Bach quadrangle

The Bach quadrangle encompasses the south polar part of Mercury poleward of latitude 65° S.

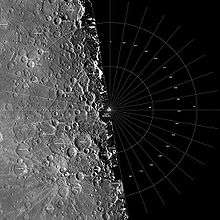

Mariner 10 photography

About half of the region was beyond the terminator during the three Mariner 10 encounters and hence not visible. The entire mapped area was covered by near-vertical photography from the second encounter, and the eastern part, from longitude 15° to about 110°, was covered by oblique photography from the first encounter. No third-encounter images were acquired. The entire visible area may be viewed stereoscopically by combining images from the first and second encounters taken at different viewing angles or by combining second-encounter images of the same area taken at different viewing angles. These combinations provided excellent qualitative control of topographic relief and a good quantitative photogrammetric base. However, sun-elevation angles of the images are limited to less than 25°, and image resolutions are no higher than about 0.5 km per picture element. Therefore, the south polar geologic map reflects mostly large-scale processes and topographic information, whereas other mercurian quadrangle maps benefit from greater albedo discrimination and, in some cases, higher resolution.

The imaged part of the Bach region covers about 1,570,000 km2. Its surface consists of craters of a wide variety of sizes and morphologies, as well as plains units, fault scarps, and ridges. It includes three double-ring basins that range from 140 to 200 km in diameter: Bach (after which the region is named), Cervantes, and Bernini. Another large crater, Pushkin, is 240 km in diameter and occurs at the map boundary at latitude 65° S., longitude 25° . Both Bach and Bernini display extensive fields of secondary craters. An unusual area between lat 69° and 80° S. and long 30° and 60° consists of young, relatively smooth plains marked by many flat-topped ridges unlike any seen in other areas of Mercury. Scarps similar to Discovery Rupes (in the Discovery quadrangle adjacent to the north) are relatively common throughout the Bach region. The most common terrain units in the region are the plains units, which display a wide range of small-crater densities.

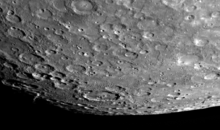

MESSENGER photography

During MESSENGER's January 14, 2008 flyby, the probe photographed previously unseen portions of this region.

Stratigraphy

Crater and basin materials

Superposition relations among craters and basins, and their ejecta, provide the best means of establishing the relative time-stratigraphic order of crater and basin materials. Relative to the Moon, stratigraphic relations among mercurian craters are more clearly discerned because Mercury has a lower density of large craters,[1] and its enhanced gravitational acceleration has restricted the distribution of ejecta.[2] These attributes of the mercurian crater population allow stratigraphic sequences to be constructed over large regions.

The degree of crater degradation is determined by qualitative assessment of their landforms such as rim crests, interior wall terraces and slumps, central peaks, continuous ejecta deposits, and secondary crater fields (see Malin and Dzurisin, 1977; McCauley and others, 1981). To the extent that degradational changes are systematic with increasing age, they can be used to correlate local and regional stratigraphic sequences over the map region. On the basis of this morphologic evaluation, five crater ages are defined and used to make stratigraphic assignments. However, the low sun angle at which images in the region were acquired may make craters appear younger than in other parts of Mercury where images were taken at higher sun angles.

Of the region’s three double-ring basins, Bach (200 km in diameter) and Bernini (140 km in diameter) are moderately fresh (of c3 age) and have well-defined secondary-crater fields, whereas Cervantes (200 km in diameter) is degraded (c1). The inner rings of the three basins are about half the diameter of the outer rings. Bach’s inner ring, the most complete, is open only to the southeast; it consist of an almost continuous series of sharp-crested hills. The area within it and part of the area between it and the outer ring are filled with smooth plains material. The inner rings of Cervantes and Bernini consist of discontinuous, low, rounded hills, Bernini has a small central peak.

As first noted by Gault and others,[2] the continuous ejecta blankets and secondary crater fields surrounding mercurian craters are smaller than their lunar counterparts, and the boundary between the two features is much less distinct. As a consequence, continuous and discontinuous ejecta are mapped together in the Bach region as “radial facies.” With this exception, the morphological elements of mercurian craters are virtually identical with those on the Moon. Therefore, all of the craters within the Bach region are probably the result of impact by meteorites, small planetesimals, and possibly comets.

Plains materials

About 60 percent of the mapped area consists of tracts of planar surfaces having a variety of small-scale textures. These tracts range in size from a few square kilometers within craters to areas larger than 10,000 km2 that surround and separate large craters: the so-called “intercrater plains”.[3][4] The origin of the plains material is uncertain. Strom and others,[4][5] Trask and Strom,[6] Strom[7] (1977), and Leake (1982) presented arguments in favor of volcanism, whereas Wilhelms[8] and Oberbeck and others (1977) argued for an impact-related origin through processes similar to those responsible for the lunar Cayley Plains (fluidized ejecta sheets or ballistically deposited secondary-crater ejecta). Plains formation occurred throughout the period when visible craters were formed and most likely throughout the period of intense impact cratering[4](Strom, 1977). The time scale for production and retention of plains units is crudely similar to that for the production and retention of craters.

The oldest and most extensive plains material in the Bach region, the intercrater plains material, is characterized by a gently rolling surface and a high density of superposed craters less than 15 km in diameter. Most of these small craters occur in strings or clusters and are irregularly shaped; they appear to be secondaries from craters of c2 through c5 age. Therefore, the intercrater plains unit is thought to be older than most c2 craters. Its relation to c1 craters is not clear. The highly degraded nature of c1 craters makes it impossible to determine whether the craters predate, postdate, or are contemporaneous with the intercrater plains unit. However, the presence of shallow depressions, which may be ancient craters, within this plains material suggests that the unit flooded a preexisting population of craters and therefore was emplaced sometime during the period of late heavy crater bombardment. The two proposed origins for this plains unit, as volcanic or basin-ejecta material, cannot be unambiguously resolved by geologic relations in the Bach region. However, a volcanic origin is favored because of (1) the widespread distribution of the plains material throughout the imaged regions of Mercury, (2) the apparent lack of source basins large enough to supply such great amounts of impact melt, and (3) the restricted ballistic range of ejecta on Mercury.

The intermediate plains material is concentrated mostly in the northeastern part of the Bach region. It is similar in morphology to intercrater plains material but has a lower density of small craters. On the basis of the reasoning applied to the intercrater plains material, the intermediate plains unit is also tentatively ascribed a volcanic origin.

Materials of the smooth plains and very smooth plains are also concentrated mainly in the eastern part of the map area. The smooth plains unit has a lower density of small craters than does intermediate plains material and a somewhat hummocky surface with scattered small hills and knobs. The hummocks within fresh c5 craters may be mantled floor materials or incipient peak rings (see, for example, crater Callicrates at lat 66° S., long 32°; FDS 27402). The very smooth plains unit has virtually no visible small craters and displays smoother planar surfaces than those of the smooth plains unit. It occurs in the lowest areas within smooth plains material (including areas within buried crater depressions) and commonly within older craters. The areas of greatest concentration of smooth and very smooth plains materials also contain the most ridges, which suggests that ridges and the younger plains units are genetically related. Very smooth plains material for instance, commonly lies at the base of ridges or scarps. It occurs as small patches within the smooth plains unit that fills the crater Pushkin. Smooth plains material embays the ejecta blanket of a c3 crater on Pushkin’s rim at lat 66° S, long 28° (FDS 27402) and fills the interior and part of the outer-ring area of Bach. The distribution of these two youngest plains units may indicate that the smooth plains material as mapped is nothing more than a thin, discontinuous layer of very smooth plains material that mantles the older units. In this respect, it is similar to the lunar Cayley Formation, which is probably basin ejecta. However, unlike plains material of the lunar uplands, no source basin is evident for the mercurian smooth and very smooth plains units within the imaged part of the Bach region. Although such a source basin may lie within the part not imaged, intervening areas do not contain smooth or very smooth plains materials. For these reasons we tentatively ascribe a volcanic origin to most of the smooth and very smooth plains material. The ridges appear to be of volcano-tectonic origin; the fracturing may have provided the means by which lavas reached the surface to form these younger plains units. Some very smooth and smooth plains materials that form the floors of c5 and c4 craters may be impact melt.

Structure

The map region displays a wide variety of structural features, including lineaments associated with ridges, scarps, and polygonal crater walls. Joint- controlled mass movements are most likely responsible for the polygonal crater- wall segments; segments as long as 100 km suggest that these fractures extend deep into the lithosphere. The most conspicuous trends of these lineaments are east-west, N.50° W., and N. 40° E. More trends are north-south, N.20° E., and N.70° E.

Large ridges and scarps are the most prominent structural features in the low-sun-angle Mariner 10 pictures of the Bach region. They are most numerous between long 0° and 90°, where they have no preferred orientation.

Ridges may have been formed by several processes, including tectonism and extrusion, or they may be buried crater-rim segments. Several large ridges may represent uplift of plains materials by normal faulting. Other ridges are arcuate to circular, which suggests that they are segments of old, subdued crater and basin rims. Near Boccaccio (centered at lat 81° S., long 30°), ridges are domical in cross section and have smooth tops with small irregular or rimless craters along their crests; they appear to overlap both a c3 and a c1 crater (FDS l66751). In turn, these ridges are superposed by c3 craters and c4 ejecta. The ridges may be volcanotectonic features, composed of extrusives along fissures. However, they are mapped only as ridges because we cannot determine if they are volcanic material that should be mapped as a separate unit or uplifted intercrater plains. These same structures may have been the source of older plains units.

Lobate scarps are the most common structural landforms in the Bach region. Almost all have convex slope profiles, rounded crests, and steep, sharply defined lobes. Three types are seen in the map region: (1) very small (<50 km long, ~100 m high), irregular scarps that commonly enclose topographically depressed areas; they are restricted to the intermediate and smooth plains units in the eastern part of the map region; (2) small (~100 km long, ~100 m high), arcuate or sinuous scarps, also confined primarily to the intermediate and smooth plains units in the eastern part of the map region; and (3) large (>100 km long, ~1 km high), broadly arcuate but locally irregular or sinuous scarps whose faces are somewhat steeper. Several of these scarps (lat 83° S., long 80°) deform craters and offset preexisting features vertically (FDS 166751). The morphology and structural relations of the scarps suggest that most result from thrust or reverse faults. However, an extrusive origin has been suggested by Dzurisin (1978) for a scarp more than 200 km long that extends from about lat 70° S. to the map border between long 45° and 52°; he based this interpretation on albedo differences between the two sides of the scarp and on partial burial of craters transected by it.

Age relations among structural features are not readily apparent. In the Bach region, the youngest craters cut by a scarp are of c4 age; the oldest crater to superpose a scarp is a c3. These relations suggest that scarp formation occurred in c3 to c4 time. Very smooth plains material flanks some scarps and ridges and, if the material is ponded extrusives or mass-wasted products, may postdate the structures. Scarps and ridges are abundant in intercrater, intermediate, and smooth plains units, but they are not embayed by intermediate and intercrater plains materials. These relations suggest that the structures began to form after emplacement of these two oldest plains units. Some of the oldest craters and basins, such as Cervantes, have polygonal shapes at least as marked as more recent craters, suggesting that some structural lineaments are older than c1 craters.

Geologic history

Murray and others (1975) proposed that Mercury’s history could be divided into five periods: (1) accretion and differentiation, (2) “terminal heavy bombardment,” (3) formation of the Caloris basin (centered off map sheet at lat 30° N., long 195° ; U.S. Geological Survey, 1979), (4) filling of the large basins by “smooth plains,” and (5) a period of light impact cratering. Although these divisions have withstood well the assessments of subsequent investigators, they do not define a stratigraphy. Because the geologic map of the Bach region constitutes a synthesis of observation with interpretation, we shall explore several aspects of the region’s geologic development.

The history of the region begins prior to the formation of any presently visible surface, when Mercury’s internal evolution played a key role in determining subsequent landform development. Because it is the planet nearest the Sun, Mercury represents one extreme in possible cosmochemical models of planet formation. Even before the Mariner 10 mission, Mercury’s high density and photometric properties suggested a large core, presumably iron, and a lithosphere of silicate materials. Evidence for an intrinsic dipolar magnetic field (Ness and others, 1974) reinforces interpretations favoring a large core. This core, which formed partly as a result of radiogenic heating, produced additional heating, leading to global expansion and the formation of extensional fractures in the lithosphere (Solomon, 1976, 1977). These fractures may have provided egress for the eruption of the oldest plains material during the period of heavy bombardment. Also about this time other structural lineaments developed, possibly as a result of stresses induced by tidal spin-down from a more rapid rotation rate (Burns, 1976; Melosh, 1977; Melosh and Dzurisin, 1978). The major east-west lineament trend in this polar region (noted in previous section) conforms to a prediction of Melosh (1977) for the orientation of normal faults. However, no unambiguous evidence for tensional faults occurs in the Bach quadrangle.

A population of large, very indistinct, degraded craters, (first noted in stereoscopic images by Malin[4]), occurs within the oldest (intercrater) plains material and is thought by most workers to be coeval with or older than that material. The intercrater unit, presumably volcanic extrusions through tensional fractures, is the most voluminous plains material in the map region. Many large c1 and c2 craters have shallow interiors but moderately well preserved rim features, suggesting that at least some of these craters have undergone topographic adjustment due to isostatic phenomena (Schaber and others, 1977). This adjustment may have been facilitated by a high-temperature mantle that was conducive to “crustal plasticity”[4] (Malin and Dzurisin, 1977). The lesser amount of intermediate plains material indicates decreasing plains formation, some localized within older basins.

Scarps such as Vostok Rupes (in the Discovery quadrangle adjacent to the north) are apparently the expression of thrust faults; they suggest that planetary contraction may have stressed the lithosphere[5] at about the time that c3 craters and smooth plains material were formed. Following core formation, lithospheric cooling and consequent contraction may have closed the conduits, restricting formation of plains material (Solomon, 1977). By c4 time, such formation was greatly reduced.

Theoretical studies by Melosh (1977), based on observations recorded by Dzurisin (1978), suggested that tidal spin-down combined with core or lithospheric contraction could explain many of the tectonic features of Mercury. The scarps occurring in the polar regions do appear to be the result of thrust faulting, which substantiates the suggestion that contraction occurred concurrently with spin-down. Linear structures (other than some ridges) are thus interpreted to form as a result of these two active processes. Fracture and lineament patterns around the Caloris basin[5] suggested to Pechmann and Melosh (1979) that Mercury’s despinning period began before global contraction started and ended during the contraction’s early phases.

Plains formation and cratering continued at reduced rates during the early phases of planetary cooling and contraction. c3 craters are distinguishable by partial retention of secondary craters and by locally prominent morphologic features (McCauley and others, 1981). These characteristics suggest a decreasing rate of resurfacing and of crater modification (Malin and Dzurisin, 1977). The smaller extent of the smooth and very smooth plains units, compared with that of older plains materials, suggests considerable heterogeneity of mercurian crustal materials. Subcrustal zones of tension may have allowed molten materials to reach the surface through fractures beneath craters, even during the period of global contraction (Solomon, 1977). Ridges of domical cross section cut some c4 craters and, at places, flank areas of young, very smooth plains material. Thus, possible volcanic extrusions associated with tectonic activity may have continued into the period of formation of c4 craters and the oldest very smooth plains material.

The period of tectonic adjustment of the mercurian lithosphere lasted at least through the time of formation of smooth plains material; c4 craters that formed during this period are cut by scarps and are superposed on them. Some very smooth plains material, most of which postdates c4 craters, appears to postdate the scarps that it commonly embays. Superposition relations of scarps in other regions of Mercury indicate that tectonic activity may have continued into c5 time (Leake, 1982).

However, the time of formation of c5 craters and very smooth plains material has, for the most part, been tectonically quiescent. During this period, with the exception of a scattering of extremely fresh craters and some minor mass wasting (Malin and Dzurisin, 1977), almost no geologic activity has occurred near the mercurian south pole. The youngest smooth plains and the very smooth plains materials that occur within c5 craters may be impact melts.

| Quadrangles on Mercury | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H-1 Borealis (features) | |||||||

| H-5 Hokusai (features) |

H-4 Raditladi (features) |

H-3 Shakespeare (features) |

H-2 Victoria (features) | ||||

| H-10 Derain (features) |

H-9 Eminescu (features) |

H-8 Tolstoj (features) |

H-7 Beethoven (features) |

H-6 Kuiper (features) | |||

| H-14 Debussy (features) |

H-13 Neruda (features) |

H-12 Michelangelo (features) |

H-11 Discovery (features) | ||||

| H-15 Bach (features) | |||||||

Sources

- Strom, Robert G.; Michael C. Malin; Martha A. Leake (1990). "Geologic Map Of The Bach (H-15) Quadrangle Of Mercury" (PDF). Prepared for the National Aeronautics and Space Administration by the U.S. Department of the Interior, U.S. Geological Survey. (Published in hardcopy as USGS Miscellaneous Investigations Series Map I–2015, as part of the Atlas of Mercury, 1:5,000,000 Geologic Series. Hardcopy is available for sale from U.S. Geological Survey, Information Services, Box 25286, Federal Center, Denver, CO 80225)

References

- ↑ Malin, M.C. (1976). "Comparison of large crater and multiring basin populations on Mars, Mercury and the Moon". Lunar and Planetary Science Conference, 7th, Houston, 1976, Proceedings. 7: 3589–3602. Bibcode:1976LPSC....7.3589M.

- 1 2 Gault, D. E.; Guest, J. E.; Murray, J. B.; Dzurisin, D.; Malin, M. C. (1975). "Some comparisons of impact craters on Mercury and the Moon". Journal of Geophysical Research. 80 (17): 2444–2460. doi:10.1029/jb080i017p02444.

- ↑ Trask, N. J.; Guest, J. E. (1975). "Preliminary geologic terrain map of Mercury". Journal of Geophysical Research. 80 (17): 2461–2477. doi:10.1029/jb080i017p02461.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Malin, M. C. (1976). "Observations of intercrater plains on Mercury". Geophysical Research Letters. 3 (10): 581–584. Bibcode:1976GeoRL...3..581M. doi:10.1029/GL003i010p00581.

- 1 2 3 Strom, R. G.; Trask, N. J.; Guest, J. E. (1975). "Tectonism and volcanism on Mercury". Journal of Geophysical Research. 80 (17): 2478–2507. doi:10.1029/jb080i017p02478.

- ↑ Trask, N. J.; Strom, R. G. (1976). "Additional evidence of mercurian volcanism". Icarus. 28 (4): 559–563. Bibcode:1976Icar...28..559T. doi:10.1016/0019-1035(76)90129-9.

- ↑ Strom, R. G. (1979). "Mercury: A post-Mariner 10 assessment". Space Science Reviews. 24 (1): 3–70. doi:10.1007/bf00221842.

- ↑ Wilhelms, D. E. (1976). "Mercurian volcanism questioned". Icarus. 28 (4): 551–558. doi:10.1016/0019-1035(76)90128-7.

- Burns, J.A., 1976, Consequences of the tidal slowing of Mercury: Icarus, v. 28, no. 4, p 453–458.

- Dzurisin, Daniel, 1978, The tectonic and volcanic history of Mercury as inferred from studies of scarps, ridges, troughs, and other lineaments Journal of Geophysical Research, v. 83, no. B10, p. 4883–4906.

- International Astronomical Union, 1977, Working Group for Planetary System Nomenclature, in 16th General Assembly, Grenoble, 1976, Proceedings: International Astronomical Union Transactions, v. 16B, p. 330–333, 351– 355.

- Leake, M.A., 1982, The intercrater plains of Mercury and the Moon: Their nature, origin, and role in terrestrial planet evolution [Ph. D. dissertation, University of Arizona, Tucson], in Advances in Planetary Geology—1982: National Aeronautics and Space Administration Technical Memorandum 84894, p. 3– 534.

- Malin, M.C., and Dzurisin, Daniel, 1977, Landform degradation on Mercury, the Moon, and Mars: Evidence from crater depth/diameter relationships: Journal of Geophysical Research, v. 82, no. 2, p. 376–388.

- McCauley, J.F., Guest, J.E., Schaber, G.G., Trask, N.J., and Greeley, Ronald, 1981, Stratigraphy of the Caloris Basin, Mercury: Icarus, v. 47, no. 2, p. 184–202.

- Melosh, H.J., 1977, Global tectonics of a despun planet: Icarus, v. 31, no. 2, p. 221–243.

- Melosh, H.J., and Dzurisin, Daniel, 1978, Mercurian global tectonics: A consequence of tidal despinning: Icarus, v. 35, no. 2, p. 227–236.

- Murray, B.C., Strom, R.G., Trask, N.J., and Gault, D.E., 1975, Surface history of Mercury: Implications for terrestrial planets: Journal of Geophysical Research, v. 80, no. 17, p. 2508–2514.

- Ness, N.F., Behannon, K.W., Lepping, R.P., Whang, Y.C., and Schatten, K.H., 1974, Magnetic field observations near Mercury: Preliminary results from Mariner 10: Science, v. 185, no. 4146, p. 151–160.

- Oberbeck, V.R., Quaide, W.L., Arvidson, R.E., and Aggarwal, H.R., 1977, Comparative studies of lunar, martian and mercurian craters and plains: Journal of Geophysical Research, v. 82, p. 1681–1698.

- Pechmann, J.B., and Melosh, H.J., 1979, Global fracture patterns of a despun planet: Application to Mercury: Icarus, v. 38, no. 2, p. 243–250.

- Schaber, G.G., Boyce, J.M., and Trask, N.J., 1977, Moon-Mercury: Large impact structures, isostasy and average crustal viscosity: Physics of the Earth and Planetary Interiors, v. 15, nos. 2–3, p. 189–201.

- Solomon, S.C., 1976, Some aspects of core formation in Mercury: Icarus, v. 28, no. 4, p. 509–521.

- ______1977, The relationship between crustal tectonics and interior evolution in the Moon and Mercury: Physics of the Earth and Planetary Interiors, v. 15, no. 15, p. 135–145.

- Strom, R.G., 1977, Origin and relative age of lunar and mercurian intercrater plains: Physics of the Earth and Planetary Interiors, v. 15, nos. 2–3, p. 156–172.

- Strom, R.G., Murray, B. C., Eggelton, M.J.S., Danielson, G.E., Davies, M.E., Gault, D.E., Hapke, Bruce, O’Leary, Brian, Trask, N.J., Guest, J.E., Anderson, James, and Klassen, Kenneth, 1975, Preliminary imaging results from the second Mercury encounter: Journal of Geophysical Research, v. 80, no. 17, p. 2345–2356.

- U.S. Geological Survey, 1979, Shaded relief map of Mercury: U.S. Geological Survey Miscellaneous Investigations Series Map I-1149, scale 1:15,000,000.