Aymara language

| Aymara | |

|---|---|

| Aymar aru | |

| Native to | Bolivia, Peru and Chile |

| Ethnicity | Aymara people |

Native speakers | 2.8 million (2000–2006)[1] |

|

Aymaran

| |

| Official status | |

Official language in |

Bolivia Peru |

Recognised minority language in | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 |

ay |

| ISO 639-2 |

aym |

| ISO 639-3 |

aym – inclusive codeIndividual codes: ayr – Central Aymara ayc – Southern Aymara |

| Glottolog |

nucl1667[2] |

|

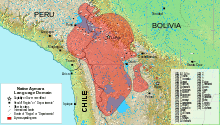

Geographic Distribution of the Aymara language | |

Aymara /aɪməˈrɑː/ (Aymar aru) is an Aymaran language spoken by the Aymara people of the Andes. It is one of only a handful of Native American languages with over one million speakers.[3][4] Aymara, along with Quechua and Spanish, is an official language of Bolivia. It is also spoken around the Lake Titicaca region of southern Peru and, to a much lesser extent, by some communities in northern Chile and in Northwest Argentina.

Some linguists have claimed that Aymara is related to its more widely spoken neighbor, Quechua. That claim, however, is disputed. Although there are indeed similarities, like the nearly-identical phonologies, the majority position among linguists today is that the similarities are better explained as areal features resulting from prolonged interaction between the two languages, and they are not demonstrably related.

Aymara is an agglutinating and, to a certain extent, a polysynthetic language. It has a subject–object–verb word order.

Etymology

The ethnonym "Aymara" may be ultimately derived from the name of some group occupying the southern part of what is now the Quechua speaking area of Apurímac .[5] Regardless, the use of the word "Aymara" as a label for this people was standard practice as early as 1567, as evident from Garci Diez de San Miguel’s report of his inspection of the province of Chucuito (1567, 14; cited in Lafaye 1964). In this document, he uses the term aymaraes to refer to the people. The language was then called Colla. It is believed that Colla was the name of an Aymara nation at the time of conquest, and later was the southernmost region of the Inca empire Collasuyu. However, Cerron-Palomino disputes this claim and asserts that Colla were in fact Puquina speakers who were the rulers of Tiwanaku in the first and third centuries (2008:246). This hypothesis suggests that the linguistically-diverse area ruled by the Puquina came to adopt Aymara languages in their southern region.[6]

In any case, the use of "Aymara" to refer to the language may have first occurred in the works of the lawyer, magistrate and tax collector in Potosí and Cusco, Juan Polo de Ondegardo. This man, who later assisted Viceroy Toledo in creating a system under which the indigenous population would be ruled for the next 200 years, wrote a report in 1559 entitled ‘On the lineage of the Yncas and how they extended their conquests’ in which he discusses land and taxation issues of the Aymara under the Inca empire.

It took over another century for this usage of "Aymara" in reference to the language spoken by the Aymara people to become general use (Briggs, 1976:14). In the meantime the Aymara language was referred to as "the language of the Colla". The best account of the history of Aymara is that of Cerrón-Palomino, who shows that the ethnonym Aymara, which came from the glottonym, is likely derived from the Quechuaized topoynm ayma-ra-y ‘place of communal property’. The entire history of this term is thoroughly outlined in his book, Voces del Ande (2008:19–32) and Lingüística Aimara.[7]

The suggestion that "Aymara" comes from the Aymara words "jaya" (ancient) and "mara" (year, time) is almost certainly a mistaken folk etymology.

Classification

It is often assumed that the Aymara language descends from the language spoken in Tiwanaku on the grounds that it is the native language of that area today. That is very far from certain, however, and most specialists now incline to the idea that Aymara did not expand into the Tiwanaku area until rather recently, as it spread southwards from an original homeland that was more likely to have been in Central Peru.[8] Aymara placenames are found all the way north into central Peru. Indeed, (Altiplano) Aymara is actually the one of the two extant languages of a wider language family, the other surviving representative being Jaqaru.

The family was established by the research of Lucy Briggs (a fluent speaker) and Dr. Martha Hardman de Bautista of the Program in Linguistics at the University of Florida. Jaqaru [jaqi aru = human language] and Kawki communities are in the district of Tupe, Yauyos Valley, in the Dept. of Lima, in central Peru. Terminology for this wider language family is not yet well established. Hardman has proposed the name 'Jaqi' ('human') while other widely respected Peruvian linguists have proposed alternative names for the same language family. Alfredo Torero uses the term 'Aru' ('speech'); Rodolfo Cerrón-Palomino, meanwhile, has proposed that the term 'Aymara' should be used for the whole family, distinguished into two branches, Southern (or Altiplano) Aymara and Central Aymara (Jaqaru and Kawki). Each of these three proposals has its followers in Andean linguistics. In English usage, some linguists use the term Aymaran languages for the family and reserve 'Aymara' for the Altiplano branch.

Dialects

There is some degree of regional variation within Aymara, but all dialects are mutually intelligible.[9]

Most studies of the language focused on either the Aymara spoken on the southern Peruvian shore of Lake Titicaca or the Aymara spoken around La Paz. Lucy Therina Briggs classifies both regions as being part of the Northern Aymara dialect, which encompasses the department of La Paz in Bolivia and the department of Puno in Peru. The Southern Aymara dialect is spoken in the eastern half of the Iquique province in northern Chile and in most of the Bolivian department of Oruro. It is also found in northern Potosí and southwest Cochabamba but is slowly being replaced by Quechua in those regions.

Intermediate Aymara shares dialectical features with both Northern and Southern Aymara and is found in the eastern half of the Tacna and Moquegua departments in southern Peru and in the northeastern tip of Chile.[10]

Geographical distribution

.png)

There are roughly two million Bolivian speakers, half a million Peruvian speakers, and perhaps a few thousand speakers in Chile.[11] At the time of the Spanish conquest in the sixteenth century, Aymara was the dominant language over a much larger area than today, including most of highland Peru south of Cuzco. Over the centuries, Aymara has gradually lost speakers both to Spanish and to Quechua; many Peruvian and Bolivian communities that were once Aymara-speaking now speak Quechua.[12]

Phonology

Vowels

Aymara has three phonemic vowels /a i u/, which, in most varieties of the language, distinguish two degrees of length. Long vowels are indicated with an umlaut in writing: ä ï ü. The high vowels are lowered to mid height when near uvular consonants (/i/ → [e], /u/ → [o]).

Vowel deletion is frequent in Aymara. Every instance of vowel deletion occurs for one of three reasons: (i) phonotactic, (ii) syntactic, and (iii) morphophonemic.[13]

- Phonotactic vowel deletion, hiatus reduction, occurs when two vowels become adjacent as a consequence of word construction or through the process of suffixation. In such environments one of the two vowels deletes: (i) if one of the two vowels is /u/, that vowel will be the only one that surfaces, (ii) if the vowels are /i/ and /a/, the /i/ will surface. (iii) If the sequence is composed of two identical vowels, one will delete.

- Vowel elision can be syntactically conditioned. For example, in nominal compounds and noun phrases, all adjectival/nominal modifiers with three or more vowels in a modifier + nucleus NP lose their final vowel.

- Morphemic vowel deletion is the most common. Some suffixes always suppress the preceding vowel, and some lose their own nucleus under predictable conditions. The class of vowel-suppressing suffixes cannot be defined in terms of some common morphological, morpho-syntactic, or semantic feature. Suffixes from all categories in the language suppress the preceding vowel.

Consonants

As for the consonants, Aymara has phonemic stops at the labial, alveolar, palatal, velar and uvular points of articulation. Stops show no distinction of voice (e.g. there is no phonemic contrast between [p] and [b]), but each stop has three forms: plain (tenuis), glottalized, and aspirated. Aymara also has a trilled /r/, and an alveolar/palatal contrast for nasals and laterals, as well as two semivowels (/w/ and /j/).

| Bilabial | Dental/ Alveolar |

Post- alveolar |

Palatal | Velar | Uvular | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | ɲ | ŋ | |||

| Plosive | voiceless | p | t | t͡ʃ | k | q | |

| aspirated | pʰ | tʰ | t͡ʃʰ | kʰ | qʰ | ||

| ejective | pʼ | tʼ | t͡ʃʼ | kʼ | qʼ | ||

| Fricative | s | x | χ | ||||

| Approximant | central | j | w | ||||

| lateral | l | ʎ | |||||

| Rhotic | ɲ | ||||||

Stress

Stress is usually on the second last syllable, but long vowels may shift it. Also, the final vowel of a word is elided except at the end of a phrase, but the stress remains in the same syllable.

Syllable structure

The vast majority of roots are bisyllabic and, with few exceptions, suffixes are monosyllabic. Roots conform to one of two templates: CV(C)CV or V(C)CV. The former is the most common, with CVCV being predominant. As for the suffixes, the majority are CV, though there are some exceptions: CVCV, CCV, CCVCV and even VCV are possible but rare. The agglutinative nature of this suffixal language, coupled with morphophonological alternations caused by vowel deletion and phonologically conditioned constraints give rise to interesting surface structures that operate in the domain of the morpheme, syllable, and phonological word/phrase. The phonological/morphophonological processes observed include syllabic reduction, epenthesis, deletion, and reduplication.[13]

Orthography

Beginning with Spanish missionary efforts, there have been many attempts to create a writing system for Aymara. The colonial sources employed a variety of writing systems heavily influenced by Spanish, the most widespread one being that of Bertonio. Many of the early grammars employed unique alphabets as well as the one of Middendorf’s Aymara-Sprache (1891).

The first official alphabet to be adopted for Aymara was the Scientific Alphabet. It was approved by the III Congreso Indigenista Interamericano de la Paz in 1954 though its origins can be traced as far back as 1931. Rs. No 1593 (Deza Galindo 1989, 17). It was the first official record of an alphabet, but in 1914, Sisko Chukiwanka Ayulo and Julián Palacios Ríos had recorded what may be the first of many attempts to have one alphabet for both Quechua and Aymara, the Syentifiko Qheshwa-Aymara Alfabeto with 37 graphemes.

Several other attempts followed at various degrees of success to do the same. Some orthographic attempts even expand further: the Alfabeto Funcional Trilingüe, made up of 40 letters (including the voiced stops necessary for Spanish) and created by the Academia de las Lenguas Aymara y Quechua in Puno in 1944 is the one used by the lexicographer Juan Francisco Deza Galindo in his Diccionario Aymara – Castellano / Castellano – Aymara. This alphabet has five vowels ⟨a, e, i, o, u⟩, aspiration is conveyed with an ⟨h⟩ next to the consonant and ejectives with ⟨’⟩. The most unusual characteristic is the expression of the uvular /χ/ with ⟨jh⟩. The other uvular segment, /q/, is expressed by ⟨q⟩, but transcription rules mandate that the following vowel must be ⟨a, e, o⟩ (not ⟨i, u⟩), presumably to account for uvular lowering and to facilitate multilingual orthography.

The alphabet created by the Comisión de Alfabetización y Literatura Aymara (CALA) was officially recognized in Bolivia in 1968 (co-existing with the 1954 Scientific Alphabet). Besides being the alphabet employed by Protestant missionaries, it is also the one used for the translation of the Book of Mormon. It was also in 1968 that de Dios Yapita created his take on the Aymara alphabet at the Instituto de Lenga y Cultura Aymara (ILCA).

Nearly 15 years later, the Servicio Nacional de Alfabetización y Educación Popular (SENALEP) attempted to consolidate these alphabets to create a system which could be used to write both Aymara and Quechua, creating what was known as the Alfabeto Unificado. The alphabet, later sanctioned in Bolivia by Decree 20227 on 9 May 1984 and in Peru as la Resolución Ministeral Peruana 1218ED on 18 November 1985 consists of 3 vowels and 26 consonants and an umlaut to mark vowel length.

In the standard orthography of 1985, the consonants are represented as shown below.

| Bilabial | Dental/ Alveolar |

Post- alveolar |

Palatal | Velar | Uvular | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | ñ | nh | |||

| Plosive | voiceless | p | t | ch | k | q | |

| aspirated | ph | th | chh | kh | qh | ||

| ejective | p’ | t’ | ch’ | k’ | q’ | ||

| Fricative | s | j | x | ||||

| Approximant | central | y | w | ||||

| lateral | l | ll | |||||

| Rhotic | r | ||||||

Morphology

Aymara is a highly agglutinative, suffixal language. All suffixes can be categorized into the nominal, verbal, transpositional and those not subcategorized for lexical category (including stem-external word-level suffixes and phrase-final suffixes),[13] as below:

- Nominal and verbal morphology is characterized by derivational- and inflectional-like suffixes as well as non-productive suffixes.

- Transpositional morphology consists of verbalizers (that operate on the root or phrasal levels) and nominalizers (including an action nominalizer, an agentive, and a resultative).

- Suffixes not subcategorized for lexical category can be divided into three stem-external, word-level suffixes (otherwise known as "independent suffixes") and around a dozen phrase-final suffixes (otherwise known as "sentence suffixes").

Nominal suffixes

- Non-productive nominal suffixes vary considerably by variant but typically include those below. Some varieites additionally also have (1) the suffix -wurasa (< Spanish 'horas'), which expresses ‘when’ on aka ‘this’, uka ‘that’ and kuna ‘what’; (2) temporal suffixes -unt ~ -umt; and (3) -kucha, which attaches to only two roots, jani ‘no’ and jicha ‘now’:

- kinship suffixes, including -la, -lla, -chi, and/or -ta

- the expression of size with -ch’a

- the suffix -sa ‘side’, which attaches to only the demonstratives and kawki ‘where’

- Nominal derivational-like suffixes:

- diminutive suffixes

- delimitative suffix -chapi

- Nominal inflectional-like suffixes:

- Attributive suffix -ni

- Possessive paradigm

- Plural -naka

- Reciprocal/inclusor -pacha

- Case suffixes - Syntactic relations are generally case-marked, with the exception of the unmarked subject. Case is affixed to the last element of a noun phrase, usually corresponding to the head. Most varieties of Aymara have 14 cases (though in many, the genitive and locative have merged into a single form): ablative -ta, accusative (indicated by vowel suppression), allative -ru, benefactive -taki, comparative -jama, genitive -na, instrumental/comitative -mpi, interactive -pura, locative -na, limitative -kama, nominative (zero), perlative -kata, purposive -layku.

Verbal suffixes

All verbs require at least one suffix to be grammatical.

- Verbal derivational-like suffixes

- Direction of motion — Although these suffixes are quite productive, they are not obligatory. The meaning of a word which is affixed with a member of this category is often but not always predictable, and the word formed may have a different meaning than the root.

- Spatial location — The nine spatial locations ones are likewise highly productive and not obligatory. Similarly, the meaning of the word to which a member of this category attaches is typically (but not consistently) predictable. There are also contexts in which the word formed has a meaning that significantly differs from that of the root to which it attaches.

- Valency-increasing — The five valency increasing suffixes may occur on a wide range of verbs but are not obligatory. The meaning expressed when a word receives one of these suffixes is predictable.

- Multipliers/reversers — The two multipliers/reversers are comparatively less productive and are not obligatory. In some contexts, attachment to a verb conveys a reverser meaning and effectively express the opposite of the meaning of the plain root. In this respect, the multipliers/reversers are the most derivational-like of all the suffixes discussed so far.

- Aspect — This category is complicated insofar as it is made up of a diverse array of suffix types, some of which are more productive and/or obligatory than others.

- Others — In some varieties of Aymara, there are three suffixes not classified into the categories above: the verbal comparative -jama, the category buffer -(w)jwa, and the intensifier -paya. Semantically, these three suffixes do not have much in common. They also vary with respect to the degree which they may be classified as more derivational-like or more inflectional-like.

- Verbal inflectional-like suffixes:

- Person/tense — Person and tense are fused into a unitary suffix. These forms are among the most inflectional-like of the verbal suffixes insofar as they are all obligatory and productive. The so-called personal-knowledge tenses include the simple (non-past) and the proximal past. The non-personal knowledge tenses includes the future and distal past.

- Number — The plural verbal suffix, -pha (just as the nominal one,-naka) is optional. Thus, while pluralization is very productive, it is not obligatory.

- Mood and modality — Mood and modality includes mood, evidentials, event modality, and the imperative. These suffixes are both productive and obligatory. Their semantic affect is usually transparent.

Transpositional suffixes

A given word can take several transpositional suffixes:

- Verbalizers: There are six suffixes whose primary function is to verbalize nominal roots (not including the reflexive -si and the propagative -tata). These forms can be subdivided into two groups, (1) phrase verbalizers and (2) root verbalizers.

- Nominalizers: There are three suffixes are used to derive nouns: the agentive -iri, the resultative -ta, and the action nominalizer (sometimes glossed as the "infinitive" in some descriptions) -ña.

Suffixes not subcategorized for lexical categories

There are two kinds of suffixes not subcategorized for lexical categories:

- Stem external word-final suffixes (sometimes known as "independent suffixes") — There are three suffixes that are not classifiable as members of either nominal or verbal morphology and are not phrase-final suffixes: the emphatic -puni, the delimitative -ki, and the additive -raki

- Phrase-final suffixes (sometimes known as "sentence suffixes" in the literature) — Most Aymara phrases have at least one of the eleven (depending on variant) possible phrase-final suffixes to be grammatical. The phrase-final suffix must appear minimally on a noun, noun phrase, verb, or verb phrase (note that two phrase-final suffixes, the additive -sa and the confirmatory -pi appear exclusively on nouns but otherwise pattern with phrase-final suffixes and so may not be best treated with nominal morphology). Exceptions to the requirement that a phrase has at least one phrase-final suffix are mainly limited to imperative constructions.

Idiosyncrasies

Linguistic and gestural analysis by Núñez and Sweetser also asserts that the Aymara have an apparently unique or at least very rare understanding of time, and Aymara is, with Quechua, one of very few [Núñez & Sweetser, 2006, p. 403] languages in which speakers seem to represent the past as in front of them and the future as behind them. Their argument is situated mainly within the framework of conceptual metaphor, which recognizes in general two subtypes of the metaphor "the passage of time is motion:" one is "time passing is motion over a landscape" (or "moving-ego"), and the other is "time passing is a moving object" ("moving-events"). The latter metaphor does not explicitly involve the individual/speaker; events are in a queue, with prior events towards the front of the line. The individual may be facing the queue, or it may be moving from left to right in front of him/her.

The claims regarding Aymara involve the moving-ego metaphor. Most languages conceptualize the ego as moving forward into the future, with ego's back to the past. The English sentences prepare for what lies before us and we are facing a prosperous future exemplify this metaphor. In contrast, Aymara seems to encode the past as in front of individuals and the future behind them; this is typologically a rare phenomenon [Núñez & Sweetser, 2006, p. 416].

The fact that English has words like before and after that are (currently or archaically) polysemous between 'front/earlier' or 'back/later' may seem to refute the claims regarding Aymara uniqueness. However, these words relate events to other events and are part of the moving-events metaphor. In fact, when before means in front of ego, it can mean only future. For instance, our future is laid out before us while our past is behind us. Parallel Aymara examples describe future days as qhipa uru, literally 'back days', and they are sometimes accompanied by gestures to behind the speaker. The same applies to Quechua speakers, whose expression qhipa p'unchaw corresponds directly to Aymara qhipa uru. Possibly, the metaphor is that the past is visible to us (in front of our eyes) while the future is not.

Pedagogy

There is increasing use of Aymara locally and there are increased numbers learning the language, both Bolivian and abroad. In Bolivia and Peru, intercultural bilingual education programs with Aymara and Spanish have been introduced in the last two decades. There are even projects to offer Aymara through the internet, such as by ILCA.[14]

See also

- Jaqaru language

- Indigenous languages of the Americas

- Languages of Peru

- List of Spanish words of Indigenous American Indian origin

Footnotes

- ↑ Aymara at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015)

Central Aymara at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015)

Southern Aymara at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) - ↑ Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin; Bank, Sebastian, eds. (2016). "Nuclear Aymara". Glottolog 2.7. Jena: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- ↑ "Bolivia: Idioma Materno de la Población de 4 años de edad y más- UBICACIÓN, ÁREA GEOGRÁFICA, SEXO Y EDAD". 2001 Bolivian Census. Instituto Nacional de Estadística, La Paz — Bolivia.

- ↑ The other native American languages with more than one million speakers are Nahuatl, Quechua languages, and Guaraní.

- ↑ Willem Adelaar with Pieter Muysken, Languages of the Andes, CUP, Cambridge, 2004, pp 259

- ↑ Coler, Matt (2015). A Grammar of Muylaq' Aymara: Aymara as spoken in Southern Peru. Brill's Studies in the Indigenous Languages of the Americas. Brill. p. 9. ISBN 978-9-00-428380-0.

- ↑ Rodolfo Cerron-Palomino, Lingüística Aimara, Centro de Estudios Regionales Andinos "Bartolomé de las Casas", Lima, 2000, pp 34-6.

- ↑ Heggarty, P.; Beresford-Jones, D. (2013). "Andes: linguistic history.". In Ness, I.; P., Bellwood. The Encyclopedia of Global Human Migration. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 401–409.

- ↑ SIL's Ethnologue.com and the ISO designate a Southern Aymara dialect found in between Lake Titicaca and the Pacific Coast in southern Peru and a Central Aymara dialect found in western Bolivia and northeastern Chile. Such classifications, however, are not based upon academic research and are probably a misinterpretation of Cerron-Palomino's classification of the language family.

- ↑ Lucy Therina Briggs, Dialectal Variation in the Aymara Language of Bolivia and Peru, Dissertation, University of Florida, Gainesville, 1976; Adalberto Salas and María Teresa Poblete, "El aimara de Chile (fonología, textos, léxico)", Revista de Filología y Lingüística de la Universidad de Costa Rica, Vol XXIII: 1, pp 121-203, 2, pp 95-138; Cerron-Palomino, 2000, pp 65-8, 373.

- ↑ Ethnologue: 1.785 million in Bolivia in 1987; 442 thousand of the central dialect in Peru in 2000, plus an unknown number of speakers of the southern dialect in Peru; 900 in Chile in 1994 out of a much larger ethnic population.

- ↑ Xavier Albó, "Andean People in the Twentieth Century," in The Cambridge History of the Native Peoples of the Americas. Vol. III: South America, ed. Frank Salomon and Stuart B. Schwartz (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1999), 765-871.

- 1 2 3 Matt Coler, A Grammar of Muylaq' Aymara: Aymara as spoken in Southern Peru. Brill: Leiden, 2014.

- ↑ http://www.ilcanet.org/ciberaymara

References

- Coler, Matt. A Grammar of Muylaq' Aymara: Aymara as spoken in Southern Peru. Brill: Leiden, 2014.

- Núñez, R., & Sweetser, E. With the Future Behind Them : Convergent Evidence From Aymara Language and Gesture in the Crosslinguistic Comparison of Spatial Construals of Time. Cognitive Science, 30(3), 401-450.

Further reading

- Coler, Matt. A Grammar of Muylaq' Aymara: Aymara as spoken in Southern Peru. Brill: Leiden, 2014. ISBN 9789004283800

- Coler, Matt. The grammatical expression of dialogicity in Muylaq’ Aymara narratives. International Journal of American Linguistics, 80(2):241–265. 2014.

- Coler, Matt and Edwin Banegas Flores. A descriptive analysis of Castellano Loanwords in Muylaq' Aymara. LIAMES – Línguas Indígenas Americanas 13:101-113.

- Gifford, Douglas. Time Metaphors in Aymara and Quechua. St. Andrews: University of St. Andrews, 1986.

- Guzmán de Rojas, Iván. Logical and Linguistic Problems of Social Communication with the Aymara People. Manuscript report / International Development Research Centre, 66e. [Ottawa]: International Development Research Centre, 1985.

- Hardman, Martha James. The Aymara Language in Its Social and Cultural Context: A Collection Essays on Aspects of Aymara Language and Culture. Gainesville: University Presses of Florida, 1981. ISBN 0-8130-0695-3

- Hardman, Martha James, Juana Vásquez, and Juan de Dios Yapita. Aymara Grammatical Sketch: To Be Used with Aymar Ar Yatiqañataki. Gainesville, Fla: Aymara Language Materials Project, Dept. of Anthropology, University of Florida, 1971.

- Hardman, Martha James. Primary research materials online as full-text in the University of Florida's Digital Collections, on Dr. Hardman's website, and learning Aymara resources by Dr. Hardman.

External links

| Aymara edition of Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia |

- Aymara on The Internet A course for Aymara available in English and Spanish.

- Aymara Swadesh vocabulary lists (from Wiktionary's Swadesh-list appendix)

- http://clas.uchicago.edu/language_teaching/aymara.shtml

- www.aymara.org An extensive website about the language in English, Spanish and Aymara.

- The Sounds of the Andean Languages listen online to pronunciations of Aymara words, see photos of speakers and their home regions, learn about the origins and varieties of Aymara.

- Bolivians equip ancient language for digital times

- Encyclopedy in Aymara

- Aymara – English Dictionary: from Webster's Online Dictionary – The Rosetta Edition.

- Andean language looks back to the future – article on Aymara's reversed concept of time, with the past ahead and the future behind

- JACH'AK'ACHI. Patpatankiri markana kont’awipa An aymara page dedicated to this city in aymara language.

- Beginning Aymara – a course book in pdf form

- Vocabulario de la Lengua Aymara, a historical dictionary by Ludovico Bertonio (1612).

- Yatiqirinaka Aru Pirwa, Qullawa Aymara Aru, a children's Aymara dictionary by the Peruvian Ministry of Education (2005).

- AruSimiÑee, Aymara pedagogical vocabulary by the Bolivian Ministry of Education (2004).

Spanish

- Aymara – Compendio de Estrutura Fonológica y Gramatical, 20 downloadable PDF files