Au clair de la lune

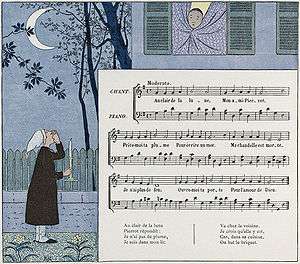

"Au clair de la lune" (French pronunciation: [o klɛʁ də la lyn(ə)],[1] lit. "By the Light of the Moon") is a French folk song of the 18th century. Its composer and lyricist are unknown. Its simple melody (![]() Play ) is commonly taught to beginners learning an instrument.

Play ) is commonly taught to beginners learning an instrument.

Lyrics

The song is now considered a lullaby for children but carries a double entendre throughout (the dead candle, the need to light up the flame, the God of Love, etc.) that becomes clear with its conclusion.

"Au clair de la lune, |

"By the light of the moon, |

In music

19th-century French composer Camille Saint-Saëns quoted the first few notes of the tune in the section "The Fossils", part of his suite The Carnival of the Animals.

Claude Debussy uses the song as a basis of his "Pierrot" from Quatre Chansons Jeunesse.

Erik Satie quoted this song in the section "Le flirt" (No. 19) of his 1914 piano collection Sports et divertissements.[2]

In 1926, Samuel Barber rewrote "H-35: Au Claire de la Lune: A Modern Setting of an old folk tune" while studying at the Curtis Institute of Music.[3]

In 1928, Marc Blitzstein orchestrated "Variations sur 'Au Claire du la Lune'."[4]

|

Au clair de la lune

1860 phonautogram by Édouard-Léon Scott de Martinville is the oldest recognizable recording of the human voice, presumably that of its creator.[5] |

| Problems playing this file? See media help. | |

In 2008, a phonautograph paper recording made by Édouard-Léon Scott de Martinville of "Au clair de la lune" on 9 April 1860, was digitally converted to sound by U.S. researchers. This one-line excerpt of the song was widely reported to have been the earliest recognizable record of the human voice and the earliest recognizable record of music.[6][7] According to those researchers, the phonautograph recording contains the beginning of the song, "Au clair de la lune, mon ami Pierrot, prête moi".[7][8][9]

In 2008, Composer Fred Momotenko composed "Au clair de la lune" as an artistic journey back in time to rediscover the original recording made on 9 April 1860.[10] It is a composition for 4-part vocal ensemble and surround audio, performed during Gaudeamus Foundation music festival at Muziekgebouw aan 't IJ. It is the second Prize winner of the Linux "150-Years-of-Music-Technology Composition Competition Prize"[11] and the special Prize winner of Festival EmuFest in Rome.

In art

In the 1804 painting and sculpting exposition, Pierre-Auguste Vafflard presented a painting of Edward Young burying his Protestant daughter-in-law by night. An anonymous commentator wrote those lyrics, which can still be heard instead of the classic "Au clair de la lune":

Au clair de la lune |

By the light of the moon |

In literature

The Ladies' Pocket Magazine (1824–1840) records:

Indeed, what must have been the chagrin and despair of this same Jaurat, when he heard sung ever night by all the little boys of Paris, that song of "Au clair de la lune," every verse of which was a remembrance of happiness to Cresson, and a reproach of cruelty to friend Peterkin, who would not open his door to his neighbor, when he requested this slight service.[12]

In his 1952 memoir Witness, Whittaker Chambers reminisced:

In my earliest recollections of her, my mother is sitting in the lamplight, in a Windsor rocking chair, in front of the parlor stove. She is holding my brother on her lap. It is bed time and, in a thin sweet voice, she is singing him into drowsiness. I am on the floor, as usual among the chair legs, and I crawl behind my mother's chair because I do not like the song she is singing and do not want her to see what it does to me. She sings: "Au clair de la lune; Mon ami, Pierrot; Prête-moi ta plume; Pour écrire un mot."Then the vowels darken ominously. My mother's voice deepens dramatically, as if she were singing in a theater. This was the part of the song I disliked most, not only because I knew that it was sad, but because my mother was deliberately (and rather unfairly, I thought) making it sadder: "Ma chandelle est morte; Je n'ai plus de feu; Ouvre-moi la porte; Pour l'amour de Dieu."

I knew, from an earlier explanation, that the song was about somebody (a little girl, I thought) who was cold because her candle and fire had gone out. She went to somebody else (a little boy, I thought) and asked him to help her for God's sake. He said no. It seemed a perfectly pointless cruelty to me.[13]

In their 1957 play Bad Seed: A Play in Two Acts, Maxwell Anderson and William March write: "A few days later, in the same apartment. The living-room is empty: Rhoda can be seen practicing 'Au Clair de la Lune' on the piano in the den."[14]

References

- ↑ Word-final E caduc is silent in modern spoken French but obligatory in older poetry and often also in singing, in which case a separate note is written for it. Therefore "lune" is pronounced differently in the name of this song than in the song itself.

- ↑ Davis, Mary E. (2008). Classic Chic: Music, Fashion, and Modernism. University of California Press. p. 87. ISBN 9780520941687.

- ↑ Heyman, Barbara B. (2012). Samuel Barber: A Thematic Catalogue of the Complete Works. Oxford University Press. p. 56.

- ↑ Pollack, Howard (2012). Marc Blitzstein: His Life, His Work, His World. Oxford University Press. p. 42.

- ↑ "FirstSounds.ORG". FirstSounds.ORG. 2008-03-27. Retrieved 2012-01-14.

- ↑ Jody Rosen (March 27, 2008). "Researchers Play Tune Recorded Before Edison". The New York Times.

- 1 2 "First Sounds archive of recovered sounds, MP3 archive". FirstSounds.org. March 2008.

- ↑ "Un papier ancien trouve sa 'voix'" (in French). Radio-Canada.ca. 28 March 2008. Retrieved 19 November 2008.

- ↑ Jean-Baptiste Roch (13 May 2008). "Le son le plus vieux du monde". Télérama (in French). Retrieved 19 November 2008.

- ↑ "Fred Momotenko".

- ↑ "Linuxaudio.org".

- ↑ M.L.B. (1835). Story of My Friend Peterkin and the Moon. London: The Ladies Pocket Magazine.

- ↑ Chambers, Whittaker (1952). Witness. New York: Random House. pp. 98–99. LCCN 52005149.

- ↑ Anderson, Maxwell; William March (1957). Bad Seed: A Play in Two Acts. New York: Dramatists Play Service. pp. 28 (act 1, scene 4).

External links

French Wikisource has original text related to this article: Au clair de la lune

French Wikisource has original text related to this article: Au clair de la lune Works related to Au clair de la lune at Wikisource

Works related to Au clair de la lune at Wikisource Media related to Au clair de la lune at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Au clair de la lune at Wikimedia Commons- Listen 1931 recording by Yvonne Printemps.

- Possibly original French lyrics