Basque conflict

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

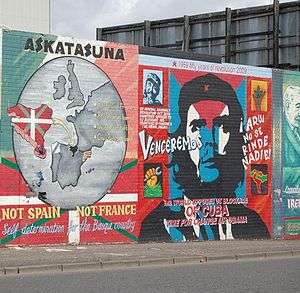

The Basque conflict, also known as the Spain–ETA conflict, was an armed and political conflict between Spain and the Basque National Liberation Movement, a group of social and political Basque organizations which sought independence from Spain and France. The movement was built around the separatist organization ETA[5][6] which since 1959 launched a campaign of attacks against Spanish administrations. In response, ETA was proscribed as a terrorist organization by the Spanish, British,[7] French[8] and American[9] authorities. The conflict took place mostly on Spanish soil, although to a smaller degree it was also present in France, which was primarily used as a safe haven by ETA members. It was the longest running violent conflict in modern Western Europe.[10] It has been sometimes referred to as "Europe's longest war".[11]

The terminology is controversial.[12] "Basque conflict" is preferred by Basque nationalist groups, including those opposed to ETA violence.[13] Spanish public opinion generally rejects the term, seeing it as legitimate state agencies fighting a terrorist group.[13]

The conflict has both political and military dimensions. Its participants include politicians and political activists on both sides, the abertzale left and the Spanish government, and the security forces of Spain and France fighting against ETA and other small organizations, usually involved in the kale borroka. Far-right paramilitary groups fighting against ETA were also active in the 1970s and 1980s.

Although the debate on Basque independence started in the 19th century, the armed conflict did not start until ETA was created. Since then, the conflict has resulted in the death of more than 1,000 people, including police and security officers, members of the armed forces, Spanish politicians, journalists and civilians, and some ETA members. There have also been thousands of people injured, dozens kidnapped and a disputed number has gone to exile either to flee from the violence or to avoid capture by Spanish or French police or by Europol / Interpol.[3][14]

On 20 October 2011, ETA announced a "definitive cessation of its armed activity".[15][16] Spanish premier Jose Luis Rodriguez Zapatero described the move as "a victory for democracy, law and reason".[16]

Definition of the conflict

The Basque conflict, is used to define either the broad political conflict between a part of Basque society and the initially Francoist and later Constitutional model of the Spanish decentralized state, to exclusively describe the armed confrontation between ETA and the Spanish state or to describe a mixture of both perspectives. France was not initially involved in the conflict with ETA nor was it ever targeted by the organization, only slowly beginning to cooperate with Spanish law enforcement in 1987. Unlike in Northern Ireland, the Spanish armed forces were never deployed nor were involved in the conflict although they represented one of ETA's major targets outside the Basque Country.

According to José Ramón Blázquez[17] "The Basque political Conflict is constituted by the legitimate claim of a big part of Basque society for a frame of sovereignty in face of the Unionist Spanish State model, resulting in an untenable situation for coexistence within a plural society to which the right to decide its own status is deprived, beyond the law inherited from a dictatorship, whose violence led to the emergence of ETA and with it the distortion of the problem and the blockade of its agreed solution." (original ES)

This idea has been rejected, for example, by José Maria Ruiz Soroa[18] and by the main constitutionalist Spanish parties, that have rejected the existence of a political conflict and refer only to the action of a terrorist organisation against the rule of law.[19] In 2012, Antonio Basagoiti, the head of the Basque branch of the People's Party admitted the existence of a Basque conflict, but stated that it was a political one between different entities in the Basque country.[20]

Amaiur Senator Urko Aiartza and Dr Julen Zabalo have written that "There is no unanimous agreement when it comes to determining the reasons for the so-called Basque conflict. According to different sources, it is either a long conflict with historical roots, an instrument of Basque nationalist politics, an attempt to impose a privilege, or evidence of the state's obstinacy. Whichever of these may be the case, an understanding of the historical relations between the Basque provinces and the Spanish and French states is indispensable in order to explain the present conflict."[21]

Background

The Basque Country (Basque: Euskal Herria) is the name given to the geographical area located on the shores of the Bay of Biscay and on the two sides of the western Pyrenees that spans the border between France and Spain. Nowadays, this area is fragmented into three political structures: the Basque autonomous community, also known as Euskadi, and Navarre in Spain, and three French provinces known as the Northern Basque Country. Approximately 3,000,000 people live in the Basque Country.

Basque people have managed to preserve their own identifying characteristics such as their own culture and language throughout the centuries and today a large part of the population shares a collective consciousness and a desire to be self-governed, either with further political autonomy or full independence. Over the centuries, the Basque Country has maintained various levels of political self-governance under different Spanish political frameworks. Nowadays, Euskadi enjoys the highest level of self-governance of any nonstate entity within the European Union.[22] However, tensions about the type of relationship the Basque territories should maintain with the Spanish authorities have existed since the origins of the Spanish state and in many cases have fuelled military confrontation, such as the Carlist Wars and the Spanish Civil War.

Following the 1936 coup d'état that overthrew the Spanish republican government, a civil war between Spanish nationalist and republican forces broke out. Nearly all Basque nationalist forces, led by the Basque Nationalist Party (PNV) sided with the Republic, even though Basque nationalists in Álava and Navarre fought along Basque Carlists on the side of Spanish nationalists. The war ended with the victory of the nationalist forces, with General Francisco Franco establishing a dictatorship that lasted for almost four decades. During Franco's dictatorship, Basque language and culture were banned, institutions and political organisations abolished (to a lesser degree in Alava and Navarre), and people killed, tortured and imprisoned for their political beliefs. Although repression in the Basque Country was considerably less violent than in other parts of Spain,[23] thousands of Basques were forced to go into exile, usually to Latin America or France.

Influenced by wars of national liberation such as the Algerian War or by conflicts such as the Cuban Revolution, and disappointed with the weak opposition of the PNV against Franco's regime, a young group of students formed ETA in 1959. It first started as an organization demanding the independence of the Basque Country, from a socialist position, and it soon started its armed campaign.

Timeline

1959–1979

ETA's first attacks were sometimes approved of by a part of the Spanish and Basque societies, who saw ETA and the fight for independence as a fight against the Franco administration. In 1970, several members of the organization were condemned to death in the Proceso de Burgos (Burgos Trial), although international pressure resulted in commutation of the death sentences.[24] ETA slowly became more active and powerful, and in 1973 the organisation was able to kill the president of the Government and possible successor of Franco, Luis Carrero Blanco. From that moment on, the regime became tougher in their struggle against ETA: many members died in shootouts with security forces and police carried out big raids, such as the arrest of hundreds of members of ETA in 1975, after the infiltration of a double agent inside the organisation.[25]

In mid-1975, a political bloc known as Koordinadora Abertzale Sozialista (KAS) was created by Basque nationalist organisations. Away from the PNV, the bloc comprised several organisations formed by people contrary to the right-wing Franco's regime and most of them had their origins in several factions of ETA, which was part of the bloc as well.[26] They also adopted the same ideology as the armed organisation, socialism. The creation of KAS would mean the beginning of the Basque National Liberation Movement.

In November 1975, Franco died and Spain started its transition to democracy. Many Basque activists and politicians returned from exile, although some Basque organizations were not legalized as had happened with other Spanish organizations.[27] On the other side, the death of Franco elevated Juan Carlos I to the throne, who chose Adolfo Suárez as Prime Minister of Spain. Following the approval of the Spanish constitution in 1978, a Statute of Autonomy was promulgated and approved in referendum. The Basque Country was organized as an Autonomous Community.

.jpg)

The new Spanish constitution had overwhelming support around Spain, with 88.5% voting in favour on a turnout of 67.1%. In the three provinces of the Basque Country, these figures were lower, with 70.2% voting in favour on a turnout of 44.7%. This was due to the call to abstention by EAJ-PNV and the creation of a coalition of Abertzale left organisations brought together to advocate for "no" in the referendum, as they felt that the constitution did not meet their demands for independence. The coalition was the beginning of the political party Herri Batasuna, which would become the main political front of the Basque National Liberation Movement. The coalition had its origins in another one made two years before, named Mesa de Alsasua.[27] ETA also felt that the constitution was unsatisfactory and intensified their armed campaign: 1978 to 1981 were ETA's bloodiest years with more than 230 people killed. At the same time, several far-right armed organisations fighting against ETA and its supporters were created, and at least 40 people were killed in attacks blamed on organisations such as the Batallón Vasco Español and Guerrilleros de Cristo Rey. Although not related to the Basque conflict, one of these organizations carried out the infamous 1977 Massacre of Atocha.

Also in the late 1970s, several Basque nationalist organizations, such as Iparretarrak, Hordago or Euskal Zuzentasuna, started to operate in the French Basque Country. An anarchist breakaway of ETA, Comandos Autónomos Anticapitalistas, also started carrying out attacks around the Basque Country. A similar but smaller organization to ETA, Terra Lliure, appeared demanding independence for the Catalan Countries. The Basque conflict had always had an influence on the Catalan society and politics, due to the similarities between Catalonia and the Basque Country.

1980–1999

During the process of electing Leopoldo Calvo-Sotelo as Spain's new president in February 1981, Civil Guards and army members broke into the Congress of Deputies and held all deputies at gunpoint. One of the reasons that led to the coup d'état was the increase of ETA's violence. The coup failed after the King called for the military powers to obey the Constitution. Days after the coup, ETA's faction politiko-militarra started its disbanding, with most of its members joining Euskadiko Ezkerra, a leftist nationalist party away from the Abertzale left. General elections were held in 1982, and Felipe González, from the Socialist Workers' Party became the new president, while Herri Batasuna won two seats. In the Basque Country, Carlos Garaikoetxea from the PNV became lehendakari in 1979. During those years, hundreds of members of Herri Batasuna were arrested, especially after some of them sang the Eusko Gudariak in front of Juan Carlos I.[27]

After Felipe González's victory, the Grupos Antiterroristas de Liberación (GAL), death squads established by officials belonging to the Spanish government, were created. Using state terrorism, the GAL carried out dozens of attacks around the Basque Country, killing 27 people. It targeted ETA and Herri Batasuna members, although sometimes civilians were also killed. The GAL were active from 1983 until 1987, a period referred to as the Spanish Dirty War.[28] ETA responded to the dirty war by intensifying its attacks: the organisations started carrying out massive car bomb attacks in Madrid and Barcelona, such as the Hipercor bombing, which killed 21 civilians. After the attack, most of the Spanish and Basque political parties signed many pacts against ETA, such as the Madrid pact or the Ajuria-Enea pact. It was during this time that Herri Batasuna got its best results: it was the most voted party in the Basque autonomous community for the European Parliament elections.[29]

While talks between the Spanish government and ETA had already taken place in the late 1970s and early 1980s, which had led to the dissolution of ETA (pm), it was not until 1989 that both sides held formal peace talks. In January, ETA announced a 60-day ceasefire, while negotiations between ETA and the government were taking place in Algiers. No successful conclusion was reached, and ETA resumed violence.[30]

After the end of the dirty war period, France agreed to cooperate with the Spanish authorities in the arrest and extradition of ETA members. These would often travel to and from between the two countries using France as a base for attacks and training. This cooperation reached its peak in 1992, with the arrest of all ETA leaders in the town of Bidart. The raid came months before the 1992 Olympic Games in Barcelona, with which ETA tried to gather worldwide attention with massive attacks around Catalonia.[31] After that, ETA announced a two-months ceasefire, while they restructured the whole organisation and created the kale borroka groups.[32]

In 1995, ETA tried to kill José María Aznar, who would become prime minister of Spain one year later, and Juan Carlos I. That same year, the organisation launched a peace proposal, which was refused by the government. On the following year, ETA announced a one-week ceasefire and tried to engage peace talks with the government, a proposal that was once again rejected by the new conservative government.[33] In 1997, young councillor Miguel Ángel Blanco was kidnapped and killed by the organisation. The killing produced a widespread rejection by Spanish and Basque societies, massive demonstrations and a loss of sympathisers, with even some ETA prisoners and members of Herri Batasuna condemning the killing.[34] That same year, the Spanish government arrested 23 leaders of Herri Batasuna for allegedly collaborating with ETA. After the arrest, the government started to investigate Herri Batasuna's ties with ETA, and the coalition changed its name to Euskal Herritarrok, with Arnaldo Otegi as their leader.[35]

In the 1998 Basque elections, the Abertzale left got its best results since the 1980s, and Euskal Herritarrok became the third main force in the Basque Country. This increase of support was due to the declaration of a ceasefire by ETA one month before the elections.[35] The ceasefire came after Herri Batasuna and several Basque organisations, such as the PNV, which at that time was part of the PP's government, reached a pact, named Lizarra pact, aimed at putting pressure on the Spanish government to make further concessions towards the independence. Influenced by the Northern Ireland peace process, ETA and the Spanish government engaged in peace talks, which ended in late 1999, after the government refused to discuss the armed organisation's demands for independence.[36]

2000–2009

In 2000, ETA resumed violence and intensified its attacks, especially against senior politicians, such as Ernest Lluch. At the same time, dozens of ETA members were arrested and the Abertzale left lost some of the support it had obtained in the 1998 elections. The breaking of the truce provoked Herri Batasuna's dissolution and its reformation into a new party called Batasuna. Following disagreements over the internal organization of the Batasuna, a group of people broke away to form a separate political party, Aralar, present mainly in Navarre.[37] In 2002, the Spanish government passed a law, named Ley de Partidos (Law of Parties), which allows the banning of any party that directly or indirectly condones terrorism or sympathises with a terrorist organisation. As ETA was considered a terrorist organisation and Batasuna did not condemn its actions, the government banned Batasuna in 2003. It was the first time since Franco's dictatorship that a political party had been banned in Spain.[38] That same year, Spanish authorities closed the only newspaper written fully in Basque, Egunkaria, and journalist were arrested, due to allegations of links with ETA which were dismissed by Spanish justice seven years later.[39] In 1998, another newspaper, Egin, had already been closed on similar grounds that were also dismissed by Spanish justice eleven years later.[40][41][42]

After the government falsely accused ETA of carrying out the 2004 Madrid train bombings, the conservative government lost the elections in favour of the Socialist Workers' Party, and José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero became the new president of Spain.[43] One of Zapatero's first actions was to engage in new peace talks with ETA. In mid-2006, the organisation declared a ceasefire, and conversations between Batasuna, ETA and the Basque and Spanish governments started. Despite the claims of peace talks ending in December, when ETA broke the truce with a massive car bomb at the Madrid-Barajas Airport, a new round of conversations took place on May 2007.[44] ETA officially ended the ceasefire in 2007, and resumed its attacks around Spain.[45] From that moment on, the Spanish government and police intensified their struggle both against ETA and the Abertzale left. Hundreds of members of the armed organisation were arrested since the end of the truce, with four of its leaders being arrested in less than one year. Meanwhile, the Spanish authorities banned more political parties such as Basque Nationalist Action,[46] Communist Party of the Basque Homelands or Demokrazia Hiru Milioi. Youth organisations such as Segi have been banned, while members of trade unions, such as Langile Abertzaleen Batzordeak have also been arrested.[47] In 2008, Falange y Tradición, a new Spanish far-right nationalist group appeared, carrying out dozens of attacks in the Basque Country. The organisation was dismantled in 2009.[48]

2010

In 2009 and 2010, ETA suffered even more blows to its organization and capacity, with more than 50 members arrested in the first half of 2010.[49] At the same time, the banned Abertzale left started to develop documents and meetings, where they committed to a "democratic process" that "must be developed in a complete absence of violence". Due to these demands, ETA announced in September that they were stopping their armed actions.[50]

2011

On 17 October, an international peace conference was held in Donostia-San Sebastián, aimed at promoting a resolution to the Basque conflict. It was organized by the Basque citizens' group Lokarri, and included leaders of Basque parties,[51] as well as six international personalities known for their work in the field of politics and pacification: Kofi Annan (former UN Secretary-General), Bertie Ahern (former Prime Minister of Ireland), Gro Harlem Brundtland (international leader in sustainable development and public health, former Prime Minister of Norway), Pierre Joxe (former Interior Minister of France), Gerry Adams (president of Sinn Féinn, member of the Irish Parliament) and Jonathan Powell (British diplomat who served as the first Downing Street Chief of Staff). Tony Blair – former Prime Minister of the United Kingdom – could not be present due to commitments in the Middle East,[52] but he supported the final declaration. The former US President Jimmy Carter (2002 Nobel Peace Prize) and the former US senator George J. Mitchell (former United States Special Envoy for Middle East Peace) also backed this declaration.[53]

The conference resulted in a five-point statement that included a plea for ETA to renounce any armed activities and to demand instead negotiations with the Spanish and French authorities to end the conflict.[51] It was seen as a possible prelude to the end of ETA's violent campaign for an independent Basque homeland.[54]

Three days later – on 20 October – ETA announced "definitive cessation of its armed activity".[15][16] They said they were ending their 43-year armed campaign for independence and called on Spain and France to open talks.[15] Spanish premier Jose Luis Rodriguez Zapatero described the move as "a victory for democracy, law and reason".[16]

2012

On 28 May 2012, ETA members Oroitz Gurruchaga and Xabier Aramburu were arrested in southern France.[55]

Casualties

Estimates of the total number of conflict-related deaths vary and are highly disputed. The number of deaths caused by ETA is consistent among different sources, such as the Spanish Interior Ministry, the Basque government, and most major news agencies. According to these sources, the number of deaths caused by ETA are 829. This list does not include Begoña Urroz, killed in 1960 when she was 22 months old. Although this killing has been attributed by the Spanish parliament's majority vote and main media to ETA for years, as held by the newspaper El País in 2013,[56] the attack was committed by the DRIL (Directorio Revolucionario Ibérico de Liberación).[57][58]

Some organizations such as the Colectivo de Víctimas del Terrorismo en el País Vasco raise the death toll of ETA's victims to 952. This is due to the inclusion to the list of several unresolved attacks such as the Hotel Corona de Aragón fire.[59] The Asociación de Víctimas del Terrorismo also includes the victims of the Corona de Aragón fire on its list of ETA's deaths.[60] Sources have suggested ETA responsibility in the crash of Iberia Airlines Flight 610 at Monte Oiz (Bilbao) on 19 February 1985 with 148 killed [61]

Regarding the Basque National Liberation Movement side, some sources such as the Euskal Memoria foundation list the number of deaths on their side as 474 in the period between 1960 and 2010. The count includes people killed by police forces, right-wing organizations, as well as people being killed while traveling to see their relatives in far away prisons, among other causes. News agency Eusko News states that at least 368 people have died on the Basque nationalist side. Most of the lists also include an undefined number of suicides caused by the conflict, coming from former ETA members, tortured people or policemen.

Responsibility

| Responsibility for killing | |

|---|---|

| Responsible party | No. |

| Euskadi Ta Askatasuna | 829[2] |

| Paramilitary and far-right groups | 72[3] |

| Spanish security forces | 169[3] |

| Other cases | 127[3] |

| Total | 1197 |

Status

| ETA deaths by status of victim[2] | |

|---|---|

| Status | No. |

| Civilian | 343 |

| Members of security forces | 486 |

| of whom: | |

| Guardia Civil | 203 |

| Cuerpo Nacional de Policía | 146 |

| Spanish Army | 98 |

| Policia Municipal | 24 |

| Ertzaintza | 13 |

| Mossos d'Esquadra | 1 |

| French National Police | 1 |

Prisoners

The Spanish and French law enforcement agencies have imprisoned many people for their connection to illegalized elements of the Basque National Liberation Movement. Most have been convicted of terrorist activities, or for belonging to ETA or organisations linked to it, or for "enaltecimiento del terrorismo"[62] which literally translates as "glorification of terrorism". The number of people incarcerated reached a peak of 762 in 2008.[63] These prisoners are jailed in prisons all over France and Spain "to make it difficult for ETA to communicate with them," according to non-revealed sources.[64][65]

For many Basque people this is one of the most emotive issues relating to Basque Nationalism. Demonstrations calling for their return to the Basque region often involve thousands of people.[66][67][68] Currently there is a highly publicised campaign calling for the return of these dispersed prisoners to the Basque Country. Its slogan is "Euskal presoak- Euskal Herrira" ("Basque prisoners- to the Basque Country").[69]

Some groups such as Etxerat have been calling for a general amnesty, similar to that which took place in Northern Ireland in 2000.[70] The Spanish government has so far rejected moves to treat all prisoners in the same way. Instead they opened the 'Via Nanclares' in 2009 which is a way for individual prisoners to get better conditions, and eventually gain limited release. It involves the individual asking for forgiveness, distancing themselves from ETA and paying compensation.[71]

See also

- Politics in the Basque Country

- List of conflicts in Europe

- International Contact Group (Basque politics)

- History of the Basque people

- The Troubles – Conflict in Northern Ireland

References

- ↑ Basque separatists ETA 'end armed struggle' – Europe – Al Jazeera English

- 1 2 3 4 "Últimas víctimas mortales de ETA: Cuadros estadísticos". Ministerio del Interior (in Spanish). Retrieved 5 December 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "Datos significativos del conflicto vasco, 1968–2003". Eusko News (in Spanish). 2003. Retrieved 1 November 2010.

- ↑ Carmena, Manuela; Landa, Jon Mirena; Múgica, Ramón; Uriarte, Juan Mº (2013), Euskal kasuan gertaturiko giza eskubideen urraketei buruzko oinarrizko txostena (1960-2013), Eusko Jaurlaritza.

- ↑ "European Union list of terrorist organizations" (PDF). Official Journal of the European Union. 2006. Retrieved 1 November 2010.

- ↑ "Foreign Terrorist Organizations". Office of the Coordinator for Counterterrorism. 15 October 2010. Archived from the original on 28 October 2010. Retrieved 1 November 2010.

- ↑ Proscribed terrorist groups

- ↑ (French) French list of terrorist organizations, in the annex of Chapter XIV

- ↑ Foreign Terrorist Organizations (FTOs). Retrieved on 16 April 2013.

- ↑ "The Basque Conflict: New ideas and Prospects for Peace" (PDF). Gorka Espiau Idoiaga. April 2006. Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 October 2010. Retrieved 1 November 2010.

- ↑ "Eyewitness: ETA's shadowy leaders". news.bbc.co.uk. 2 December 1999. Retrieved 1 November 2010.

- ↑ "El 'Basque conflict', para Wikipedia". El Mundo. 2 December 2013. Retrieved 7 January 2014.

- 1 2 "More Basque Violence". New York Times. 3 August 2009. Retrieved 7 January 2014.

- ↑ "El Foro de Ermua culpa a Ibarretxe del exilio forzoso de 119.000 vascos". El Mundo. 26 February 2005. Retrieved 1 November 2010..

- 1 2 3 "Armed group ETA announces 'definitive cessation of its armed activity'". EITB.com. 20 October 2011. Retrieved 20 October 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 "Basque group Eta says armed campaign is over". BBC News. 20 October 2011. Retrieved 20 October 2011.

- ↑ Blázquez, José Ramón (1 December 2011). "Negacionismo del conflicto vasco". DEIA. Retrieved 29 May 2013.

- ↑ Ruiz Soroa, José María. El Canon Nacionalista (PDF) (in Spanish). Retrieved 1 September 2013.

- ↑ Férnandez Díaz, Jorge (18 September 2012). "Fernández Díaz: 'No ha habido conflicto político, sino terrorismo'". La Gaceta. Retrieved 29 May 2013.

- ↑ "Basagoiti admite la existencia de un conflicto que no justifica a ETA". El Mundo. 12 January 2012. Retrieved 7 January 2014.

- ↑ Urko Aiartza and Julen Zabalo (2010). The Basque Country: The Long Walk to a Democratic Scenario Berghof Transitions Series No. 7 (PDF). Berghof Conflict Research. p. 7. ISBN 978-3-941514-01-0. Retrieved 1 September 2013.

There is no unanimous agreement when it comes to determining the reasons for the so-called Basque conflict. According to different sources, it is either a long conflict with historical roots, an instrument of Basque nationalist politics, an attempt to impose a privilege, or evidence of the state's obstinacy. Whichever of these may be the case, an understanding of the historical relations between the Basque provinces and the Spanish and French states is indispensable in order to explain the present conflict.

- ↑ "Autonomy games, tensions with the regions ahead of next March's general election in libia". economist.com. 27 September 2007. Retrieved 1 November 2010.

- ↑ http://politica.elpais.com/politica/2016/04/12/actualidad/1460482561_623398.html

- ↑ "Carrero, Franco y ETA". diariovasco.com (in Spanish). 26 December 2006. Retrieved 1 November 2010.

- ↑ "Entre la traición y la heroicidad". elpais.com (in Spanish). 5 November 2004. Retrieved 1 November 2010.

- ↑ "ETA: la dictadura del terror, KAS". elmundo.es (in Spanish). 2009. Archived from the original on 17 November 2010. Retrieved 1 November 2010.

- 1 2 3 "Siempre acosados pero más vivos que nunca". gara.net (in Spanish). 30 October 2010. Archived from the original on 1 November 2010. Retrieved 1 November 2010.

- ↑ "Las 27 víctimas de la vergüenza: la guerra sucia del GAL se prolongó durante cuatro duros años". noticiasdegipuzkoa.com (in Spanish). 18 October 2008. Archived from the original on 22 October 2008. Retrieved 1 November 2010.

- ↑ "Elecciones Parlamento Europeo Junio 1987". elecciones.mir.es (in Spanish). 1987. Retrieved 1 November 2010.

- ↑ "Felipe González y las conversaciones de Argel". elmundo.es (in Spanish). 2009. Archived from the original on 30 October 2010. Retrieved 1 November 2010.

- ↑ "Bidart: la caída de la cúpula de ETA". expansion.com (in Spanish). Retrieved 1 November 2010.

- ↑ ""Txelis", el padre de la kale borroka". elmundo.es/cronica (in Spanish). 23 September 2001. Archived from the original on 5 November 2010. Retrieved 1 November 2010.

- ↑ "La dictadura del terror: Las treguas de ETA". elmundo.es/ (in Spanish). 2009. Archived from the original on 6 November 2010. Retrieved 1 November 2010.

- ↑ "El día en que todos fuimos Miguel Ángel Blanco". elpais.com (in Spanish). 8 July 2007. Retrieved 1 November 2010.

- 1 2 "Las siglas políticas de ETA". rtve.es (in Spanish). 23 January 2009. Archived from the original on 3 December 2010. Retrieved 1 November 2010.

- ↑ "Spanish government clamps down on Basque separatist ETA". wsws.org. 13 November 2000. Retrieved 1 November 2010.

- ↑ "Historia de Aralar". aralar.net (in Spanish). Retrieved 1 November 2010.

- ↑ "Batasuna banned permanently". news.bbc.co.uk. 17 March 2003. Retrieved 1 November 2010.

- ↑ The whole sentence of Audiencia Nacional in the Egunkaria case, passed on 12 April 2010.

- ↑ "The Basque newspaper Egunkaria closed down by the Spanish government". euskalherria.info. 21 February 2003. Retrieved 1 November 2010.

- ↑ "El Supremo rebaja las condenas del 18/98 y desmonta ahora la tesis usada para cerrar «Egin»", Gara, 27 May 2009.

- ↑ The whole sentence of Tribunal Supremo in the Egin case, 22 May 2009.

- ↑ Webb, Jason (16 January 2007). "Analysis – Spain's PM down but not out after ETA bomb". reuters.com. Retrieved 1 November 2010.

- ↑ "¡Habrá guerra para 40 años o más!". El País. 5 December 2011. Retrieved 2 January 2014.

- ↑ "Who are ETA?". bbc.co.uk/news. 5 September 2010. Archived from the original on 3 November 2010. Retrieved 1 November 2010.

- ↑ "Spain bans political party for ETA links". edition.cnn.com. 16 September 2009. Retrieved 1 November 2010.

- ↑ "Detienen a Otegi y a otros nueve dirigentes en otro golpe a Batasuna en la sede del sindicato LAB". rtve.es (in Spanish). 13 October 2009. Archived from the original on 25 October 2010. Retrieved 1 November 2010.

- ↑ "Falange y Tradición quería captar adeptos y comprar armas para proseguir sus ataques". noticiasdenavarra.com (in Spanish). 9 March 2010. Retrieved 27 December 2010.

- ↑ "Cronología de las detenciones de presuntos miembros de ETA en el 2010". rtve.es (in Spanish). 21 August 2010. Archived from the original on 27 October 2010. Retrieved 1 November 2010.

- ↑ "The Abertzale Left about ETA's announce to cease armed activities". ezkerabertzalea.info. 13 September 2010. Archived from the original on 24 November 2010. Retrieved 1 November 2010.

- 1 2 Minder, Raphael (18 October 2011). "Peace Talks Pressure Basque Separatists to Disarm". The New York Times. Retrieved 19 October 2011.

- ↑ "Annan and Adams top list of experts at Donostia Peace Conference". EITB.com. 17 October 2011. Retrieved 18 October 2011.

- ↑ Europa Press (19 October 2011). "Tony Blair y Jimmy Carter suman sus apoyos a la declaración de la Conferencia". El Mundo. Retrieved 19 October 2011.

- ↑ "International negotiators urge Eta to lay down weapons". BBC News. 17 October 2011. Retrieved 19 October 2011.

- ↑ "Detenido el jefe del aparato militar de ETA, según Interior" (in Spanish).

- ↑ "La primera víctima de ETA". El País (in Spanish). Retrieved 1 November 2010.

- ↑ Serón, Luís; San José, Tais (2013-05-05). "'Begoña Urroz sigue siendo una víctima del terrorismo, pero no de ETA'". EITB. Retrieved 2016-09-28.

- ↑ Fernández Soldevilla, Gaizka (2014-06-28). "La primera víctima mortal de ETA no fue Begoña Urroz". La Tribuna del País Vasco. Retrieved 2016-09-28.

- ↑ "Balance de dolor". Colectivo de Víctimas del Terrorismo en el País Vasco (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 4 July 2010. Retrieved 1 November 2010.

- ↑ "Víctimas del Terrorismo". Asociación de Víctimas del Terrorismo (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 16 October 2010. Retrieved 1 November 2010.

- ↑ "La enigmática tragedia del monte Oiz: ¿fue o no un atentado de ETA". 20 February 2012. Retrieved 24 September 2016.

- ↑ "Detenida Jone Amezaga para su ingreso en prisión." (El Pais, 15 Decamber 2014). Retrieved 5 May 2015.

- ↑ "ETA pulveriza su récord histórico de pistoleros presos: 762". ABC. Retrieved 11 March 2015.

- ↑ "Large separatist protest calls on Spain to repatriate Basque prisoners to jails close to home". Fox News, 12 January 2013. Retrieved 11 March 2015.

- ↑ "Rajoy no revisará la dispersión de presos si ETA no se disuelve.". La Razon, 31 December 2011. Retrieved 11 March 2015.

- ↑ "Thousands protest over Basque prisoners". BBC, 28 November 1998. Retrieved 28 January 2015.

- ↑ "Thousands of Basque protesters march for ETA prisoners in defiance of Madrid". Japan times, 12 January 2014. Retrieved 28 January 2015.

- ↑ "Huge march in Spain after ban on Eta prisoner rally". BBC, 11 January 2014. Retrieved 28 January 2015.

- ↑ "Thousands protest in Bilbao over conditions for ETA prisoners". Expatica, 12 January 2013. Retrieved 11 March 2015.

- ↑ "Paramilitary prisoners are freed". BBC, 28 July 2000. Retrieved 29 January 2015.

- ↑ "La 'Vía Nanclares' explicada en diez preguntas". eldiario, 15 May 2012. Retrieved 11 March 2015.

Further reading

- ETA. Historia política de una lucha armada by Luigi Bruni, Txalaparta, 1998, ISBN 84-86597-03-X

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Basque conflict. |

- El Mundo's special page about the conflict

- Spanish Interior Ministry page about ETA

- Abertzale left official page