016-11-06.

- ↑ "Cimpa, Kuliner HUT Kemerdekaan Indonesia Khas Karo". JPNN. 18 August 2016. Retrieved 2016-11-06.

Further reading

- Masri Singarimbun (1975), Kinship, Descent, and Alliance Among the Karo Batak, University of California Press, ISBN 0-5200-2692-6

- Roberto Bangun (2006), Mengenal Suku Karo, Yayasan Pendidikan Bangun, OCLC 115901224

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Batak Karo people. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Culture of Batak Karo people. |