Atomoxetine

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Strattera |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a603013 |

| Pregnancy category | |

| Routes of administration | Oral |

| ATC code | N06BA09 (WHO) |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 63 to 94%[1][2][3] |

| Protein binding | 98%[1][2][3] |

| Metabolism | Hepatic, via CYP2D6[1][2][3] |

| Biological half-life | 5.2 hours[1][2][3] |

| Excretion | Renal (80%) and faecal (17%)[1][2][3] |

| Identifiers | |

| |

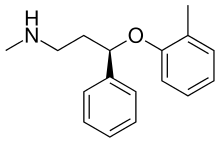

| Synonyms | (R)-N-Methyl-3-phenyl-3-(o-tolyloxy)propan-1-amine |

| CAS Number |

83015-26-3 |

| PubChem (CID) | 54841 |

| IUPHAR/BPS | 7118 |

| DrugBank |

DB00289 |

| ChemSpider |

49516 |

| UNII |

ASW034S0B8 |

| KEGG |

D07473 |

| ChEBI |

CHEBI:127342 |

| ChEMBL |

CHEMBL641 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C17H21NO |

| Molar mass |

255.36 g/mol 291.81 g/mol (hydrochloride) |

| 3D model (Jmol) | Interactive image |

| |

| |

| | |

Atomoxetine (brand name: Strattera) is a drug which is approved for the treatment of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).[4] Clinical dosages inhibit both norepinephrine and serotonin transporters.[5]

Medical use

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder

Classified as a norepinephrine (noradrenaline) reuptake inhibitor (NRI), atomoxetine is approved for use in children, adolescents, and adults.[4] However, its efficacy has not been studied in children under six years old.[2] Its primary advantage over the standard stimulant treatments for ADHD is that it has little known abuse potential.[2] While it has been shown to significantly reduce inattentive and hyperactive symptoms, the responses were lower than the response to stimulants. Additionally, 40% of participants who were treated with Atomoxetine experienced significant residual ADHD symptoms.[6]

The initial therapeutic effects of atomoxetine usually take 2–4 weeks to become apparent.[1] A further 2–4 weeks may be required for the full therapeutic effects to be seen.[7] Its efficacy may be less than that of stimulant medications.[8]

Unlike α2 adrenoceptor agonists such as guanfacine and clonidine, atomoxetine's use can be abruptly stopped without significant discontinuation effects being seen.[2]

Investigational uses

There has been some suggestion that atomoxetine might be a helpful adjunct in people with major depression, particularly in cases where ADHD occurs comorbidly to major depression.[9][10][11]

Adverse effects

Incidence of adverse effects:[2][3][12][13]

Very common (>10% incidence) adverse effects include:

- Nausea (26%)

- Xerostomia (Dry mouth) (20%)

- Appetite loss (16%)

- Insomnia (15%)

- Fatigue (10%)

- Headache

- Cough

Common (1-10% incidence) adverse effects include:

- Constipation (8%)

- Dizziness (8%)

- Erectile dysfunction (8%)

- Somnolence (sleepiness) (8%)

- Abdominal pain (7%)

- Urinary hesitation (6%)

- Tachycardia (high heart rate) (5-10%)

- Hypertension (high blood pressure) (5-10%)

- Irritability (5%)

- Abnormal dreams (4%)

- Dyspepsia (4%)

- Ejaculation disorder (4%)

- Hyperhidrosis (abnormally increased sweating) (4%)

- Vomiting (4%)

- Hot flashes (3%)

- Paraesthesia (sensation of tingling, tickling, etc.) (3%)

- Menstrual disorder (3%)

- Weight loss (2%)

- Depression

- Sinus headache

- Dermatitis

- Mood swings

Uncommon (0.1-1% incidence) adverse effects include:

- Suicide-related events

- Hostility

- Emotional lability

- Aggression

- Psychosis

- Syncope (fainting)

- Tremor

- Migraine

- Hypoaesthesia

- Seizure

- Palpitations

- Sinus tachycardia

- QT interval prolongation

- Increased blood bilirubin

- Allergic reactions

Rare (0.01-0.1% incidence) adverse effects including

- Raynaud's phenomenon

- Abnormal/increased liver function tests

- Jaundice

- Hepatitis

- Liver injury

- Acute liver failure

- Urinary retention

- Priapism[14]

- Male genital pain

The FDA of the US has issued a black box warning for suicidal behaviour/ideation.[3] Similar warnings have been issued in Australia.[2][15] Unlike stimulant medications, atomoxetine does not have abuse liability or the potential to cause withdrawal effects on abrupt discontinuation.[2]

Contraindications

Contraindications include:[2]

- Hypersensitivity to atomoxetine or any of the excipients in the product

- Symptomatic cardiovascular disease including:

- -moderate to severe hypertension

- -atrial fibrillation

- -atrial flutter

- -ventricular tachycardia

- -ventricular fibrillation

- -ventricular flutter

- -advanced arteriosclerosis

- Severe cardiovascular disorders

- Phaeochromocytoma

- Concomitant treatment with monoamine oxidase inhibitors

- Narrow angle glaucoma

- Poor metabolizers (due to the metabolism of atomoxetine by CYP2D6)

Interactions

Atomoxetine is a substrate for CYP2D6 and hence concurrent treatment with CYP2D6 inhibitors such as bupropion (Wellbutrin) or fluoxetine (Prozac) is not recommended, as this can lead to significant elevations of plasma atomoxetine levels. CYP2D6 is not very susceptible to enzyme induction.[16] Other possible drug interactions include:[2]

- Antihypertensive and pressor agents, due to the potential pressor effect of indirect sympathomimetics such as atomoxetine.

- Norepinephrine-acting agents such as α1 adrenoceptor agonists or norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors due to the potential for additive or synergistic pharmacologic effects.

- β-adrenoceptor agonists due to the potential for the effects of these drugs to be potentiated by atomoxetine.

- Highly plasma protein-bound drugs due to the potential of atomoxetine to displace these drugs from plasma proteins and hence potentiate their adverse effects. Examples include diazepam, paroxetine and phenytoin.

Overdose

Atomoxetine is relatively non-toxic in overdose. Single-drug overdoses involving over 1500 mg of atomoxetine have not resulted in death.[2] The most common symptoms of overdose include:[2]

- Gastrointestinal symptoms

- Somnolence

- Dizziness

- Tremor

- Abnormal behaviour

- Hyperactivity

- Agitation

- Dry mouth

- Tachycardia

- Hypertension

- Mydriasis

Less common symptoms:[2]

- Seizures

- QTc interval prolongation

The recommended treatment for atomoxetine overdose includes use of activated charcoal to prevent further absorption of the drug.[2]

Detection in biological fluids

Atomoxetine may be quantitated in plasma, serum or whole blood in order to distinguish extensive versus poor metabolizers in those receiving the drug therapeutically, to confirm the diagnosis in potential poisoning victims or to assist in the forensic investigation in a case of fatal overdosage.[17]

Chemistry and composition

Atomoxetine is designated chemically as (−)-N-methyl-3-phenyl-3-(o-tolyloxy)-propylamine hydrochloride, and has a molecular mass of 291.82.[4] It has a solubility of 27.8 mg/ml in water.[4] Atomoxetine is a white solid that exists as a granular powder inside the capsule, along with pregelatinized starch and dimethicone.[4] The capsule shells contain gelatin, sodium lauryl sulfate, FD&C Blue No. 2, yellow iron oxide, titanium dioxide, red iron oxide, edible black ink, and trace amounts of other inactive ingredients.[4]

-

Strattera 60-mg capsule back

-

Strattera 60-mg capsule front with Lilly logo

Pharmacology

Atomoxetine inhibits NET, SERT, and DAT with respective Ki values of 5, 77, and 1451 nM.[18] In microdialysis studies, it increased NE and DA levels by three-fold in the prefrontal cortex, but did not alter DA levels in the striatum or nucleus accumbens.[19] Atomoxetine's selective increase in NE and DA are due to a lack of high concentrations of DAT in the prefrontal cortex (where the NET transports DA instead), and the nucleus accumbens's relative paucity of NE neurons.[20] A PET imaging study of rhesus monkeys found that atomoxetine inhibited the NET and SERT with IC50 values of 31 ng/mL and 99 ng/mL plasma, respectively, and that at clinically relevant doses, atomoxetine would occupy >90% of NET and >85% of SERT.[5] Assuming that these findings translate to humans, atomoxetine would in fact be a serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI) rather than a selective NRI as has conventionally been assumed.[5]

Atomoxetine also acts as an NMDA receptor antagonist at clinically relevant doses.[21] The role of NMDA receptor antagonism in atomoxetine's therapeutic profile remains to be further elucidated, but recent literature has further implicated glutamatergic dysfunction as central in ADHD pathophysiology and etiology.[22][23] 4-Hydroxyatomoxetine, the principle metabolite of atomoxetine, exhibits relatively weak affinity for μ-opioid receptors and κ-opioid receptors. Creighton et al. reported antagonism of μ-opioid receptors and a partial agonist action at κ-opioid receptors.[24] The clinical significance of these effects are not known. Atomoxetine has been found to inhibit both brain and cardiac G protein-coupled inwardly-rectifying potassium channels, a characteristic it shares with the related drug reboxetine.[25]

| Protein | Ki (nM) for atomoxetine | Ki (nM) for 4-hydroxyatomoxetine |

|---|---|---|

| SERT | 77 | ? |

| NET | 5 | ? |

| DAT | 1451 | ? |

| 5-HT receptors | >1000 | ? |

| Alpha adrenergic receptors | >1000 | ? |

| Beta adrenergic receptors | >1000 | ? |

| D1 & D2 | >1000 | ? |

| M1 & M2 | >1000 | ? |

| H1 & H2 | >1000 | ? |

| δ1 opioid receptor | ? | 300 |

| κ1 opioid receptor | ? | 95 |

| μ opioid receptor | ? | 422 |

| σ1 receptor | >1000 | ? |

History

Atomoxetine is manufactured, marketed, and sold in the United States as the hydrochloride salt (atomoxetine HCl) under the brand name Strattera by Eli Lilly and Company, the original patent-filing company and current U.S. patent owner. Atomoxetine initially intended to be developed as an antidepressant, but it was found to be insufficiently efficacious for treating depression. It was, however, found to be effective for ADHD and was approved by the FDA in 2002 for the treatment of ADHD. No generic is manufactured directly in the United States since it is under patent until 2017.[27] On 12 August 2010, Lilly lost a lawsuit that challenged its patent on Strattera, increasing the likelihood of an earlier entry of a generic into the US market.[28] On 1 September 2010, Sun Pharmaceuticals announced it would begin manufacturing a generic in the United States.[29] In a 29 July 2011 conference call, however, Sun Pharmaceutical's Chairman stated "Lilly won that litigation on appeal so I think [generic Strattera]’s deferred."[30]

Brand names

In India, atomoxetine is sold under brand names including Attentrol [Sun Pharma], Axepta, [Intas Pharma] Attera [Icon pharma], Tomoxetin [Torrent Pharma], Atokem [Alkem Pharma], and Attentin [Ranbaxy Pharma].

In Romania, atomoxetine is sold under the brand name Strattera and as a generic made by Sun Pharmaceuticals.

In Iran, atomoxetine is sold under brand names including stramox by TeKaJe Co.

See also

- Orphenadrine (modified base and similar termination of the molecule) it is a variant of the same structure

- Fluoxetine (modified base and same termination of the molecule)

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "atomoxetine (Rx) – Strattera". Medscape Reference. WebMD. Retrieved 10 November 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 "STRATTERA® (atomoxetine hydrochloride)". TGA eBusiness Services. Eli Lilly Australia Pty. Limited. 21 August 2013. Retrieved 10 November 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "ATOMOXETINE HYDROCHLORIDE capsule [Mylan Pharmaceuticals Inc.]". DailyMed. Mylan Pharmaceuticals Inc. October 2011. Retrieved 10 November 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "STRATTERA® (atomoxetine hydrochloride) CAPSULES for Oral Use. Full Prescribing Information" (PDF). Indianapolis, USA: Eli Lilly and Company. 20 February 2014. Retrieved 23 May 2014.

- 1 2 3 Ding, Y.-S.; Naganawa, M.; Gallezot, J.-D.; Nabulsi, N.; Lin, S.-F.; Ropchan, J.; Weinzimmer, D.; McCarthy, T.J.; Carson, R.E.; Huang, Y.; Laruelle, M. (2014). "Clinical doses of atomoxetine significantly occupy both norepinephrine and serotonin transports: Implications on treatment of depression and ADHD". NeuroImage. 86: 164–171. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.08.001. ISSN 1053-8119.

- ↑ Ghuman, Jaswinder K.; Hutchison, Shari L. (2014-11-01). "Atomoxetine is a second-line medication treatment option for ADHD". Evidence Based Mental Health. 17 (4): 108–108. doi:10.1136/eb-2014-101805. ISSN 1468-960X. PMID 25165169.

- ↑ Taylor, D; Paton, C; Shitij, K (2012). The Maudsley prescribing guidelines in psychiatry. West Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-0-470-97948-8.

- ↑ Kooij, JJS (2013). Adult ADHD Diagnostic Assessment and Treatment (PDF). Springer London. doi:10.1007/978-1-4471-4138-9. ISBN 978-1-4471-4137-2.

- ↑ Spencer TJ, Faraone SV, Michelson D, Adler LA, Reimherr FW, Glatt SJ & Biederman J (March 2006). "Atomoxetine and adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: the effects of comorbidity". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 67 (3): 415–20. doi:10.4088/JCP.v67n0312. PMID 16649828.

- ↑ Carpenter LL, Milosavljevic N, Schecter JM, Tyrka AR, Price LH (October 2005). "Augmentation with open-label atomoxetine for partial or non-response to antidepressants". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 66 (10): 1234–8. doi:10.4088/JCP.v66n1005. PMID 16259536.

- ↑ Kratochvil CJ, Newcorn JH, Arnold LE, Duesenberg D, Emslie GJ, Quintana H, Sarkis EH, Wagner KD, Gao H, Michelson D & Biederman J (September 2005). "Atomoxetine alone or combined with fluoxetine for treating ADHD with comorbid depressive or anxiety symptoms". Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 44 (9): 915–24. doi:10.1097/01.chi.0000169012.81536.38. PMID 16113620.

- ↑ "Strattera 10mg, 18mg, 25mg, 40mg, 60mg, 80mg or 100mg hard capsules". electronic Medicines Compendium. 28 May 2013. Retrieved 10 November 2013.

- ↑ "Strattera Product Insert". Retrieved 8 December 2013.

- ↑ "STRATTERA Medication Guide" (PDF). Eli Lilly and Company. 2003. Retrieved 17 December 2013.

- ↑ "Atomoxetine and suicidality in children and adolescents". Australian Prescriber. 36 (5). October 2013. p. 166. Archived from the original on 10 November 2013. Retrieved 10 November 2013.

- ↑ Horn, John R.; Hansten, Philip D. (2008). "Get to Know an Enzyme: CYP2D6". Pharmacy Times. Retrieved 19 February 2015.

- ↑ Baselt, Randall C. (2008). Disposition of Toxic Drugs and Chemicals in Man (8th ed.). Foster City, CA: Biomedical Publications. pp. 118–20. ISBN 0-931890-08-X.

- 1 2 Roth, BL; Driscol, J (12 January 2011). "PDSP Ki Database". Psychoactive Drug Screening Program (PDSP). University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and the United States National Institute of Mental Health. Archived from the original on 8 November 2013. Retrieved 10 November 2013.

- 1 2 Bymaster, FP; Katner, JS; Nelson, DL; Hemrick-Luecke, SK; Threlkeld, PG; Heiligenstein, JH; Morin, SM; Gehlert, DR; Perry, KW (November 2002). "Atomoxetine Increases Extracellular Levels of Norepinephrine and Dopamine in Prefrontal Cortex of Rat: A Potential Mechanism for Efficacy in Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder" (PDF). Neuropsychopharmacology. 27 (5): 699–711. doi:10.1016/S0893-133X(02)00346-9. PMID 12431845.

- ↑ Stahl, Stephen M. (17 March 2008). "17". Stahl's Essential Psychopharmacology: Neuroscientific Basis and Practical Applications (3rd ed.). New York: Cambridge University Press. p. 891. ISBN 9780521673761. Retrieved 1 November 2015.

Since the prefrontal cortex lacks high concentrations of DAT, DA is inactivated in this part of the brain by NET. Thus, inhibiting NET increases both DA and NE in the prefrontal cortex (Figures 12-36 and 17-21). However, since there are only a few NE neurons and NETs in nucleus accumbens, inhibiting NET does not lead to an increase in either NE or DA there (Figure 17-21). For this reason, in ADHD patients with deficient arousal and weak NE and DA signals in prefrontal cortex, a selective NRI such as atomoxetine increases both NE and DA in prefrontal cortex, enhancing tonic signaling of both, but it increases neither NE nor DA in the nucleus accumbens. Therefore atomoxetine has no abuse potential.

- ↑ Ludolph, AG; Udvardi, PT; Schaz, U; Henes, C; Adolph, O; Weigt, HU; Fegert, JM; Boeckers, TM; Föhr, KJ (May 2010). "Atomoxetine acts as an NMDA receptor blocker in clinically relevant concentrations" (PDF). British Journal of Pharmacology. 160 (2): 283–291. doi:10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.00707.x. PMC 2874851

. PMID 20423340.

. PMID 20423340. - ↑ Lesch, KP; Merker, S; Reif, A; Novak, M (June 2013). "Dances with black widow spiders: dysregulation of glutamate signalling enters centre stage in ADHD". European Neuropsychopharmacology. 23 (6): 479–491. doi:10.1016/j.euroneuro.2012.07.013. PMID 22939004.

- ↑ "New gene study of ADHD points to defects in brain signaling pathways". Children's Hospital of Philadelphia. 4 December 2011.

- 1 2 Creighton, CJ; Ramabadran, K; Ciccone, PE; Liu, J; Orsini, MJ; Reitz, AB (2 August 2004). "Synthesis and biological evaluation of the major metabolite of atomoxetine: elucidation of a partial kappa-opioid agonist effect.". Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry Letters. 14 (15): 4083–5. doi:10.1016/j.bmcl.2004.05.018. PMID 15225731.

- ↑ Kobayashi, T; Washiyama, K; Ikeda, K (Jun 2010). "Inhibition of G-protein-activated inwardly rectifying K+ channels by the selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors atomoxetine and reboxetine.". Neuropsychopharmacology. 35 (7): 1560–9. doi:10.1038/npp.2010.27. PMC 3055469

. PMID 20393461.

. PMID 20393461. - ↑ Bymaster, FP; Katner, JS; Nelson, DL; Hemrick-Luecke, SK; Threlkeld, PG; Heiligenstein, JH; Morin, SM; Gehlert, DR; Perry, KW (November 2002). "Atomoxetine increases extracellular levels of norepinephrine and dopamine in prefrontal cortex of rat: a potential mechanism for efficacy in attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder". Neuropsychopharmacology. 27 (5): 699–711. doi:10.1016/S0893-133X(02)00346-9. PMID 12431845.

- ↑ "Patent and Exclusivity Search Results". Electronic Orange Book. US Food and Drug Administration. Retrieved 26 April 2009.

- ↑ "Drugmaker Eli Lilly loses patent case over ADHD drug, lowers revenue outlook". Chicago Tribune.

- ↑ "Sun Pharma receives USFDA approval for generic Strattera capsules". International Business Times. Archived from the original on 7 April 2011.

- ↑ "Sun Pharma Q1 2011-12 Earnings Call Transcript 10.00 am, July 29, 2011" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 September 2011.

External links

- Strattera by Eli Lilly and Company

- RxList.com – Strattera

- Detailed Strattera Consumer Information: Uses, Precautions, Side Effects

- All disclosed Lilly trials

- MSDS for Atomoxetine HCl

- Strattera Related Published Studies