Ashvamedhika Parva

Ashvamedhika Parva (Sanskrit: अश्वमेध पर्व), or the "Book of Horse Sacrifice," is the fourteenth of eighteen books of the Indian Epic Mahabharata. It has 2 sub-books and 92 chapters.[1][2]

Ashvamedhika Parva begins with an advice from Krishna and Vyasa who recommend Yudhishthira to perform the Ashvamedhika ceremony. Yudhishthira discloses that the treasury is empty because of the war. Krishna suggests mining gold in Himavat, near mount Meru. He recites the story of king Muratta. Yudhishthira proceeds with the effort to mine gold, fill his treasury and perform the Ashvamedhika ceremony.[3]

The book includes Anugita parva, over 36 chapters, which Krishna describes as mini Bhagavad Gita. The chapters are recited because Arjuna tells Krishna that he is unable to recollect the wisdom of Bhagavad Gita in the time of peace, and would like to listen to Krishna's wisdom again. Krishna recites Anugita - literally, Subsequent Gita - as a dialogue between a Brahmin's wife and Brahma. Scholars have suggested Anugita to be a spurious addition to Ashvamedhika Parva in medieval times, and a corruption of the original Mahabharata.[4][5]

Structure and chapters

Ashvamedhika Parva (book) has 2 sub-parvas (sub-books or little books) and 92 adhyayas (sections, chapters).[2] The two sub-parvas are:

- 1. Aswamedhika parva

- 2. Anugita parva

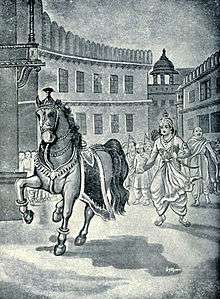

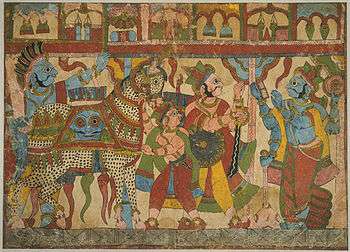

The Parva narrates the royal ceremony of the Ashvamedha initiated by Yudhishthira, after recommendations of Krishna. The ceremony is a year-long event where the horse roams any land in any direction it wishes to. The horse is followed by an army led by Arjuna, whose mission is to challenge any ruler who objects the free movement of the horse. This ceremony establishes the primacy of Yudhishthira as the emperor, and his recognition by other rulers and kingdoms. At the end of the year, victorious Arjuna's army and the horse return to the emperor's capital, and the horse is sacrificed before many kings.[2]

The Anugita sub-parva recites a restatement of Bhagavad Gita teachings by Krishna to Arjuna. However, its authenticity and origins have been questioned by scholars.[3] The various manuscripts of the Mahabharata discovered in India in early to mid 19th century, show inconsistencies in the 36 Chapters of Anugita, including the name itself. The so-called Bombay manuscripts further splits the Anugita into Anugita, Vasudevagamana, Brahma Gita, Brahmana Gita, Gurusishya samvada and Uttankopakhyana. The Madras, Calcutta and Ahmedabad manuscripts give different names. Hall suggests Anugita may have been composed and inserted into the original sometime during the 16th or 17th century AD.[6]

English translations

Aswamedhika Parva was composed in Sanskrit. Several translations of the book in English are available. Two translations from 19th century, now in public domain, are those by Kisari Mohan Ganguli[2] and Manmatha Nath Dutt.[1] The translations vary with each translator's interpretations.

Debroy, in 2011, notes[7] that updated critical edition of Ashvamedhika Parva, after removing verses and chapters generally accepted so far as spurious and inserted into the original, has 1 sub-books, 96 adhyayas (chapters) and 2,741 shlokas (verses).

Salient features

Aswamedhika Parva includes the philosophical treatise Anûgîta, as well as many tales and fables such as the mongoose at the sacrifice.

The fable of mongoose: animal sacrifice or compassion

A mongoose with blue eyes and gold colored on one side, appears during the final Aswamedhika stages of the fire yajna by Yudhishthira and other kings. The mongoose, in a thundering human voice, says, "O kings, this animal sacrifice is not equal to the tiny amount of barley by unccha vow ascetic." Yudhishthira does not understand, so asks the mongoose for an explanation. The mongoose tells them a story:[3] Long ago, there was a terrible famine. The ascetic and his family had nothing to eat. To find food, the ascetic would do what people on unccha vow do - go to fields already harvested, and like pigeons pick left over grains from the harvested field to find food.

One day, after many hours of harsh work, the ascetic finds a handful of barley grains. He brings the grains home, and his wife cooks it. Just when his son and daughter in law, his wife and he are about to eat their first meal in few days, a guest arrives. The ascetic washes the guest's feet and inquires how he was doing. The guest says he is hungry. The ascetic, explains the mongoose, gives his guest his share of cooked barley. The guest eats it, but says it was too little, he is still hungry. The wife of the ascetic hears the guest. She offers her own share of cooked barley, even though she too is starving. The guest eats that too, but said he still feels hungry. The ascetic's son and daughter-in-law give all their share of cooked barley too. The guest finishes it, then smiles and re-appears in the form of god Dharma. The god gives the family a boon and fills their home with food, saying that it is not the quantity that matters, but quality of care and love given one's circumstances. The mongoose asks if Yudhishthira is confident that his animal sacrifice would please the deity Dharma. Before Yudhishthira could answer, the mongoose disappears.[2]

The Rishis at the yajna ask if animal sacrifice is appropriate, or should they show compassion for all creatures. Some suggest that seeds of grain be substituted, and animals be set free. Listening to the discussion between the Rishis, king Vasu suggests in Ashvamedhika Parva, that large gifts from a sinful person are of no value, but even small gifts from a righteous person given with love is of great merit.[1]

Quotes and teachings

Anugita parva, Chapter 27:

In that forest,[1] Intelligence is the tree, Emancipation is the fruit, Tranquility is the shade;

It has Knowledge for its resting house, Contentment for its water, and Kshetrajna[2] for its sun.

Tranquility is praised by those who are conversant with the forest of knowledge.

- ^ (reached after Yoga and hospitality to Rishis, see the preceding verses for context; see cited K.M. Ganguli source)

- ^ awareness and knowledge of one's body (from Sanskrit: Kshetra-jna); see: Bhawuk (2010), A Perspective on Epistemology and Ontology of Indian Psychology: A Synthesis of Theory, Method and Practice; Psychology & Developing Societies, 22(1), pages 157-190

Anugita parva, Chapter 44:

Days end with the sun’s setting, and nights with the sun’s rising;

the end of pleasure is always sorrow, and the end of sorrow is always pleasure.

All associations have dissociations for their end, and life has death for its end;

All action ends in destruction, and all that is born certainly dies.

Everything is transient, everything ends;

Only of knowledge, there is no end.

See also

References

- 1 2 3 Ashvamedhika Parva The Mahabharata, Translated by Manmatha Nath Dutt (1905)

- 1 2 3 4 5 Ashvamedhika Parva The Mahabharata, Translated by Kisari Mohan Ganguli, Published by P.C. Roy (1893)

- 1 2 3 John Murdoch (1898), The Mahabharata - An English Abridgment, Christian Literature Society for India, London, pages 121-123

- ↑ Sharma, A. (1978), The Role of the Anugītā in the Understanding of the Bhagavadgītā, Religious Studies, 14(2), pages 261-267

- ↑ Anugita K.T. Telang (1882), English Translation, See Introduction

- ↑ K.T. Telang (Editor: Max Müller),The Bhagavadgîtâ: With the Sanatsugâtîya and the Anugîtâ, p. 198, at Google Books, Oxford University Press, See pages 198-212

- ↑ Bibek Debroy, The Mahabharata : Volume 3, ISBN 978-0143100157, Penguin Books, page xxiii - xxiv of Introduction

- ↑ Aswamedhika Parva The Mahabharata, Translated by Kisari Mohan Ganguli (1893), Chapter 27, page 69-70 Abridged

- ↑ Aswamedhika Parva The Mahabharata, Translated by Kisari Mohan Ganguli (1893), Chapter 44, page 110 Abridged

External links

- Ashvamedhika Parva, English Translation by Kisari Mohan Ganguli

- Ashvamedhika Parva, English Translation by Manmatha Nath Dutt

- Ashvamedhika Parva in Sanskrit by Vyasadeva with commentary by Nilakantha - Worldcat OCLC link

- Ashvamedhika Parva in Sanskrit and Hindi by Ramnarayandutt Shastri, Volume 5

- Ashvamedhika Parva English Translation by Kisari Mohan Ganguli, another archive