Banjo roll

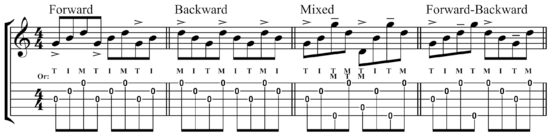

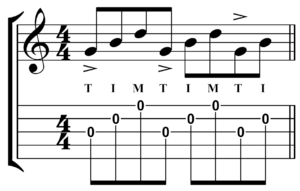

In bluegrass music, a banjo roll or roll is an accompaniment pattern played by the banjo that uses a repeating eighth-note arpeggio – a broken chord – that by subdividing the beat 'keeps time'. "Each ["standard"] roll pattern is a right hand fingering pattern, consisting of eight (eighth) notes, which can be played while holding any chord position with the left hand."[1]

"When used as back-up, the same pattern can be repeated over and over throughout an entire song, (...[with chord changes] as required), or the roll patterns can be combined with one another and with [back-up licks]... The roll patterns can also be used to embellish the vamping style of back-up, especially when the chords are played high... These roll patterns can be used as back-up for any song played at any tempo."[1] The banjo is commonly played in open tunings, such as open G (as are all of the examples): G'DGBD', allowing rolls to be practiced on all open strings (without fretting). Rolls are a distinguishing characteristic of Scruggs style banjo playing, with older styles being more melodic.[5] The older style of banjo playing has been described as "in 'phrases,'" and with, "really no connective tissue between four notes and next four notes...sorta like a gallop. Snuffy [Jenkins] was a little like that...old sounding, choppy...".[6]

Banjo rolls serve a variety of functions within an ensemble:

The bluegrass banjo roll...is a subdivided rhythm that by dissolving the metronomic footing of the music completes the uncoupling of rhythm and meter. Monroe's string band...was already congested with accents and with the rhythms those accents redundantly enforced; with its unbroken and continuous stream of notes sharply voiced in bright, acid tones, the banjo roll broke up this congestion, bringing about a kind of rhythmic division of labor in which several strata of rhythm were distributed among the instruments.... This is not to say that the banjo player does not call upon rhythmic accents; if he [sic] did not his music would seem little more than the mechanical ratta-tat-tat of a machine gun. But he always does so in a matrix which is consistently and thoroughly subdivided, from which the idea of the subdivided rhythm is never absent, and which has, by virtue of its African-inspired amalgamation to melodic movement, an unusual power to impart the idea to other musicians. Like the bones of the minstrel band, whose precision... 'lent articulation to the ensemble,' the banjo's flowing, sinuous, twisting ribbon of notes fills the entire length and breadth of the music, outlining its rhythmic infrastructure, sharpening and brightening its image, running within the music like a stream of water, now in a broad torrent, now in intricate rivulets below ground.— [5]

...the activity of the roll patterns creates a counter-melody which enhances the effectiveness of the melody.— [7]

Banjo rolls, the basis of the Scruggs style "pioneered by Earl Scruggs",[5] "were undoubtedly based on" classic or fingerpicking banjo, itself based upon and simultaneous with (mid-1860s) parlor-style guitar.[8]

"The word roll has different meanings for different kinds of musicians. To guitar players, a roll is a broken chord; to bluegrass-banjo players..."[9]

Rolls may start at any point in the pattern or, in other words, on any finger.[10]

See also

Sources

- 1 2 3 4 Davis, Janet (2002). [Mel Bay's] Back-Up Banjo, p.54. ISBN 0-7866-6525-4. Emphasis original.

- ↑ Collins, Eddie (2007). Introduction to Bluegrass Banjo, p.21. ISBN 0-7866-7290-0.

- 1 2 Hohwald, Geoff (1988). Banjo Primer, p.14. ISBN 1-893907-32-5. Shown without rhythm.

- ↑ Trischka, Tony (2005). Banjo for Beginners, p.14. ISBN 0-7390-3733-1.

- 1 2 3 Cantwell, Robert (2002). Bluegrass Breakdown: The Making of the Old Southern Sound, p.100. ISBN 0-252-07117-4.

- ↑ Tom Warlick, Lucy Warlick, and Robert Inman (2007). The WBT Briarhoppers, p.150. ISBN 0-7864-3144-X.

- ↑ Davis (2002), p.56. ISBN 0-7866-6525-4.

- ↑ Trischka, Tony (1992). Banjo Songbook, p.20. ISBN 0-8256-0197-5.

- ↑ Perlman, Ken (1989). Clawhammer Style Banjo, p.163. ISBN 0-931759-33-1.

- ↑ Davis (2002), p.56