Atlantic salmon

| Atlantic salmon | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Actinopterygii |

| Order: | Salmoniformes |

| Family: | Salmonidae |

| Genus: | Salmo |

| Species: | S. salar |

| Binomial name | |

| Salmo salar Linnaeus, 1758 | |

| |

| Distribution of Atlantic salmon | |

The Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) is a species of ray-finned fish in the family Salmonidae. It is found in the northern Atlantic Ocean, in rivers that flow into the north Atlantic and, due to human introduction, in the north Pacific Ocean.[2][3] Atlantic salmon have long been the target of recreational and commercial fishing, and this, as well as habitat destruction, has reduced their numbers significantly; the species is the subject of conservation efforts in several countries.

Nomenclature

The Atlantic salmon was given its scientific binomial name by zoologist and taxonomist Carl Linnaeus in 1758. The name, Salmo salar, derives from the Latin salmo, meaning salmon, and salar, meaning leaper, according to M. Barton,[4] but more likely meaning "resident of salt water". Lewis and Short's Latin Dictionary (Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1879) translates salar as a kind of trout from its use in the Idylls of the poet Ausonius (4th century CE). Later, the differently coloured smolts were found to be the same species.

Other names used to reference Atlantic salmon are: bay salmon, black salmon, caplin-scull salmon, Sebago salmon, silver salmon, fiddler, or outside salmon. At different points in their maturation and life cycle, they are known as parr, smolt, grilse, grilt, kelt, slink, and spring salmon. Atlantic salmon that do not journey to sea are known as landlocked salmon or ouananiche.

Description

The species is the longest and heaviest in genus Salmo. After two years at sea, the fish average 71 to 76 cm (28 to 30 in) in length and 3.6 to 5.4 kg (7.9 to 11.9 lb) in weight.[5] But specimens can be much larger. An Atlantic salmon netted in 1960 in Scotland, in the estuary of the river Hope, was weighed in at 49.44 kg (109.0 lb), while another netted in 1925 in Norway measured 160.65 cm (63.25 in) in length.[6]

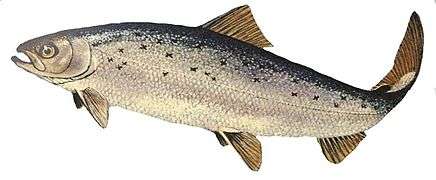

The colouration of young Atlantic salmon does not resemble the adult stage. While they live in fresh water, they have blue and red spots. At maturity, they take on a silver-blue sheen. The easiest way of identifying them as an adult is by the black spots predominantly above the lateral line, though the caudal fin is usually unspotted. When they reproduce, males take on a slight green or red colouration. The salmon has a fusiform body, and well-developed teeth. All fins, save the adipose, are bordered with black.

Distribution and habitat

The distribution of Atlantic salmon depends on water temperature. Because of climate change, some of the species' southern populations, in Spain and other warm countries, are growing smaller[8][9] and are expected to be extirpated soon. Before human influence, the natural breeding grounds of Atlantic salmon were rivers in Europe and the eastern coast of North America. When North America was settled by Europeans, eggs were brought on trains to the west coast and introduced into the rivers there. Other attempts to bring Atlantic salmon to new settlements were made; e.g. New Zealand. But since there are no suitable ocean currents on New Zealand, most of these introductions failed. There is at least one landlocked population of Atlantic salmon on New Zealand, where the fish never go out to sea.

Young salmon spend one to four years in their natal river. When they are large enough (c. 15 centimetres (5.9 in)), they smoltify, changing camouflage from stream-adapted with large, gray spots to sea-adapted with shiny sides. They also undergo some endocrinological changes to adapt to osmotic differences between fresh water and seawater habitat. When smoltification is complete, the parr (young fish) now begin to swim with the current instead of against it. With this behavioral change, the fish are now referred to as smolt. When the smolt reach the sea, they follow sea surface currents and feed on plankton or fry from other fish species such as herring. During their time at sea, they can sense the change in the Earth magnetic field through iron in their lateral line.

When they have had a year of good growth, they will move to the sea surface currents that transport them back to their natal river. It is a major misconception that salmon swim thousands of kilometers at sea; instead they surf through sea surface currents. When they reach their natal river they find it by smell; only 5% of Atlantic salmon go up the wrong river. Thus, the habitat of Atlantic salmon is the river where they are born and the sea surface currents that are connected to that river in a circular path.

Wild salmon disappeared from many rivers during the twentieth century due to overfishing and habitat change.[2] By 2000 the numbers of Atlantic salmon had dropped to critically low levels.[10]

Diet

Young salmon begin a feeding response within a few days. After the yolk sac is absorbed by the body, they begin to hunt. Juveniles start with tiny invertebrates, but as they mature, they may occasionally eat small fish. During this time, they hunt both in the substrate and in the current. Some have been known to eat salmon eggs. The most commonly eaten foods include caddisflies, blackflies, mayflies, and stoneflies.[2]

As adults, the fish feed on much larger food: Arctic squid, sand eels, amphipods, Arctic shrimp, and sometimes herring, and the fishes' size increases dramatically.[2]

Behavior

Fry and parr have been said to be territorial, but evidence showing them to guard territories is inconclusive. While they may occasionally be aggressive towards each other, the social hierarchy is still unclear. Many have been found to school, especially when leaving the estuary.

Adult Atlantic salmon are considered much more aggressive than other salmon, and are more likely to attack other fish than others. A matter of concern is where they have become an invasive threat, attacking native salmon, such as Chinook salmon and coho salmon.[2]

Life stages

Most Atlantic salmon follow an anadromous fish migration pattern,[3] in that they undergo their greatest feeding and growth in saltwater; however, adults return to spawn in native freshwater streams where the eggs hatch and juveniles grow through several distinct stages.

Atlantic salmon do not require saltwater. Numerous examples of fully freshwater (i.e., "landlocked") populations of the species exist throughout the Northern Hemisphere,[3] including a now extinct population in Lake Ontario, which have been shown in recent studies to have spent their entire life cycle in watershed of the lake.[11] In North America, the landlocked strains are frequently known as ouananiche.

Freshwater phase

The freshwater phases of Atlantic salmon vary between one and eight years, according to river location.[12] While the young in southern rivers, such as those to the English Channel, are only one year old when they leave, those further north, such as in Scottish rivers, can be over four years old, and in Ungava Bay, northern Quebec, smolts as old as eight years have been encountered.[12] The average age correlates to temperature exceeding 7 °C (45 °F).[2]

The first phase is the alevin stage, when the fish stay in the breeding ground and use the remaining nutrients in their yolk sacs. During this developmental stage, their young gills develop and they become active hunters. Next is the fry stage, where the fish grow and subsequently leave the breeding ground in search of food. During this time, they move to areas with higher prey concentration. The final freshwater stage is when they develop into parr, in which they prepare for the trek to the Atlantic Ocean.

During these times, the Atlantic salmon are very susceptible to predation. Nearly 40% are eaten by trout alone. Other predators include other fish and birds.

Saltwater phases

When parr develop into smolt, they begin the trip to the ocean, which predominantly happens between March and June. Migration allows acclimation to the changing salinity. Once ready, young smolt leave, preferring an ebb tide.

Having left their natal streams, they experience a period of rapid growth during the one to four years they live in the ocean. Typically, Atlantic salmon migrate from their home streams to an area on the continental plate off West Greenland. During this time, they face predation from humans, seals, Greenland sharks, skate, cod, and halibut. Some dolphins have been noticed playing with dead salmon, but it is still unclear whether they consume them.

Once large enough, Atlantic salmon change into the grilse phase, when they become ready to return to the same freshwater tributary they departed from as smolts. After returning to their natal streams, the salmon will cease eating altogether prior to spawning. Although largely unknown, odor – the exact chemical signature of that stream – may play an important role in how salmon return to the area where they hatched. Once heavier than about 250 g, the fish no longer become prey for birds and many fish, although seals do prey upon them. Grey and common seals commonly eat Atlantic salmon. Survivability to this stage has been estimated at between 14 and 53%.[2]

-

Very young fertilized salmon eggs, notice the developing eyes and neural tube

-

Newly hatched alevin feed on their yolk sacs

-

The fry become parr, and pick home rocks or plants in the streambed from which they dart out to capture insect larvae and other passing food

-

When the parr are ready for migration to the ocean, they become smolt

Breeding

Atlantic salmon breed in the rivers of Western Europe from northern Portugal north to Norway, Iceland, and Greenland, and the east coast of North America from Connecticut in the United States north to northern Labrador and Arctic Canada.

The species constructs a nest or "redd" in the gravel bed of a stream. The female creates a powerful downdraught of water with her tail near the gravel to excavate a depression. After she and a male fish have eggs and milt (sperm), respectively, upstream of the depression, the female again uses her tail, this time to shift gravel to cover the eggs and milt which have lodged in the depression.

Unlike the various Pacific salmon species which die after spawning (semelparous), the Atlantic salmon is iteroparous, which means the fish may recondition themselves and return to the sea to repeat the migration and spawning pattern several times, although most spawn only once or twice.[3][13] Migration and spawning exact an enormous physiological toll on individuals, such that repeat spawners are the exception rather than the norm.[13] Atlantic salmon show high diversity in age of maturity and may mature as parr, one- to five-sea-winter fish, and in rare instances, at older sea ages. This variety of ages can occur in the same population, constituting a ‘bet hedging’ strategy against variation in stream flows. So in a drought year, some fish of a given age will not return to spawn, allowing that generation other, wetter years in which to spawn.[12]

Hybridization

When in shared breeding habitats, Atlantic salmon will hybridize with brown trout (Salmo trutta).[14][15][16] Hybrids between Atlantic salmon and brown trout were detected in two of four watersheds studied in northern Spain. The proportions of hybrids in samples of 'salmon' ranged from 0 to 7-7% but they were not significantly heterogeneous among locations, resulting in a mean hybridization rate of 2-3%. This is the highest rate of natural hybridization so far reported and is significantly greater than rates observed elsewhere in Europe.[17]

Aquaculture

In its natal streams, Atlantic salmon are considered prized recreational fish, pursued by fly anglers during its annual runs. At one time, the species supported an important commercial fishery and a supplemental food fishery. However, the wild Atlantic salmon fishery is commercially dead; after extensive habitat damage and overfishing, wild fish make up only 0.5% of the Atlantic salmon available in world fish markets. The rest are farmed, predominantly from aquaculture in Norway, Chile, Canada, the UK, Ireland, Faroe Islands, Russia and Tasmania in Australia. Sport fishing communities, mainly from Iceland and Scandinavia, have joined in the North Atlantic Salmon Fund to buy away commercial quotas in an effort to save the wild species of Salmo salar.[13]

Process

Adult male and female fish are anaesthetised; their eggs and sperm are "stripped" after the fish are cleaned and cloth dried. Sperm and eggs are mixed, washed, and placed into freshwater. Adults recover in flowing, clean, well-aerated water.[18] Some researchers have even studied cryopreservation of their eggs.[19]

Fry are generally reared in large freshwater tanks for 12 to 20 months. Once the fish have reached the smolt phase, they are taken out to sea, where they are held for up to two years. During this time, the fish grow and mature in large cages off the coasts of Canada, the USA, or parts of Europe.[13]

Generally, cages are made of two nets. Inner nets, which wrap around the cages, hold the salmon. Outer nets, which are held by floats, keep predators out.[18]

Controversy

Some Atlantic salmon escape from cages at sea. These salmon tend to lessen the genetic diversity of the species leading to lower survival rates, and lower catch rates. On the west coast of North America, the non-native salmon can be an invasive threat, especially in Alaska and parts of Canada. This causes them to compete with native salmon for resources. Extensive efforts are underway to prevent the spread of Atlantic salmon in the Pacific and elsewhere.[20]

On the west coast of northern America, aquaculturists have taken care to ensure the non-native salmon cannot escape from their open-net pens, and escape is no longer considered a major concern. Evidence of Atlantic salmon surviving and establishing wild populations in the Pacific is lacking.

From 1905 until 1935, in excess of 8.6 million Atlantic salmon of various life stages (predominantly advanced fry) were intentionally introduced to more than 60 individual British Columbia lakes and streams. Historical records indicate, in a few instances, mature sea-run Atlantic salmon were captured in the Cowichan River; however, a self-sustaining population never materialized. Environmental assessments by the US National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS), the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife and the BC Environmental Assessment Office have concluded the potential risk of Atlantic salmon colonization in the Pacific Northwest is low.[21]

Human impact

.jpg)

Atlantic salmon were once abundant throughout the North Atlantic. European fishermen gillnetted for Atlantic salmon in rivers using hand-made nets for at least several centuries.[22] Wood and stone weirs along streams and ponds were used for millennia to harvest salmon in the rivers of Maine and New England,[23] and gillnetting was an early fishing technology in colonial America.[24]

Human activities have heavily damaged salmon populations across their range. The major impacts were from overfishing and habitat change, and the new threat from competitive farmed fish. Salmon decline in Lake Ontario goes back to the 18th–19th centuries, due to logging and soil erosion, as well as dam and mill construction. By 1896, the species was declared extirpated from the lake.[25][11] When dams were constructed on the Oswego River, their spawning areas were cut off and they went extinct locally.

In the 1950s, salmon from rivers in the United States and Canada, as well as from Europe, were discovered to gather in the sea around Greenland and the Faroe Islands. A commercial fishing industry was established, taking salmon using drift nets. After an initial series of record annual catches, the numbers crashed; between 1979 and 1990, catches fell from four million to 700,000.[26] Overfishing at sea is generally considered the primary factor.

Beginning around 1990, the rates of Atlantic salmon mortality at sea more than doubled. In the western Atlantic, fewer than 100,000 of the important multiple sea-winter salmon were returning. Rivers of the coast of Maine, southern New Brunswick and much of mainland Nova Scotia saw runs drop precipitously, and even disappear. To find out more about the increased mortality rate, a concerted international effort has been organized by the North Atlantic Salmon Conservation Organization.[27]

Possibly because of improvements in ocean feeding grounds, returns in 2008 were positive. On the Penobscot River in Maine, returns were about 940 in 2007, and by mid-July 2008, the return was 1,938. Similar stories were reported in rivers from Newfoundland to Quebec. In 2011, more than 3,100 salmon returned to the Penobscot, the most since 1986, and nearly 200 ascended the Narraguagus River, up from the low two digits just a decade before.[28]

Recovery

Around the North Atlantic, efforts to restore salmon to their native habitats are underway, with slow progress. Habitat restoration and protection are key to this process, but issues of excessive harvest and competition with farmed and escaped salmon are also primary considerations. In the Great Lakes, Atlantic salmon have been introduced successfully, but the percentage of salmon reproducing naturally is very low. Most are stocked annually. Atlantic salmon were native to Lake Ontario, but were extirpated by habitat loss and overfishing in the late 19th century. The state of New York has since stocked its adjoining rivers and tributaries, and in many cases does not allow active fishing.[3][20]

Historically, the Housatonic River, and its Naugatuck River tributary, hosted the southernmost Atlantic salmon spawning runs in the United States.[29][30] However, there are historical accounts as early as 1609 from Henry Hudson that Atlantic salmon once ran up the Hudson River.[31]

In the early 1990s, Carlson challenged the notion that Atlantic salmon were prehistorically abundant in New England, when the climate was warmer as it is now. This idea was based on a paucity of bone data in archaeological sites relative to other fish species and claimed that historical observer records were exaggerated.[32][33] However, arguments that lack of archaeological bone fragments rule out historic abundance are more recently disputed because salmon bones are rare at sites that still have large salmon runs, salmonid bones in general are poorly recovered relative to other fish species, and that salmon remains may have been diluted by the large numbers of other anadromous fishes using northeastern streams.[34][35] In addition, fish scale evidence dating to 10,000 years BP places Atlantic salmon in a coastal New Jersey pond.[36]

In New England, many efforts are underway to restore salmon to the region by knocking down obsolete dams and updating others with fish ladders and other techniques that have proven effective in the West with Pacific salmon. There is some success thus far, with populations growing in the Penobscot and Connecticut Rivers. Lake Champlain now has Atlantic salmon. In Ontario, the Atlantic Salmon Restoration Program[37] was started in 2006, and is one of the largest freshwater conservation programs in North America. It has stocked Lake Ontario with over 700,000 young Atlantic salmon. Recent documented successes in the reintroduction of Atlantic salmon include the following:

- In October 2007, salmon were video-recorded running in Toronto's Humber River by the Old Mill.[25]

- A migrating salmon was observed in Ontario's Credit River in November 2007.[25]

- As of 2013, there has been some success in establishing Atlantic salmon in Fish Creek, a tributary of Oneida Lake in central New York.[38]

- In November 2015, salmon nests were observed in Connecticut in the Farmington River, a tributary of the Connecticut River where Atlantic salmon had not been observed spawning since "probably the Revolutionary War".[39] A 45-year, $25 million federal government effort to restore wild Atlantic salmon to the Connecticut River watershed was discontinued in 2012, but now appears to have been successful.[40]

Atlantic salmon still remains a popular fish for human consumption.[3] It is commonly sold fresh, canned, or frozen.

Beaver impact

The decline in anadromous salmonid species over the last two to three centuries is correlated with the decline in the North American beaver and European beaver, although some fish and game departments continue to advocate removal of beaver dams as potential barriers to spawning runs. Migration of adult Atlantic salmon may be limited by beaver dams during periods of low stream flows, but the presence of juvenile Salmo salar upstream from the dams suggests the dams are penetrated by parr.[41] Downstream migration of Atlantic salmon smolts was similarly unaffected by beaver dams, even in periods of low flows.[41]

In a 2003 study, Atlantic salmon and sea-run brown trout/sea trout spawning in the Numedalslågen River and 51 of its tributaries in southeastern Norway were unhindered by beavers.[42] In a restored, third-order stream in northern Nova Scotia, beaver dams generally posed no barrier to Atlantic salmon migration except in the smallest upstream reaches in years of low flow where pools were not deep enough to enable the fish to leap the dam or without a column of water over-topping the dam for the fish to swim up.[43]

The importance of winter habitat to salmonids afforded by beaver ponds may be especially important in streams of northerly latitudes without deep pools where ice cover makes contact with the bottom of shallow streams.[41] In addition, the up to eight-year-long residence time of juveniles in freshwater may make beaver-created permanent summer pools a crucial success factor for Atlantic salmon populations. In fact, two-year-old Atlantic salmon parr in beaver ponds in eastern Canada showed faster summer growth in length and mass and were in better condition than parr upstream or downstream from the pond.[44]

Legislation

The first laws regarding the Atlantic salmon were started nearly 800 years ago.

England and Wales

Edward I instituted a penalty for collecting salmon during certain times of the year. His son Edward II continued, regulating the construction of weirs. Enforcement was overseen by those appointed by the justices of the peace. Because of confusing laws and the appointed conservators having little power, most laws were barely enforced.

Based on this, a royal commission was appointed in 1860 to thoroughly investigate the Atlantic salmon and the laws governing the species, resulting in the 1861 Salmon Fisheries Act. The act placed enforcement of the laws under the Home Office's control, but it was later transferred to the Board of Trade, and then later to the Board of Agriculture and Fisheries.

Another act passed in 1865 imposed charges to fish and catch limits. It also caused the formation of local boards having jurisdiction over a certain river. The next significant act, passed in 1907, allowed the board to charge 'duties' to catch other freshwater fish, including trout.

Despite legislation, board effects decreased until, in 1948, the River Boards Act gave authority of all freshwater fish and the prevention of pollution to one board per river. In total, it created 32 boards.

In 1974, the 32 boards were reduced to 10 regional water authorities (RWAs). Although only the Northumbrian, Welsh, northwest and southwest RWA's had considerable salmon populations, all ten also cared for trout and freshwater eels.

The Salmon and Freshwater Fisheries Act was passed in 1975. Among other things, it regulated fishing licences, seasons, and size limits, and banned obstructing the salmon's migratory paths.[2]

Scotland

Legislation in Scotland to help Atlantic salmon began in 1318 by Alexander II. It prohibited certain types of traps in rivers.

During the 15th century, many laws were passed; many regulated fishing times, and worked to ensure smolts could safely pass downstream. James III even closed a meal mill because of its history of killing fish attracted to the wheel. Because the fish were held in such high regard, poachers were severely punished.

More recent legislation has established commissioners who manage districts. Furthermore, the Salmon and Freshwater Fisheries Act in 1951 required the Secretary of State be given data about the catches of salmon and trout to help establish catch limits.[2][18]

United States

Several populations of Atlantic salmon are in serious decline, and are listed as endangered under the Endangered Species Act (ESA). Currently, runs of 11 rivers in Maine are on the list – Kennebec, Androscoggin, Penobscot, Sheepscot, Ducktrap, Cove Brook, Pleasant, Narraguagus, Machias, East Machias and Dennys. The Penobscot River is the "anchor river" for Atlantic salmon populations in the US. Returns in 2008 have been around 2,000, more than double the 2007 return of 940.

Section 9 of the ESA makes it illegal to take an endangered species of fish or wildlife. The definition of "take" is to "harass, harm, pursue, hunt, shoot, wound, kill, trap, capture, or collect, or to attempt to engage in any such conduct".[45]

Canada

The federal government has prime responsibility for protecting the Atlantic salmon, but over the last generation, effort has continued to shift management as much as possible to provincial authorities through memoranda of understanding, for example. A new Atlantic salmon policy is in the works, and in the past three years, the government has attempted to pass a new version of the century-old Fisheries Act through Parliament.

Federal legislation regarding at-risk populations is weak. Inner Bay of Fundy Atlantic salmon runs were declared endangered in 2000. As of 2008, no recovery plan is in place.

It takes constant pressure from nongovernmental organizations, such as the Atlantic Salmon Federation, for improvements in management, and for initiatives to be considered. For example, the technology for mitigation of acid rain-affected rivers used in Norway is needed in 54 Nova Scotia rivers. Yet, an initiative of the ASF and the Nova Scotia Salmon Association raised the funds to get a project in place, in West River-Sheet Harbour.

In Quebec, the daily catch limit for Atlantic salmon is one fish over 63 cm (25 in), two fish under 63 cm (25 in) or one fish over and one under 63 cm (25 in), provided the smaller fish was the first one caught (a provision designed to prevent an angler from continuing to fish if a large fish is already in possession). The annual catch limit is seven Atlantic salmon of any size.

In Lake Ontario, the historic populations of Atlantic salmon became extinct, and cross-national efforts have been under way to reintroduce the species, with some areas already having restocked naturally reproducing populations.[46][47]

NASCO

The North Atlantic Salmon Conservation Organization is an international council made up of Canada, the European Union, Iceland, Norway, the Russian Federation, and the United States, with its headquarters in Edinburgh.[48] It was established in 1983 to help protect Atlantic salmon stocks, through the cooperation between nations. They work to restore habitat and promote conservation of the salmon.

Sustainable consumption

In 2010, Greenpeace International has added the Atlantic salmon to its seafood red list. "The Greenpeace International seafood red list is a list of fish that are commonly sold in supermarkets around the world, and which have a very high risk of being sourced from unsustainable fisheries".[49]

See also

- AquAdvantage salmon, a genetically modified Atlantic salmon

- Atlantic Salmon Federation (ASF)

- Salmon as food

Notes

- ↑ Baillie, J. and Groombridge, B. (1996). "Salmo salar". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. IUCN. 1996: e.T14144A4408913. doi:10.2305/iucn.uk.1996.rlts.t19855a9026693.en. Retrieved 26 August 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Shearer, W. (1992). The Atlantic Salmon. Halstead Press.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 The Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Fishes, Whales & Dolphins. Chanticleer Press. 1983. p. 395.

- ↑ Barton, M.: "Biology of Fishes.", pages 198–202 Thompson Brooks/Cole 2007

- ↑ "Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar)". NOAA Fisheries - Office of Protected Resources.

- ↑ "Buller F, The Domesday Book of Giant Salmon Volume 1 & 2. Constable (2007) & Constable (2010)

- ↑ Atlantic Salmon Life Cycle Connecticut River Coordinator's Office, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Updated: 13 September 2010.

- ↑ "Same number of fishermen, but less salmon in Spanish rivers". science daily. August 26, 2011. Retrieved April 30, 2016.

- ↑ J. L. Horreo, G. Machado-Schiaffino, A. M. Griffiths, D. Bright, J. R. Stevens, E. Garcia-Vazquez. (2011). "Atlantic Salmon at Risk: Apparent Rapid Declines in Effective Population Size in Southern European Populations.". Transactions of the American Fisheries Society, 2011; 140 (3): 605 DOI: 10.1080/00028487.2011.585574.

- ↑ B. Dempson, C. J. Schwarz, D. G. Reddin, M. F. O’Connell, C. C. Mullins, and C. E. Bourgeois (2001). "Estimation of marine exploitation rates on Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar L.) stocks in Newfoundland, Canada" (PDF). ICES Journal of Marine Science: 331–341. doi:10.1006/jmsc.2000.1014. Retrieved 7 May 2011.

- 1 2 "Study sheds light on extinct Lake Ontario salmon". Toronto Star, November 9, 2016, page GT1.

- 1 2 3 Klemetsen A, Amundsen P-A, Dempson JB, Jonsson B, Jonsson N, O’Connell MF, Mortensen E (2003). "Atlantic salmon Salmo salar L., brown trout Salmo trutta L. and Arctic charr Salvelinus alpinus (L.): a review of aspects of their life histories". Ecology of Freshwater Fish. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0633.2003.00010.x.

- 1 2 3 4 Heen, K. (1993). Salmon Aquaculture. Halstead Press.

- ↑ Youngson, A. F., Webb, J. H., Thompson, C. E., and Knox, D. 1993. Spawning of escaped farmed Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar): hybridization of females with brown trout (Salmo trutta). Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences, 50:1986-1990.

- ↑ Matthews, M. A., Poole, W. R., Thompson, C. E., McKillen, J., Ferguson, A., Hindar, K., and Wheelan, K. F. 2000. Incidence of hybridization between Atlantic salmon, Salmo salar L., and brown trout, Salmo trutta L., in Ireland. Fisheries Management and Ecology, 7:337-347.

- ↑ Seawater tolerance in Atlantic salmon, Salmo salar L., brown trout, Salmo trutta L., and S. salar × S. trutta hybrids smolt. Urke HA, Koksvik J, Arnekleiv JV, Hindar K, Kroglund F, Kristensen T. Source Norwegian Institute of Water Research, 7462, Trondheim, Norway. henning.urke(@)niva.no

- ↑ Natural hybridization between Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) and brown trout (Salmo trutta) in northern Spain by Carlos Garcia de Leaniz

- 1 2 3 Sedgwick, S. (1988). Salmon Farming Handbook. Fishing News Books LTD.

- ↑ N. Bromage (1995). Broodstock Management and Egg and Larval Quality. Blackwell Science.

- 1 2 Mills, D. (1989). Ecology and Management of Atlantic Salmon. Springer-Verlag.

- ↑ R. M. J. Ginetz (May 2002). "On the Risk of Colonization by Atlantic Salmon in BC waters" (PDF). B.C. Salmon Farmers Association.

- ↑ Jenkins, J. Geraint (1974). Nets and Coracles, p. 68. London, David and Charles.

- ↑ "The River". The Penobscot River Restoration Trust. Retrieved 19 November 2013.

- ↑ Netboy, Anthony (1973) The Salmon: Their Fight for Survival, pp. 181-182. Boston, Houghton Mifflin.

- 1 2 3 Harb, M. "Upstream Battle", Canadian Geographic Magazine, June 2008, p. 24

- ↑ "Salmon campaigner lands top award". BBC News. 22 April 2007.

- ↑ "Atlantic Salmon". animallist.weebly.com. Retrieved 19 November 2013.

- ↑ Carpenter, Murray (26 December 2011). "Shiny Patches in Maine's Streambeds Are Bright Sign for Salmon". The New York Times. Retrieved February 2012. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ Fay, C., M. Bartron, S. Craig, A. Hecht, J. Pruden, R. Saunders, T. Sheehan, and J. Trial (2006). Status Review for Anadromous Atlantic Salmon (Salmo salar) in the United States. Report to the National Marine Fisheries Service and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (Report). p. 294. Retrieved July 3, 2016.

- ↑ Kendall, W. C. (1935). The fishes of New England: the salmon family. Part 2 - the salmons. Boston, Massachusetts: Memoirs of the Boston Society of Natural History: monographs on the natural history of New England. p. 90. Retrieved July 3, 2016.

- ↑ W.C. Kendall (1935). The fishes of New England- the salmon family. Part 2 - the salmons. Memoirs of the Boston Society of Natural History- monographs on the natural history of New England. 9. pp. 1–166. Retrieved July 3, 2016.

- ↑ Catherine C. Carlson (1988). GP Nicholas, ed. Where's the salmon? A reevaluation of the role of anadromous fisheries in aboriginal New England in Holocene human ecology in Northeastern North America. New York: Plenum Press. ISBN 978-0306428692.

- ↑ Catherine C. Carlson (1996). "The [In]Significance of Atlantic Salmon". History Through a Pinhole. 8(3/4 (Fall/Winter). Retrieved July 3, 2016.

- ↑ Stephen F. Jane, Keith H. Nislow, Andrew R. Whiteley (September 2014). "The use (and misuse) of archaeological salmon data to infer historical abundance in North America with a focus on New England". Reviews in Fish Biology and Fisheries. 24 (3): 943–954. doi:10.1007/s11160-013-9337-3. Retrieved July 3, 2016.

- ↑ Brian S. Robinson, George L. Jacobson, Martin G. Yates, Arthur E. Spiess, Ellen R. Cowie (October 2009). "Atlantic salmon, archaeology and climate change in New England". Journal of Archaeological Science. 36 (10): 2184–2191. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2009.06.001. Retrieved July 3, 2016.

- ↑ Robert A. Daniels and Doroty Peteet (November 1998). "Fish scale evidence for rapid post-glacial colonization of an Atlantic coastal pond". Global Ecology & Biogeography Letters. 7 (6): 467–476. doi:10.2307/2997716. Retrieved July 3, 2016.

- ↑ Atlantic Salmon Restoration Program

- ↑ Figura, David. "Cicero angler lands 27-inch Atlantic salmon in Oneida Lake". Syracuse.com. Syracuse Media Group. Retrieved 4 February 2016.

- ↑ Hladky, Gregory B. (25 Dec 2015). "Salmon Found Spawning In Farmington River Watershed For First Time in Centuries". Hartford Courant. Tribune Company. Retrieved 4 February 2016.

- ↑ Jaymi Heimbuch (March 11, 2016). "Wild Atlantic salmon are spawning in Connecticut River for the first time in 200 years". Mother Nature Network. Retrieved July 3, 2016.

- 1 2 3 P. Collen & R. J. Gibson (2001). "The general ecology of beavers (Castor spp.), as related to their influence on stream ecosystems and riparian habitats, and the subsequent effects on fish – a review" (PDF). Reviews in Fish Biology and Fisheries. 10 (4): 439–461. doi:10.1023/A:1012262217012.

- ↑ Howard Park & Øystein Cock Rønning (2007). "Low potential for restraint of anadromous salmonid reproduction by beaver Castor fiber in the Numedalslågen river catchment, Norway". River Research and Applications. 23 (7): 752–762. doi:10.1002/rra.1008.

- ↑ Barry A. Taylor, Charles MacInnis, Trevor A. Floyd (2010). "Influence of Rainfall and Beaver Dams on Upstream Movement of Spawning Atlantic Salmon in a Restored Brook in Nova Scotia, Canada". River Research and Applications: 183–193. doi:10.1002/rra.1252.

- ↑ Douglas B. Sigourney, Benjamin H. Letcher & Richard A. Cunjak (2006). "Influence of beaver activity on summer growth and condition of age-2 Atlantic salmon parr". Transactions of the American Fisheries Society. 135 (4): 1068–1075. doi:10.1577/T05-159.1.

- ↑ (16 U.S.C. 1532(19)) http://www.epa.gov/EPA-SPECIES/1998/May/Day-01/e11668.htm[]

- ↑ "Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)". Bring Back the Salmon Lake Onterio. Retrieved 17 September 2015.

- ↑ "Endangered Populations". Atlantic Salmon Federation. Retrieved 17 September 2015.

- ↑ "NASCO ~ The North Atlantic Salmon Conservation Organization". Nasco.int. Retrieved 11 February 2012.

- ↑ Greenpeace International Seafood Red list Archived 10 April 2010 at the Wayback Machine.

References

- Atlantic salmon NOAA FishWatch. Retrieved 4 November 2012.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Salmo salar. |

| External identifiers for Salmo salar | |

|---|---|

| Encyclopedia of Life | 206776 |

| ITIS | 161996 |

| NCBI | 8030 |

| WoRMS | 127186 |

| Also found in: Wikispecies, FishBase | |

- Atlantic Salmon Conservation Foundation

- NOAA Fisheries Atlantic salmon page

- Atlantic Salmon Federation

- Issues salmon face – Smithsonian Ocean Portal

- State of Maine, Atlantic Salmon Commission

- University of Massachusetts information regarding Atlantic salmon

- Atlantic salmon's page on World Wide Fund for Nature's website

- Alaska Fish and Game Atlantic salmon page

- Atlantic Salmon Trust, an organization working to protect the Atlantic salmon

- Atlantic Salmon Fishing, Information about Atlantic Salmon Fishing

- Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources, Information About Atlantic Salmon Restoration Program

- Atlantic Salmon Fishing Reports & Images

- Salmon Ireland, information on the salmon rivers

.png)