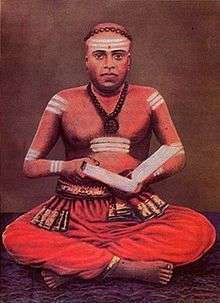

Arumuka Navalar

| Arumuka Navalar | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

Kandar Arumukam Pillai 18 December 1822 Nallur, Jaffna District, Sri Lanka |

| Died |

5 December 1879 (aged 56) Jaffna, Sri Lanka |

| Cause of death | General illness |

| Residence | Jaffna |

| Nationality | Sri Lankan |

| Other names | Srila Sri Arumuga Navalar |

| Education | Tamil Pandithar |

| Occupation | Hindu missionary |

| Known for | Hindu reformer |

| Title | Navalar |

| Religion | Hindu (Saiva) |

| Part of a series on | ||

| Hindu philosophy | ||

|---|---|---|

| ||

| Orthodox | ||

|

|

||

| Heterodox | ||

|

|

||

|

||

Arumuka Navalar (Tamil: ஆறுமுக நாவலர், āṟumuka nāvalar ?, 18 December 1822 – 5 December 1879) was one of the early revivalists of native Hindu Tamil traditions in Sri Lanka and India. He and others like him were responsible for reviving and reforming native traditions that had come under a long period of dormancy and decline during the previous 400 years of colonial rule by various European powers. A student of the Christian missionary school system who assisted in the translation of the King James Bible into Tamil, he was influential in creating a period of intense religious transformation amongst Tamils in India and Sri Lanka, preventing large-scale conversions to Protestantism.

As part of his religious revivalism, he was one of the early adaptors of modern Tamil prose, introduced Western editing techniques, and built schools (in imitation of Christian mission schools) that taught secular and Hindu religious subjects. He was a defender of Saivism (a sect of Hinduism) against Christian missionary activity and was one of the first natives to use the modern printing press to preserve the Tamil literary tradition. He published many polemical tracts in defence of Saivism, and also sought and published original palm leaf manuscripts. He also attempted to reform Saivism itself – an effort which sometimes led to the decline of popular deities and worship modes and confrontation with traditional authorities of religion. Some post-colonial authors have criticised his contributions as parochial, limited, conservative, and favouring the elite castes.

Background information

Tamil people are found natively in South India and in Sri Lanka. During the Sangam period in the early centuries of the common era, Buddhist and Jain missionary activity from North India resulted in Tamil Hindu literati defining their own cults and literature. The result was the poems of the bhakti saints, the Nayanars and Alvars. By the 12 th century CE, Saivas and Vaishnavas created a unified approach to religious literature in Tamil and Sanskrit, monastic systems, networks of temples and pilgrimage sites, public and private liturgies, and their Brahmin and non-Brahmin leadership. They institutionalised a definition of a Tamil Hindu on the basis Tamil literary culture.[1]

The mostly Vellala and Iyer Brahmin literati were Shaiva, the largest of the sects. By the 13th to 18th centuries, Shaiva theologians codified their religious traditions as Shaiva Siddhanta. Shaiva theologians did not formally include or confront Muslims and Christians in this classification but they included them along with Buddhists, Jains, and pagans. Arumuga Navalar was one of the first Tamil laymen to undertake as his life's career the intellectual and institutional response of Saivism to Christianity in Sri Lanka and India.[2]

Response to missionary activity

The 18th and 19th century Tamils in India and Sri Lanka found themselves in the midst of intrusive Protestant Missionary activity. Although Tamil Saivas opposed Roman Catholic and Protestant missions from the earliest days that they were established, literary evidence for it is not available. But by 1835 Tamils who were able to own and operate presses used them to print palm-leaf manuscripts. They also converted native literature from poetry to prose with additional commentary. Most of these activities happened in Jaffna in British Ceylon and Madras in Madras Presidency.[2]

By the time Navalar was born, Protestants from England and America had established nine mission stations in the Jaffna peninsula. Tamils in Jaffna faced a concentrated effort to convert them as opposed to Tamil in Southern India. The first known Saiva opposition to these efforts emerged in 1828 when the teachers of the American Ceylon Mission (AMC) at Vaddukoddai wanted to learn and teach the Shaiva scripture Skanda Purana in their school. This move angered local Shaivas as they interpreted it as a move by the missionaries to understand and then ridicule a religious material. Although the missionaries were able to translate and study the material, they were unable to teach it, as locals boycotted the classes.[2]

As a response, two anti-Christian poems appeared in Jaffna. The poet Muttukumara Kavirajar (1780—1851) wrote the Jnanakkummi (Song of Wisdom) and Yesumataparikaram (Abolition of the Jesus Doctrine). This was followed up by publications of polemic nature by both sides. AMC's Batticotta Seminary launched a semimonthly and bilingual periodical called The Morning Star (Tamil Utaya Tarakai). The aim of this periodical was to challenge all non-Protestants to stand up to intellectual scrutiny. The 19th century Protestants of Jaffna believed that Shaivism was evil and in the struggle God and the Devil, they intended The Morning Star to reveal the falsity of Shaivism.[2][3][4]

Biography

| Part of a series on |

| Sri Lankan Tamils |

|---|

|

Navalar, born Arumukam also spelt Arumugam (or Arumuga Pillai) in 1822, belonged to an elite Vellalas caste. He grew up in the Tamil dominated regions of Sri Lanka. His home was in the town of Nallur on the Jaffna peninsula, a strip of land (40 by 15 miles) separated from South India by the Palk Strait. The principal town Jaffna and the peninsula were predominantly Tamil Saiva in culture distinct from that of the Sinhalese Buddhists elsewhere. It was closely linked to the Saiva culture of South India.[5][6] It was also home to the Jaffna Kingdom that had patronised this culture before it was defeated by the Portuguese colonials in 1621 CE. Nallur was also the capital of the defeated kingdom.[7]

Arumugam's father Kandhar was a Tamil poet provided a foundation in Tamil literature to Arumugam Pillai.[6] His mother Sivakami was known for her devotion to supreme Saiva deity Siva. Arumugam studied the Indian classical language, Sanskrit as well as Tamil grammar. Arumugam studied English in a Christian mission run school as a day student. After his studies, he was asked to stay on at the Jaffna Central College to teach English and Tamil.[6] The missionary school principal, Peter Percival also used him to assist in the translation of the King James Bible and other Christian literature.[6] Arumugam worked with Percival from 1841–1848 during which time he formulated his ideas as to what it meant to be a modern Hindu, under the influence of a progressive, secular and ascendant Western culture based on Judeo-Christian values.[5][8]

As he immerged himself in the study of Vedas, Agamas and Puranas, Arumugam Pillai came to the awareness that Saivas needed a clearer understanding of their own religion to stem the tide of conversions. With this in mind he relinquished the job that he had with the Weslyan Mission, although Peter Percival offered him a higher salary to stay on. He also decided not to marry as he felt that it would curtail his freedom. He relinquished his patrimony and did not get any money from his four employed brothers. From then on till the end of his life, he and his projects were supported by those who believed in his cause.[9] Through his weekly sermons at Hindu temples, he also formulated a theory to purify local Tamils of all practices that did not find sanction in a written document such as Vedas and Agamas. The lecture series and its circuit continued regularly for several years and produced a Saiva revival, for an informed piety developed and grew among many Jaffna Saivas. This was a direct tactical response to confront the Protestant's bible based arguments. While he was becoming a popular preacher, he still assisted Percival to complete the translation of the Bible. When there was a conflict as to Percival's version and another competing translation, Arumugam travelled to Madras to defend Percival's version. In 1848 he founded his own school and finally parted company with Percival.[4][10]

Saiva revivalism

To confront the power of the Christian civilisation and to use the instruments of Western civilisation's knowledge to reform their religion, in September 1842 two hundred Hindu men gathered at a Siva temple monastery. The group decided to open up a school to study Vedas and Agamas. The group also decided to start a press with the help of resident Eurasian Burghers. Arumugam Pillai who was part of the organisation wrote about the meeting in The Morning Star in a sympathetic tone.[11]

While Arumugam Pillai was still working on translating the Bible, he published a seminal letter in The Morning Star under a pseudonym in September 1841. It was a comparative study of Christianity and Saivism and targeted the weakness in the argument Protestant missionaries had used against local Saiva practices. Protestant missionaries had attacked the idol worship and temple rituals of the local Saivas as devilish and of no value but Navar found evidence that Christianity and Jesus himself were rooted in the temple rituals of the ancient Israelites.[12][13] His letter admonished the missionaries for misrepresenting their own religion and concluded that in effect there was no difference between Christianity and Saivism as far as idol worship and temple rituals were concerned. Although The Morning Star editors tried to reply to the letter, the damage was done.[14]

Circuit preaching

Using the preaching methods popularised by the Methodist preachers, he became a circuit preacher. His first secession was on 31 December 1847 at Vaideeswaran Temple in Vannarpannai. It was a weekly event known as Prasangams on every Friday evening. In these secession he read from sacred texts and then preached in a manner that lay people understood. He was helped by his friend Karttikeya Aiyar of Nallur and his students from his school. The sermon topics were mostly ethical, liturgical, and theological and included the evils of adultery, drunkenness, the value of non-killing, the conduct of women, the worship of the linga, the four initiations, the importance of giving alms, of protecting cows, and the unity of God.

Conflicts with Hindus

In his weekly sermons, he attacked Christians and Hindus as well. He specifically attacked the trustees and priests of the Nallur Kandaswami Temple in his home town because they had built the temple not according to the Agamas a century ago as well as used priests who were not initiated in the Agamas. He also opposed their worship of Vel or the weapon representing the main deity as it did not have Agamic sanction.[15]

Reformed school system

The school he founded was called Saivaprakasa Vidyasala or School of Siva's splendor. The school did not follow the traditional Tamil teaching system, in which each student worked on his own pace and the teacher pupil ratio was extremely low. Although this system produced stellar experts in subject matter but took too much labour and was inefficient compared to the western system used by the Missionaries.[16] He developed his teaching methods based on the exposure he had with the Missionaries. He developed the curriculum to be able to teach 20 students at a time and included secular subject matters and English. He also wrote the basic instruction materials for different grades in Saivism.[16] Most of his teachers were friends and acquaintances who were volunteers. This school system was duplicated later in Chidambaram in India in 1865 and it still exits. But the school system he founded in Sri Lanka was replicated and over 100 primary and secondary schools were built based on his teaching methods. This school system produced numerous students who had clearer understanding of their religion, rituals and theology and still able to function in a western oriented world.[8][16]

Navalar title

As an owner of a pioneering new school with the a need for original publications in Tamil prose to teach subjects for all grades, he felt a need for a printing press. He and his colleague Sadasiva Pillai went to Madras, India in 1849 to purchase a printing press. On the way they stopped at Tiruvatuturai Ateenam in Tanjavur, India, an important Saiva monastery. He was asked by the head of the monastery to preach. After listening to his preaching and understanding his unusual mastery of the knowledge of Agamas, the head of the monastery conferred on him the title Navalar (learned). This honorary degree from a prestigious Saiva monastery enhanced his position amongst Saivas and he was known as the Navalar since then.[8]

Literary contributions

While in India he published two texts, one was an educational tool (teachers guide) Cüdãmani Nikantu, a sixteenth-century lexicon of simple verses and Saundarya Lahari, a Sanskrit poem in praise of the Primeval Mother Goddess, geared towards devotion. These were the first effort at editing and printing Tamil works for Saiva students and devotees.[17] His press was set up in a building that was donated by a merchant of Vannarpannai. It was named the Vidyaanubalana yantra sala (Preservation of Knowledge Press).[17] The initial publications included Bala Potam (Lessons for Children) in 1850 and 1851. They were graded readers, simple in style, similar in organisation to those used in the Protestant schools. This was followed up by a third volume in 1860 and 1865. It consisted of thirtynine advanced essays in clear prose, discussing subjects such as God, Saul, The Worship of God, Crimes against the Lord, Grace, Killing, Eating meat, Drinking liquor, Stealing, Adultery, Lying, Envy, Anger, and Gambling. These editions were in use 2007.[18]

Other notable texts published included The Prohibition of Killing, Manual of worship of Shiva temple and The Essence of the Saiva Religion. His first major literary publication appeared in 1851, the 272-page prose version of Sekkilar's Periya Puranam, a retelling of the twelfth century hagiography of the Nayanars or Saivite saints.[18] In 1853 he published Nakkirar's Tirumurukarrupatai, with its own commentary. It was a devotional poem to Murugan.[19] This was followed by local missionaries attacking Murugan as immoral deity for marrying two women. As a response Navalar published Radiant Wisdom explaining how the stories embody differing levels of meaning.[20] He also published literature of controversial nature. He along with Centinatha Aiyar, published examples of indecent language from the Bible and published it as Disgusting Things in the Bible (Bibiliya Kutsita). In 1852, he along with Ci. Vinayakamurtti Cettiyar of Nallur, printed the Kummi Song on Wisdom of Muttukumara Kavirajar leading to calls by local Christians to shut the printing press down.[20][21]

The seminal work that was geared towards stemming the tide of conversions was printed in 1854. It was a training manual for the use of Saivas in their opposition to the missionaries, titled The Abolition of the Abuse of Saivism (Saiva dusana parihara).[20]

A Methodist missionary, who had worked in Jaffna, described the manual thirteen years after it had appeared as:

"Displaying an intimate and astonishing acquaintance with the Holy Bible. (the author) labors cleverly to show that the opinions and ceremonies of Jehovah's ancient people closely resembled those of Shaivism, and were neither more nor less Divine in their origin and profitable in their entertainment and pursuit. The notion of merit held by the Hindus, their practices of penance, pilgrimage, and lingam-worship, their ablutions, invocations, and other observances and rites, are cunningly defended on the authority of our sacred writings! That a great effect was thus produced in favour of Sivaism and against Christianity cannot be denied".

This manual was widely used in Sri Lanka and India; it was reprinted at least twice in the nineteenth century, and eight times by 1956.[20]

Legacy and assessment

According to Prof. Dennis Hudson,[22] Navalar's contributions although began in Jaffna, spread to both in Sri Lanka as well as Southern India, thus establishing two centres of reform. He had two schools, two presses and pressed on against Christian missionary activity on both sides as well as against Hindus whom he thought were unorthodox. He produced approximately ninety-seven Tamil publications, twenty three were his own creations, eleven were commentaries, and forty were his editions of those works of grammar, literature, liturgy, and theology that were not previously available in print. With this recovery, editing, and publishing of ancient works, Navalar laid the foundations for the recovery of lost Tamil classics that his successors such as U. V. Swaminatha Iyer and C.W. Thamotharampillai continued.[8] He was the first person to deploy the prose style in the Tamil language and according to Tamil scholar Kamil Zvelebil in style it bridged the medieval to the modern.[23]

Navalar established the world's first Hindu school adapted to the modern needs that succeeded and flourished. While the school he established in Chidamharam in 1865 has survived to this day, similar schools seem to have spread only to two nearby towns. In Sri Lanka, eventually more than one hundred and fifty primary and secondary schools emerged from his work.[16] Many of the students of these schools were successful in defending the Saiva culture not only against Christian missionary activities but also against neo-Hindu sects.[16] His reforms and contributions were added to by scholars such as V. Kalyanasundaram (1883—1953), and Maraimalai Adigal (1876–1950), who developed their own schools of theology within the Saiva heritage.[16] Although it is difficult to quantify as to how many Hindus may have converted to Protestant Christianity without his intervention but according to Bishop Sabapathy Kulendran, the low rate of conversion compared to the initial promise was due to Navalar's activities.[24]

Arumuka Navalar who identified himself with an idealised past, worked within the traditions of Saiva culture and strictly adhered what was available in the Saiva doctrine.[1][25] He was an unapologetic defender of Savisim and the resultant class and caste privileges enjoyed by the higher castes. Although he never identified him as a Vellala, his efforts led to Saiva Vellala caste consolidation of traditional privileges' and prevention of the emergence of converted Christian Vellala and Saiva and Christian Karaiyar elites.[26][26][27] Although Navalar did not exhibit any Tamil oriented political awareness or pan ethnic Tamil consciousness as opposed to a Saiva and a defender of traditional privilege,[28] in Sri Lanka and South India, his aggressive preaching of a Saiva cultural heritage contributed to the growth Tamil nationalism.[29] The Tamil nationalist movement had an element that Saiva Siddhanta preceded all others as the original Tamil religion.[24] Navalar's insistence on the Agamas as the criteria of Saiva worship, moreover, gave momentum to the tendency among Tamils everywhere to attempt to subsume local deities under the Agamic pantheon and to abandon animal sacrifice altogether.[30]

Arumuga Navalar's reforms are seen by some as too conservative and is overly conforming to principles of Sanskritization and caste hegemony.[31] His affirmation of casteist ideology was officially unacceptable to secular nationalisms, of both India and Sri Lanka.[4][32][33] Even within the various schools of Hinduism, Navalar worked vigorously to marginalise the popular Virasaiva traditions of Jaffna along with Vaishnavism and the popular folk religion.[34] Although Navalar made important contributions towards locating and publishing Palm leaf originals of ancient and medieval Tamil literature, according to Karthigesu Sivathamby, Navalar deliberately minimised the impact of secular literature amongst Tamils to enhance the position of Saiva religious literature.[35] His legacy still provokes negative reactions from the politically Left oriented Tamil intellectuals, Virasaivas, Dalits amongst Tamil Hindus and activist Christians.[36]

Notes

- 1 2 Jones & Hudson 1992, pp. 27.

- 1 2 3 4 Jones & Hudson 1992, pp. 28

- ↑ Jones & Hudson 1992, pp. 30

- 1 2 3 Gupta, Basu & Chatterjee 2010, pp. 165

- 1 2 Jones & Hudson 1992, pp. 29

- 1 2 3 4 Kaplan & Hudson 1994, pp. 97

- ↑ Sabaratnam 2010

- 1 2 3 4 Zvelebil 1991, pp. 155

- ↑ Jones & Hudson 1992, pp. 36–38

- ↑ Jones & Hudson 1992, pp. 36

- ↑ Jones & Hudson 1992, pp. 33

- ↑ Goodman & Hudson 1994, pp. 56

- ↑ Sugirtharajah 2005, pp. 6

- ↑ Jones & Hudson 1992, pp. 33–35

- ↑ Kaplan & Hudson 1994, pp. 100

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Jones & Hudson 1992, pp. 48

- 1 2 Jones & Hudson 1992, pp. 41

- 1 2 Jones & Hudson 1992, pp. 42

- ↑ Zvelebil 1991, pp. 156

- 1 2 3 4 Kaplan & Hudson 1994, pp. 105–106

- ↑ Jones & Hudson 1992, pp. 44

- ↑ Prof. D. Dennis Hudson (1939–2007) was a Professor of World Religions at the Department of Religion, Smith College at SUNY. He taught religious history of India and South Asian religious literature in translation. His research interests focused on the Tamil speaking peoples of South Asia from their earliest appearance to the present, with special attention to two period: the 8th–9th century period of Alvar and Nayanar and the 18th–19th century period of interaction between Christians, Hindus, and Muslims, notably between the Protestants and Hindus. His detailed study of Arumuka Navalar is an attempt at understanding the Tamil Hindu reaction to an intrusive Protestant worldview in the 18–19th century period.

- ↑ Zvelebil 1991, pp. 153–157

- 1 2 Jones & Hudson 1992, pp. 49

- ↑ Schalk 2010, pp. 116

- 1 2 Schalk 2010, pp. 120

- ↑ Wilson 1999, pp. 20

- ↑ Schalk 2010, pp. 121

- ↑ Balachandran, P.K. (24 June 2006). "Cutting edge of Hindu revivalism in Jaffna". Daily News. Lake House Publishing. Retrieved 20 September 2011.

- ↑ Hellmann-Rajanayagam 1989, pp. 235–254

- ↑ Wilson 1999, pp. 53–54

- ↑ Wikremasinghe 2006, pp. 83

- ↑ "Saiva revivalist Arumuga Navalar remembered on 181st birthday". Tamilnet. Retrieved 20 September 2011.

- ↑ Schalk 2010, pp. 119

- ↑ Gupta, Basu & Chatterjee 2010, pp. 166

- ↑ Schalk 2010, pp. 119–120

Cited literature

- Goodman, Hananya; Hudson, D. Dennis (1994). Between Jerusalem and Benares:Comparative Studies in Judaism and Hinduism. SUNY. ISBN 0-7914-1716-6.

- Gupta, Suman; Basu, Tapan; Chatterjee, Subarno (2010). Globalization in India: Contents and Discontents. Dorling Kindersley. ISBN 978-81-317-1988-6.

- Hellmann-Rajanayagam, Dagmar (1989). "Arumuka Navalar: Religious reformer or national leader of Eelam". Indian Economic Social History Review. 26: 235–257. doi:10.1177/001946468902600204.

- Jones, Kenneth W.; Hudson, D. Dennis (1992). Religious controversy in British India: dialogues in South Asian languages. SUNY. ISBN 0-7914-0828-0.

- Kaplan, Stephen; Hudson, D. Dennis (1994). Indigenous Responses to Western Christianity. NYU Press. ISBN 0-8147-4649-7.

- Sabaratnam, T (2010). Sri Lankan Tamil Struggle. The Sangam.

- Schalk, Peter (2010). Michael Bergunder, Heiko Frese and Ulrike Schroder, ed. Ritual, Caste and religion on Colonial South India -Sustaining the pre-colonial paste:Saiva defiance against Christian rule in the 19th century Jaffna. Franckesche Stifungen zu Halle, Halle. ISBN 978-3-447-06377-7.

- Sugirtharajah, Rasiah (2005). The Bible and empire: postcolonial explorations. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-82493-1.

- Zvelebil, Kamil (1991). Companion studies to the history of Tamil literature. Brill Academic Publishers. ISBN 90-04-09365-6.

- Wikremasinghe, Nira (2006). Sri Lanka in the Modern Age: A History of Contested Identities. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 0-8248-3016-4.

- Wilson, A.J. (1999). Sri Lankan Tamil Nationalism. UBC. ISBN 0-7748-0759-8.

Further reading

- Ambalavanar, Devadarshan Niranjan (2006). "Arumuga Navalar and the construction of a Caiva public in colonial Jaffna (Sri Lanka, India)". Harvard University. Retrieved 20 September 2011.

- Pfaffenberger, Bryan (1982), Caste in Tamil culture:The Religious foundations of Sudra domination in Tamil Sri Lanka, Syracuse University, ISBN 0-915984-84-9

- Rajesh (2003). "Research Theme: Mapping the processes of transmission, recovery and reception of classical Tamil literature in late 19th and early 20th century colonial Madras Presidency" (.pdf). Insititute Francais de Pondicherry (Department of Indology). Retrieved 18 October 2007.

- Young, Richard; Jebanesan, S (1995). The Bible trembled : the Hindu-Christian controversies of nineteenth-century Ceylon. Vienna Inst. für Indologie. ISBN 3-900271-27-5.

External links

- Arumuka Navalar, a contemporary Christian Missionary perspective

- Arumuka Navalar, a Hindu perspective