Banksia serrata

| Saw banksia | |

|---|---|

| | |

| Tree of Banksia serrata at Villa Durazzo-Pallavicini | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| (unranked): | Angiosperms |

| (unranked): | Eudicots |

| Order: | Proteales |

| Family: | Proteaceae |

| Genus: | Banksia |

| Subgenus: | Banksia subg. Banksia |

| Section: | Banksia sect. Banksia |

| Series: | Banksia ser. Banksia |

| Species: | B. serrata |

| Binomial name | |

| Banksia serrata [1] L.f. | |

| |

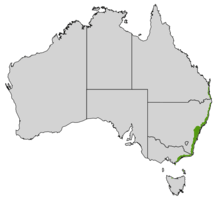

| Range of Banksia serrata in green | |

Banksia serrata, commonly known as old man banksia, saw banksia, saw-tooth banksia and red honeysuckle, is a species of woody shrub or tree of the genus Banksia in the family Proteaceae. Native to the east coast of Australia, it is found from Queensland through to Victoria with outlying populations on Tasmania and Flinders Island. Commonly growing as a gnarled tree up to 15 m (50 ft) in height, it can be much smaller in more exposed areas. This Banksia species has wrinkled grey bark and shiny dark green serrated leaves, with large, yellow or greyish-yellow flower spikes, known as inflorescences, appearing over the summer. The flower spikes turn grey as they age and large grey follicles appear.

It is one of the four original Banksia species collected by Sir Joseph Banks in 1770, and one of four species published in 1782 as part of Carolus Linnaeus the Younger's original description of the genus. There are no recognised varieties, although it is closely related to Banksia aemula. It grows exclusively in sandy soils, and is usually the dominant plant in scrubland or low woodland. Banksia serrata is pollinated by and provides food for a wide array of vertebrate and invertebrate animals in the autumn and winter months. It is an important source of food for honeyeaters. It is a common plant of parks and gardens.

Description

Banksia serrata usually grows as a gnarled and misshapen tree up to 15 m (50 ft) tall, although in some coastal habitats it grows as a shrub of 1–3 m (3–10 ft), and on exposed coastal cliffs it has even been recorded as a prostrate shrub. As a tree, it usually has a single, stout trunk with the rough grey bark characteristic of Banksia. Trunks are often black from past bushfires, and ooze a red sap when injured. The leaves are dark glossy green above and light green below, 8 to 20 centimetres (3 to 8 in) long, and 2 to 4 centimetres (0.8 to 2 in) wide. Except near the base of the leaf, the margins are serrated with lobes between 1 and 3 millimetres (0.04 and 0.1 in) deep. Leaves occur crowded together at the upper end of branches, giving the canopy a thin, sparse appearance. The flowers are a silvery grey colour, with cream or golden styles, and occur in Banksia's distinctive cylindrical flower spikes. "Cones" may have up to 30 follicles, and usually appear hairy due to the retention of old withered flower parts.[2]

Taxonomy

Banksia serrata was first collected at Botany Bay on 29 April 1770, by Sir Joseph Banks and Dr Daniel Solander, naturalists on the Endeavour during Lieutenant (later Captain) James Cook's first voyage to the Pacific Ocean.[3][4] However, the species was not published until April 1782, when Carolus Linnaeus the Younger described the first four Banksia species in his Supplementum Plantarum, commenting that it was the showiest species in the genus.[5] As the first named species of the genus, Banksia serrata is considered the type species.

Under Brown's taxonomic arrangement, B. serrata was placed in subgenus Banksia verae, the "true banksias", because the inflorescence is a typical Banksia flower spike. Banksia verae was renamed Eubanksia by Stephan Endlicher in 1847, and demoted to sectional rank by Carl Meissner in his 1856 classification. Meissner further divided Eubanksia into four series, with B. serrata placed in series Quercinae on the basis of its toothed leaves.[6] When George Bentham published his 1870 arrangement in Flora Australiensis, he discarded Meissner's series, replacing them with four sections. B. serrata was placed in Orthostylis, a somewhat heterogeneous section containing 18 species.[7] This arrangement would stand for over a century.

In 1891, German botanist Otto Kuntze challenged the generic name Banksia L.f., on the grounds that the name Banksia had previously been published in 1775 as Banksia J.R.Forst & G.Forst, referring to the genus now known as Pimelea. Kuntze proposed Sirmuellera as an alternative, republishing B. serrata as Sirmuellera serrata. The challenge failed, and Banksia L.f. was formally conserved.[8]

Current placement

Alex George published a new taxonomic arrangement of Banksia in his classic 1981 monograph The genus Banksia L.f. (Proteaceae).[8] Endlicher's Eubanksia became B. subg. Banksia, and was divided into three sections. B. serrata was placed in B. sect. Banksia, and this was further divided into nine series, with B. serrata placed in B. ser. Banksia (formerly Orthostylis).[2][lower-alpha 1]

In 1996, Kevin Thiele and Pauline Ladiges published a new arrangement for the genus, after cladistic analyses yielded a cladogram significantly different from George's arrangement. Thiele and Ladiges' arrangement retained B. serrata in series Banksia, placing it in B. subser. Banksia along with aemula as its sister taxon (united by their unusual seedling leaves) and ornata as next closest relative.[9] This arrangement stood until 1999, when George effectively reverted to his 1981 arrangement in his monograph for the Flora of Australia series.[2]

Under George's taxonomic arrangement of Banksia, B. serrata's taxonomic placement may be summarised as follows:

In 2002, a molecular study by Austin Mast again showed the three eastern species to form a group, but they were only distantly related to other members of the series Banksia. Instead, they formed a sister group to a large group comprising the series Prostratae, Ochraceae, Tetragonae (including Banksia elderiana), Banksia lullfitzii and Banksia baueri.[10]

In 2005, Mast, Eric Jones and Shawn Havery published the results of their cladistic analyses of DNA sequence data for Banksia. They inferred a phylogeny greatly different from the accepted taxonomic arrangement, including finding Banksia to be paraphyletic with respect to Dryandra.[11] A new taxonomic arrangement was not published at the time, but early in 2007 Mast and Thiele initiated a rearrangement by transferring Dryandra to Banksia, and publishing B. subg. Spathulatae for the species having spoon-shaped cotyledons; in this way they also redefined the autonym B. subg. Banksia. They foreshadowed publishing a full arrangement once DNA sampling of Dryandra was complete. In the meantime, if Mast and Thiele's nomenclatural changes are taken as an interim arrangement, then B. serrata is placed in B. subg. Banksia.[12]

Intraspecific variation

Banksia serrata is a fairly uniform species, showing little variation between different habitats other than occasionally occurring as a shrub in coastal areas. No subspecific taxa are recognised.

Distribution and habitat

Banksia serrata occurs on the Australian mainland from Wilsons Promontory (39°08′ S) in Victoria to the south, north to Maryborough, Queensland (25°31′ S). There is also a large population at Sisters Creek in Tasmania and another in the south west corner of the Wingaroo Nature Reserve in the northern part of Flinders Island. The Wingaroo NR Conservation Plan (2000) reports that the population comprises around 60 to 80 individual trees, the majority of which are believed to be quite old. It adds there is evidence of slow and continuous regeneration, which appears to be occurring in the absence of fire.

Throughout its range, Banksia serrata is found on well-drained sandy soil, and is often found on stabilised soil near the coast but just behind the main dune system.

Banksia serrata is a component of the Eastern Suburbs Banksia Scrub (ESBS), designated an endangered ecological community. This community is found on younger, windblown sands than the heathlands to the north.[13]

Ecology

This species is a food source for a number of bird species. Nectar eating birds and that have been observed feeding at the flowers include bell miner (Manorina melanophrys) and white-cheeked honeyeater (Phylidonyris nigra). The immature follicles are eaten by yellow-tailed black cockatoo (Calyptorhynchus funereus).[14] Banksia serrata is a host plant for the larval and adult stages of the buprestid beetle Cyrioides imperialis.[15]

Banksia serrata has a central taproot and few lateral roots. Clusters of fine branched proteoid roots up to 15 cm (6 in) long arise from larger roots.[16] These roots are particularly efficient at absorbing nutrients from nutrient-poor soils, such as the phosphorus-deficient native soils of Australia.[17]

Banksia serrata plants generally become fire tolerant by 5 to 7 years of age in that they are able to resprout afterwards,[18] generally from epicormic buds under their thick bark if the plant is between 2 and 6 m high or from the woody subterranean base known as the lignotuber of younger and smaller plants. Stem size is the critical factor, with stems of under 1 cm diameter dbh unable to withstand low intensity fires. A stem/trunk diameter of 2 cm dbh is needed to survive low intensity firest and around 5 cm dbh the size to withstand a high intensity fire.[19] As with other Banksia species, B. serrata trees are naturally adapted to the presence of regular bushfires and exhibit a form of serotiny known as pyriscence. In low-intensity fires, B. serrata can recover using epicormic buds. There is doubt as to whether recovery from a lignotuber is possible, although it has been demonstrated in other Banksia species such as B. menziesii.[20] Fire intervals of 10–15 years are recommended for the Eastern Suburbs Banksia Scrub, as longer leads to overgrowth by Leptospermum laevigatum,[21] while an interval of at least 9 years was indicated in a study at Brisbane Water National Park.[22] Repeated intervals of 5 year's duration or less will result in decline of population as young plants are not yet resistant to fire, and their tall habit makes them especially vulnerable.[19]

The seedbank is most productive between 25 and 35 years after a previous fire. However seedlings may be outcompeted by seedlings of obligate seeder species.[22]

Banksia serrata has shown a variable susceptibility to dieback from the pathogen Phytophthora cinnamomi, with plants in sandier soils showing more resistance than those in heavier soils. Plants from Wilsons Promontory were sensitive. The resistance of plants from Flinders Island is unknown. The small size of the stand renders it vulnerable to eradication.[23]

Cultivation

B. serrata can be grown readily from seed, collected after heating the "cone". A sterile, free-draining seed raising mixture should be used to prevent damping off.[24] In cultivation, though relatively resistant to 'dieback', it does require a well drained soil, preferably fairly sandy and a sunny aspect. Summer watering is also helpful. Note that the plant may take several years to flower. It is often used in amenities plantings in streets, parks and public gardens in areas to which it is native.

Banksia serrata is also used in bonsai.[25]

Cultivars

- Banksia 'Pygmy Possum' - originally propagated by Austraflora Nursery, this is a prostrate form originally from Green Cape area on the NSW far south coast. Similar plants are now seen in nurseries called simply B. serrata (Prostrate) collected from the same area. This plant is suitable for rockeries and small gardens.[26]

- Banksia 'Superman' - selection from large flowered (spikes to 27 centimetres (11 in) high) and large leaved population from Scotts Head on NSW mid north coast. As yet, not in commercial cultivation, though is registered with ACRA.

Notes

- ↑ George's 1981 publication of B. ser. Orthostylis was illegal, as the inclusion of B. serrata, meant that it was required under the International Code of Botanical Nomenclature to be given the autonym Banksia L.f. ser. Banksia . This has been recognised and corrected in later publications.[2]

References

- ↑ "Banksia serrata L.f.". Australian Plant Name Index (APNI), IBIS database. Centre for Plant Biodiversity Research, Australian Government.

- 1 2 3 4 George, Alex S. (1999). "Banksia". In Wilson, Annette (ed.). Flora of Australia. Volume 17B: Proteaceae 3: Hakea to Dryandra. Collingwood, Victoria: CSIRO Publishing / Australian Biological Resources Study. pp. 175–251. ISBN 0-643-06454-0.

- ↑ William J. L. Wharton, ed. (1893). Captain Cook's Journal during his First Voyage Round the World made in H. M. Bark "Endeavour" 1768–71: A Literal Transcription of the Original MSS. London: E. Stock.

- ↑ Banks, Joseph. "29 April 1770". Banks's Journal. Archived from the original on 8 October 2006. Retrieved 2006-10-25.

- ↑ Carolus Linnaeus the Younger (1782). Supplementum Plantarum. Brunsvigae: Orphanotrophei. p. 126.

- ↑ Meissner, Carl (1856). "Proteaceae". In de Candolle, A. P. Prodromus systematis naturalis regni vegetabilis, pars decima quarta (in Latin). Paris: Sumptibus Victoris Masson.

- ↑ Bentham, George (1870). "Banksia". Flora Australiensis: A Description of the Plants of the Australian Territory. Volume 5: Myoporineae to Proteaceae. London: L. Reeve & Co. pp. 541–562.

- 1 2 George, Alex S. (1981). "The Genus Banksia L.f. (Proteaceae)". Nuytsia. 3 (3): 239–473.

- ↑ Thiele, Kevin; Ladiges, Pauline Y. (1996). "A cladistic analysis of Banksia (Proteaceae)". Australian Systematic Botany. 9 (5): 661–733. doi:10.1071/SB9960661.

- ↑ Mast, Austin R.; Givnish, Thomas J. (August 2002). "Historical biogeography and the origin of stomatal distributions in Banksia and Dryandra (Proteaceae) based on their cpDNA phylogeny". American Journal of Botany. 89 (8): 1311–1323. doi:10.3732/ajb.89.8.1311. ISSN 0002-9122. PMID 21665734. Retrieved 2 July 2006.

- ↑ Mast, Austin R.; Jones, Eric H.; Havery, Shawn P. (2005). "An assessment of old and new DNA sequence evidence for the paraphyly of Banksia with respect to Dryandra (Proteaceae)". Australian Systematic Botany. CSIRO Publishing / Australian Systematic Botany Society. 18 (1): 75–88. doi:10.1071/SB04015.

- ↑ Mast, Austin R.; Thiele, Kevin (2007). "The transfer of Dryandra R.Br. to Banksia L.f. (Proteaceae)". Australian Systematic Botany. 20: 63–71. doi:10.1071/SB06016.

- ↑ "Eastern Suburbs Banksia Scrub in the Sydney Basin Bioregion" (PDF). National Parks and Wildlife Service, New South Wales Government. February 2004. Retrieved 8 August 2015.

- ↑ Barker, R.D.; Vestjens, W.J.M. (1984). The Food of Australian Birds. Melbourne University Press. pp. 1:330, 2:197, 232, 458. ISBN 0-643-05006-X.

- ↑ Hawkeswood, Trevor J. (2007). "A review of the biology and a new larval host plant for Cyrioides imperialis (Fabricius, 1801)(Coleoptera: Buprestidae)" (PDF). Calodema. Supplementary Paper No. 25: 1–3.

- ↑ Purnell , Helen M. (1957). "Studies of the family Proteaceae. I. Anatomy and morphology of the roots of some Victorian species". Australian Journal of Botany. 8 (1): 38–50. doi:10.1071/BT9600038.

- ↑ Lamont, Byron B. (1993). "Why are hairy root clusters so abundant in the most nutrient-impoverished soils of Australia". Plant and Soil. 156 (1): 269–72. doi:10.1007/BF00025034.

- ↑ Benson, Doug; McDougall, Lyn (2000). "Ecology of Sydney Plant Species Part 7b:Dicotyledon families Proteaceae to Rubiaceae" (PDF). Cunninghamia. 6 (4): 1017–1202 [1038]. Retrieved 21 July 2016.

- 1 2 Bradstock,R.A.; Myerscough, P.J. (1988). "The Survival and Population Response to Frequent Fires of Two Woody Resprouters Banksia serrata and Isopogon anemonifolius". Australian Journal of Botany. 36 (4): 415–31. doi:10.1071/BT9880415.

- ↑ Mibus, Raelene; Sedgley, Margaret (24 May 2000). "Early Lignotuber Formation in Banksia –Investigations into the Anatomy of the Cotyledonary Node of Two Banksia (Proteaceae) Species". Annals of Botany. 86: 577. doi:10.1006/anbo.2000.1219.

- ↑ Best practice guidelines: Eastern Suburbs Banksia Scrub (PDF). Sydney: Department of Environment and Climate Change NSW. January 2009. p. 9. ISBN 978-1-74232-091-5. Retrieved 8 August 2015.

- 1 2 Bradstock,R.A. (1990). "Demography of woody plants in relation to fire: Banksia serrata Lf. and Isopogon anemonifolius (Salisb.) Knight". Austral Ecology. 15 (1): 117–32. doi:10.1111/j.1442-9993.1990.tb01026.x.

- ↑ Natural and Cultural Heritage Division (2014). Flinders Island Natural Values Survey 2012 (PDF). Hobart: Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water and Environment. p. 24. ISBN 978-0-9922694-3-2.

- ↑ "Growing Banksias from seed". http://www.anbg.gov.au. Retrieved 11 January 2015. External link in

|website=(help) - ↑ "Australian Native Plants as Bonsai". Australian National Botanic Gardens. Retrieved 2006-11-14.

- ↑ Stewart, Angus (2001). Gardening on the Wild Side. Sydney: ABC Books. p. 102. ISBN 0-7333-0791-4.

| Wikispecies has information related to: Banksia serrata |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Banksia serrata. |

| Latin Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

External links

- "Banksia serrata L.f.". Flora of Australia Online. Department of the Environment and Heritage, Australian Government.

- Boland, D. J. (1984). Forest Trees of Australia (Fourth edition revised and enlarged). Collingwood, Victoria, Australia: CSIRO Publishing. ISBN 0-643-05423-5.

- George, Alex S. (1981). "The Genus Banksia L.f. (Proteaceae)". Nuytsia. 3 (3): 239–473.

- Taylor, Anne; Hopper, Stephen (1988). The Banksia Atlas (Australian Flora and Fauna Series Number 8). Canberra: Australian Government Publishing Service. ISBN 0-644-07124-9.

- Liber, C (2004). "Update on Eastern Cultivars". Banksia Study Group Newsletter. [ASGAP]. 5 (1): 3–5. ISSN 1444-285X.