Australia–New Zealand relations

|

|

Australia |

New Zealand |

|---|---|

Australia–New Zealand relations, also referred to as Trans-Tasman relations ("relations across the Tasman Sea"), are extremely close with both sharing British colonial heritage as Antipodean White Dominions and settler colonies as well as being part of the wider Anglosphere.[1] New Zealand sent representatives to the constitutional conventions which led to the uniting of the six Australian colonies but opted not to join; still, in the Boer War and in World War I and World War II, soldiers from New Zealand fought alongside Australians. In recent years the Closer Economic Relations free trade agreement and its predecessors have inspired everconverging economic integration. The culture of Australia does differ from the culture of New Zealand and there are sometimes differences of opinion which some have declared as symptomatic of sibling rivalry.[2] This often centres upon sports such as rugby union or cricket[3] or in commercial tensions such as those arising from the failure of Ansett Australia or those engendered by the formerly[4] long-standing Australian ban on New Zealand apple imports.

Both countries are Commonwealth realms sharing the Head of the Commonwealth as Head of State in universal suffrage supported systems of Westminster representative parliamentary democracy within a constitutional monarchy. Their only land border defines the western extent of the Ross Dependency and eastern extent of the Australian Antarctic Territory. They acknowledge two distinct maritime boundaries conclusively delimited by the Australia – New Zealand Maritime Treaty of 2004.

History

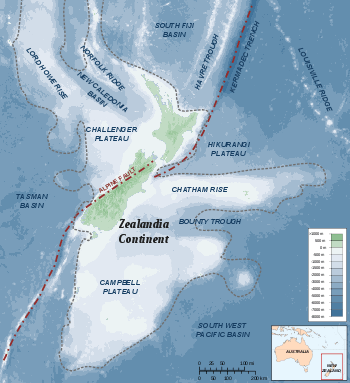

The microcontinent Zealandia, of which present day New Zealand represents the largest unsubmerged part, probably separated from Antarctica between 130 and 85 million years ago and then from the separate continent of Australia 60–85 million years ago[6] in the break-up of East Gondwana occurring in the Cretaceous and early Paleogene geologic periods. Zealandia and Australia together are part of the wider regions known as Oceania and Australasia. Australia, New Zealand's North Island and the northwest of the South Island are on the Indo-Australian Plate, with the remainder of the South Island on the Pacific Plate.

The History of Indigenous Australians on their own continent is generally thought to be rich to the extent of at least 40,000–45,000 years duration, whereas Polynesian Māori arrived in Aotearoa/New Zealand in several waves by means of waka some time before 1300.[7] Australoid indigenous Australians and Polynesian Māori indigenous to New Zealand are not recorded to have met or interacted prior to 17th and 18th century European exploration of Australia. Regarding the respective indigenous populations, while it may be said that there is a single Māori language and the iwi have been able to present as a unified population represented by a monarch neither has ever been able to be said of the Australian aboriginal languages or their corresponding population groups.[8]

The first European landing on the Australian continent occurred in the Janszoon voyage of 1605–06. Abel Tasman in two distinct voyages in the period 1642–1644 is recorded as the first person to have coastally explored regions of the respective landforms including Van Diemen's Land – later named for him as the Australian state of Tasmania. The first voyage of James Cook stands as significant for the circumnavigation of New Zealand in 1769 and as the European discovery and first ever coastal navigation of Eastern Australia from April to August 1770. The European settlement of Australia and New Zealand, then referred to as the colony of New South Wales, dates from the arrival of the First Fleet into Cadi/Port Jackson on Australia Day, 1788.

New Zealand was separated from the Colony of New South Wales in 1840, at which time its pākehā population number about 2000 descended from Christian missionaries, sealers, and whalers (as opposed to mainland Australia's much larger penal colony population).[9]

Although it is accurate to distinguish that New Zealand was never a penal colony, neither were some of the Australian colonies. In particular, South Australia was founded and settled in a similar manner to New Zealand, both being influenced by the ideas of Edward Gibbon Wakefield.[10]

Both countries experienced ongoing internal conflict concerning indigenous and settler populations, although this conflict took very different forms most sharply manifested in the New Zealand land wars and Australian frontier wars respectively. Whereas Maori iwi endured the Musket Wars of the period 1807–1839 preceding the former in New Zealand, indigenous Australians have no comparable period of the experience of warfare amongst each other employing European-introduced modern weaponry either before or after their own confrontations with European settler society.[8] Both countries experienced nineteenth century gold rushes and during the nineteenth century there was extensive trade and travel between the colonies.[11]

New Zealand participated as a member of the Federal Council of Australasia from 1885 and fully involved itself among the other selfgoverning colonies in the 1890 conference and 1891 Convention leading up to Federation of Australia. Ultimately it declined to accept the invitation to join the Commonwealth of Australia resultingly formed in 1901, remaining as a self-governing colony until becoming the Dominion of New Zealand in 1907 and with other territories later constituting the Realm of New Zealand effectively as an independent country of its own. In the 1908 Olympics, the 1911 Festival of Empire and the 1912 Olympics the two countries were represented at least in sporting competition as the unified entity "Australasia".

Both continued to co-operate politically in the 20th century as each sought closer relations with the United Kingdom, particularly in the area of trade. This was helped by the development of refrigerated shipping, which allowed New Zealand in particular to base its economy on the export of meat and dairy – both of which Australia had in abundance – to Britain.

The two nations sealed the Canberra Pact in January 1944 for the purpose of successfully prosecuting war against the Axis Powers in World War II and providing for the administration of an armistice and territorial trusteeship in its aftermath. The Agreement foreshadowed the establishment of a permanent Australia–New Zealand Secretariat, it provided for consultation in matters of common interest, it provided for the maintenance of separate military commands and for "the maximum degree of unity in the presentation ... of the views of the two countries".[12]

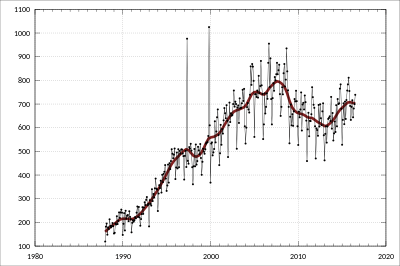

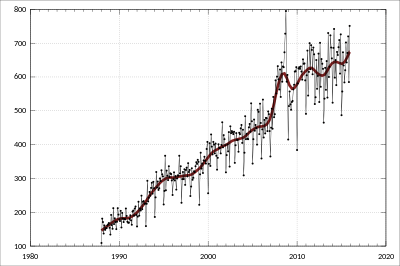

The quantity of trans-Tasman trade increased by 9% per annum from the early 1980s through to the end of 2007,[13] with the Closer Economic Relations free trade agreement of 1983 being a major turning point. This was partially a result of Britain joining the European Economic Community in the early 1970s, thus restricting the access of both countries to their biggest export market.

Military

In the Harriet Affair of 1834, a group of British soldiers of the 50th Regiment from Australia landed in Taranaki, New Zealand, to rescue the wife and children of John (Jacky) Guard and punish the kidnappers – the first clash between Māori and British troops. The expedition was sent by Governor Bourke from Sydney and was subsequently criticised for use of excessive force by a British House of Commons report in 1835.[14][15]

In 1861, the Australian ship HMCSS Victoria was dispatched to help the New Zealand colonial government in its war against Māori in Taranaki. Victoria was subsequently used for patrol duties and logistic support, although a number of personnel were involved in actions against Māori fortifications.[16] In late 1863, the New Zealand government requested troops to assist in the invasion of the Waikato. Promised settlement on confiscated land, more than 2500 Australians were recruited. Other Australians became scouts in the Company of Forest Rangers. Australians were involved in actions at Matarikoriko, Pukekohe East, Titi Hill, Ōrākau and Te Ranga.[16][17]

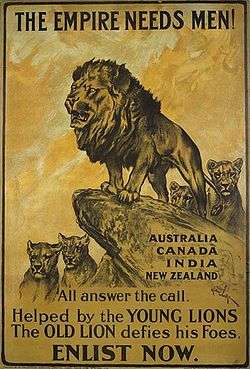

In the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries, both countries or their colonial precursors were enthusiastic members of the British Empire and both either sent soldiers or permitted the sending of military volunteers to the Mahdist War in the Sudan, the quelling of the Boxer Rebellion, the Second Boer War, the First and Second World Wars and the Malayan Emergency and Konfrontasi. Independent of the sense of Empire (or Commonwealth), both nations in the second half of the twentieth century otherwise provided contingents in support of United States strategic aims in the Korean War, Vietnam War, and Gulf War. Whereas military personnel from both countries participated in UNTSO, the Multinational Force and Observers to Sinai, INTERFET to East Timor, the Regional Assistance Mission to Solomon Islands, UNMIS to Sudan, and more recent intervention in Tonga the New Zealand government officially condemned the 2003 invasion of Iraq and stood apart from Australia in refusing to contribute any combat forces. Somewhat similarly in 1982, although without speaking in condemnation, Australia found no purpose in joining with New Zealand to support the United Kingdom in the Falklands War against Argentina[8] just as New Zealand had declined to join Australia in Allied intervention in the Russian Civil War or in UNEF to Egypt and Israel during the 1970s.

In the First World War, the soldiers of both countries were formed into the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps (ANZACs). Together Australia and New Zealand saw their first major military action in the Battle of Gallipoli, in which both suffered major casualties. For many decades the battle was seen by both countries as the moment at which they came of age as nations.[18][19] It continues to be commemorated annually in both countries on Anzac Day, although since the 1960s there has been some questioning of the "coming of age" idea.

World War II was a major turning point for both countries, as they realised that they could no longer rely on the protection of Britain.[20] Australia was particularly struck by this realisation, as it was directly targeted by the Empire of Japan, with Darwin bombed and Broome attacked. Subsequently, both countries sought closer ties with the United States. This resulted in the ANZUS pact of 1951, in which Australia, New Zealand and the United States agreed to defend each other in the event of enemy attack. Although no such attack occurred until, arguably, 11 September 2001, Australia and New Zealand both contributed troops to the Korean and Vietnam Wars. Australia's contribution to the Vietnam War in particular was much larger than New Zealand's; while Australia introduced conscription,[21] New Zealand sent only a token force.[22] Australia has continued to be more committed to the American alliance, ANZUS, than New Zealand; although both countries felt considerable unease about American military policy in the 1980s, New Zealand angered the United States by refusing port access to nuclear ships into its nuclear-free zone from 1985 and in retaliation, the United States 'suspended' its obligations otherwise owed under the alliance treaty to New Zealand.[23] Australia has made a significant contribution to the Iraq War, while New Zealand's much smaller military contribution was limited to UN-authorised reconstruction tasks.[24]

Anzac Bridge in Sydney was given its current name on Remembrance Day in 1998 to honour the memory of the ANZAC serving in World War I. An Australian flag flies atop the eastern pylon and a New Zealand flag flies atop the western pylon. A bronze memorial statue of a digger holding a Lee–Enfield rifle pointing down was placed on the western end of the bridge on Anzac Day in 2000. A statue of a New Zealand soldier was added to a plinth across the road from the Australian Digger, facing towards the east, and unveiled by Prime Minister of New Zealand Helen Clark in the presence of Premier of New South Wales Morris Iemma on Sunday 27 April 2008.[25]

In 2001 the Australia–New Zealand Memorial was opened by the prime ministers of both countries on Anzac Parade, Canberra. The memorial commemorates the shared effort to achieve common goals in both peace and war.[26]

Joint defence arrangements involving both countries include the Five Power Defence Arrangements, ANZUS, and the UK-USA Security Agreement for intelligence sharing. Since 1964, Australia, and since 2006, New Zealand have been parties to the ABCA interoperability arrangement of national defence forces. ANZUK was a tripartite force formed by Australia, New Zealand and the United Kingdom to defend the Asian Pacific region after the United Kingdom withdrew forces from the east of Suez in the early seventies. The ANZUK force was formed in 1971 and disbanded in 1974. The SEATO anti-communist defence organisation also extended membership to both countries for the duration of its existence from 1955 to 1977.

Exploration

The Australasian Antarctic Expedition 1911–1914 established radio connection back to Tasmania via Macquarie Island, surveyed King George V Land and examined the rock formations of Wilkes Land. Mawson's Huts at Cape Denison survive to the current day as habitations at the expedition's chosen base. The expedition's Western Base Party made a number of discoveries and explored into Kaiser Wilhelm II Land from initial stationing in Queen Mary Land. The territorially acquisitive BANZARE expedition of 1929–1931, additionally collaborating with the UK, mapped the coastline of Antarctica and discovered Mac Robertson Land and Princess Elizabeth Land. Both expeditions reported voluminously.[27][28]

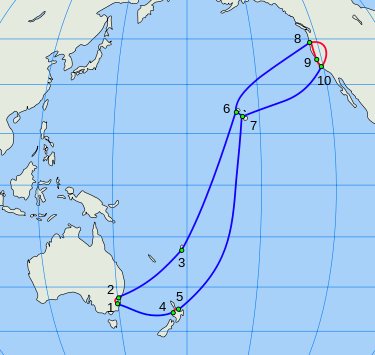

Aerial crossing of the Tasman was first achieved by Charles Kingsford Smith with Charles Ulm and crew travelling by return journey in 1928, improving upon failure by Moncrieff and Hood deceased earlier the same year. Guy Menzies then completed solo crossing in 1931. Rowing crossing was first successfully completed, solo, by Colin Quincey in 1977[29] and then by teams of kayakers in 2007.[30] A pioneering solo kayak journey from Tasmania by Andrew McAuley in early 2007 ended with his disappearance at sea and presumed death in New Zealand waters 30 nmi short of landfall at Milford Sound.[31]

Telecommunications

The first international cable landing on New Zealand soil was that laid in 1876 from La Perouse, New South Wales to Wakapuaka, New Zealand. The major part of that cable was renewed in 1895 and it was withdrawn from service in 1932. A second trans-Tasman submarine cable was laid in 1890 between Sydney and Wellington, New Zealand and then in 1901 the Pacific cable from Norfolk Island was landed in Doubtless Bay, North Island. In 1912 a 2,270 km (1,225 nmi) cable was laid from Sydney to Auckland.[32]

The two countries additionally established communication via undersea laid coaxial cable in July 1962,[33] and the NZPO-OTC joint venture TASMAN cable laid in 1975.[32] These were retired by effect of the laying of analogue signal submarine cable linking Australia's Bondi Beach to Takapuna, New Zealand via Norfolk Island in 1983,[34] which itself in turn was supplemented and eventually outmoded by optical fibre cable laid between Paddington, New South Wales and Whenuapai, Auckland in 1995.[35]

The trans-Tasman leg of the high capacity fibre-optic Southern Cross Cable has been operational from Alexandria, New South Wales to Whenuapai since 2001. Another high capacity direct linkage is proposed for construction to be operational in 2013,[36] and yet another for early 2014.[37]

Migration

There are many people who have emigrated from New Zealand to Australia, including former Premier of South Australia, Mike Rann, comedian turned psychologist Pamela Stephenson and actor Russell Crowe. Australians who have emigrated to New Zealand include the 17th and 23rd Prime Ministers of New Zealand Sir Joseph Ward and Michael Joseph Savage, Russel Norman, former co-leader of the Green Party, and Matt Robson, former deputy leader of the Progressive Party.[38]

Under various arrangements since the 1920s, there has been a free flow of people between Australia and New Zealand.[39] Since 1973 the informal Trans-Tasman Travel Arrangement has allowed for the free movement of citizens of one nation to the other. The only major exception to these travel privileges is for individuals with outstanding warrants or criminal backgrounds who are deemed dangerous or undesirable for the migrant nation and its citizens. New Zealand passport holders are issued with special category visas on arrival in Australia, while Australian passport holders are issued with residence class visas on arrival in New Zealand.

In recent decades, many New Zealanders have migrated to Australian cities such as Sydney, Brisbane, Melbourne and Perth.[40] Many such New Zealanders are Maori Australians. Although this agreement is reciprocal there has been resulting significant net migration from New Zealand to Australia.[41] In 2001 there were eight times more New Zealanders living in Australia than Australians living in New Zealand,[42] and in 2006 it was estimated that Australia's real income per person was 32 percent higher than that of New Zealand and its territories.[43] Comparative surveys of median household incomes also confirm that those incomes are lower in New Zealand than in most of the Australian States and Territories. Visits in each direction exceeded one million in 2009, and there are around half a million New Zealand citizens in Australia and about 65,000 Australians in New Zealand.[44] There have been complaints in New Zealand that there is a clearly manifested brain drain to Australia.[45]

New Zealanders in Australia previously had immediate access to Australian welfare benefits and were sometimes characterised as bludgers. In 2001 this was described by New Zealand Prime Minister Helen Clark as a "modern myth". Regulations changed in 2001 whereby New Zealanders must wait two years before being eligible for such payments.[46] All New Zealanders who have moved to Australia after February 2001 are placed on a Special Category Visa, classing them as temporary residents, regardless of how long they reside in Australia. This visa is also passed on to their children. As temporary residents, they are ineligible for government support, aid, emergency programmes, welfare, public housing and disability support in Australia. Attempts by the Queensland Government to pass a law that would allow government agencies to deny support based on residency status without it being considered discriminatory were condemned by Queensland's anti-discrimination commission as an attempt to legalise state discrimination against New Zealanders, claiming it would create a "permanent second class of people".[47] Australians entering New Zealand are deemed "residents" and are not immediately entitled to social security and tax benefits until they have resided in New Zealand for two years. Children born to Australians in New Zealand are granted New Zealand citizenship by birth as well as Australian citizenship by descent.

New Zealand Ministry of Education figures show the number of Australians at New Zealand tertiary institutions almost doubled from 1,978 students in 1999 to 3,916 in 2003. In 2004 more than 2700 Australians received student loans and 1220 a student allowance. Unlike other overseas students, Australians pay the same fees for higher education as New Zealanders, and are eligible for student loans and allowances once they have lived in New Zealand for two years. New Zealand students are not treated on the same basis as Australian students in Australia.[48]

Persons born in New Zealand continue to be the second largest source of immigration to Australia, representing 11% of total permanent additions in 2005–06 and accounting for 2.3% of Australia's population in June 2006.[49] At 30 June 2010, an estimated 566,815 New Zealand citizens were present in Australia.[39]

Trade

New Zealand's economic ties with Australia are strong, especially since the demise of Britain as a trading partner following the latter's decision to join the European Economic Community in 1973. Effective from 1 January 1983 the two countries concluded the Australia New Zealand Closer Economic Relations Trade Agreement (ANZCERTA) for the purpose of allowing each country access to the other's markets. Two-way trade between Australia and New Zealand was A$20.6 billion (NZ$25 billion) in 2009, including goods and services, only slightly lower than the previous year despite the economic downturn.[44] The total accumulated bilateral investment stands at over A$90 billion (NZ$110 billion).[44]

Flowing from the implementation of the ANZCERTA:[50]

- by agreement from 1988 there will be consultation between the respective governments as part of any variation to industry assistance measures and work towards harmonisation of common administrative procedures for quarantine

- additional services were brought within the Agreement's scope from January 1989

- remaining tariffs and quantitative restrictions in bilateral trade were eliminated prior to 1 July 1990

- from 1991 under the Joint Accreditation System of Australia and New Zealand, JAS-ANZ has existed as the joint authority for the accreditation of conformity assessment bodies in the fields of certification and inspection; also, a Government Procurement Agreement was reached[51] and legislation to establish Food Standards Australia New Zealand was promulgated that year.[52]

- a double taxation agreement was sealed in 1995

- co-operation to harmonise customs policies and procedures has existed since 1996

- agreement on food inspection measures was reached in 1996

- from 1998 goods that may legally be sold in either country may be sold in the other and a person who is registered to practise an occupation in either country is entitled to practise an equivalent occupation in the other. A Reciprocal Health Care Agreement was reached in the same year.

- the Consultative Group on Biosecurity Cooperation was established in 1999 to function as a high-level Trans-Tasman dialogue convening and reporting annually[53]

- an "Open Skies Agreement" effective from November 2000 committed to the enjoyment of all freedoms of the air by airlines operating out of places in either country and the existence of an Australia–New Zealand aviation and air safety common market

- an MOU on business law co-ordination was reached in 2000

- a social security agreement was reached in 2001

- a joint food standards code issued in 2002

- from October 2002 the Pacific Agreement on Closer Economic Relations (PACER) inclusive of the two countries plus the Forum Island Countries has taken effect

- trans-Tasman imputation reform occurred in 2003

- revised rules of origin took effect in 2007 with a review by the end of 2009 and a transitional implementation period extending to the end of 2011[54]

- a revised Australia New Zealand Government Procurement Agreement entered into force in 2008[55]

- the Joint Statement of Intent: Single Economic Market Outcome Framework issued in August 2009[56] and has been subsequently worked upon[44]

- the Agreement Establishing the ASEAN Australia New Zealand Free Trade Area came into force on 1 January 2010[44]

Artist's impression of SKA central core

Artist's impression of SKA central core - a business-initiated and AUSTRADE/InvestmentNZ-sponsored first joint Australia–New Zealand Investment Conference was held in Auckland in March 2010[44]

- the Joint Food Standards Treaty came into force in June 2010[44]

- a revised MOU on Coordination of Business Law was signed in 2010[44]

- a commitment for the two countries to jointly bid for hosting the Square Kilometre Array of exploratory radio telescopes has been resolved and telescopes in the two countries have already successfully been linked for VLBI experimentation[44]

- CER Ministerial Forums have been held annually with an occurrence as recent as June 2010 at which investigation into trans-Tasman mobile roaming arrangements was identified as an issue of priority concern[44] along with co-operation for the international enforcement of understandings and controls on logging, emissions and other environmental matters

- from 30 June 2010, commencing with The Hon. Tim Groser, New Zealand's Minister for Trade is invited to membership of what was formerly Australia's Ministerial Council on International Trade[44]

One example of a formerly longstanding trading issue unresolved by the closer economic relations was Australia's restriction of the import of apples from New Zealand owing to fear of introducing fire blight disease. A ban on importation of New Zealand apples into Australia had been in place since 1921, following the discovery of fire blight in New Zealand in 1919. New Zealand authorities applied for re-admittance to the Australian market in 1986, 1989 and 1995, but the ban continued.[57] Further talks over Australia's import restrictions on apples from New Zealand failed, and New Zealand initiated WTO dispute resolution proceedings in 2007.[58][59] Only in 2010 did the WTO order Australia, over its sustained appeals and objections, to vary those import restrictions.[4]

The Australia New Zealand Leadership Forum is a business-led initiative designed to further develop Australia and New Zealand's bilateral relationship as well as their joint relations in the region. The ninth and most recent such convened on 9 April 2011.[60][61]

Monetary

Political conditions in the aftermath of the Battle of Waterloo in 1815 smoothed informal adoption of the British Pound Sterling in New South Wales with relative ease, such adoption proceeding to expand out to New Zealand and other regions of Oceania in time. Having adopted a successful Gold Specie Standard in 1821, the British Government decided in 1825 to introduce the sterling coinage to all of its colonies as a matter of policy. From the latter half of the 19th century until the outbreak of World War I, a monetary union, based on the British gold sovereign existed in a part of the British Empire which included all of both countries and their dependencies.

In 1910, Australia introduced its own currency in the likeness of sterling currency. The Great Depression was the catalyst that forced more dramatic shifts in the exchange rates between the various pound units, and hence the introduction of the New Zealand pound in 1933. Both national currencies had membership of the sterling area from 1939 until its effective demise in 1972. Both adjusted their peg to be the US dollar in 1971, with first Australia and then New Zealand having fortuitously already decimalised their monetary units on 14 February 1966 and 10 July 1967 respectively, both replacing the pound with the dollar at a rate of £1 to $2. The Australian dollar was floated in December 1983, as subsequently also was the New Zealand dollar in March 1985.

Contemporary dollarisation by either country to the currency of the other or the more involved currency union entailing amalgamation of the central banks and economic regulatory systems of both countries have been proposed and discussed though in no way implemented.[62]

Law

Both nations adhere to secular common law legal systems acknowledging the rule of law; and the separation of powers. Like the United States and Canada, however, Australia is a federal nation with a written constitution. New Zealand, like the United Kingdom, is a unitary state with parliamentary sovereignty. Australia lacks a treaty with its indigenous peoples, whereas New Zealand has had the Treaty of Waitangi from 1840 albeit subsequently breached and disregarded for much of its existence. In acknowledgement of indigenous land rights including aboriginal title, the National Native Title Tribunal and Waitangi Tribunal in the respective nations take similar jurisdiction and powers.

Both judicial systems are now independent of the ultimate authority of the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council. Whereas the Constitution of New Zealand is not one that is either codified or entrenched, the Constitution of Australia has had the Commonwealth of Australia Constitution Act as such an entrenched codification embodying a written constitution.

New Zealand contract law is now largely distinct from that of Australia due the effect of Acts of the New Zealand Parliament promulgated since 1969.[63] Main among them is the wide discretionary power given to New Zealand courts in granting relief.

In 2005 and 2006 the Australian House of Representatives Standing Committee on Legal and Constitutional Affairs enquired into the harmonisation of legal systems within Australia, and with New Zealand, with particular reference to those differences that affect trade and commerce.[64] The Committee stated that the already close relationship between Australia and New Zealand should be closer still and that:

| “ | In this era of globalisation, it makes sense for Australia and New Zealand to look at moving closer together and further aligning their regulatory frameworks. | ” |

Key recommendations on the Australia–New Zealand relationship included:

- Establishment of a trans-Tasman parliamentary committee to monitor legal harmonisation and examine options including closer association or union;

- Pursuit of a common currency;

- Offering New Zealand Ministers full membership of Australian ministerial councils;

- Work to advance harmonisation of the two banking and telecommunications regulation frameworks.[65]

New Zealand as an Australian state

The 1901 Australian Constitution included provisions to allow New Zealand to join Australia as its seventh state, even after the government of New Zealand had already decided against such a move.[66] The sixth of the initial defining and covering clauses in part provides that:

'The States' shall mean such of the colonies of New South Wales, New Zealand, Queensland, Tasmania, Victoria, Western Australia, and South Australia, including the northern territory of South Australia, as for the time being are parts of the Commonwealth, and such colonies or territories as may be admitted into or established by the Commonwealth as States; and each of such parts of the Commonwealth shall be called 'a State'.

One of the reasons that New Zealand chose not to join Australia was due to perceptions that the indigenous Māori population would suffer as a result.[67] At the time of Federation, indigenous Australians were only allowed to vote if they had been previously allowed to in their state of residence, unlike the Māori in New Zealand, who had equal voting rights from the founding of the colony. Moreover, and most ironically Māori people had voting rights in Australia in certain jurisdictions between 1902 and 1962 as a result of the Commonwealth Franchise Act 1902, part of the effort to allay New Zealand's concerns about joining the Federation.[68] All Indigenous Australians did not have universal suffrage until 1962. During the parliamentary debates over the Act, King O'Malley supported the inclusion of Māori, and the exclusion of Australian Aboriginals, in the franchise, arguing that:

| “ | An aboriginal is not as intelligent as a Maori. There is no scientific evidence that he is a human being at all.[69] | ” |

From time to time the idea of joining Australia has been mooted, but has been ridiculed by some New Zealanders. When Australia's former opposition leader, John Hewson, raised the issue in 2000, New Zealand's Prime Minister Helen Clark remarked that he could "dream on".[70] A 2001 book by Australian academic Bob Catley, then at the University of Otago, titled Waltzing with Matilda: should New Zealand join Australia?, was described by New Zealand political commentator Colin James as "a book for Australians".[71]

Unlike Canadians and Americans, who share a mainland land border, Australia and New Zealand are more than 1,491 km apart. Arguing against Australian statehood, New Zealand's Premier, Sir John Hall, remarked that there were "1,200 reasons" not to join the federation.[72]

Both countries have contributed to the sporadic discussion on a Pacific Union, although that proposal would include a much wider range of member-states than just Australia and New Zealand.

A result of the rejected 1999 Australian republican referendum was that Australians retained a common head of state with New Zealand. Whereas none of the major political parties in New Zealand have a policy of encouraging republicanism, the Australian Labor Party has long favoured a republic, as have some politicians in the Liberal Party, although National Prime Minister Jim Bolger spoke in favour of a republic in 1994.[73]

While there is little prospect of political union now, in 2006 there was a recommendation from an Australian federal parliamentary committee that a full union should occur or Australia and New Zealand should at least have a single currency and more common markets.[74] New Zealand Government submissions to that committee concerning harmonisation of legal systems however noted:

| “ | Differences between the legal systems of Australia and New Zealand are not a problem in themselves. The existence of such differences is the inevitable product of well-functioning democratic decision-making processes in each country, which reflect the preferences of stakeholders, and their effective voice in the law-making process.[75] | ” |

Diplomacy

The two countries and their colonial precursors have enjoyed unbroken friendly diplomatic relations over the entire period of their coexistence from the early nineteenth century up to the present. They are founding and continuing United Nations member states and they were formerly founding members of the League of Nations carrying through for the entire period until its dissolution. There is otherwise a high degree of commonality between Australia's international organisation memberships and those of New Zealand, although New Zealand may have cause for envy of Australia's acceptance to membership of the G20. There is a high degree of commonality in their co-membership of international organisations and their coparticipation as signatories of multilateral treaties of significance. They are conjoint members of a number of influential trade blocs, forums, military alliances, sharing and interoperability arrangements, and regional associations.

Both are members of the World Trade Organization, APEC, the IAEA, the East Asia Summit, the Pacific Economic Cooperation Council, the Pacific Islands Forum, the ASEAN–Australia–New Zealand Free Trade Area, the Conference on Disarmament, the International Criminal Court, the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons, INTERPOL, WIPO, the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank Group, the Global Initiative to Combat Nuclear Terrorism, the Cairns Group, the Proliferation Security Initiative, the International Hydrographic Organization, the International Maritime Organization, the International Whaling Commission, the International Organization for Migration, the International Seabed Authority, the International Fund for Agricultural Development, the OECD, the Colombo Plan, the Asian Development Bank, the Secretariat of the Pacific Community, the Pacific Regional Environment Programme, and the World Organisation for Animal Health. Both are occasional observers to ASEAN.

Both have signed and ratified the ICCPR and its First Optional Protocol and Second Optional Protocol, the Convention Against Torture, the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women and its Optional Protocol, the First Hague Convention – with Australia additionally acceding to the Second Hague Convention, the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child, the Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Relations, the Geneva Conventions, the Antarctic Treaty System, the Outer Space Treaty, the Statelessness Reduction Convention, the Genocide Convention, the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty, the Chemical Weapons Convention, the Biological Weapons Convention, the CTBT, the Treaty of Rarotonga, the Tobacco Control Treaty, UNCLOS, the Convention to Combat Desertification, the Berne Convention, the Universal Copyright Convention, the TRIPS Agreement, the Wassenaar Arrangement, the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination – with Australia additionally accepting the competency of CERD to hear individual complaints, the Framework Convention on Climate Change and Kyoto Protocol, the Ottawa Treaty, the Agreement on the Conservation of Albatrosses and Petrels, the ENMOD Convention, the London Convention, the Ramsar Convention, the Paris Convention for the Protection of Industrial Property, the Patent Cooperation Treaty, the Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs, and the Convention on Psychotropic Substances. Both voted against the adoption of the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples at the United Nations General Assembly and both have declined to sign the Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities.

New Zealand, has signed and ratified the Optional Protocol to the Convention against Torture and other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment; Australia has signed the optional protocol but has not ratified it.[76] Australia, but not New Zealand, is a member of the Nuclear Energy Agency and UNIDROIT and a party to the Patent Law Treaty, the Budapest Treaty, the WIPO Copyright Treaty, the IPC Agreement, the Statelessness Status Convention and the Moon Treaty. Whereas Australia has signed and ratified the Convention for the Conservation of Antarctic Seals, New Zealand had not ratified it as of 2003.

From 1923 to 1968 both nations along with the UK exercised trusteeship of Nauru pursuant to the Nauru Island Agreement. In the period from 2001 to 2007 New Zealand accepted certain boat arrival intending migrants to Australia for immigration processing as part of the Pacific Solution otherwise focused upon the detention centre commissioned at Nauru's Manus Island.

The two countries were the lead participants in the Regional Assistance Mission to Solomon Islands initiated from 2003.

Sport

Cricket, rugby union, rugby league & netball are the preeminent sporting rivalries. Otherwise notably, respective national teams have competed in indoor bowls, basketball, soccer, field hockey and touch football. Regular cross-Tasman competition occurs between domestic teams in men's rugby union, rugby league, soccer, and basketball, and also women's netball.

Australasian schools and school students compete in science and mathematics testing, in information technology, in writing and in English.

Gallery

-

SY Aurora – ship of the Australasian Antarctic Expedition

-

Recruitment poster urging men from the British Dominions to enlist in the Great War (1915)

-

ANZAC at ANZAC Cove on 25 April 1915

-

Southern Cross – first plane to accomplish aerial crossing of the Tasman

-

Phar Lap. New Zealand born winner of the 1930 Melbourne Cup

-

Douglas Mawson with members of BANZARE c.1930 claiming Mac Robertson Land for the Crown

-

Culmination of the first successful kayak crossings of the Tasman at New Plymouth in 2007

-

Prime Ministers of Australia and New Zealand seen at left among APEC leaders in 2007

-

The Australian High Commission in Wellington

-

The New Zealand High Commission in Canberra

-

Smoke from the Black Saturday bushfires crosses the southern Tasman Sea in February 2009

See also

- Etiquette in Australia and New Zealand

- List of articles about Australia and New Zealand jointly

- List of islands of Australia and List of islands of New Zealand

References

Sources

- Coulthard-Clark, Chris (1998). Where Australians Fought: The Encyclopaedia of Australia's Battles (First ed.). St Leonards: Allen and Unwin. ISBN 1-86448-611-2. OCLC 39097011.

- Dennis, Peter; et al. (1995). The Oxford Companion to Australian Military History. Melbourne: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-553227-9.

- Irving, Helen (1999). The Centenary Companion to Australian Federation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-57314-9.

- King, Michael (2003). The Penguin History of New Zealand. New Zealand: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-301867-4.

- Mein Smith, Philippa (2005). A Concise History of New Zealand. Australia: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-54228-6.

Citations

- ↑ "NZ, Australia 'should consider merger'". Sydney Morning Herald. 4 December 2006. Retrieved 20 March 2008.

The House of Representatives Standing Committee on Legal and Constitutional Affairs [found] "While Australia and New Zealand are of course two sovereign nations, it seems to the committee that the strong ties between the two countries – the economic, cultural, migration, defence, governmental and people-to-people linkages – suggest that an even closer relationship, including the possibility of union, is both desirable and realistic..."

- ↑ Moldofsky, Leora (30 April 2001). "Friends, Not Family: It's time for a new maturity in the trans-Tasman relationship". Time. Archived from the original on 16 March 2010. Retrieved 29 January 2014.

- ↑ Swanton, Will (23 January 2006). "25 years along, Kiwi bat sees funnier side of it". Age. Archived from the original on 15 May 2006. Retrieved 27 June 2006.

- 1 2 "Australian loses NZ apple appeal". Australian Broadcasting Corporation.

- ↑ Joint Standing Committee on the National Capital and External Territories (Parliament of Australia) "Communications with Australia's External Territories", March 1999 Archived 5 October 2009 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Keith Lewis; Scott D. Nodder; Lionel Carter (11 January 2007). "Zealandia: the New Zealand continent". Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 22 February 2007.

- ↑ Rat remains help date New Zealand's colonisation. Retrieved 23 June 2008. New Scientist.

- 1 2 3 "Cultural differences between Australia and New Zealand". Convictcreations.com. 1 April 2005.

- ↑ "New Zealand – The Youngest Country", New Zealand Tourism

- ↑ Wakefield's influence on the New Zealand Company: "Wakefield and the New Zealand Company". Early Christchurch. Christchurch City Libraries. Archived from the original on 18 March 2008. Retrieved 21 March 2008. and in relation to Wakefield's connection with South Australia: "Edward Gibbon Wakefield". The Foundation of South Australia 1800–1851. State Library of South Australia. Archived from the original on 30 July 2008. Retrieved 20 March 2008.

- ↑ There were shipping connections between relatively minor ports and New Zealand, for example "the schooner Huia, which carried hardwood from Grafton on the north coast of New South Wales to New Zealand ports and softwoods in the other direction until about 1940." + "Trans-Tasman passenger shipping operated as an extension of the Australian interstate services, most intensively between Sydney and Wellington, but also connecting other Australian and New Zealand ports. Most of the Australian coastal shipping companies were involved in the trans-Tasman trade at some stage" per Deborah Bird Rose. (2003). "Chapter 2: Ports and Shipping, 1788–1970". Linking a Nation: Australia's Transport and Communications 1788–1970. Australian Heritage Commission. ISBN 0-642-23561-9. Also illustrating the point are the many wrecks of the Union Steam Ship Company "scattered around New Zealand, Australia and the South Pacific, but nowhere more thickly than in Tasmania and the dangerous bar harbours of Greymouth and Westport" per McLean, Gavin. "Union Steam Ship Company – History & Photos". NZ Marine History. New Zealand Ship and Marine Society. Archived from the original on 21 June 2008. Retrieved 20 March 2008.

- ↑ "Australia–New Zealand Agreement of 21 January 1944". Info.dfat.gov.au. 21 January 1944.

- ↑ "New Zealand Country Brief – January 2008". Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade. January 2008. Retrieved 21 April 2008.

- ↑ "The Harriet affair – a frontier of chaos?". Ministry for Culture and Heritage. 25 January 2008.

- ↑ "The Harriet Affair". Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa.

- 1 2 Dennis et al 1995, p. 435.

- ↑ Coulthard-Clark, pp. viii–ix.

- ↑ Mercer, Phil (25 April 2002). "Australians march in honour of Gallipoli". BBC News.

- ↑ Clarke, Dr Stephen. "History of ANZAC Day". Royal New Zealand Returned and Services' Association. Archived from the original on 4 July 2007.

- ↑ Bowen, George (2001) [1997, 1999, 2000]. "4". Defending New Zealand. Auckland, New Zealand: Addison Wesley Longman. p. 12. ISBN 0-582-73940-3.

- ↑ Langford, Sue. "Encyclopedia – Appendix: The national service scheme, 1964–72". Australian War Memorial.

- ↑ Rabel, Robert (March 1999). ""We cannot afford to be left too far behind Australia": New Zealand's entry into the Vietnam War in May 1965". Journal of the Australian War Memorial (32).

- ↑ "ANZUS Alliance". h2g2 edited guide. BBC. 8 November 2005. Retrieved 22 April 2008.

- ↑ FAQs Re Light Engineer Group To Iraq, New Zealand Defence Force press release, 23 September 2004.

- ↑ Samandar, Lema (27 April 2008). "Kiwi joins his little mate on Anzac Bridge watch". Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 29 April 2008.

- ↑ "Other Monuments and Sites – New Zealand Memorial, Canberra". Historic Graves and Monuments. New Zealand Ministry for Culture and Heritage. Archived from the original on 14 March 2008. Retrieved 24 April 2008.

- ↑ Australasian Antarctic Expedition Reports:

- Benham, William Blaxland Shoppee (1921), Polychaeta, [Sydney] : Australasian Antarctic Expedition.

- Khler, René (1922), Echinodermata Ophiuroidea, Sydney : Printed by John Spence, acting government printer.

- Mawson, Douglas (1915), The Home of the Blizzard; Being the Story of the Australasian Antarctic Expedition, 1911–1914, Philadelphia, Lippincott.

- Mawson, Douglas (1918), Scientific Reports: Vol. 3, Pt. 1–6, Sydney: Govt. Printer.

- ↑ State Library of South Australia catalogue list of BANZARE reports

- ↑ Quincey, C. (1977). Tasman Trespasser. Auckland: Hodder & Stoughton.

- ↑ ""Crossing the Ditch" Trans-Tasman Kayak Expedition website". Crossingtheditch.com.au.

- ↑ "Andrew McAuley was not crazy or reckless but crossing the Tasman Sea in a kayak was a calculated, planned gamble he lost". The Age. Melbourne. 16 February 2007.

- 1 2 History of the Atlantic Cable & Undersea Communications from the first submarine cable of 1850 to the worldwide fiber optic network – New Zealand Cables

- ↑ Ron Beckett. "A Short History of Submarine Cables". Iscpc.org.

- ↑ "ANZCAN Cable System". P38arover.com. Archived from the original on 25 July 2010.

- ↑ "TASMAN 2 Cable System". P38arover.com. 19 September 2000. Archived from the original on 11 January 2012.

- ↑ "Chinese telcos plan Australia to NZ cable". Zdnet.com.au. 20 September 2011.

- ↑ Taylor, Josh (22 August 2011). "Vodafone NZ signs Pacific Fibre deal". Zdnet.com.au.

- ↑ Bingham, Eugene (13 May 2006). "No longer a 'foreign' minister". The New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 15 June 2007.

- 1 2 "Australian Department of Immigration and Citizenship Fact Sheet – New Zealanders in Australia". Immi.gov.au.

- ↑ "Kiwis overseas – Migration to Australia". Te Ara Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Archived from the original on 23 September 2007. Retrieved 12 September 2007.

- ↑ Chapman, Paul (13 May 2006). "New Zealand warned over exodus to Australia". The Daily Telegraph. UK. Retrieved 15 June 2007.

- ↑ Carl Walrond. Kiwis overseas – Migration to Australia, Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, updated 9 April 2008. Retrieved 26 January 2009.

- ↑ To stay or go to Australia – it's all down to money (Simon Collins, New Zealand Herald, 21 March 2006)

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 "2010 CER Ministerial Forum: Joint Statement". Dfat.gov.au.

- ↑ Mahne, Christian (24 July 2002). "New Zealand voters fear brain drain". Business. BBC. Retrieved 27 June 2006.

- ↑ "Welfare Payments To Be Restricted For Kiwis in Australia". ABC. 26 February 2001. Retrieved 27 June 2006.

- ↑ "'Anti-Kiwi' law slated by Aussie commission". stuff.co.nz. 16 November 2012. Retrieved 1 July 2013.

- ↑ Ross, Tara (7 February 2005). "NZ foots bill for Aussie students". The Age. Australia. Retrieved 10 January 2008.

- ↑ "Migration: permanent additions to Australia's population". 4102.0 – Australian Social Trends, 2007. Australian Bureau of Statistics. 7 August 2007. Archived from the original on 10 May 2008. Retrieved 30 May 2008.

- ↑ 1 January 2003 Australian Government Statement in relation to 'CER and Beyond' Archived 9 January 2009 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ The Spirit of CER: Part 2, 1983 to the present Archived 19 October 2009 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "About FSANZ". Foodstandards.gov.au. 12 December 2012. Archived from the original on 2 July 2009.

- ↑ "Australia-related information on Biosecurity and Quarantine from the New Zealand Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade". Mfat.govt.nz. 16 November 2010.

- ↑ "Revised ANZCERTA Rules of Origin (ROOs) – DFAT explanatory note". Dfat.gov.au.

- ↑ Joint Communique of the 2009 Australia–New Zealand Ministerial Forum (9 August 2009)

- ↑ SEM Outcomes Framework Joint Statement of the Prime Ministers of Australian and New Zealand issued 20 August 2009

- ↑ "The Proposed Importation of Fresh Apple Fruit from New Zealand: Chapter three – The Apple and Pear Industries in Australia and New Zealand" (PDF). Australian Senate – Senate Rural and Regional Affairs and Transport Committee. 18 July 2001. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 April 2011. Retrieved 26 March 2008.

- ↑ "NZ to take Australia to WTO over apple access". New Zealand Government press release. 20 August 2007. Retrieved 20 April 2008.

- ↑ "Prime Minister Kevin Rudd offends apple growers; Australia: Apple pie jokes not funny for growers". Freshplaza.com ("an independent news source for companies operating in the global fruit and vegetable sector around the world") Netherlands. 5 March 2008. Retrieved 26 March 2008.

- ↑ "Remarks by the Hon. Julie Bishop MHR to ANZLF in April 2011". Julie Bishop.

- ↑ "Description of the Sixth ANZLF convened in Sydney, Australia, on 21–22 August 2009". Dfat.gov.au.

- ↑ Donald T Brash (22 May 2000). "The Pros and Cons of Currency Union: A Reserve Bank Perspective – An address by Donald T Brash, Governor of the Reserve Bank of New Zealand, to the Auckland Rotary Club (22 May 2000)". Rbnz.govt.nz.

- ↑ Maree Chetwin, Stephen Graw and Raymond Tiong, An Introduction to the Law of Contract in New Zealand, 4th edition, Wellington: Brookers, 2006, p.2.

- ↑ House Standing Committee on Legal and Constitutional Affairs (4 December 2006). "Harmonisation of legal systems Within Australia and between Australia and New Zealand". Australian House of Representatives. Archived from the original on 29 August 2007. Retrieved 21 April 2008.

- ↑ "Report on Legal Harmonisation Tabled" (PDF) (Press release). Peter Slipper, MP, Chairman of the House of Representatives Legal and Constitutional Affairs Committee. 4 December 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 September 2007. Retrieved 21 April 2008.

- ↑ "Why New Zealand Did Not Become An Australian State". Web.archive.org. 26 October 2009. Archived from the original on 26 October 2009.

- ↑ "Why New Zealand Did Not Become An Australian State". 27 April 2005. Archived from the original on 27 April 2005. Retrieved 23 September 2007.

- ↑ The 1891 draft of the Australian Constitution specified that "aboriginal native(s)" would not be counted as part of the population. It was argued that this "would have resulted in New Zealand's having one less seat in the House of Representatives than if Maori were counted in the New Zealand population." Irving (1999), pg 403.

- ↑ Commonwealth Franchise Bill, second reading. Australian House of Representatives Hansard. Retrieved 30 July 2007.

- ↑ "New Zealand scoffs at statehood idea". BBC. 24 July 2002. Retrieved 27 June 2006.

- ↑ James, Colin (24 July 2001). "How not to waltz Matilda". Colin James. Retrieved 27 June 2006.

- ↑ James, Colin (24 July 2001). "NZ says no to federation with Australia". NZHistory, New Zealand history online. Retrieved 27 June 2006.

- ↑ Bolger sets date for NZ republic, The Independent, 17 March 1994

- ↑ Dick, Tim (5 December 2006). "Push for union with New Zealand". Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 20 February 2008. Retrieved 20 March 2008.

Australia and New Zealand should work towards a full union, or at least have a single currency and more common markets, a federal parliamentary committee says

- ↑ House Standing Committee on Legal and Constitutional Affairs (4 December 2006). "Chapter 2 Basis and mechanisms for the harmonisation of legal systems". Harmonisation of legal systems Within Australia and between Australia and New Zealand. Australian House of Representatives. Archived from the original on 29 August 2007. Retrieved 20 March 2008.

- ↑ "United Nations treaty collection 9 .b Optional Protocol to the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment". web page. United Nations. 2012. Archived from the original on 13 February 2013. Retrieved 29 December 2012.

External links

- 2010 CER Ministerial Forum: Communiqué

- Australian Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade information on New Zealand

- Australian Department of Immigration Fact Sheet – New Zealanders in Australia

- Australian High Commission in New Zealand

- New Zealand High Commission in Australia

- New Zealand Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade information on Australia