Baltimore railroad strike of 1877

| Baltimore railroad strike of 1877 | |

|---|---|

| Part of Great Railroad Strike of 1877 | |

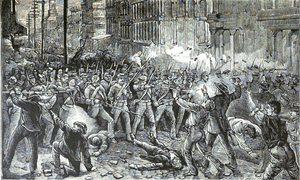

Sixth Maryland Regiment firing on the rioters in Baltimore - 1877 | |

| Date | July 16–29, 1877 |

| Location |

Baltimore, Maryland 39°17′00″N 76°37′10″W / 39.28346°N 76.619554°WCoordinates: 39°17′00″N 76°37′10″W / 39.28346°N 76.619554°W |

| Result | Some concessions later that year |

| Casualties | |

| Death(s) | 10-22[lower-alpha 1] |

The Baltimore railroad strike occurred in Baltimore, Maryland as part of the Great Railroad Strike of 1877. Strikes broke out along the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad (B&O) on July 16, the day ten percent wage reductions were to go into effect. Strikes of railroad workers and various manufacturers in Baltimore continued mostly peacefully until July 20, when Maryland Governor John Lee Carroll ordered the men of the 5th and 6th Regiments Maryland National Guard to muster and travel from Camden Station in Baltimore to Cumberland, Maryland. The regiments clashed with large crowds both at the station itself and while en route, and the 6th was forced to open fire multiple times. That night and the next day multiple fires were set throughout the city with varying degrees of success and damage caused.

It was decided that the situation in Baltimore was too dangerous to send troops away, and over the following days, large increases were made in the number of militia and police, and hundreds of federal troops were ordered to the city by President Rutherford B. Hayes. Peace was restored on July 22.

Negotiations between strikers and the B&O were unsuccessful and most strikers chose to separate from the company rather than return to work at their previous wages. The company had little problem in securing sufficient workers to reopen the lines, which it did under the guard of military and police on July 29. The company promised minor concessions at the time, and eventually enacted some reforms later that year.

Background

The Long Depression, sparked in the US by the Panic of 1873, had far reaching implications for US industry, shuttering more than a hundred railroads in the first year and cutting construction of new rail lines from 7,500 miles of track in 1872 to 1,600 miles in 1875.[9] Approximately 18,000 businesses failed between 1873 and 1875, production in iron and steel dropped as much as 45%, and a million or more lost their jobs.[10][11] In 1876, 76 railroad companies went bankrupt or entered receivership.[12]:31

In early July the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad (B&O) announced it would reduce the wages of all its workers by ten percent. One hundred miles would constitute a day's work, and crews would not receive allowances for time spent on delays at stations.[5]:27 Various meetings of the working men followed, and a committee was formed to meet with the officers of the railroad. They appealed to the Vice President, Mr. King, but he declined to meet with them.[5]:28

Most accepted the reduction, but the Firemen and those who ran the freight trains resolved to stop work in protest.[13]:17–8 However, the number of unemployed along the line was so great, owing the ongoing depression, that the company had no difficulty in replacing the striking workers. In response, the strikers resolved to occupy portions of the rail line, and to stop trains from passing unless the company would rescind the wage cuts.[13]:18

July 16

On July 16, the day the reduction would go into effect, about forty men gathered at Camden Junction, three miles from Baltimore, and stopped traffic.[13]:19 A meeting was held of rail workers who were sympathetic to the strike, but now included brakemen and engineers as well as firemen.[14]

That same day in Baltimore, hundreds of manufacturing workers struck.[1]:138[5]:30 The Baltimore Boxmakers' and Sawyers' Union sought a uniform scale of prices across employers. In total, 140 of the union's 180 members walked out.[15] Tin Can makers in the city had been on strike for higher wages for a week a this point, and their number now amounted to 800 strikers, while not more than 100 can makers in the city remained at work.[15]

July 17

At around 2:00 AM on July 17 Baltimore saw the first act of violence to emerge from the strike. A westbound train was thrown from the tracks at a switch in a suburb south of the city, which had been opened and locked by an unknown person.[14] The engine caught fire and both the engineer and the fireman were severely wounded.[5]:32 The strikers denied any involvement.[14]

That afternoon violence broke out in Martinsburg, West Virginia between workers and militia guarding a train, and continued such that the governor of West Virginia appealed to the President for help.[5]:32–41[lower-alpha 3] Strikers took stations at Cumberland, Maryland; Grafton, West Virginia; Keyser, West Virginia and elsewhere, and stopped freight.[5]:42 Along the line between 400 and 500 men had joined the rail strike, and in Martinsburg alone 75 trains were halted, accounting for 1,200 rail cars.[14]

In Baltimore police were dispatched at Camden Junction, Mount Clare and Riverside station. Governor Carrol arrived in at 3:00 PM, and met with Vice President King of the B&O, along with General James Herbert, and a police commissioner.[14] That day, The Sun reported the situation in the city:

One by one the shops have become wholly or partly silent, and very many men, especially in South Baltimore, are without work or the means of providing for their families. This state of affairs is confined not along to railroad shops, but to other workshops, and a great deal of distress exists among the workingmen of all kinds.[15]

July 18

On July 18, the railroad strikers in Baltimore printed and circulated a list of their grievances:

They had submitted to three reductions of wages in three years; that they would have acquiesced in a moderate reduction; that they were frequently sent out on a trip to Martinsburg, and there detained four days at the discretion of the company, for which detention they were allowed pay but two day's time; that they were compelled to pay their board during the time they were detained, which was more than the wages they received; that they had nothing left with which to support their families; that it was a question of bread with them; that when times were dull on the road they could not get more than fifteen day's work in a month; that many sober, steady economical men became involved in debt last winter; that honest men had their wages attached because they could not meet their expenses; that by a rule of the company any man who had his wages attached should be discharged; that this was a tyranny to which no rational being should submit, and that it was utterly impossible for a man with a family to support himself and family at the reduced rate of wages.[5]:43[lower-alpha 4]

Instructions were given to the regimental commanders of the Maryland National Guard to keep their men at the ready. Captain Zollinger summoned the first sergeants of the 5th Regiment, and gave instructions for mustering the men in the event of a crisis. Colonel Peters and Adjutant Bishop made similar preparations with the 6th Regiment.[16] General Barry, commander at Fort McHenry in Baltimore, received marching orders for 75 men to move to Martinsburg to address ongoing disturbances there. They departed by rail, and were joined by eight companies of federal troops from Washington, DC.[16]

July 19

By the end of July 19, the strike had spread to span major cities from Baltimore to Chicago. It involved multiple rail companies,[lower-alpha 5] and had grown to include a variety of mechanics, artisans and laborers. General violence threatened to break out in Pittsburgh and the city was blockaded.[5]:53–5[17][lower-alpha 6]

Numerous meetings and conferences of the working discontent continued to take place across the country.[5]:53–5 A committee representing the strikers among engineers, conductors, firemen, and brakemen departed Baltimore to ensure solidarity along the line in demanding $2 per hour. The city was peaceful, but anxious, as many awaited word of the happenings in Martinsburg, which was seen as the central point of the movement.[17]

July 20

By Friday July 20, around 250 trains sat idle in Baltimore as a result of the strike.[7] President John W. Garrett of the B&O requested that Maryland Governor John Lee Carroll move state troops from Baltimore to Cumberland, where the situation had deteriorated.[5]:62–3 At 4:00 PM Brigadier General James R Herbert was ordered by Governor Carroll to muster the troops of the 5th and 6th Regiments, Maryland National Guard, to their respective armories in preparation.[1]:138[18] With knowledge that groups of workers had been dispersed along the lines to impede traffic, including the movement of troops, he issued a simultaneous declaration to the people of the state:

I ... by virtue of the authority vested in me, do hereby issue this my proclamation, calling upon all citizens of this State to abstain from acts of lawlessness, and aid lawful authorities in the maintenance of peace and order.[13]:52

Crowds had gathered at four different points in the city and along the route it was believed the soldiers would take in order to embark on their trains. Mayor Ferdinand Latrobe issued a proclamation, reciting the riot act and ordering the crowds to disperse, but to no effect.[5]:68 He later sent correspondence to the governor, asking that the garrison not be taken from the city given the current state of affairs.[lower-alpha 7] Police commissioners ordered the closing of all bar rooms and saloons.[3]:90

At 6:35 PM, as many workers in the city were ending their shifts, the alarm was sounded to gather the troops of the 5th and 6th Regiments.[13]:53[18] This was the first time such an alarm had been used in the city and it caused a great deal of excitement, and attracted yet more into the streets to witness events.[5]:70[lower-alpha 8]

The 5th Regiment

Between 135 and 250 men[lower-alpha 9] of the 5th Regiment, Maryland National Guard mustered at their armory on the corner of Fifth and Front streets. Each man was equipped with full uniform, Springfield breech loading rifle, and twenty rounds of ammunition.[13]:53 At 7:00 PM the group began their march toward Camden Station, with the intention to there board a train to Cumberland.[5]:65[13]:53

Onlookers had gathered to watch the procession,[13]:52–4[lower-alpha 10] and the soldiers were attacked on Eutaw Street by crowds throwing bricks and stones.[lower-alpha 11] No serious damage was done, and they continued until again, on Eutaw near Camden Street, they were stopped by the crowd, who injured several with their missiles.[13]:55

The order was given and the group formed up across the entire street, from curb to curb. They fixed bayonets and advanced toward their objective. Shots were fired at the body of troops, but all successfully moved through the crowd and to the station.[1]:138[3]:92[6]

The 6th Regiment

Around 6:30 PM the soldiers of the 6th Regiment began assembling.[3]:98[7]:735 Their armory was located on Front Street, across form the Phoenix Shot Tower, and consisted of the second and third floors of a warehouse, with the only exit being a narrow stairway through which no more than two men could walk abreast.[3]:98[lower-alpha 12]

The men were met with jeers by a crowd of 2,000 to 4,000 who had gathered there.[5]:70–1[7]:734 This escalated into paving stones thrown through the door and windows of the building. Soldiers who subsequently arrived were beaten or driven away.[13]:57[lower-alpha 13] Additional police were sent for, in hopes of clearing the way and relieving the troops of the need to use force against the crowd, but those who arrived were unable to affect any order, and were forced to shelter in the armory along with the soldiers.[13]:57[18]

Shortly after 8:00 PM, Colonel Peters ordered three companies of 120 men of the 6th to move as commanded by the governor and General Herbert to Camden station.[5]:71[13]:58[lower-alpha 14][lower-alpha 15] As they exited, they were assaulted by stones from the crowd, believing those of the 6th Regiment had only blank cartridges. The troops returned fire, with live ammunition as they were equipped, and the frightened crowd retreated west across the Fayette street bridge.[3]:99[lower-alpha 16] Given a temporary reprieve, the troops marched south, by way of Front Street, and then West along Baltimore Street.

The crowd regained their resolve, and as the body marched near Harrison Street[lower-alpha 17] and Frederick Street, they were attacked in the rear and made to halt by the pressing of the crowd.[3]:99[13]:58 Without orders, some of the soldiers fired on the crowd, killing one and wounding one to three.[3]:99[13]:58–9 The crowd shrank back and the soldiers were allowed continue until they had advanced to the offices of the newspaper, the Baltimore American, near Holliday Street, where an order was given to halt and two volleys fired into the crowd.[5]:71–2 Still a third time they were forced to halt as they turned onto Charles Street, and again fire on the crowd near Light Street.[5]:72 There two men and one boy were killed.[3]:99 From there they followed Charles to Camden Street and on to the station.[lower-alpha 18]

Attack on the depot

At about 8:30 PM, the men of the 5th and 6th regiments met at the Camden station along with some 200 police.[13]:59–60[18] Governor Carroll and Mayor Latrobe were present at the station, along with B&O Vice President King, General Herbert and his staff, and a number of police commissioners.[18] It was definitively decided that conditions were too dangerous to send any troops away to Cumberland.[13]:59–60

The train intended for the transportation of the troops, consisted of 11 cars, and the engine was steamed and ready for departure. The crowd fell on the engine, assailing it with stones, disabling it, and driving off both its engineer and fireman.[3]:93 At 9:15 PM another train was sent down the tracks with no one on board, to wreck itself into yet another.[13]:55[18] The tracks were torn up from Lee Street, along Ohio Avenue to Cross Street, as well as elsewhere in the suburbs.[18]

By 10:00 PM the mob that had gathered at the station, and which filled the streets for several blocks, numbered as many as 15,000.[7]:736

The soldiers and police worked to keep the mob at bay, and drove them to the far end of the station near Lee Street.[lower-alpha 19] There they assailed the buildings of the depot with stones.[13]:60 At 10:30 PM the rioters set fire to passenger cars, the dispatcher's office, and the round house.[13]:60 Some of the firefighters dispatched to the scene were driven off, and others had their hoses cut when they attempted to set up their pumps, but under the protection of the police and soldiers the flames were extinguished.[7]:737 The fires damaged one passenger car and engine, destroyed the dispatcher's office, and damaged the roof of the depot's shed.[18] Two subsequent fires were started in the south of the city, but were dealt with without major damage.[5]:74

That night Governor Carroll requested federal assistance from the President Rutherford B. Hayes, convinced by the day's events that the state forces were insufficient. General William Barry, commander at Fort McHenry, was ordered to hold all available forces in the ready.[4]:192–3[13]:63–4

The men of the 5th and 6th stayed at the depot throughout the night and into the next morning. If any individual had to leave, they did so in civilian clothes and unarmed for fear of the crowd should they be discovered to be a member of the militia.[5]:75 Camden Street remained under constant guard by 16 sentinels. They served in two hour shifts, with four hours rest in between.[3]:96

Casualties

Sources differ on the total casualties that day. By Stover's account, only 59 men of the 6th reached their destination, and the group suffered 10 killed, more than 20 seriously wounded, and several dozen more with minor injuries.[1]:139 By Stowell's account, only one militiaman was killed, but as many as half of their number deserted along the march.[2]:4 In their struggle to enter Camden Station, the 5th suffered 16 to 24 casualties, but none seriously wounded or killed.[1]:138[3]:92[6] Between 9 and 12 of the rioters were killed, and 13-40 injured.[2]:4[3]:99[4]:192[lower-alpha 20]

July 21

Through early hours of that Saturday, many from the 6th Regiment deserted, until only 11 were left, who were then incorporated into the ranks of the 5th.[3]:96

That morning, all business remained suspended.[3]:96 The bars in Baltimore remained closed, and a guard of soldiers and police protected workers as they set about the task of repairing the tracks and restoring the station to operating order. Toward nightfall, a battery of artillery was stationed at the depot.[13]:65

President Hayes released a proclamation in which he admonished:

all good citizens ... against aiding, countenancing, abetting or taking part in such unlawful proceedings, and I do hereby warn all persons engaged in or connected with said domestic violence and obstruction of the laws to disperse and retire peaceably to their respective abodes on or before twelve o'clock noon of the 22d day of July[13]:64–5

After dark, a mob of 2,500 to 3,000 gathered at Camden Station, jeering the soldiers. The crowd grew increasingly restless until stones and pistols once again assaulted the soldiers guarding the area around the depot.[3]:101–2 The sentinels were called in, the soldiers assembled, and the command given to "Load, ready, aim!" at the mob. The crowd, familiar with what was to follow, dispersed and the regiment was not ordered to fire.[3]:102 On Eutaw Street, where the sentinels had remained, the men fixed bayonets, and briefly struggled with the crowd as they attempted and failed to break the line.[3]:102

There was an exchange of gunfire between the crowd and police,[6] and between 9:00 and 10:00 PM the guards enacted a strategy, whereby the police officers, backed by the bayonets of the soldiers, advanced to the crowd and arrested each a man, who was then taken into the station, disarmed, and held there. The strategy was largely successful, and by 11:00 PM the area around the station was largely cleared, though sporadic gunfire was heard throughout the night.[13]:67 Between 165 and 200 were detained in total.[6][7]:739 The most violent of the captives were removed and taken to the police station. Four, including one police officer were injured in the exchange of fire, and several who resisted arrest were beaten severely.[6]

At the foundry near the Carey Street Bridge[lower-alpha 21] a crowd of over 100 gathered and threatened to set fire to the area. A contingent of the 5th under Captain Lipscomb arrived, and a volley fired over the heads of the crowd was sufficient to resolve the situation.[3]:103 An unsuccessful attempt was made to burn a B&O transportation barge at Fell's Point,[7]:739 and 16 were arrested in a confrontation between citizens and the police at Lee and Eutaw.[6]

That night, three separate attempts were made to set fire the 6th Regiment armory, with its first floor, full of dry fabrics and other furniture making material, vulnerable to such attack. All were frustrated by the remaining garrison of soldiers and police.[21]

Just before midnight, 120-135 marines arrived at the station and reported to the governor, who ordered them to set about capturing the leaders of the mob.[7]:739[12]:36 That evening, Governor Carroll telegraphed President Hayes that order had been restored in the city.[4]:193

July 22

Between 2:00 AM and 3:00 AM on Sunday morning, the peace was again broken and fire alarms began to ring throughout the city. To the west, at the Mount Clare Shops of the B&O, a 37 car train of coal and oil had been set fire to. Police, firefighters, and thousands of citizens flocked to the scene.[13]:68 A contingent of 50 marines was dispatched to the area to provide assistance.[3]:103 The cars which had not yet caught fire were detached from those burning, and by the time the flames were extinguished between seven and nine cars had been burned.[6][13]:68 Between $11,000 and $12,000 in damage was sustained.[3]:103[8]

At 4:00 AM another alarm sounded. The planing mills and lumber yard of J. Turner & Cate, nearby the Philadelphia Wilmington & Baltimore rail depot, had been set afire. The entire property, extending over a full city block, was destroyed. Realizing this, the firefighters set about trying to save the surrounding structures.[13]:68–9

At 9:00 AM, the first passenger trains left the city, and continued running throughout the day.[8] Around 10:00 AM, General Hancock arrived and was followed by 360-400 federal troops from New York and Fort Monroe, who relieved the those guarding the Camden station.[4]:193[13]:70 They brought with them two 12 pounder artillery pieces. From that point on, the men of the 5th and the federal troops took equal shares guarding the station.[3]:104

Around noon, General Abbot arrived at President Street, with a battalion of 99 to 114 engineers.[lower-alpha 22] As the group advanced toward the armory of the 6th regiment, where they were to be quartered, they were met by a crowd of 500.[3]:105[12]:36 Jeers from the crowd turned to missiles until one soldier, Private Corcoran, was struck in the head and wounded. Abbott gave orders that his men were to halt and fix bayonets, to which the crowd scattered.[12]:36 Upon arriving at and inspecting the armory, Abbot called it the "perfect man-trap" and "the most unsafe place" he had seen for the quartering of soldiers.[21]

Throughout the day and the previous, as many as 500 new special police were sworn in, doubling the size of the police force.[3]:104[13]:69 Each were provided a star, revolver and espantoon.[6] The recently arrived regulars brought the garrison of federal troops in the city to between 700 and 800, in addition to the police, newly appointed special police, and national guard.[13]:70–1 The vessels Powhatan and Swatara had also been ordered to the city, along with their 500 marines.[3]:104

Court was held all that day in the southern district, and 195 charges of riot and 17 charges of drunkenness were disposed.[8]

That night the city was quiet.[13]:71 A telegram was dispatched from Adjutant General Edward D. Townsend to General Hancock, having just arrived in the city earlier that day. He was directed that he and his men were to move to Pittsburgh, where riots were ongoing.[4]:320

The 7th and 8th regiments

Abbott's engineer corps re-purposed the armory of the 5th Regiment for use as a recruiting station, toward the goal of forming two new 8th Regiment, to include a company of artillery.[22] They brought with them from the armory of the 6th two howitzers, 2,000 rounds of ammunition, and 250 muskets.[3]:106 General James Howard took possession of the Academy of Music, for the purpose of forming the 7th.[22] Those who enlisted were equipped and dispatched to aid in the guarding of Camden Station.

The Governor and Adjutant General put out a call for volunteers to fill each regiment with 1,000 men. General Howard was chosen to command the 7th, and General Charles E Phelps the 8th.[3]:106

The following day at 3:00, those who were left of the original 6th Regiment would disband. No official order was given to this effect, but their duties at that point had been entirely assumed by the federal troops in the city, and the new soldiers of the city's other regiments.[22] The armory of the 6th remained guarded by a single police officer.

Conclusion

Stoppage and shortage

Although widespread violence had ceased, a pronounced military presence in the city remained and the strikes continued. With freight transport via rail still stopped, commerce in the city was forced to rely on supplies carried by water or those driven by cart. Dozens of ships remained idle in the harbor for lack of goods to transport, and those who would load and unload the ships remained out of work.[23][lower-alpha 23] The stoppage of coal threatened manufacturing throughout, including that of gas, on which the city depended for lighting.[21] On July 26, The Sun reported 3,000 draymen, 600 oil men, and 1,500 stevedores out of work as a result of the embargo.[21]

The stoppage of freight threatened the city's food supply, as inbound shipments either remained idle or were diverted to other markets that remained accessible by rail.[21] Conversely, local farmers suffered losses as their goods could not be transported out of Baltimore to be sold. This resulted in a surplus of local produce that drove down prices, in some cases, to less than half of what the same product sold for the previous year.[24]

Negotiations

On July 26 a committee from the engineers, firemen, brakemen, and conductors met with Governor Carroll. They presented him with a list of their unanimously adopted demands. The governor informed them that he had no power to satisfy them, which was a matter for the B&O, but he assured them that he intended to enforce the law and put down violence by any means necessary. The committee in turn assured Carroll that they had no connection with the violence, but merely intended to stop work until their demands were met. Carroll replied:

You have more to do than simply abstain from riotous proceedings. You must not stand behind riots and let violators of the law promote the destruction of property. You are responsible for the violence that has been done, whether you were actually engaged in it or not. You on your part must drive away from you the evil-disposed people who have done so much harm, and discountenance in the plainest way everything tending to violence.[24]

The governor also added that, should the men interfere with others who were attempting to work themselves, they would be equally in violation of the law.[24]

The next day, some railways throughout the country resumed traffic, though the B&O remained idle.[25] B&O Vice President King published a reply to the demands of the strikers, saying that they simply could not be met for lack of work and low prices for hauling freight. He wrote that the choice of the company was to either lay off workers and retain only those for whom they had work, or to spread what work was to be done among its employees, and they chose the latter as the more humane.[25] He continued:

The experience of the last ten days must satisfy everyone that if freight trains are stopped on the baltimore and Ohio Railriad, the city of Baltimore is not only deprived of the great commercial advantages with she has heretofore enjoyed, but the entire commuity is made to feel that all business must be seriously crippled and the price of all kinds of family supplies greatly increased.[25]

A committee met with King. Later, Second Vice President Keyser, upon the request of the strikers, addressed a workingmen's meeting and presented the company's written response. He said that the ten percent cut was "forced upon the company," but that he was confident they would be able to provide more full employment, thus increasing wages, due to an abundance of freight to be moved, and that a system of passes would be arranged to address the issue of idle time caused by delays in train movement. He entreated the men that if the situation could not be resolved, it must "bring want and suffering upon all; suffering from which you and your families cannot hope to be exempt."[25] He asserted that, although 90 percent of rail workers had accepted the reduction, the whole business of the railroad and city had been halted due to the 10 percent rejecting them, and resolving to not allow the rest of the men to continue work. He said the rescinding of the wage cuts were "entirely out of the question" and requested the men either return to work, or allow those who would to resume working.[25] As The Sun reported: "A vote was taken, and the proposition of the company was rejected unanimously. Mr. Keyser then withdrew from the meeting."[25]

Freight resumes

The force gathered at Camden Station at 8:30 AM on July 29 included 250 federal troops, 250 men of the 5th Maryland Regiment, and 260 policemen. Under this guard freight once again resumed traffic in and out of Baltimore.[3]:108–9[26] Strikers were present, but peaceful, and some returned to work.[26] That day 34 trains moved between the city and Cumberland over the B&O, despite certain difficulties that still existed in places on the line.[26] As business resumed, the glut of stalled products poured through the city, including four million gallons of petroleum, 1.25 million bushels of wheat, 250,000 gallons of coal oil, 1,463 head of cattle, and 90 car loads of coal.[26]

Those strikers who still held out, declared that they would not interfere, but asserted that the company would be unable to find sufficient workers without them, and by remaining united, they could yet see their terms met.[26] They were given notice to report to work on Monday July 30 or be discharged from the company. Most chose discharge, and the company had little trouble in acquiring the workers needed to run the trains.[27][28]

Aftermath

.jpg)

By the time peace was completely restored in the city, the cost to the state was between $80,000 and $85,000.[3]:107[29]

Later that year, the B&O agreed to a number of reforms including agreeing to not have crewmen called to work more than an hour before a trains departure, paying a crew a fourth of a day's pay if the train they were working was cancelled, and passes were to be given for men working who had long layovers.[1]:139–40 In 1880, the B&O Employees Relief Association was established.

The first parade of the 5th through the city following the crisis was on October 15. The regiment marched that day with 400 counted among their ranks.[3]:110 In 1901, a new armory, for the 5th was completed on West Hoffman street, and is now included on the National Register of Historical Places.[30]

In 2013 a historical marker was placed on the Howard Street side of Camden Station. It was state funded and coordinated by the Maryland Historical Trust and the Maryland State Highway Administration.[31] The text of the marker was proposed by Bill Barry, Director of Labor Studies at the Baltimore County Community College.[32]

See also

Notes

- ↑ Between 1 and 10 men of the 6th Regiment killed on July 20,[1]:139[2]:4 between 9 and twelve civilians killed on July 20[2]:4[3]:99[4]:192</ref>Injuries 51-86+[lower-alpha 2]Arrested 165-212<ref group='lower-alpha'>Between 165 and 200 arrested at Camden Station on July 21,[6][7] :739 16 arrested on July 21 at confrontation at Lee and Eutaw streets, which may or may not be counted in the above,[6] and a total of 212 charges of riot and drunkenness disposed of by the southern district court on July 22[8]

- ↑ Two severely wounded on July 17;[5]:32 more than 20 seriously wounded, and several dozen minor injuries suffered by the 6th Regiment on July 20;[1]:139[2]:4 between 16 and 24 casualties suffered by the 5th Regiment on July 20;[1]:138[3]:92[6] between 13 and 40 civilian injuries on July 20;[2]:4[3]:99[4]:192 unknown number beaten by police during arrests on July 21[6]

- ↑ On July 18, 1877 The Sun reported the events as follows: "As the train reached the switch one of the strikers, William Vandergriff, seized the switch-ball to run the train on the side track. John Poisal, a member of the militia ... jumped from the pilot of the engine and attempted to replace the switch so that the train could go on. Vandergriff fired two shots at Poisal, one causing a slight flesh wound in the side of the head. Poisal returned fire, shooting Vandergriff through the hip. Several other shots were fired at Vandergriff, striking him in the hand and arm. ... The volunteering engineer and firemen of the train ran off as soon as the shooting began." Vandergriff's arm would be amputated later that day.[14]

- ↑ For "wages attached" see Garnishment

- ↑ Striking lines included the Connellsville Branch, the Pittsburgh, Fort Wayne and Chicago Railway, the Erie Railroad, and the Pennsylvania Railroad System.[5]:57

- ↑ See Pittsburgh railway riots

- ↑ The correspondence from Mayor Ferdinand C. Latrobe, sent July 20, 1877 read as follows: "His Excellency John Lee Carroll, Governor of Maryland. Dear Sir: In view of the condition of affairs now existing in this city, and the violent demonstration that has taken place within the last hour, I would suggest that neither of the regiments of State militia be ordered to leave Baltimore this evening. I make this suggestion after a consultation with the Commissioners of Police."[5]:69

- ↑ Sounding the alarm to gather the troops was originally proposed by General Herbert, but was overridden by Governor Carroll because it was feared that the alarm would rouse public interest and cause "exaggerated alarm" among the people. When petitioned a second time by Herbert, Carroll acquiesced.[18]

- ↑ McCabe and Martin put the strength of the 5th squarely at 200,[13]:53 and Scharf puts the number at 250,[7]:734 but these may be overestimates. According to Meekin, prior to the events of July 20, the strength of the regiment had been reduced to 175, and some of these were away when the call was given to muster, so that when Captain Zollinger took command of the force, only 135 were present.[3]:91

- ↑ Laurie puts the size of the crowds at 15,000, although he does not differentiate between those encountered by the two units.[12]:35

- ↑ McCabe and Martin recorded a confrontation at the corner of Eutaw and Lombard,[13]:53–4 while Meekins recorded a confrontation at Eutaw and Franklin.[3]:92 It is not clear whether these were two separate occurrences or confused details of the same. Both sources recorded a confrontation on Eutaw near Camden.

- ↑ The first floor of the building was utilized as a furniture factory.[18]

- ↑ An unnamed soldier was thrown off a bridge but survived. MAJ A. J. George, LT Welly, and C. L. Brown were all beaten, some badly.[13]:57

- ↑ McCabe and Martin assert that 150 men were left behind to guard the armory,[13]:58 however, this conflicts with the report of Meekins, who put the total force of the regiment at 150.[3]:98 The following day The Sun reported that 150 men had been ordered to move on Camden Station, with Colonel Peters remain as ordered at the armory with a residual force of 100. However, once the companies were actually organized, 220 men were present, and three companies totaling 120 were dispatched for the depot.[18]

- ↑ General Herbert his staff themselves relocated to Camden Station at 7:30 PM. The staff who accompanied him were acting adjutant general, Major Fred Duvall; judge advocate, Major T. Wallis Blackistone; quartermaster, Captain J. W. S. Brady; aids, Captain J. Mason Jamison and Captain G. W. Wood; and ordinance officer Thomas Hillen.[18]

- ↑ As of 2016, the approximate location of the intersection of North President Street and East Fayette Street, then the location of Fayette Street as it crossed Jones Falls.[19] Also compare this map of Baltimore from 1874.

- ↑ At the time, Harrison street intersected Baltimore Street between Jones Falls and Frederick Street. Compare this map of Baltimore from 1874.

- ↑ At the time, Camden Street continued east from the station until it reached the waterfront, through the area occupied by the Baltimore Convention Center as of 2016. Compare this map of Baltimore from 1874.

- ↑ At the time, Lee Street intersected Howard street at the train yards, passing through, as of 2016, the area occupied by the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond Baltimore Branch. As of 2016, this was in the approximate area occupied by I-395, south of the intersection of Conway and Howard. Compare this map of Baltimore from 1874.

- ↑ Dacus records the names of those killed by the 6th Regiment as Thomas V. Byrne, Patrick Gill, Louis Sinovitch, Nicholas Rheinhardt, Cornelius Murphy, William Hourand, John Henry Frank, George McDowell, Otto Manck, and Mark C. Doud. James Roke and George Kemp were wounded and later died of their injuries.[5]:74

- ↑ The brass foundry, iron foundry and blacksmith shop were, at the time, in the location occupied as of 2014 by the shopping center, Mt. Clare Junction, at the corner of West Pratt Street and Carey Street.[20]

- ↑ Meekins puts the number at seven officers and 107 men.[3]:105 The Sun, reporting on June 26 puts the number at 99 men plus Abbott himself.[21]

- ↑ On July 25 The Sun reported 25 idle ships docked for the loading of coal, eight to ten for oil, and "hundreds" of idle workers elsewhere in the city who would otherwise be employed loading coffee, salt and other goods.[23]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Stover, John (1995). History of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad. Purdue University Press.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Stowell, David. The Great Strikes of 1877. University of Illinois Press.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 Fifth Regiment Infantry, Md. Nat. Guard, U. S. Volunteer. A History of the Regiment from Its First Organization to the Present Time (PDF). Geo A. Meekins. 1889.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Wilson, Fredrick (1903). Federal Aid in Domestic Disturbances. 1787-1903. U.S. Government Printing Office.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 Dacus, Joseph (1877). Annals of the Great Strikes in the United States: A Reliable History and Graphic Description of the Causes and Thrilling Events of the Labor Strikes and Riots of 1877. L.T. Palmer.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 "The great railroad revolt" (PDF). The Sun. 22 July 2016. Retrieved 7 September 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Scharf, John (1879). History of Maryland. (PDF). John B. Piet.

- 1 2 3 4 "The war in Maryland" (PDF). The Sun. 23 July 1877. Retrieved 7 September 2016.

- ↑ Paul Kleppner, "The Greenback and Prohibition Parties," in Arthur M. Schlesinger (ed.), History of U.S. Political Parties: Volume II, 1860–1910, The Gilded Age of Politics. New York: Chelsea House/R.R. Bowker Co., 1973; pg. 1556.

- ↑ David Glasner, Thomas F. Cooley (1997). "Depression of 1873–1879". Business Cycles and Depressions: An Encyclopedia. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 0-8240-0944-4.

- ↑ Philip Mark Katz (1998). Appomattox to Montmartre: Americans and the Paris Commune. Harvard University Press. p. 167. ISBN 0-674-32348-3.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Laurie, Clayton (15 July 1997). The role of federal military forces in domestic disorders, 1877-1945. Government Printing Office.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 McCabe, James Dabney; Edward Winslow Martin (1877). The History of the Great Riots: The Strikes and Riots on the Various Railroads of the United States and in the Mining Regions Together with a Full History of the Molly Maguires.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "The Baltimore and Ohio R. R. Strike" (PDF). The Sun. 18 July 1877. Retrieved 6 September 2016.

- 1 2 3 "Labor troubles and disturbances" (PDF). The Sun. 17 July 1877. Retrieved 6 September 2016.

- 1 2 "The Baltimore and Ohio R. R. Strike" (PDF). The Sun. 19 July 1877. Retrieved 6 September 2016.

- 1 2 "A war on the railroads" (PDF). The Sun. 20 July 1877. Retrieved 6 September 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 "Railroad war in Maryland" (PDF). The Sun. 21 July 1877. Retrieved 7 September 2016.

- ↑ "Fayette Street bridge over Jones Falls, seen from north". Maryland Historical Society. Retrieved 1 September 2016.

- ↑ Shackelford, David. The Baltimore & Ohio Railroad in Maryland. Arcadia Publishing. p. 114.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "The railroad revolt" (PDF). The Sun. 26 July 1877. Retrieved 8 September 2016.

- 1 2 3 "The revolt on the railroads" (PDF). The Sun. 24 July 1877. Retrieved 7 September 2016.

- 1 2 "The general railroad strike" (PDF). The Sun. 25 July 1877. Retrieved 8 September 2016.

- 1 2 3 "The Great Railroad Revolt" (PDF). The Sun. 27 July 1877. Retrieved 8 September 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "The great railroad revolt" (PDF). The Sun. 28 July 1877. Retrieved 9 September 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Resumption of railroad traffic" (PDF). The Sun. 30 July 1877. Retrieved 9 September 2016.

- ↑ "The railroad transportation troubles" (PDF). The Sun. 31 July 1877. Retrieved 9 September 2016.

- ↑ "The striker's war subsiding" (PDF). The Sun. 1 August 1877. Retrieved 9 September 2016.

- ↑ Journal of Proceedings of the House of Delegates of Maryland, January Session, 1878 (PDF). George Colton. 1878.

- ↑ Susanne Moore (July 1985). "National Register of Historic Places Registration: Fifth Regiment Armory" (PDF). Maryland Historical Trust. Retrieved 2016-03-01.

- ↑ Shen, Fern (24 March 2013). "Epic railroad strike remembered with new Camden Yards plaque". Baltimore Brew. Retrieved 12 September 2016.

- ↑ Barry, Bill (5 March 2013). "New historic marker commemorates the 1877 Railroad Strike at Camden Station". Baltimore Heritage. Retrieved 12 September 2016.

External links

![]() Media related to Baltimore railroad strike of 1877 at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Baltimore railroad strike of 1877 at Wikimedia Commons

- "The Baltimore Railroad Strike & Riot of 1877: Archives of Maryland series". Maryland State Archives. Retrieved 1 September 2016.