Sama-Bajau peoples

| |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| At least 470,000 in the Philippines; At least 436,672 in Sabah, Malaysia;[1] 175,000 in Indonesia;[2] 12,000 in Brunei.[3] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

|

| |

| Languages | |

| Sinama,[4] Bajau, Tausūg, Zambaongueño Chavacano, Cebuano, Tagalog, Malay, Bugis, Indonesian and English | |

| Religion | |

|

Sunni Islam (majority), Folk Islam, Animism, Christianity | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

|

Yakan, Iranun, Tausūg, other Moros, Filipinos Malays, Bugis, and other wider Austronesian peoples |

The Sama-Bajau refers to several Austronesian ethnic groups of Maritime Southeast Asia with their origins from the southern Philippines. The name collectively refers to related people who usually call themselves the Sama or Samah; or are known by the exonyms Bajau (/ˈbɑːdʒaʊ, ˈbæ-/, also spelled Badjao, Bajaw, Badjau, Badjaw, Bajo or Bayao) and Samal or Siyamal (the latter being considered offensive). They usually live a seaborne lifestyle, and use small wooden sailing vessels such as the perahu (layag in Meranau), djenging, balutu, lepa, pilang, and vinta (or lepa-lepa).[5] Some Sama-Bajau groups native to Sabah are also known for their traditional horse culture.

The Sama-Bajau are traditionally from the many islands of the Sulu Archipelago in the Philippines, coastal areas of Mindanao, northern and eastern Borneo, the Celebes, and throughout eastern Indonesian islands.[6] In the Philippines, they are grouped together with the religiously-similar Moro people. Within the last 50 years, many of the Filipino Sama-Bajau have migrated to neighbouring Malaysia and the northern islands of the Philippines, due to the conflict in Mindanao.[7][8] As of 2010, they were the second-largest ethnic group in the Malaysian state of Sabah.[1][9]

Sama-Bajau have sometimes been called the "Sea Gypsies" or "Sea Nomads", terms that have also been used for non-related ethnic groups with similar traditional lifestyles, such as the Moken of the Burmese-Thai Mergui Archipelago and the Orang Laut of southeastern Sumatra and the Riau Islands of Indonesia. The modern outward spread of the Sama-Bajau from older inhabited areas seems to have been associated with the development of sea trade in sea cucumber (trepang).

Ethnonym

Like the term Kadazan-Dusun, Sama-Bajau is a collective term, used to describe several closely related indigenous people who consider themselves a single distinct bangsa ("ethnic group" or "nation").[5][10] It is generally accepted that these groups of people can be termed Sama or Bajau, though they never call themselves "Bajau" in the Philippines. Instead, they call themselves with the names of their tribes, usually the place they live or place of origin. For example, the sea-going Sama-Bajau prefer to call themselves the Sama Dilaut or Sama Mandilaut (literally "sea Sama" or "ocean Sama") in the Philippines; while in Malaysia, they identify as Bajau Laut.[11][12]

Historically in the Philippines, the term "Sama" was used to describe the more land-oriented and settled Sama–Bajau groups, while "Bajau" was used to describe the more sea-oriented, boat-dwelling, nomadic groups.[13] Even these distinctions are fading as the majority of Sama-Bajau have long since abandoned boat living, most for Sama–style piling houses in the coastal shallows.[12]

"Sama" is believed to have originated from the Austronesian root word sama meaning "together", "same", or "we".[14][15][16][17] The exact origin of the exonym "Bajau" is unclear. Some authors have proposed that it is derived from a corruption of the Malay word berjauh ("getting further apart" or "the state of being away").[17][18] Other possible origins include the Brunei Malay word bajaul, which means "to fish".[18] The term "Bajau" has pejorative connotations in the Philippines, indicating poverty in comparison to the term "Sama". Especially since it is used most commonly to refer to poverty-stricken Sama-Bajau who make a living through begging.[12]

British administrators in Sabah classified the Sama-Bajau as "Bajau" and labelled them as such in their birth certificates. Thus the Sama-Bajau in Malaysia may sometimes self-identify as "Bajau" or even "Malay" (though the preferred term is "Sama"), for political reasons. This is due to the government recognition of the Sama-Bajau as legally Bumiputera (indigenous native) under the name "Bajau".[12] This ensures easy access to the special privileges granted to ethnic Malays. This is especially true for recent Moro Filipino migrants. The indigenous Sama-Bajau in Malaysia have also started labelling themselves as their ancestors called themselves, such as Simunul.

History and origin

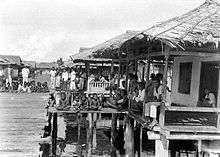

For most of their history, the Sama-Bajau have been a nomadic, seafaring people, living off the sea by trading and subsistence fishing.[20] The boat-dwelling Sama-Bajau see themselves as non-aggressive people. They kept close to the shore by erecting houses on stilts, and travelled using lepa, handmade boats which many lived in.[20]

Oral traditions

Most of the various oral traditions and tarsila (royal genealogies) among the Sama-Bajau have a common theme which claims that they were originally a land-dwelling people who were the subjects of a king who had a daughter. After she is lost by either being swept away to the sea (by a storm or a flood) or being taken captive by a neighbouring kingdom, they were then supposedly ordered to find her. After failing to do so they decided to remain nomadic for fear of facing the wrath of the king.[5][19][21][22]

One such version widely told among the Sama-Bajau of Borneo claims that they descended from Johorean royal guards who were escorting a princess named Dayang Ayesha for marriage to a ruler in Sulu. However, the Sultan of Brunei (allegedly Muhammad Shah of Brunei) also fell in love with the princess. On the way to Sulu, they were attacked by Bruneians in the high seas. The princess was taken captive and married to the Sultan of Brunei instead. The escorts, having lost the princess, elected to settle in Borneo and Sulu rather than return to Johor.[23][24]

Among the Indonesian Sama-Bajau, on the other hand, their oral histories place more importance on the relationship of the Sama-Bajau with the Sultanate of Gowa rather than Johor. The various versions of their origin myth tell about a royal princess who was washed away by a flood. She was found and eventually married a king or a prince of Gowa. Their offspring then allegedly became the ancestors of the Indonesian Sama-Bajau.[21][25]

However, there are other versions which are also more mythological and do not mention a princess. Among the Philippine Sama-Bajau, for example, there is a myth that claims that the Sama-Bajau were accidentally towed into what is now Zamboanga by a giant stingray.[5] Incidentally, the native pre-Hispanic name of Zamboanga City is "Samboangan" (literally "mooring place"), which was derived from the Sinama word for a mooring pole, sambuang or samboang.[24]

Modern research on origins

The origin myths claiming descent from Johor or Gowa have been largely rejected by modern scholars, mostly because these kingdoms were established too recently to explain the ethnic divergence.[22][24] Though whether the Sama-Bajau are indigenous to their current territories or settled from elsewhere is still contentious.[12] Linguistically, they are distinct from neighbouring populations, especially from the Tausūg who are more closely related to the northern Philippine ethnic groups like the Visayans.[5]

In 1965, the anthropologist David E. Sopher claimed that the Sama-Bajau, along with the Orang Laut, descended from ancient "Veddoid" (Australoid)[note 1] hunter-gatherers from the Riau Archipelago who intermarried with Austronesians. They retained their hunter-gatherer lifestyle, though they became more maritime-oriented as Southeast Asia became more populated by later Austronesian settlers like the Malays.[5]

In 1968, the anthropologist Harry Arlo Nimmo, on the other hand, believed that the Sama-Bajau are indigenous to the Sulu Archipelago, Sulawesi, and/or Borneo, and do not share a common origin with the Orang Laut. Nimmo proposed that the boat-dwelling lifestyle developed among the ancestors of the Sama-Bajau independently from the Orang Laut.[5]

A more recent study in 1985 by the anthropologist Alfred Kemp Pallasen compares the oral traditions with historical facts and linguistic evidence. He puts the date of the ethnogenesis of Sama-Bajau as 800 AD and also rejects a historical connection between the Sama-Bajau and the Orang Laut. He hypothesises that the Sama-Bajau originated from a proto-Sama-Bajau people inhabiting the Zamboanga Peninsula who practised both fishing and slash-and-burn agriculture. They were the original inhabitants of Zamboanga and the Sulu archipelago,[26] and were well-established in the region long before the first arrival of the Tausūg people at around the 13th century from their homelands along the northern coast of eastern Mindanao. Along with the Tausūg, they were heavily influenced by the Malay kingdoms both culturally and linguistically, becoming Indianised by the 15th century and Islamised by the 16th century.[27] They also engaged in extensive trade with China for "luxury" sea products like trepang, pearls, and shark fin.[10][27][28]

From Zamboanga, some members of this people adopted an exclusively seaborne culture and spread outwards in the 10th century towards Basilan, Sulu, Borneo, and Sulawesi.[27][29] They arrived in Borneo in the 11th century.[24] This hypothesis is currently the most widely accepted among specialists studying the Austronesian peoples. This would also explain why even boat-dwelling Sama-Bajau still practice agricultural rituals, despite being exclusively fishermen.[29] Linguistic evidence further points to Borneo as the ultimate origin of the proto-Sama-Bajau people.[10]

Historical records

The epic poem Darangan of the Maranao people record that among the ancestors of the hero Bantugan is a Maranao prince who married a Sama-Bajau princess. Estimated to have happened in 840 AD, it is the oldest account of the Sama-Bajau. It further corroborates the fact that they predate the arrival of the Tausūg settlers and are indigenous to the Sulu archipelago and parts of Mindanao.[22]

Sama-Bajau were first recorded by European explorers in 1521 by Antonio Pigafetta of the Magellan-Elcano expedition in what is now the present-day Zamboanga Peninsula. Pigafetta writes that the "people of that island make their dwellings in boats and do not live otherwise". They have also been present in the written records of other Europeans henceforth; including in Sulawesi by the Dutch colonies in 1675, in Sulawesi and eastern Borneo by Thomas Forrest in the 1770s,[5] and in the west coast of Borneo by Spenser St. John in the 1850s and 1860s.[23]

.jpg)

Sama-Bajau were often widely mentioned in connection to sea raids (mangahat), piracy and the slave trade in Southeast Asia during the European colonial period, indicating that at least some Sama-Bajau groups from northern Sulu (e.g. the Banguingui) were involved, along with non-Sama-Bajau groups like the Iranun. The scope of their pirate activities was extensive, commonly sailing from Sulu to as far as Moluccas and back again. Aside from early European colonial records, they may have also been the pirates described by Chinese and Arab sources in the Straits of Singapore in the 12th and 13th centuries.[27] Sama-Bajau usually served as low-ranking crewmembers of warboats, directly under the command of Iranun squadron leaders, who in turn answered to the Tausūg datu of the Sultanate of Sulu.[10]

The Bajoe harbour in Sulawesi was the site of a small settlement of Sama-Bajau under the Bugis Sultanate of Bone. They were significantly involved in First and Second Bone Wars (1824–1825), when the Royal Netherlands East Indies Army sent a punitive expedition in retaliation for Bugis and Makassar attacks on local Dutch garrisons. After the fall of Bone, most Sama-Bajau resettled in other areas of Sulawesi.[16][21]

During the British colonial rule of Sabah, the Sama-Bajau were involved in two uprisings against the North Borneo Chartered Company: the Mat Salleh Rebellion from 1894 to 1905, and the Pandasan Affair of 1915.[23]

Modern Sama-Bajau

Modern Sama-Bajau are generally regarded as peaceful, hospitable, and cheerful people, despite their humble circumstances. However, a significant number are also illiterate, uneducated, and impoverished, due to their nomadic lifestyle.[18]

The number of modern Sama-Bajau who are born and live primarily at sea is diminishing. Cultural assimilation and modernisation are regarded as the main causes.[5] Particularly after the dissolution of the Sultanate of Sulu, who were the traditional patrons of the Sama-Bajau for bartering fish for farm goods. The money-based fish markets which replaced the seasonal trade around mooring points necessitates a more land-based lifestyle for greater market penetration.[29] In Malaysia, some hotly debated government programs have also resettled Bajau to the mainland.[20]

The Sama-Bajau in the Sulu Archipelago were historically discriminated against by the dominant Tausūg people, who viewed boat-dwelling Sama-Bajau as 'inferior' and as outsiders (the traditional Tausūg term for them is the highly offensive Luwaan, meaning "spat out" or "outcast"). They were also marginalised by other Moro peoples because they still practised animist folk religions either exclusively or alongside Islam, and thus were viewed as "uncivilised pagans".[30] Boat-dwelling and shoreline Sama-Bajau had a very low status in the caste-based Tausūg Sultanate of Sulu.[24][26][31] This survived into the modern Philippines where the Sama-Bajau are still subjected to strong cultural prejudice from the Tausūg. The Sama-Bajau have also been frequent victims of theft, extortion, kidnapping, and violence from the predominantly Tausūg Abu Sayyaf insurgents as well as pirates.[10][32][33]

This discrimination and the continuing violence in Muslim Mindanao have driven many Sama-Bajau to emigrate. They usually resettle in Malaysia and Indonesia, where they have more employment opportunities.[34][35][36] But even in Malaysia their presence is still controversial as most of them are illegal immigrants. Most illegal Sama-Bajau immigrants enter Malaysia through offshore islands. From there, they enter mainland Sabah to find work as manual labourers.[7][10][37] Others migrate to the northern islands of the Philippines, particularly to the Visayas, Palawan, the northern coast of Mindanao, and even as far as southern Luzon.[15][17][18] Though these are relatively safer regions, they are also more economically disadvantaged and socially excluded, leading to Filipinos sometimes stereotyping the boat-dwelling Sama-Bajau as beggars and squatters.[10][12][18][38]

The ancestral roaming and fishing grounds of the Sama-Bajau straddled the borders of the Philippines, Malaysia, and Indonesia. And they have sometimes voyaged as far as the Timor and Arafura Seas.[39] In modern times, they have lost access to most of these sites. There have been efforts to grant Sama-Bajau some measures of rights to fish in traditional areas, but most Sama-Bajau still suffer from legal persecution. For example, under a 1974 Memorandum of Understanding, "Indonesian traditional fishermen" are allowed to fish within the Exclusive Economic Zone of Australia, which includes traditional fishing grounds of Sama-Bajau fishermen. However, illegal fishing encroachment of Corporate Sea Trawlers in these areas has led to concern about overfishing,[40] and the destruction of Sama-Bajau vessels.[39] In 2014, Indonesian authorities destroyed six Filipino Sama-Bajau boats caught fishing in Indonesian waters. This is particularly serious for the Sama-Bajau, whose boats are also oftentimes their homes.[41]

Sama-Bajau fishermen are often associated with illegal and destructive practices, like blast fishing, cyanide fishing, coral mining, and cutting down mangrove trees.[25][42] It is believed that the Sama-Bajau resort to these activities mainly due to sedentarisation brought about by the restrictions imposed on their nomadic culture by modern nation states. With their now limited territories, they have little alternative means of competing with better-equipped land-based and commercial fishermen, and earn enough to feed their families.[10][42] The Indonesian government and certain non-governmental organisations, have launched several programs for providing alternative sustainable livelihood projects for Sama-Bajau to discourage these practices (such as the use of fish aggregating devices instead of explosives).[25] Medical health centres (puskesmas) and schools have also been built even for stilt-house Sama-Bajau communities.[10] Similar programs have also been implemented in the Philippines.[43]

With the loss of their traditional fishing grounds, some refugee groups of Sama-Bajau in the Philippines are forced to resort to begging (agpangamu in Sinama), particularly diving for coins thrown by inter-island ferry passengers (angedjo). Other traditional sources of income include selling grated cassava (magliis), mat-weaving (ag-tepoh), and jewellery-making (especially from pearls). Recently, there have been more efforts by local governments in the Philippines to rehabilitate Sama-Bajau refugees and teach them livelihood skills.[18][30][44] In 2016, the Philippine Bureau of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources started a project for distributing fishing boats, gear, and other livelihood materials among Sama-Bajau communities in Luzon. This was largely the result of raised awareness and an outpouring of support after a photo of a Sama-Bajau beggar, Rita Gaviola (dubbed the "Badjao Girl"), went viral in the Philippines.[45][46][47]

Subgroups

The Sama-Bajau are fragmented into highly diverse subgroups. They have never been politically united and are usually subject to the land-based political groups of the areas they settle, such as the Sultanate of Brunei and the former Sultanate of Sulu.[29]

Most subgroups of Sama-Bajau name themselves after the place they originated from (usually an island).[24][26][29] Each subgroup speaks a distinct language or dialect that are usually mutually intelligible with their immediate neighbouring subgroup in a continuous linguistic chain.[29] In the Philippines, the Sama-Bajau can be divided into three general groups based on where they settle:[17][27]

- Sama Bihing or Sama Lipid - The "shoreline Sama" or "littoral Sama". These are the Sama-Bajau which traditionally lived in stilt houses in shallows and coastal areas. An example is the Sama Simunul. They are originally from the larger islands of Tawi-Tawi.[17][27] They have a more flexible lifestyle than the Sama-Gimba (Dilaut Origin), and will farm when there is available land. They usually act as middlemen in trade between the Sama Dilaut and other land-based peoples.[27]

- Sama Dea, Sama Deya, or Sama Darat - The "land Sama". These are the Sama-Bajau which traditionally lived in island interiors. Some examples are the Sama Sibutu and the Sama Sanga-Sanga. They are usually farmers who cultivate rice, sweet potato, cassava, and coconuts for copra through traditional slash-and-burn agriculture (in contrast to the plow agriculture technology brought by the Tausūg). They are originally from the larger islands of Tawi-Tawi and Pangutaran.[17][24][27] In the Philippines, the Sama Dea will often completely differentiate themselves from the Sama Dilaut.[48]

- Sama Dilaut, Sama Mandilaut or Bajau Laut - The "sea Sama" or "ocean Sama". In the Philippines, the preferred ethnonym is Sama Dilaut;[11] while in Malaysia, they usually identify as Bajau Laut. This subgroup originally lived exclusively on elaborately crafted houseboats called lepa, but almost all have taken to living on land in the Philippines. Their home islands include Sitangkai and Bongao.[49] They are the Sama-Bajau subgroup most commonly called "Bajau", though Filipino Sama Dilaut consider it offensive.[48] They sometimes call themselves the "Sama To'ongan" (literally "true Sama" or "real Sama"), to distinguish themselves from the land-dwelling Sama-Bajau subgroups.[14]

Other minor Sama-Bajau groups named after islands of origin include the Sama Bannaran, Sama Davao, Sama Zamboanga Sikubung, Sama Tuaran, Sama Semporna, Sama Sulawesi, Sama Simunul, Sama Tabawan, Sama Tandubas (or Sama Tando' Bas), and Sama Ungus Matata.[24] Mixed-heritage Sama-Bajau and Tausūg communities are sometimes known as "Bajau Suluk" in Malaysia.[7][50] People of multiple ethnic parentage may further identify with a three-part self-description, such as "Bajau Suluk Dusun".[51] The following are the major subgroups usually recognised as distinct:

- Bajo (Indonesia) - Also known as "Same'" (or simply "Sama") by the Bugis; and "Turijene" or "Taurije'n" (literally "people of the water"), "Bayo", or "Bayao" by the Makassar.[14][52] They are Sama-Bajau groups who settled in Sulawesi and Kalimantan, Indonesia through the Makassar Strait from as early as the 16th century.[5][53][54] They have spread further into nearby islands, including the Lesser Sunda Islands, Maluku Islands, and Raja Ampat Islands.[16]

- Banguingui (Philippines, Malaysia) - Also known as "Sama Balangingi" or "Sama Bangingi". Native to the Philippines. Some have recently migrated to Sabah. They are sometimes considered distinct from other Sama-Bajau. They have a more martial-oriented society, and were once part of regular sea raids and piracy against coastal communities and passing ships.[29][55] Main article: Banguingui people

- East Coast Bajau (Philippines, Malaysia) - are Sama Dilaut who settled in the eastern coast of Sabah, particularly around Semporna. They still identify themselves as Bajau Laut or Sama Laut. Though they are called East Coast Bajau to distinguish them from the Sama Kota Belud of western Sabah.[56] They are also known by the exonym "Pala'u" ("boat-dwelling" in Sinama), but it is sometimes considered derogatory. Some have retained their original boat-dwelling lifestyle, but many others have built homes on land. They are known for the colourful annual Regatta Lepa festival, which occurs from 24 to 26 April.[57]

- Jama Mapun (Philippines) - Also known as "Sama Kagayan". They are from the island of Mapun, Tawi-Tawi (formerly known as Cagayan de Sulu). Their culture is heavily influenced by the Sulu Sultanate.[58]

- Samal (Philippines, Malaysia) - "Samal" (also spelled "Siamal" or "Siyamal") is a Tausūg and Cebuano term and is sometimes considered offensive. Their preferred endonym is simply "Sama", and they are more accurately a general subgroup of Sama Dea ("land Sama") native to the Philippines.[14][48] A large number are now residing around the coasts of northern Sabah, though many have also migrated north to the Visayas and southern Luzon. They are predominantly land-dwelling.[5][36][48] They are the largest single group of Sama-Bajau.[59] In Davao del Norte, the Island Garden City of Samal was possibly named after them.[48][60]

- Ubian (Philippines, Malaysia) - Originated from the island of South Ubian in Tawi-Tawi, Philippines and make up the largest Sama-Bajau subgroup in Sabah. They reside in sizeable minorities living around the towns of Kudat and Semporna in Sabah, Malaysia.

- West Coast Bajau (Malaysia) - Also known as "Sama Kota Belud". Native to the western coast of Sabah, particularly around Kota Belud. They prefer to call themselves by the general ethnonym "Sama", not "Bajau"; and their neighbours, the Dusuns also call them "Sama". British administrators originally defined them as "Bajau". They are referred to as West Coast Bajau in Malaysia to distinguish them from the Sama Dilaut of eastern Sabah and the Sulu Archipelago.[56] They are known for having a traditional horse culture.[48]

- Yakan (Philippines) - Found in the traditional Sama-Bajau homelands of Zamboanga and surrounding islands (including Basilan). Though they may have been the ancestors of the Sama-Bajau, they have become linguistically and culturally distinct and are usually regarded as a separate ethnic group. They are exclusively land-based and are usually farmers.[29] Main article: Yakan people

Languages

The Sama–Bajau peoples speak some ten languages of the Sama–Bajau subgroup of the Western Malayo-Polynesian language family.[61] Sinama is the most common name for these languages, but they are also called Bajau, especially in Malaysia. The Tausūg people refer to these languages as Siamal.[11] Most Sama-Bajau can speak multiple languages.[10]

The Sama-Bajau languages were once classified under the Central Philippine languages of the Malayo-Polynesian geographic group of the Austronesian language family. But due to marked differences with neighbouring languages, they were moved to a separate branch altogether from all other Philippine languages.[62] For example, Sinama pronunciation is quite distinct from other nearby Central Philippine languages like Tausūg and Tagalog. Instead of the primary stress being usually on the final syllable; the primary stress occurs on the second-to-the-last syllable of the word in Sinama.[27] This placement of the primary stress is similar to Manobo and other languages of the predominantly animistic ethnic groups of Mindanao, the Lumad peoples.[63]

In 2006, the linguist Robert Blust, proposed that the Sama-Bajaw languages derived from the Barito lexical region, though not from any established group. It is thus a sister group to other Barito languages like Dayak and Malagasy. It is classified under the Bornean geographic group.[64]

Sama-Bajau languages are usually written in the Jawi alphabet.[15]

Culture

Religion

Religion can vary among the different Sama-Bajau subgroups; from a strict adherence to Sunni Islam, forms of folk Islam (itself influenced by Sufi traditions of early Muslim missionaries), to animistic beliefs in spirits and ancestor worship. There is a small minority of Catholics and Protestants, particularly from Davao del Sur in the Philippines.[22][30]

Among the modern coastal Sama-Bajau of Malaysia, claims to religious piety and learning are an important source of individual prestige. Some of the Sama-Bajau lack mosques and must rely on the shore-based communities such as those of the more Islamised or Malay peoples. Some of the more nomadic Sama-Bajau, like the Ubian Bajau, are much less adherent to orthodox Islam. They practice a syncretic form of folk Islam, also revering local sea spirits, known in Islamic terminology as Jinn.[29]

The ancient Sama-Bajau were animistic, and this is retained wholly or partially in some Sama-Bajau groups. The supreme deities in Sama-Bajau mythology are Umboh Tuhan (also known as Umboh Dilaut, the "Lord of the Sea") and his consort, Dayang Dayang Mangilai ("Lady of the Forest").[67] Umboh Tuhan is regarded as the creator deity who made humans equal with animals and plants. Like other animistic religions, they also fundamentally divide the world into the physical and spiritual realms which coexist together.[11][68] In modern Muslim Sama-Bajau, Umboh Tuhan (or simply Tuhan or Tuan) is usually equated with Allah.[24][68][note 2]

Other objects of reverence are spirits known as umboh ("ancestor", also spelled omboh or m'boh),[24] Traditionally, the umboh referred more specifically to ancestral spirits, different from the saitan (nature spirits) and the jinn (familiar spirits); though some literature refer to all of them as umboh.[69] These include Umboh Baliyu (the spirits of wind and storms), and Umboh Payi or Umboh Gandum (the spirits of the first rice harvest). They also include totemic spirits of various animals and plants, including Umboh Summut (totem of ants) and Umboh Kamun (totem of mantis shrimp).[68] The construction and launch of sailing vessels are also ritualised, and the vessels are believed to have a spirit known as Sumangâ ("guardian", literally "one who deflects attacks").[39] The umboh are believed to influence fishing activities, rewarding the Sama-Bajau by granting good luck favours known as padalleang and occasionally punishing by causing serious incidents called busong.[42][67]

Traditional Sama-Bajau communities may have shamans (dukun) traditionally known as the kalamat. The kalamat are also known in Muslim Sama-Bajau as the wali jinn (literally "custodian of jinn") and may adhere to taboos concerning the treatment of the sea and other cultural aspects. The kalamat preside over Sama-Bajau community events along with mediums known as igal jinn.[26][67] The kalamat and the igal jinn are said to be "spirit-bearers", and are actually believed to be hosts of familiar spirits. It is not, however, regarded as a spirit possession, since the igal jinn never lose control of their bodies. Instead, the igal jinn are believed to have acquired their familiar spirit (jinn) after surviving a serious or near-fatal illness. For the rest of their lives, the igal jinn are believed to share their bodies with the particular jinn who saved them.[67]

One important religious event among the Sama-Bajau is the annual feast known as pag-umboh or magpaay-bahaw, an offering of thanks to Umboh Tuhan.[24][26][29] In this ceremony, newly harvested rice (paay-bahaw) are dehusked (magtaparahu) while Islamic prayers (duaa) are recited. They are dried (magpatanak) and are then laid out in small conical piles symbolic of mountains (bud) on the living room floor (a process known as the "sleeping of rice"). After two or three nights, two-thirds are set aside for making sweet rice meals (panyalam), while one-third is set aside for making sweet rice cakes (durul).[26][29] Additional prayers (zikir), which includes calling the names of ancestors out loud, are offered to the Umboh after the rice meals have been prepared. Pag-umboh is a solemn and formal affair.[26]

Another annual religious ceremony among the boat-dwelling Sama Dilaut is the pagkanduli (literally "festive gathering").[69] It involves ritual dancing to Umboh Tuhan, Dayang Dayang Mangilai, and ancestral ghosts called bansa. The ritual is first celebrated under a sacred dangkan tree (strangler figs, known elsewhere in the Philippines as balete) symbolising the male spirit Umboh Tuhan; and afterwards in the centre of a grove of kama'toolang trees (pandan trees) symbolising the female spirit Dayang Dayang Mangilai.[67]

The trance dancing is called mag-igal and involves female and male and igal jinn, called the jinn denda and jinn lella respectively. The jinn denda perform the first dance known as igal limbayan under the dangkan tree, with the eldest leading. They are performed with intricate movements of the hands, usually also with metal fingernail extensions called sulingkengkeng. If the dance and music are pleasing, the bansa are believed to take actual possession of the dancers, whereupon the wali jinn will assist in releasing them at the end of the dance. The bansa are not feared, however, as they are regarded as actual spirits of ancestors. Temporarily serving as hosts for the bansa while dancing to music is regarded as a "gift" by the living Sama Dilaut to their ancestors. After the igal limbayan, the wali jinn will invite the audience to participate, to celebrate and to give their thanks. The last dance is the igal lellang, with four jinn lella performing a warrior dance, whereupon the participants will proceed to the kama'toolang grove. There they will also perform rituals and dance (this time with both male and female dancers together), symbolically "inviting" Dayang Dayang Mangilai to come with them back to the dangkan tree. Further games and celebrations are held under the original dangkan tree before the celebrants finally say their farewells to the spirits. Unlike pag-umboh, pagkanduli is a joyous celebration, involving singing, dancing, and joking among all participants. It is the largest festive event among the Sama Dilaut communities.[26]

Aside from pagkanduli and magpaay-bahaw, public dances called magigal jinn may also occur at various times of the year. During these celebrations, the igal jinn may be consulted for a public séance and for nightly trance dancing.[69] In times of epidemics, the igal jinn are also called upon to remove illness causing spirits from the community. They do this by setting a "spirit boat" adrift in the open sea beyond the village or anchorage.

Boat-dwelling

A few Sama-Bajau still live traditionally. They live in houseboats which generally accommodates a single nuclear family (usually five people). The houseboats travel together in flotillas with houseboats of immediate relatives (a family alliance) and co-operate during fishing expeditions and in ceremonies. A married couple may choose to sail with the relatives of the husband or the wife. They anchor at common mooring points (called sambuangan) with other flotillas (usually also belonging to extended relatives) at certain times of the year.[24][23][29]

These mooring points are usually presided over by an elder or headsman. The mooring points are close to sources of water or culturally significant locations like island cemeteries. There are periodic gatherings of Sama-Bajau clans usually for various ceremonies like weddings or festivals. They generally do not sail more than 40 km (24.85 mi) from their "home" moorage.[5][23] They periodically trade goods with the land-based communities of other Sama-Bajau and other ethnic groups.[23] Sama-Bajau groups may routinely cross the borders of the Philippines, Malaysia, and Indonesia for fishing, trading, or visiting relatives.[12][18][24][70]

Sama-Bajau are also noted for their exceptional abilities in free-diving, with physical adaptations that enable them to see better and dive longer underwater.[71] Divers work long days with the "greatest daily apnea diving time reported in humans" of greater than 5 hours per day submerged.[72] Some Bajau intentionally rupture their eardrums at an early age to facilitate diving and hunting at sea. Many older Sama-Bajau are therefore hard of hearing.[20][71] Sama-Bajau women also use a traditional sun-protecting powder called burak or borak, made from water weeds, rice and spices.[73]

Music, dance, and arts

Sama-Bajau traditional songs are handed down orally through generations. The songs are usually sung during marriage celebrations (kanduli pagkawin), accompanied by dance (pang-igal) and musical instruments like pulau (flute), gabbang (xylophone), tagunggo' (kulintang gongs), and in modern times, electronic keyboards.[26] There are several types of Sama-Bajau traditional songs, they include: isun-isun, runsai, najat, syair, nasid, bua-bua anak, and tinggayun.[14][74]

Among the more specific examples of Sama-Bajau songs are three love songs collectively referred to as Sangbayan. These are Dalling Dalling, Duldang Duldang, and Pakiring Pakiring.[26] The most well-known of these three is Pakiring Pakiring (literally "moving the hips"), which is more familiar to the Tausūg in its commercialised and modernised form Dayang Dayang. The Tausūg claim that the song is native to their culture, and whether the song is originally Tausūg or Sama-Bajau remain controversial.[26] Most Sama-Bajau folk songs are becoming extinct, largely due to the waning interest of the younger generations.[14]

Sama-Bajau people are also well known for weaving and needlework skills.

Horse culture

The more settled land-based West Coast Bajau are expert equestrians – which makes them remarkable in Malaysia, where horse riding has never been widespread anywhere else. The traditional costume of Sama-Bajau horsemen consists of a black or white long-sleeved shirt (badu sampit) with gold buttons (betawi) on the front and decorated with silver floral designs (intiras), black or white trousers (seluar sampit) with gold lace trimmings, and a headpiece (podong). They carry a spear (bujak), a riding crop (pasut), and a silver-hilted keris dagger. The horse is also caparisoned with a colourful outfit called kain kuda that also have brass bells (seriau) attached. The saddle (sila sila) is made from water buffalo hide, and padded with cloth (lapik) underneath.[75]

Society

Though some Sama-Bajau headsmen have been given honorific titles like "datu", "maharaja" or "panglima" by governments (like under the Sultanate of Brunei), they usually only had little authority over the Sama-Bajau community. Sama-Bajau society is traditionally highly individualistic,[23] and the largest political unit is the clan cluster around mooring points, rarely more. Unlike most neighbouring peoples, Sama-Bajau society is also more or less egalitarian, and they did not practice a caste system. The individualism is probably due to the generally fragile nature of their relationships with land-based peoples for access to essentials like wood or water. When the relationship sours or if there is too much pressure from land-based rulers, the Sama-Bajau prefer to simply move on elsewhere.[27] Greater importance is placed on kinship and reciprocal labour rather than formal authority for maintaining social cohesion.[18] There are a few exceptions, however, like the Jama Mapun and the Sama Pangutaran of the Philippines, who follow the traditional pre-Hispanic Philippine feudal society with a caste system consisting of nobles, notables, and commoners and serfs. Likely introduced by the Sultanate of Sulu.[23]

Depictions in popular culture

.svg.png)

It has been suggested by some researchers that Sama-Bajau people's visits to Arnhem Land gave rise to the accounts of the mysterious Baijini people in the myths of Australia's Yolngu Aboriginals.[77]

The Sama-Bajau have also been the subject of several films. They include:

- Badjao (1957) - A Filipino film directed by Lamberto V. Avellan

- Bajau Laut: Nomads of the Sea (2008) - A Singaporean TV documentary produced by Matthew Malpelli.

- The Mirror Never Lies (2011) Indonesian film directed by Kamila Andini

- Thy Womb (2012) - A Filipino drama film directed by Brillante Mendoza

- Bohe': Sons of the Waves (2013) - A Filipino short film produced by Nadjoua and Linda Bansil

- Anak ng Badjao (1987) - A Filipino Film directed by Jose Antonio Alonzo and Jerry O. Tironazona

Notable Sama-Bajau

Politics

- Mat Salleh (Datu Muhammad Salleh) - Sabah warrior from Inanam, Kota Kinabalu during the British administration of North Borneo.

- Tun Datu Mustapha (Tun Datu Mustapha bin Datu Harun) - The first Yang di-Pertua Negeri (Governor) of Sabah and the third Chief Minister of Sabah from Kudat.

- Tun Said Keruak (Tun Muhammad Said Keruak) - The seventh Governor of Sabah and the fourth Chief Minister of Sabah from Kota Belud.

- Tun Sakaran Dandai - The eighth Governor of Sabah and also the eighth Chief Minister of Sabah from Semporna.

- Ahmadshah Abdullah - The ninth Governor of Sabah from Inanam, Kota Kinabalu.

- Salleh Said Keruak (Datuk Seri Panglima Mohd Salleh bin Tun Mohd Said Keruak) - The ninth Chief Minister of Sabah from Kota Belud and currently a federal minister with the rank of Senator in the Dewan Negara.

- Osu Sukam (Datuk Seri Panglima Osu bin Sukam) - The twelfth Chief Minister of Sabah from Papar.

- Mohd Nasir Tun Sakaran (Dato' Mohd Nasir bin Tun Sakaran Dandai) - Sabah politician from Semporna.

- Shafie Apdal (Dato' Seri Hj Mohd Shafie Bin Apdal) - Former Malaysian minister from Semporna.

- Pandikar Amin Mulia - Speaker of the Dewan Rakyat, Member of Parliament of Malaysia from Kota Belud.

- Askalani Abdul Rahim (Datuk Askalani Bin Abdul Rahim) - Former Minister of Culture, Youth and Sports from Semporna.

Entertainment

- Adam AF2 (Aizam Mat Saman) - Malaysian singer and actor, nephew of Tun Ahmadshah Abdullah.

- Sitti - Filipino singer.

- Yanie (Mentor) (the late Siti Suriane Julkarim)[78] - Malaysian singer in the popular TV shows of Mentor on TV3 from Kota Kinabalu.

- Wawa Zainal Abidin - Malaysian actress.

- Azwan Kombos - Malaysian actor.[79][80]

- Rita Gabiola - Filipino actress in the Pinoy Big Brother Season 7.[81]

Sports

- Bana Sailani - A Filipino Olympic swimmer who represented the Philippines in the 1956 Summer Olympics, the 1958 Asian Games (where he won 5 bronze medals, and 1 silver), and the 1960 Summer Olympics. He was more popularly known as Bapa' Banana.[82]

- Estino Taniyu - A Malaysian swimmer from the Royal Malaysian Navy who swam across the English Channel in 13 hours, 45 minutes, and 45 seconds on 21 September 2012.[83]

- Matlan Marjan - Former Malaysian football player and the former Sabah FA captain.

See also

Notes

- ↑ The concept of an Australoid "race" is antiquated. Most modern literature refer to these peoples as the Australo-Melanesians. However, their exact relationship within their member groups and with other ethnic groups in Asia and Oceania is still debated.

- ↑ Tuhan is a common word referring to a supreme deity in various Austronesian languages in eastern Malaysia, southwestern Philippines, and eastern Indonesia. It originally referred to a different concept of a deity separate from the Abrahamic god, but Malays and other Muslim Austronesian ethnic groups usually equate Tuhan with Allah. Compare with Bathala of the Tagalogs and Kan-Laon of the Visayans.

References

- 1 2 "Total population by ethnic group, administrative district and state, Malaysia" (PDF). Department of Statistics, Malaysia. 2010. pp. 369/1. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 February 2012. Retrieved 12 October 2014.

- ↑ https://joshuaproject.net/people_groups/10582/ID

- ↑ https://joshuaproject.net/people_groups/12978/BX

- ↑ "What Language do the Badjao Speak?". Kauman Sama Online. Sinama.org. Retrieved 23 February 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Harry Nimmo (1972). The sea people of Sulu: a study of social change in the Philippines. Chandler Pub. Co. ISBN 0-8102-0453-3.

- ↑ Lotte Kemkens. Living on Boundaries: The Orang Bajo of Tinakin Laut, Indonesia (PDF) (Social Anthropology Bachelor's thesis). University of Utrecht. Retrieved 21 March 2011.

- 1 2 3 Catherine Allerton (5 December 2014). "Statelessness and child rights in Sabah". New Mandala. Retrieved 22 December 2014.

- ↑ "The Bajau, the Badjao, the Samals, and the Sama People". Retrieved 3 December 2012.

- ↑ "Sabah's People and History". Sabah State Government. Retrieved 25 March 2015.

The Kadazan-Dusun is the largest ethnic group in Sabah that makes up almost 30% of the population. The Bajaus, or also known as "Cowboys of the East", and Muruts, the hill people and head hunters in the past, are the second and third largest ethnic group in Sabah respectively. Other indigenous tribes include the Bisaya, Brunei Malay, Bugis, Kedayan, Lotud, Ludayeh, Rungus, Suluk, Minokok, Bonggi, the Ida'an, and many more. In addition to that, the Chinese makes up the main non-indigenous group of the population.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Tom Gunnar Hoogervorst (2012). "Ethnicity and aquatic lifestyles: exploring Southeast Asia's past and present seascapes" (PDF). Water History. 4: 245–265. doi:10.1007/s12685-012-0060-0.

- 1 2 3 4 Nimfa L. Bracamonte (2005). "Evolving a Development Framework for the Sama Dilaut in an Urban Center in the Southern Philippines". Borneo Research Bulletin. 36: 185.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Kazufumi Nagatsu (2001). "Pirates, Sea Nomads or Protectors of Islam?: A Note on "Bajau" Identifications in the Malaysian Context" (PDF). アジア・アフリカ地域研究. 1: 212–230.

- ↑ G.N. Appell (1969). "Studies of the Tausug (Suluk( and Samal-speaking populations of Sabah and the southern Philippine islands" (PDF). Borneo Research Bulletin. 1 (2): 21–23.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Saidatul Nornis Haji Mahali (2008). "Tinggayun: Implications of Dance and Song in Bajau Society". In Merete Falck Borch; Eve Rask Knudsen; Martin Leet; Bruce Clunies Ross. Bodies and Voices: The Force-field of Representation and Discourse in Colonial and Postcolonial Studies. Cross/Cultures 94. Rodopi. pp. 153–161. ISBN 9789042023345.

- 1 2 3 "Bahasa Sama-Bajaw: Sama Bajau (Sama-Badjao) Varieties". Lowlands-L. 2011. Retrieved 20 December 2014.

- 1 2 3 Horst Liebner (2012). "A Princess Adrift: Bajau Origins, animated MSPowerpoint show, for a conference at Tanjung Pinang, 2012". East Asian Studies, University of Leeds. Retrieved 20 December 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Ethnographic Reading of Silungan Baltapa: Ancestral Tradition and Sufic Islam Values of Sama Bajau". iWonder. 21 October 2013. Retrieved 20 December 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Nimfa L. Bracamonte; Astrid S. Boza & Teresita O. Poblete (2011). "From the Seas to the Streets: The Bajau in Diaspora in the Philippines". IPEDR Vol. 20 (PDF). 2011 International Conference on Humanities, Society and Culture. pp. 287–291.

- 1 2 David E. Sopher (1965). "The Sea Nomads: A Study Based on the Literature of the Maritime Boat People of Southeast Asia". Memoirs of the National Museum. 5: 389–403. doi:10.2307/2051635.

- 1 2 3 4 "The last of the sea nomads". The Guardian. 18 September 2010. Archived from the original on 18 September 2010. Retrieved 18 September 2010.

- 1 2 3 Horst Liebner (1996). Four Oral Versions of a Story about the Origin of the Bajo People of Southern Selayar (PDF). Proyek Pengkajian dan Pengembangan Masyarakat Pantai, YIIS UNHAS. Wissenschaftlich-Literarischer Selbst- und Sonderverlach.

- 1 2 3 4 Mucha-Shim Lahaman Quiling (2012). Mbal Alungay Bissala: Our Voices Shall Not Perish - Listening, Telling, Writing of the Sama Identity and Its Political History in Oral Narratives (PDF). The Work of 2011/2012 API Fellows. The Nippon Foundation Fellowships for Asian Public Intellectuals. pp. 141–148.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Mark T. Miller (2011). Social Organization of the West Coast Bajau (PDF). SIL International.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Rodney C. Jubilado; Hanafi Hussin & Maria Khristina Manueli (2011). "The Sama-Bajaus of Sulu-Sulawesi Seas: perspectives from linguistics and culture" (PDF). Journal of Southeast Asian Studies. 15 (1): 83–95.

- 1 2 3 Syamsul Huda M. Suhari (7 June 2013). "Bajo, past and present". The Jakarta Post. Retrieved 21 December 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Rodney C. Jubilado (2010). "On cultural fluidity: The Sama-Bajau of the Sulu-Sulawesi Seas". Kunapipi. 32 (1): 89–101.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Alfred Kemp Pallasen (1985). Culture Contact and Language Convergence (PDF). LSP Special Monogaph Issue 24. Linguistic Society of the Philippines.

- ↑ Brad Bernard (6 March 2014). "The Secret Lives of Bajau Sea Gypsies: A True Account". myWanderlist. Retrieved 20 December 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Clifford Sather (2006). "Sea Nomads and Rainforest Hunter-Gatherers: Foraging Adaptations in the Indo-Malaysian Archipelago - The Sama-Bajau". In Peter Bellwood; James J. Fox; Darrell Tryon. The Austronesians: Historical and Comparative Perspectives. ANU E Press. pp. 257–264. ISBN 9781920942854.

- 1 2 3 Waka Aoyama (2014). To Become "Christian Bajau": The Sama Dilaut’s Conversion to Pentecostal Christianity in Davao City, Philippines (PDF). Harvard-Yenching Institute Working Paper Series. Institute for Advanced Studies on Asia, The University of Tokyo.

- ↑ Harry Arlo Nimmo (1968). "Reflections on Bajau History". Philippine Studies: Historical and Ethnographic Viewpoints. 16 (4): 32–59.

- ↑ "Bajau Laut of Semporna: Peaceful Nomads or Fish Bombers?". Amana': Empowering the Outcasts. 4 December 2012. Retrieved 22 December 2014.

- ↑ Artchil C. Daug, Christopher O. Kimilat, Glory Grace Ann G. Bayon, & Angenel Clariz D. Rufon (2013). The Possibility of Ethnogenesis of the Badjao in Barangay Tambacan, Iligan City. The International Conferences on Social Sciences Research.

- ↑ Mellie Leandicho Lopez (2006). A handbook of Philippine folklore. UP Press. p. 50. ISBN 971-542-514-3.

- ↑ Twilight of the Sea People, Vol. III (2), Philippine Center of Investigative Journalism, June 2001, retrieved 21 March 2011

- 1 2 Edsel L. Beja (2006). Negotiating globalization in Asia. Ateneo de Manila University Press. p. 286. ISBN 971-0426-01-X.

- ↑ "RCI report: Who are the illegals?". The Star. 4 December 2014. Retrieved 22 December 2014.

- ↑ "Little People Waging Big Battles: A HealthGov Story". MindaNews. 8 July 2007. Retrieved 22 December 2014.

- 1 2 3 Stacey, Natasha (2007). Boats to Burn: Bajo fishing activity in the Australian fishing zone (PDF). Canberra, Australia: ANU E Press. ISBN 978-1-920942-95-3.

- ↑ Field, I.C., Meekan, M.G., Buckworth, R.C., Bradshaw, C.J.A. (2009). "Protein mining the world's oceans: Australasia as an example of illegal expansion-and-displacement fishing". Fish and Fisheries. 10: 323–328. doi:10.1111/j.1467-2979.2009.00325.x.

- ↑ Jamil Maidan Flores (14 December 2014). "Bajau Fishers: A Plea for Tempering Justice with Mercy". Jakarta Globe. Retrieved 22 December 2014.

- 1 2 3 Julian Clifton & Chris Majors (2012). "Culture, conservation, and conflict: perspectives on marine protection among the Bajau of Southeast Asia" (PDF). Society & Natural Resource: An International Journal. 25 (7): 716–725. doi:10.1080/08941920.2011.618487.

- ↑ "Sama-Bajau fishermen taught the do's and don'ts of coastal conservation". Zamboanga Times. 25 November 2012. Retrieved 22 December 2014.

- ↑ Glenn Lopez (18 December 2013). "DSWD-NCR Assists Sama Bajau in Metro Manila". Department of Social Welfare and Development, Republic of the Philippines. Retrieved 22 December 2013.

- ↑ Delfin T. Mallari, Jr. (2 June 2016). "'Badjao Girl' thanks Allah for family's new life, blessings". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Retrieved 20 June 2016.

- ↑ Monet Lu (28 May 2016). "Meet the Filipino 'instant celebrities' of Social Media". Asian Journal. Retrieved 20 June 2016.

- ↑ "Viral: 'Badjao Girl' finds hope in internet fame". Coconuts Manila. 26 May 2016. Retrieved 20 June 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Kauman Sama Online". Kauman Sama Online. Sinama.org. Retrieved 20 December 2014.

- ↑ "Sama". National Commission for Culture and the Arts, Government of the Philippines. Retrieved 18 December 2014.

- ↑ Patricia C, Almada-Villela (2002). "Pilot Fisheries Socio-economic Survey of Two Coastal Areas in Eastern Sabah". In Sarah L. Fowler; Tim M. Reed; Frances Dipper. Elasmobranch Biodiversity, Conservation and Management: Proceedings of the International Seminar and Workshop, Sabah, Malaysia, July 1997. IUCN Species Survival Commission. p. 36. ISBN 9782831706504.

- ↑ Graham K. Brown (2014). "Legible Pluralism: The Politics of Ethnic and Religious Identification in Malaysia". In Joseph B. Ruane; Jennifer Todd. Ethnicity and Religion: Intersections and Comparisons. Routledge. p. 37. ISBN 9781317982852.

- ↑ https://www.ethnologue.com/language/bdl

- ↑ Robert Cribb (2010). "Bajau Laut settlements in Kalimantan and Sulawesi". Digital Atlas of Indonesian History. Retrieved 18 December 2014.

- ↑ Manusia Bugis, Christian Pelras, ISBN 979-99395-0-X, translated from "The Bugis", Christian Pelras, 1996, Oxford:Blackwell Publishers Ltd.

- ↑ James Francis Warren (2007). The Sulu zone, 1768–1898: the dynamics of external trade, slavery, and ethnicity in the transformation of a Southeast Asian maritime state. NUS Press. p. 184. ISBN 9971-69-386-0.

- 1 2 Mark T. Miller (2007). A Grammar of West Coast Bajau. ProQuest. pp. 7–8. ISBN 9780549145219.

- ↑ "Pesta Regatta Lepa Semporna". Sabah Tourism Board, Malaysia Government. Retrieved 20 December 2014.

- ↑ "Jama Mapun". National Commission for Culture and the Arts, Government of the Philippines. Retrieved 18 December 2014.

- ↑ "Samal – Orientation". Countries and Their Cultures. Retrieved 17 June 2011.

- ↑ "About Samal". Visit Samal Island. Department of Tourism, Government of the Philippines. Retrieved 21 December 2014.

- ↑ Clifford Sather, "The Bajau Laut", Oxford U. Press, 1997

- ↑ "Samal - Orientation". Countries and Their Cultures. Retrieved 20 December 2014.

- ↑ Carl D. Dubois (1976). "Sarangani Manobo" (PDF). Philippine Journal of Linguistics. Special Monograph Issue. 6: 1–166.

- ↑ Robert Blust (2006). "The linguistic macrohistory of the Philippines". In Hsiu-chuan Liao; Carl R. Galvez Rubino. Current Issues in Philippine Linguistics and Anthropology: parangal kay Lawrence A. Reid. Linguistic Society of the Philippines and SIL Philippines. pp. 31–68. ISBN 9789717800226.

- ↑ "2010 Population and Housing Census of Malaysia" (PDF) (in Malay and English). Department of Statistics, Malaysia. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 October 2012. Retrieved 17 June 2012. p. 107

- ↑ "Masjid An-Nur Tuaran". Islamic Tourism Centre of Malaysia. Archived from the original on 12 August 2016. Retrieved 12 August 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Hanafi Hussin & MCM Santamaria (2008). "Dancing with the ghosts of the sea: Experiencing the Pagkanduli ritual of the Sama Dilaut (Bajau Laut) in Sikulan, Tawi-Tawi, Southern Philippines" (PDF). JATI: Jurnal Jabatan Pengajian Asia Tenggara Fakulti Sastera Dan Sains Sosial. 13: 159–172.

- 1 2 3 "Exploration into Sama Philosophy: OMBOH". Limpah Tangan [BELIEVE]. Retrieved 18 December 2014.

- 1 2 3 Hanafi Hussin (2010). "Balancing the Spiritual and Physical Worlds: Memory, Responsibility, and Survival in the Rituals of the Sama Dilaut (Bajau laut) in Sitangkai, Tawi-Tawi, Southern Philippines and Semporna, Sabah, Malaysia". In Birgit Abels; Morag Josephine Grant; Andreas Waczkat. Oceans of Sound: Sama Dilaut Performing Arts (PDF). Göttinger Studien zur Musikwissenschaft Volume 3.

- ↑ Lucio Blanco Pitlo III (29 May 2013). "The Philippine-Malaysian Sabah Dispute". Sharnoff's Global News. Retrieved 18 December 2014.

- 1 2 Megan Lane (12 January 2011), What freediving does to the body, BBC News, archived from the original on 18 March 2011, retrieved 21 March 2011

- ↑ Schagatay E; Lodin-Sundström A; Abrahamsson E (March 2011). "Underwater working times in two groups of traditional apnea divers in Asia: the Ama and the Bajau". Diving and Hyperbaric Medicine. 41 (1): 27–30. PMID 21560982. Retrieved 14 June 2013.

- ↑ Berta Tilmantaite (20 March 2014). "In Pictures: Nomads of the sea". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 22 December 2014.

- ↑ Inon Shaharuddin A. Rahman (2008). Three Singers: The Keepers of Tradition (PDF). ASEAN Committee on Culture and Information.

- ↑ Lailawati Binti Madlan; Chua Bee Seok; Jasmin Adela Mutang; Shamsul Amri Baharudin & Ho Cheah Joo (2014). "The Prejudice of Bajau: From Own and Others Ethnic Perspective: A Preliminary Study in Sabah" (PDF). International Journal of Information and Education Technology. 4 (3): 244–248. doi:10.7763/IJIET.2014.V4.406.

- ↑ Ian MacDonald. "Sabah (Malaysia)". CRW Flags. Archived from the original on 25 May 2016. Retrieved 25 May 2016.

- ↑ Berndt, Ronald Murray; Berndt, Catherine Helen (1954). "Arnhem Land: its history and its people". Volume 8 of Human relations area files: Murngin. F. W. Cheshire: 34.

- ↑ Kemalia Othman (22 March 2010). "Jenazah Yanie (Mentor) Selamat Disemadikan" (in Malay). mStar. Retrieved 20 August 2016.

- ↑ Zulqarnain Abu Hassan (16 March 2016). "Azwan Kombos Mahu Kahwin Pakai Baju Bajau" (in Malay). Media Hiburan. Retrieved 20 August 2016.

- ↑ Zaidi Mohamad (15 June 2016). "Ezzaty, Azwan Kombos nikah 16 Julai" (in Malay). Berita Harian. Retrieved 20 August 2016.

- ↑ "'Badjao Girl' Rita Gabiola gets a makeover — see her amazing new look!". Zeibiz. 29 May 2016. Retrieved 20 August 2016.

- ↑ Maica Bailon (13 May 2003). "Alligator in the pool". Philstar. Retrieved 22 December 2014.

- ↑ "Semporna welcomes home English Channel swimmer". The Borneo Post. 7 October 2012. Retrieved 22 December 2014.

Further reading

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bajau people. |

Newspapers

- Journey in Borneo with Bajaus by Réhahn

- Bajaus Children at the Daily Mail

- More information on the Bajaus at the BBC

- The last of the sea nomads at The Guardian

- The sea gypsies of Sulu at the Khaleej Times

Books

- François-Robert Zacot (2009). "Peuple nomade de la mer ,les Badjos d'Indonésie", éditions Pocket, collection Terre Humaine, Paris