Arsenal F.C.

| ||||

| Full name | Arsenal Football Club | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nickname(s) | The Gunners | |||

| Founded | 1886 as Dial Square[1] | |||

| Ground | Emirates Stadium | |||

| Capacity | 60,432[2] | |||

| Owner | Arsenal Holdings plc | |||

| Chairman | Sir Chips Keswick | |||

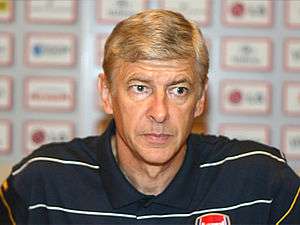

| Manager | Arsène Wenger | |||

| League | Premier League | |||

| 2015–16 | Premier League, 2nd | |||

| Website | Club home page | |||

|

| ||||

Arsenal Football Club is an English professional football club based in Highbury, London, that plays in the Premier League, the top flight of English football. The club has won 12 FA Cups, a joint-record, 13 League titles, two League Cups, 14 FA Community Shields, one UEFA Cup Winners' Cup and one Inter-Cities Fairs Cup.

Arsenal was the first club from the South of England to join The Football League, in 1893. They entered the First Division in 1904, and have since accumulated the second most points.[3] Relegated only once, in 1913, they continue the longest streak in the top division.[4] In the 1930s, Arsenal won five League Championships and two FA Cups, and another FA Cup and two Championships after the war. In 1970–71, they won their first League and FA Cup Double. Between 1989 and 2005, they won five League titles and five FA Cups, including two more Doubles. They completed the 20th century with the highest average league position.[5]

Herbert Chapman won Arsenal's first national trophies, but died prematurely. The WM formation, floodlights, and shirt numbers have all been attributed to him.[6] He added the white sleeves and brighter red to Arsenal's kit. Arsène Wenger has been the longest-serving manager and has won the most trophies. His teams set several English records: the longest win streak; the longest unbeaten run; and the only 38 match season unbeaten.

In 1886, Woolwich munitions workers founded the club as Dial Square. In 1913, the club crossed the city to Arsenal Stadium in Highbury. They became Tottenham Hotspur's nearest club, commencing the North London derby. In 2006, they moved down the road to the Emirates Stadium. Arsenal earned €435.5m in 2014–15, with the Emirates Stadium generating the highest revenue in world football.[7] Based on social media activity from 2014–15, Arsenal's fanbase is the fifth largest in the world.[7] In 2016, Forbes estimated the club was the second most valuable in England, worth $2.0 billion.[8]

History

1886–1919: Changing names

On 1 December 1886, munitions workers in Woolwich, now South East London, formed Arsenal as Dial Square, with David Danskin as their first captain.[9] Named after the heart of the Royal Arsenal complex, they took the name of the whole complex a month later.[10][11] Royal Arsenal F.C.'s first home was Plumstead Common,[11] though they spent most of their time in South East London playing on the other side of Plumstead, at the Manor Ground. Royal Arsenal won Arsenal's first trophies in 1890 and 1891, and these were the only football association trophies Arsenal won during their time in South East London.[12][13]

Royal Arsenal renamed themselves for a second time upon becoming a limited liability company in 1893. They registered their new name, Woolwich Arsenal, with The Football League when the club ascended later that year.[14][15] Woolwich Arsenal was the first southern member of The Football League, starting out in the Second Division and winning promotion to the First Division in 1904. Falling attendances, due to financial difficulties among the munitions workers and the arrival of more accessible football clubs elsewhere in the city, led the club close to bankruptcy by 1910.[16][17] Businessmen Henry Norris and William Hall took the club over, and sought to move them elsewhere.

In 1913, soon after relegation back to the Second Division, Woolwich Arsenal moved to the new Arsenal Stadium in Highbury, North London. This saw their third change of name: the following year, they reduced Woolwich Arsenal to simply The Arsenal.[18][19] In 1919, The Football League voted to promote The Arsenal, instead of relegated local rivals Tottenham Hotspur, into the newly enlarged First Division, despite only listing the club sixth in the Second Division's last pre-war season of 1914–15. Some books have speculated that the club won this election to division one by dubious means.[20] Later that year, The Arsenal started dropping "The" in official documents, gradually shifting its name for the final time towards Arsenal, as it is generally known today.[21]

1919–1953: The Bank of England Club

With a new home and First Division football, attendances were more than double those at the Manor Ground, and Arsenal's budget grew rapidly.[22][23] Their location and record-breaking salary offer lured star Huddersfield Town manager Herbert Chapman in 1925.[24][25] Over the next five years, Chapman built a new Arsenal. He appointed enduring new trainer Tom Whittaker,[26] implemented Charlie Buchan's new twist on the nascent WM formation,[27][28] captured young players like Cliff Bastin and Eddie Hapgood, and lavished Highbury's income on stars like David Jack and Alex James. With record-breaking spending and gate receipts, Arsenal quickly became known as the Bank of England club.[29][30]

Transformed, Chapman's Arsenal claimed their first national trophy, the FA Cup, in 1930. Two League Championships followed, in 1930–31 and 1932–33.[31] Chapman also presided over multiple off the pitch changes: white sleeves and shirt numbers were added to the kit;[32] a Tube station was named after the club;[33][34] and the first of two opulent, Art Deco stands was completed, with some of the first floodlights in English football.[23] Suddenly, in the middle of the 1933–34 season, Chapman died of pneumonia.[35] His work was left to Joe Shaw and George Allison, who saw out a hat-trick with the 1933–34 and 1934–35 titles, and then won the 1936 FA Cup and 1937–38 title.

World War II meant The Football League was suspended for seven years, but Arsenal returned to win it in the second post-war season, 1947–48. This was Tom Whittaker's first season as manager, after his promotion to succeed Allison, and the club had equalled the champions of England record. They won a third FA Cup in 1950, and then won a record-breaking seventh championship in 1952–53.[36] However, the war had taken its toll on Arsenal. The club had had more players killed than any top flight club,[37] and debt from reconstructing the North Bank Stand bled Arsenal's resources.[23][19]

1953–1986: The long sleep, Mee and Neill

Arsenal were not to win the League or the FA Cup for another 18 years. The '53 Champions squad was old, and the club failed to attract strong enough replacements.[38] Although Arsenal were competitive during these years, their fortunes had waned; the club spent most of the 1950s and 1960s in midleague mediocrity.[39] Even former England captain Billy Wright could not bring the club any success as manager, in a stint between 1962 and 1966.[40]

Arsenal tentatively appointed club physiotherapist Bertie Mee as acting manager in 1966.[41][42] With new assistant Don Howe and new players such as Bob McNab and George Graham, Mee led Arsenal to their first League Cup finals, in 1967–68 and 1968–69. Next season saw a breakthrough: Arsenal's first competitive European trophy, the 1969–70 Inter-Cities Fairs Cup. And the season after, an even greater triumph: Arsenal's first League and FA Cup double, and a new champions of England record.[43] This marked a premature high point of the decade; the Double-winning side was soon broken up and the rest of the decade was characterised by a series of near misses, starting with Arsenal finishing as FA Cup runners up in 1972, and First Division runners-up in 1972–73.[42]

Former player Terry Neill succeeded Mee in 1976. At the age of 34, he became the youngest Arsenal manager to date.[44] With new signings like Malcolm Macdonald and Pat Jennings, and a crop of talent in the side such as Liam Brady and Frank Stapleton, the club reached a trio of FA Cup finals (1978, 1979 and 1980), and lost the 1980 European Cup Winners' Cup Final on penalties. The club's only trophy during this time was a last-minute 3–2 victory over Manchester United in the 1979 FA Cup Final, widely regarded as a classic.[45][46]

1986–present: Graham to Wenger

One of Bertie Mee's double winners, George Graham, returned as manager in 1986. Arsenal won their first League Cup in 1987, Graham's first season in charge. By 1988, new signings Nigel Winterburn, Lee Dixon and Steve Bould had joined the club to complete the "famous Back Four" led by existing player Tony Adams.[47] They immediately won the 1988–89 Football League, snatched with a last-minute goal in the final game of the season against fellow title challengers Liverpool.[48] Graham's Arsenal won another title in 1990–91, losing only one match, won the FA Cup and League Cup double in 1993, and the European Cup Winners' Cup, in 1994. Graham's reputation was tarnished when he was found to have taken kickbacks from agent Rune Hauge for signing certain players,[49] and he was dismissed in 1995. His permanent replacement, Bruce Rioch, lasted for only one season, leaving the club after a dispute with the board of directors.[50]

The club metamorphosed during the long tenure of manager Arsène Wenger, appointed in 1996. New, attacking football,[51] an overhaul of dietary and fitness practices,[52] and efficiency with money[53] have defined his reign. Accumulating key players from Wenger's homeland, such as Patrick Vieira and Thierry Henry, Arsenal won a second League and Cup double in 1997–98 and a third in 2001–02. In addition, the club reached the final of the 1999–2000 UEFA Cup, were victorious in the 2003 and 2005 FA Cups, and won the Premier League in 2003–04 without losing a single match, an achievement which earned the side the nickname "The Invincibles".[54] This latter feat came within a run of 49 league matches unbeaten from 7 May 2003 to 24 October 2004, a national record.[55]

Arsenal finished in either first or second place in the league in eight of Wenger's first nine seasons at the club, although on no occasion were they able to retain the title.[56] The club had never progressed beyond the quarter-finals of the Champions League until 2005–06; in that season they became the first club from London in the competition's fifty-year history to reach the final, in which they were beaten 2–1 by Barcelona.[57] In July 2006, they moved into the Emirates Stadium, after 93 years at Highbury.[58] Arsenal reached the final of the 2007 and 2011 League Cups, losing 2–1 to Chelsea and Birmingham City respectively.

The club had not gained a major trophy since the 2005 FA Cup until 17 May 2014, when Arsenal beat Hull City in the 2014 FA Cup Final, coming back from a 2–0 deficit to win the match 3–2.[59] This qualified them for the 2014 FA Community Shield where they would play Premier League champions Manchester City. They recorded a resounding 3–0 win in the game, winning their second trophy in three months.[60] Nine months after their Community Shield triumph, Arsenal appeared in the FA Cup final for the second year in a row, thrashing Aston Villa 4–0 in the final and becoming the most successful club in the tournament's history with 12 titles.[61] On 2 August 2015, Arsenal beat Chelsea 1–0 at Wembley Stadium to retain the Community Shield and earn their 14th Community Shield title.[62]

Crest

Unveiled in 1888, Royal Arsenal's first crest featured three cannons viewed from above, pointing northwards, similar to the coat of arms of the Metropolitan Borough of Woolwich (nowadays transferred to the coat of arms of the Royal Borough of Greenwich). These can sometimes be mistaken for chimneys, but the presence of a carved lion's head and a cascabel on each are clear indicators that they are cannons.[63] This was dropped after the move to Highbury in 1913, only to be reinstated in 1922, when the club adopted a crest featuring a single cannon, pointing eastwards, with the club's nickname, The Gunners, inscribed alongside it; this crest only lasted until 1925, when the cannon was reversed to point westward and its barrel slimmed down.[63]

In 1949, the club unveiled a modernised crest featuring the same style of cannon below the club's name, set in blackletter, and above the coat of arms of the Metropolitan Borough of Islington and a scroll inscribed with the club's newly adopted Latin motto, Victoria Concordia Crescit - "victory comes from harmony" – coined by the club's programme editor Harry Homer.[63] For the first time, the crest was rendered in colour, which varied slightly over the crest's lifespan, finally becoming red, gold and green. Because of the numerous revisions of the crest, Arsenal were unable to copyright it. Although the club had managed to register the crest as a trademark, and had fought (and eventually won) a long legal battle with a local street trader who sold "unofficial" Arsenal merchandise,[64] Arsenal eventually sought a more comprehensive legal protection. Therefore, in 2002 they introduced a new crest featuring more modern curved lines and a simplified style, which was copyrightable.[65] The cannon once again faces east and the club's name is written in a sans-serif typeface above the cannon. Green was replaced by dark blue. The new crest was criticised by some supporters; the Arsenal Independent Supporters' Association claimed that the club had ignored much of Arsenal's history and tradition with such a radical modern design, and that fans had not been properly consulted on the issue.[66]

Until the 1960s, a badge was worn on the playing shirt only for high-profile matches such as FA Cup finals, usually in the form of a monogram of the club's initials in red on a white background.[67]

The monogram theme was developed into an Art Deco-style badge on which the letters A and C framed a football rather than the letter F, the whole set within a hexagonal border. This early example of a corporate logo, introduced as part of Herbert Chapman's rebranding of the club in the 1930s, was used not only on Cup Final shirts but as a design feature throughout Highbury Stadium, including above the main entrance and inlaid in the floors.[68] From 1967, a white cannon was regularly worn on the shirts, until replaced by the club crest, sometimes with the addition of the nickname "The Gunners", in the 1990s.[67]

In the 2011–12 season, Arsenal celebrated their 125th year anniversary. The celebrations included a modified version of the current crest worn on their jerseys for the season. The crest was all white, surrounded by 15 oak leaves to the right and 15 laurel leaves to the left. The oak leaves represent the 15 founding members of the club who met at the Royal Oak pub. The 15 laurel leaves represent the design detail on the six pence pieces paid by the founding fathers to establish the club. The laurel leaves also represent strength. To complete the crest, 1886 and 2011 are shown on either sides of the motto "Forward" at the bottom of the crest.[69]

Colours

For much of Arsenal's history, their home colours have been bright red shirts with white sleeves and white shorts, though this has not always been the case. The choice of red is in recognition of a charitable donation from Nottingham Forest, soon after Arsenal's foundation in 1886. Two of Dial Square's founding members, Fred Beardsley and Morris Bates, were former Forest players who had moved to Woolwich for work. As they put together the first team in the area, no kit could be found, so Beardsley and Bates wrote home for help and received a set of kit and a ball.[70] The shirt was redcurrant, a dark shade of red, and was worn with white shorts and socks with blue and white hoops.[71][72]

In 1933, Herbert Chapman, wanting his players to be more distinctly dressed, updated the kit, adding white sleeves and changing the shade to a brighter pillar box red. Two possibilities have been suggested for the origin of the white sleeves. One story reports that Chapman noticed a supporter in the stands wearing a red sleeveless sweater over a white shirt; another was that he was inspired by a similar outfit worn by the cartoonist Tom Webster, with whom Chapman played golf.[73] Regardless of which story is true, the red and white shirts have come to define Arsenal and the team have worn the combination ever since, aside from two seasons. The first was 1966–67, when Arsenal wore all-red shirts;[72] this proved unpopular and the white sleeves returned the following season. The second was 2005–06, the last season that Arsenal played at Highbury, when the team wore commemorative redcurrant shirts similar to those worn in 1913, their first season in the stadium; the club reverted to their normal colours at the start of the next season.[73] In the 2008–09 season, Arsenal replaced the traditional all-white sleeves with red sleeves with a broad white stripe.[72]

Arsenal's home colours have been the inspiration for at least three other clubs. In 1909, Sparta Prague adopted a dark red kit like the one Arsenal wore at the time;[73] in 1938, Hibernian adopted the design of the Arsenal shirt sleeves in their own green and white strip.[74] In 1920, Sporting Clube de Braga's manager returned from a game at Highbury and changed his team's green kit to a duplicate of Arsenal's red with white sleeves and shorts, giving rise to the team's nickname of Os Arsenalistas.[75] These teams still wear those designs to this day.

For many years Arsenal's away colours were white shirts and either black or white shorts. In the 1969–70 season, Arsenal introduced an away kit of yellow shirts with blue shorts. This kit was worn in the 1971 FA Cup Final as Arsenal beat Liverpool to secure the double for the first time in their history.[76] Arsenal reached the FA Cup final again the following year wearing the red and white home strip and were beaten by Leeds United. Arsenal then competed in three consecutive FA Cup finals between 1978 and 1980 wearing their "lucky" yellow and blue strip,[76] which remained the club's away strip until the release of a green and navy away kit in 1982–83. The following season, Arsenal returned to the yellow and blue scheme, albeit with a darker shade of blue than before.

When Nike took over from Adidas as Arsenal's kit provider in 1994, Arsenal's away colours were again changed to two-tone blue shirts and shorts. Since the advent of the lucrative replica kit market, the away kits have been changed regularly, with Arsenal usually releasing both away and third choice kits. During this period the designs have been either all blue designs, or variations on the traditional yellow and blue, such as the metallic gold and navy strip used in the 2001–02 season, the yellow and dark grey used from 2005 to 2007, and the yellow and maroon of 2010 to 2013.[77] As of 2009, the away kit is changed every season, and the outgoing away kit becomes the third-choice kit if a new home kit is being introduced in the same year.[78]

Kit manufacturers and shirt sponsors

Arsenal's shirts have been made by manufacturers including Bukta (from the 1930s until the early 1970s), Umbro (from the 1970s until 1986), Adidas (1986–1994), Nike (1994–2014), and Puma (from 2014).[79] Like those of most other major football clubs, Arsenal's shirts have featured sponsors' logos since the 1980s; sponsors include JVC (1982–1999), Sega (1999–2002), O2 (2002–2006), and Emirates (from 2006).[72][73]

Stadiums

For most of their time in south-east London, Arsenal played at the Manor Ground in Plumstead, apart from a three-year period at the nearby Invicta Ground between 1890 and 1893. The Manor Ground was initially just a field, until the club installed stands and terracing for their first Football League match in September 1893. They played their home games there for the next twenty years (with two exceptions in the 1894–95 season), until the move to north London in 1913.[80][81]

Widely referred to as Highbury, Arsenal Stadium was the club's home from September 1913 until May 2006. The original stadium was designed by the renowned football architect Archibald Leitch, and had a design common to many football grounds in the UK at the time, with a single covered stand and three open-air banks of terracing.[23] The entire stadium was given a massive overhaul in the 1930s: new Art Deco West and East stands were constructed, opening in 1932 and 1936 respectively, and a roof was added to the North Bank terrace, which was bombed during the Second World War and not restored until 1954.[23]

Highbury could hold more than 60,000 spectators at its peak, and had a capacity of 57,000 until the early 1990s. The Taylor Report and Premier League regulations obliged Arsenal to convert Highbury to an all-seater stadium in time for the 1993–94 season, thus reducing the capacity to 38,419 seated spectators.[82] This capacity had to be reduced further during Champions League matches to accommodate additional advertising boards, so much so that for two seasons, from 1998 to 2000, Arsenal played Champions League home matches at Wembley, which could house more than 70,000 spectators.[83]

Expansion of Highbury was restricted because the East Stand had been designated as a Grade II listed building and the other three stands were close to residential properties.[23] These limitations prevented the club from maximising matchday revenue during the 1990s and first decade of the 21st century, putting them in danger of being left behind in the football boom of that time.[84] After considering various options, in 2000 Arsenal proposed building a new 60,361-capacity stadium at Ashburton Grove, since named the Emirates Stadium, about 500 metres south-west of Highbury.[85] The project was initially delayed by red tape and rising costs,[86] and construction was completed in July 2006, in time for the start of the 2006–07 season.[87] The stadium was named after its sponsors, the airline company Emirates, with whom the club signed the largest sponsorship deal in English football history, worth around £100 million.[88] Some fans referred to the ground as Ashburton Grove, or the Grove, as they did not agree with corporate sponsorship of stadium names.[89] The stadium will be officially known as Emirates Stadium until at least 2028, and the airline will be the club's shirt sponsor until the end of the 2018–19 season.[90] From the start of the 2010–11 season on, the stands of the stadium have been officially known as North Bank, East Stand, West Stand and Clock end.[91]

Arsenal's players train at the Shenley Training Centre in Hertfordshire, a purpose-built facility which opened in 1999.[92] Before that the club used facilities on a nearby site owned by the University College of London Students' Union. Until 1961 they had trained at Highbury.[93] Arsenal's Academy under-18 teams play their home matches at Shenley, while the reserves play their games at Meadow Park,[94] which is also the home of Boreham Wood F.C..

Supporters

Arsenal fans often refer to themselves as "Gooners", the name derived from the team's nickname, "The Gunners". The fanbase is large and generally loyal, and virtually all home matches sell out; in 2007–08 Arsenal had the second-highest average League attendance for an English club (60,070, which was 99.5% of available capacity),[95] and, as of 2015, the third-highest all-time average attendance.[96] Arsenal have the seventh highest average attendance of European football clubs only behind Borussia Dortmund, FC Barcelona, Manchester United, Real Madrid, Bayern Munich, and Schalke.[97][98][99][100] The club's location, adjoining wealthy areas such as Canonbury and Barnsbury, mixed areas such as Islington, Holloway, Highbury, and the adjacent London Borough of Camden, and largely working-class areas such as Finsbury Park and Stoke Newington, has meant that Arsenal's supporters have come from a variety of social classes.

.jpg)

Like all major English football clubs, Arsenal have a number of domestic supporters' clubs, including the Arsenal Football Supporters' Club, which works closely with the club, and the Arsenal Independent Supporters' Association, which maintains a more independent line. The Arsenal Supporters' Trust promotes greater participation in ownership of the club by fans. The club's supporters also publish fanzines such as The Gooner, Gunflash and the satirical Up The Arse!. In addition to the usual English football chants, supporters sing "One-Nil to the Arsenal" (to the tune of "Go West").

There have always been Arsenal supporters outside London, and since the advent of satellite television, a supporter's attachment to a football club has become less dependent on geography. Consequently, Arsenal have a significant number of fans from beyond London and all over the world; in 2007, 24 UK, 37 Irish and 49 other overseas supporters clubs were affiliated with the club.[101] A 2011 report by SPORT+MARKT estimated Arsenal's global fanbase at 113 million.[102] The club's social media activity was the fifth highest in world football during the 2014–15 season.[7]

Arsenal's longest-running and deepest rivalry is with their nearest major neighbours, Tottenham Hotspur; matches between the two are referred to as North London derbies.[103] Other rivalries within London include those with Chelsea, Fulham and West Ham United. In addition, Arsenal and Manchester United developed a strong on-pitch rivalry in the late 1980s, which intensified in recent years when both clubs were competing for the Premier League title[104] – so much so that a 2003 online poll by the Football Fans Census listed Manchester United as Arsenal's biggest rivals, followed by Tottenham and Chelsea.[105] A 2008 poll listed the Tottenham rivalry as more important.[106]

Ownership and finances

The largest shareholder on the Arsenal board is American sports tycoon Stan Kroenke.[107] Kroenke first launched a bid for the club in April 2007,[108] and faced competition for shares from Red and White Securities, which acquired its first shares off David Dein in August 2007.[109] Red & White Securities was co-owned by Russian billionaire Alisher Usmanov and Iranian London-based financier Farhad Moshiri, though Usmanov bought Moshiri's stake in 2016.[110] Kroenke came close to the 30% takeover threshold in November 2009, when he increased his holding to 18,594 shares (29.9%).[111][112] In April 2011, Kroenke achieved a full takeover by purchasing the shareholdings of Nina Bracewell-Smith and Danny Fiszman, taking his shareholding to 62.89%.[113][114] As of June 2015, Kroenke owns 41,698 shares (67.02%) and Red & White Securities own 18,695 shares (30.04%).[107] Ivan Gazidis has been the club's Chief Executive since 2009.[107]

Arsenal's parent company, Arsenal Holdings plc, operates as a non-quoted public limited company, whose ownership is considerably different from that of other football clubs. Only 62,217 shares in Arsenal have been issued,[115][116] and they are not traded on a public exchange such as the FTSE or AIM; instead, they are traded relatively infrequently on the ICAP Securities and Derivatives Exchange, a specialist market. On 10 March 2016, a single share in Arsenal had a mid price of £15,670, which sets the club's market capitalisation value at approximately £975m.[117] Most football clubs aren't listed on an exchange, which makes direct comparisons of their values difficult. Consultants Brand Finance valued the club's brand and intangible assets at $703m in 2015, and consider Arsenal an AAA global brand.[118] Business magazine Forbes valued Arsenal as a whole at $2.0 billion (£1.4 billion) in 2016, ranked second in English football.[8] Research by the Henley Business School also ranked Arsenal second in English football, modelling the club's value at £1.118 billion in 2015.[119][120]

Arsenal's financial results for the 2014–15 season show group revenue of £344.5m, with a profit before tax of £24.7m.[121] The footballing core of the business showed a revenue of £329.3m. The Deloitte Football Money League is a publication that homogenizes and compares clubs' annual revenue. They put Arsenal's footballing revenue at £331.3m (€435.5m), ranking Arsenal seventh among world football clubs.[7] Arsenal and Deloitte both list the match day revenue generated by the Emirates Stadium as £100.4m, more than any other football stadium in the world.

In popular culture

Arsenal have appeared in a number of media "firsts". On 22 January 1927, their match at Highbury against Sheffield United was the first English League match to be broadcast live on radio.[122][123] A decade later, on 16 September 1937, an exhibition match between Arsenal's first team and the reserves was the first football match in the world to be televised live.[122][124] Arsenal also featured in the first edition of the BBC's Match of the Day, which screened highlights of their match against Liverpool at Anfield on 22 August 1964.[122][125] BSkyB's coverage of Arsenal's January 2010 match against Manchester United was the first live public broadcast of a sports event on 3D television.[122][126]

As one of the most successful teams in the country, Arsenal have often featured when football is depicted in the arts in Britain. They formed the backdrop to one of the earliest football-related films, The Arsenal Stadium Mystery (1939).[127] The film centres on a friendly match between Arsenal and an amateur side, one of whose players is poisoned while playing. Many Arsenal players appeared as themselves and manager George Allison was given a speaking part.[128] More recently, the book Fever Pitch by Nick Hornby was an autobiographical account of Hornby's life and relationship with football and Arsenal in particular. Published in 1992, it formed part of the revival and rehabilitation of football in British society during the 1990s.[129] The book was twice adapted for the cinema – the 1997 British film focuses on Arsenal's 1988–89 title win,[130] and a 2005 American version features a fan of baseball's Boston Red Sox;[131] coincidentally the ending was re-made to feature the 2004–05 season that ended in a similar fashion.

Arsenal have often been stereotyped as a defensive and "boring" side, especially during the 1970s and 1980s;[132][133] many comedians, such as Eric Morecambe, made jokes about this at the team's expense. The theme was repeated in the 1997 film The Full Monty, in a scene where the lead actors move in a line and raise their hands, deliberately mimicking the Arsenal defence's offside trap, in an attempt to co-ordinate their striptease routine.[128] Another film reference to the club's defence comes in the film Plunkett & Macleane, in which two characters are named Dixon and Winterburn after Arsenal's long-serving full backs – the right-sided Lee Dixon and the left-sided Nigel Winterburn.[128]

The 1991 television comedy sketch show Harry Enfield & Chums featured a sketch from the characters Mr Cholmondly-Warner and Grayson where the Arsenal team of 1933, featuring exaggerated parodies of fictitious amateur players take on the Liverpool team of 1991.[134] In the 2007 movie, Goal II: Living the Dream, there is a fictional UEFA Champions League final between Real Madrid against Arsenal.

In the community

In 1985, Arsenal founded a community scheme, "Arsenal in the Community", which offered sporting, social inclusion, educational and charitable projects. The club support a number of charitable causes directly and in 1992 established The Arsenal Charitable Trust, which by 2006 had raised more than £2 million for local causes.[135] An ex-professional and celebrity football team associated with the club also raised money by playing charity matches.[136]

In the 2009–10 season Arsenal announced that they had raised a record breaking £818,897 for the Great Ormond Street Hospital Children's Charity. The original target was £500,000.[137]

Statistics and records

Arsenal's tally of 13 League Championships is the third highest in English football, after Manchester United (20) and Liverpool (18),[138] and they were the first club to reach a seventh and an eighth League Championship. As of May 2016, they are one of only six teams, the others being Manchester United, Blackburn Rovers, Chelsea, Manchester City and Leicester City, to have won the Premier League since its formation in 1992.[139]

They hold the highest number of FA Cup trophies, 12.[140] The club is one of only six clubs to have won the FA Cup twice in succession, in 2002 and 2003, and 2014 and 2015.[141] Arsenal have achieved three League and FA Cup "Doubles" (in 1971, 1998 and 2002), a feat only previously achieved by Manchester United (in 1994, 1996 and 1999).[56][142] They were the first side in English football to complete the FA Cup and League Cup double, in 1993.[143] Arsenal were also the first London club to reach the final of the UEFA Champions League, in 2006, losing the final 2–1 to Barcelona.[144]

Arsenal have one of the best top-flight records in history, having finished below fourteenth only seven times. The league wins and points they have accumulated are the second most in English top flight football.[3] They have been in the top flight for the most consecutive seasons (90 as of 2015–16).[4][145] Arsenal also have the highest average league finishing position for the 20th century, with an average league placement of 8.5.[5]

Arsenal hold the record for the longest run of unbeaten League matches (49 between May 2003 and October 2004).[55] This included all 38 matches of their title-winning 2003–04 season, when Arsenal became only the second club to finish a top-flight campaign unbeaten, after Preston North End (who played only 22 matches) in 1888–89.[54][146] They also hold the record for the longest top flight win streak.[147]

Arsenal set a Champions League record during the 2005–06 season by going ten matches without conceding a goal, beating the previous best of seven set by A.C. Milan. They went a record total stretch of 995 minutes without letting an opponent score; the streak ended in the final, when Samuel Eto'o scored a 76th-minute equaliser for Barcelona.[57]

David O'Leary holds the record for Arsenal appearances, having played 722 first-team matches between 1975 and 1993. Fellow centre half and former captain Tony Adams comes second, having played 669 times. The record for a goalkeeper is held by David Seaman, with 564 appearances.[148]

Thierry Henry is the club's top goalscorer with 228 goals in all competitions between 1999 and 2012,[149] having surpassed Ian Wright's total of 185 in October 2005.[150] Wright's record had stood since September 1997, when he overtook the longstanding total of 178 goals set by winger Cliff Bastin in 1939.[151] Henry also holds the club record for goals scored in the League, with 175,[149] a record that had been held by Bastin until February 2006.[152]

Arsenal's record home attendance is 73,707, for a UEFA Champions League match against RC Lens on 25 November 1998 at Wembley Stadium, where the club formerly played home European matches because of the limits on Highbury's capacity. The record attendance for an Arsenal match at Highbury is 73,295, for a 0–0 draw against Sunderland on 9 March 1935,[148] while that at Emirates Stadium is 60,161, for a 2–2 draw with Manchester United on 3 November 2007.[153]

Players

First-team squad

- As of 30 August 2016.[154]

Note: Flags indicate national team as defined under FIFA eligibility rules. Players may hold more than one non-FIFA nationality.

|

|

Out on loan

Note: Flags indicate national team as defined under FIFA eligibility rules. Players may hold more than one non-FIFA nationality.

|

|

UEFA Reserve squad

Note: Flags indicate national team as defined under FIFA eligibility rules. Players may hold more than one non-FIFA nationality.

|

|

Former players

Current technical staff

- As of August 2014.[162]

| Position | Name |

|---|---|

| Manager | |

| Assistant manager | |

| First-team coaches | |

| | |

| Goalkeeping coach | |

| Head of athletic performance enhancement | |

| Fitness coach | |

| Head physiotherapist | |

| Club doctor | |

| Kit manager | |

| Academy director | |

| Under-21s coaches | |

| | |

| Under-18s coach | |

| Under-16s coach | |

Managers

There have been eighteen permanent and five caretaker managers of Arsenal since the appointment of the club's first professional manager, Thomas Mitchell in 1897.[163] The club's longest-serving manager, in terms of both length of tenure and number of games overseen, is Arsène Wenger, who was appointed in 1996.[164][165] Wenger is also Arsenal's only manager from outside the United Kingdom.[165] Two Arsenal managers have died in the job – Herbert Chapman and Tom Whittaker.[166]

Honours

and FA Cups Timeline

As of June 2016.[167] Seasons in bold are Double-winning seasons, when the club won the league and FA Cup or a cup double of the FA Cup and League Cup. The 2003–04 season was the only 38-match league season unbeaten in English football history. A special gold version of the Premier League trophy was commissioned and presented to the club the following season.[168]

The Football League & Premier League

- First Division (until 1992) and Premier League

- Winners (13): 1930–31, 1932–33, 1933–34, 1934–35, 1937–38, 1947–48, 1952–53, 1970–71, 1988–89, 1990–91, 1997–98, 2001–02, 2003–04

- Winners (1): 1958–59

- Winners (1): 1988–89

The Football Association

- Winners (12): 1929–30, 1935–36, 1949–50, 1970–71, 1978–79, 1992–93, 1997–98, 2001–02, 2002–03, 2004–05, 2013–14, 2014–15 (shared record)

- FA Community Shield (FA Charity Shield before 2002)

- Winners (14): 1930, 1931, 1933, 1934, 1938, 1948, 1953, 1991 (shared), 1998, 1999, 2002, 2004, 2014, 2015

UEFA

- UEFA Cup Winners' Cup (European Cup Winners' Cup before 1994)

- Winners (1): 1993–94

- Winners (1): 1969–70

London Football Association

- Winners (1): 1890–91

- Winners (11): 1921–22, 1923–24, 1930–31, 1933–34, 1935–36, 1953–54, 1954–55, 1957–58, 1961–62, 1962–63, 1969–70 (record)

- Winners (1): 1889–90

Kent County Football Association

- Winners (1): 1889–90

Other

- ↑ Although not organised by The Football League, the Southern Professional Floodlit Cup was replaced by the Football League Cup in 1960. As the official precursor to the League Cup, it is included here under the Football League.

- ↑ Although not organised by UEFA, UEFA took over the Inter-Cities Fairs Cup in 1971 and reformed it into the UEFA Cup (now UEFA Europa League). As the official precursor to the UEFA Europa League, it is included here under UEFA.

Arsenal Ladies

Arsenal Ladies are the women's football club affiliated to Arsenal. Founded in 1987 by Vic Akers, they turned semi-professional in 2002 and are managed by Clare Wheatley. Akers now assumes the role of Honorary President of Arsenal Ladies.[174][175] Arsenal Ladies are the most successful team in English women's football. In the 2008–09 season, they won all three major English trophies – the FA Women's Premier League, FA Women's Cup and FA Women's Premier League Cup,[176] and, as of 2009, were the only English side to have won the UEFA Women's Cup, having done so in the 2006–07 season as part of a unique quadruple.[177] The men's and women's clubs are formally separate entities but have quite close ties; Arsenal Ladies are entitled to play once a season at the Emirates Stadium, though they usually play their home matches at Boreham Wood.[178] At present the ladies have won 42 trophies in their 28 year history.[179]

Footnotes

- ↑ Kelly, Andy (21 April 2013). "Arsenal's First Game – The Facts Finally Revealed « The History of Arsenal". www.blog.woolwicharsenal.co.uk. AISA Arsenal History Society. Archived from the original on 26 April 2013. Retrieved 7 June 2016.

- ↑ "The real capacity of Emirates Stadium". www.arsenal.com. The Arsenal Football Club plc. Retrieved 28 July 2016.

- 1 2 "English Premier League : Full All Time Table". statto.com. Retrieved 21 January 2016.

- 1 2 Ross, James; Heneghan, Michael; Orford, Stuart; Culliton, Eoin (23 June 2016). "English Clubs Divisional Movements 1888–2016". www.rsssf.com. Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation. Archived from the original on 5 August 2016. Retrieved 5 August 2016.

- 1 2 Hodgson, Guy (17 December 1999). "Football: How consistency and caution made Arsenal England's greatest". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 13 May 2016.

- ↑ "Herbert Chapman". National Football Museum. Retrieved 20 March 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 "Deloitte Football Money League" (PDF). Deloitte. Retrieved 21 January 2016.

- 1 2 "The Business Of Soccer". Forbes. Retrieved 12 May 2016.

- ↑ Woolwich and Plumstead were officially part of Kent until the creation of the County of London in 1889.

- For primary sources on the name, first meeting, and first match, see Kelly, Andy; Andrews, Mark (10 January 2014). "How Arsenal's name changed – Dial Square". The Arsenal History. Archived from the original on 4 August 2015. Retrieved 18 July 2016.

- Bernard Joy claims Danskin was captain at founding in Joy 2009, p. 2. Forward, Arsenal!

- Danskin was made official captain the next month, see Kelly, Andy; Andrews, Mark (13 January 2014). "How Arsenal's Name Changed – Royal Arsenal". The Arsenal History. Archived from the original on 1 May 2015. Retrieved 11 June 2016.

- ↑ Masters, Roy (1995). The Royal Arsenal, Woolwich. Britain in Old Photographs. Strood: Sutton Publishing. p. 91. ISBN 0-7509-0894-7.

- 1 2 Kelly, Andy; Andrews, Mark (13 January 2014). "How Arsenal's Name Changed – Royal Arsenal". The Arsenal History. Archived from the original on 1 May 2015. Retrieved 11 June 2016.

- ↑ Kelly, Andy (1 March 2012). "122 years ago today – Arsenal's first Silverware « The History of Arsenal". www.blog.woolwicharsenal.co.uk. Archived from the original on 29 March 2016. Retrieved 11 June 2016.

- ↑ Kelly, Andy (7 March 2012). "121 Years ago today – Royal Arsenal's last trophy « The History of Arsenal". www.blog.woolwicharsenal.co.uk. Archived from the original on 5 June 2016. Retrieved 11 June 2016.

- ↑ Kelly, Andy; Andrews, Mark (20 January 2014). "How Arsenal's Name Changed – Woolwich Arsenal". The Arsenal History. Archived from the original on 5 February 2016. Retrieved 11 June 2016.

- ↑ Attwood, Kelly & Andrews 2012, pp. 5–21. Woolwich Arsenal FC: 1893–1915 The club that changed football

- ↑ Davis, Sally (December 2007). "Woolwich Arsenal 1910 – the arrival of Hall and Norris". www.wrightanddavis.co.uk. Archived from the original on 10 April 2016. Retrieved 11 July 2016.

- ↑ Attwood, Kelly & Andrews 2012, p. 112-149. Woolwich Arsenal FC: 1893–1915 The club that changed football

- ↑ Kelly, Andy; Andrews, Mark (26 January 2014). "How Arsenal's Name Changed – The Arsenal". The Arsenal History. Archived from the original on 13 February 2014. Retrieved 11 June 2016.

- 1 2 Attwood, Kelly & Andrews 2012, pp. 43–64. Woolwich Arsenal FC: 1893–1915 The club that changed football

- ↑ It has been alleged that Arsenal's promotion, on historical grounds rather than merit, was thanks to underhand actions by Norris, who was chairman of the club at the time; see History of Arsenal F.C. (1886–1966) for more details. This speculation ranges from political machinations to outright bribery; no evidence of any wrongdoing has ever been found.

- A brief account is given in Soar & Tyler 2011, pp. 30–31. Arsenal 125 Years in the Making: The Official Illustrated History 1886–2011

- A more detailed account can be found in Spurling 2012, pp. 38–41. Rebels for the Cause: The Alternative History of Arsenal Football Club

- Various primary sources can be found in Kelly, Andy (19 January 2013). "Arsenal's Election To The First Division In 1919 « The History of Arsenal". Archived from the original on 21 July 2015.

- ↑ Kelly, Andy; Andrews, Mark (30 January 2014). "How Arsenal's Name Changed – Arsenal". The Arsenal History. Archived from the original on 6 August 2015. Retrieved 12 June 2016.

- ↑ Attwood, Kelly & Andrews 2012, p. 112. Woolwich Arsenal FC: 1893–1915 The club that changed football

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "A Conservation Plan for Highbury Stadium, London" (PDF). Islington Council. 14 February 2005. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 February 2012. Retrieved 4 February 2012.

- ↑ Page, Simon (18 Oct 2006). Herbert Chapman: The First Great Manager. Birmingham: Heroes Publishing. p. 139. ISBN 978-0-9543884-5-4.

- ↑ Barclay, Patrick (9 January 2014). "Arsenal: The Five-Year Plan". The Life and Times of Herbert Chapman: The Story of One of Football's Most Influential Figures. Orion. ISBN 978-0-297-86851-4.

- ↑ Whittaker & Peskett 1957. Tom Whittaker's Arsenal Story

- ↑ Buchan, Charles (1 April 2011) [First Published 1955]. Charles Buchan: A Lifetime in Football. Random House. pp. 95–97. ISBN 978-1-84596-927-1.

- ↑ Wilson, Jonathan (2013). Inverting the Pyramid: The History of Football Tactics (Fifth anniversary fully revised and updated edition. ed.). Orion Publishing Group, Limited. pp. 42–56. ISBN 978-1-4091-4586-8.

- ↑ Joy 2009, pp. 49,75. Forward, Arsenal!

- ↑ Kelly, Graham (2005). Terrace Heroes: The Life and Times of the 1930s Professional Footballer. Psychology Press. pp. 26, 81–83. ISBN 978-0-7146-5359-4.

- ↑ Brown, Tony (2007). Champions all! (PDF). Nottingham: SoccerData. pp. 6–7. ISBN 1-905891-02-4.

- ↑

- The new shirts are exhibited in Elkin & Shakeshaft 2014. The Arsenal Shirt: Iconic Match Worn Shirts from the History of the Gunners

- Newspaper accounts of the addition of white sleeves are provided by Andrews, Mark (7 June 2013). "Jumpers for Goalposts...No! Jumpers for Chapman's Iconic Kit Design". AISA Arsenal History Society. Archived from the original on 7 March 2016.

- The contemporary discussion around the first use of shirt numbers, and its initial trial by Chelsea F.C., is provided by Glackin, Neil (26 April 2014). "Numbered shirts and Chapman – re-writing the story once again". AISA Arsenal History Society. Archived from the original on 27 June 2014.

- ↑ Kelly, Andy (31 October 2015). "Arsenal underground station renamed earlier than believed". Archived from the original on 26 June 2016. Retrieved 26 June 2016.

- ↑ Bull, John (11 December 2015). "It's Arsenal Round Here: How Herbert Chapman Got His Station". Archived from the original on 23 February 2016. Retrieved 26 June 2016.

- ↑ Warrior, Yogi's (6 January 2013). "The Death Of Herbert Chapman Of Arsenal On This Day, 6th January 1934". Arsenal On This Day: A Prestigious History Of Football. Archived from the original on 1 July 2016. Retrieved 1 July 2016.

- ↑ Soar & Tyler 2011, p. 76. Arsenal 125 Years in the Making: The Official Illustrated History 1886–2011

- ↑ Rippon, Anton (21 October 2011). "Chapter Nine". Gas Masks for Goal Posts: Football in Britain During the Second World War. The History Press. ISBN 978-0-7524-7188-4.

- ↑ "Post-War Arsenal – Overview". Arsenal F.C. Retrieved 27 November 2009.

- ↑ Sowman & Wilson 2016. Arsenal: The Long Sleep 1953 – 1970: A view from the terrace

- ↑ Brown (2007). Champions all!. p. 7.

- ↑ Warrior, Yogi's (20 June 2012). "Bertie Mee Appointed Acting Manager Of Arsenaln This Day, 20th June 1966". Arsenal On This Day: A Prestigious History Of Football. Archived from the original on 7 July 2016. Retrieved 7 July 2016.

- 1 2 Ponting, Ivan (23 October 2001). "Bertie Mee". The Independent. Archived from the original on 6 March 2016. Retrieved 4 July 2016.

- ↑ Tossell, David; Wilson, Bob (13 Apr 2012). Seventy-One Guns: The Year of the First Arsenal Double. Random House. p. 105. ISBN 978-1-78057-473-8.

- ↑ Media Group, Arsenal (30 Jun 2008). "The Managers". www.arsenal.com. The Arsenal Football Club plc. Archived from the original on 5 April 2016. Retrieved 5 July 2016.

- ↑ Kelly, Andy (27 May 2015). "Arsenal's Complete FA Cup Final Record". The Arsenal History. Archived from the original on 18 April 2016. Retrieved 4 July 2016.

- ↑ A 2005 poll of English football fans rated the 1979 FA Cup Final the 15th greatest game of all time. Reference: Winter, Henry (19 April 2005). "Classic final? More like a classic five minutes". Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved 11 August 2008.

- ↑ Martin Keown was the 'fifth' member of the Back Four, but didn't play for the club between 1986 and 1993. Smyth, Rob (8 May 2009). "Football: Joy of Six: Rob Smyth picks the greatest defences". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 10 March 2016. Retrieved 7 July 2016.

- ↑ Clarke, Andy (26 March 2009). "Top Ten: Title Run-ins". Sky Sports. Retrieved 7 December 2009.

- ↑ Graham was banned for a year by the Football Association for his involvement in the scandal after he admitted he had received an "unsolicited gift" from Hauge.

- "Why the FA banned George Graham". The Independent. 10 November 1995. Archived from the original on 10 December 2011. Retrieved 15 July 2016.

- Bower, Tom (2003). Broken Dreams: Vanity, Greed and the Souring of British Football. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-7434-4033-2.

- ↑ Moore, Glenn (13 August 1996). "Rioch at odds with the system". The Independent. London. Retrieved 23 October 2009.

- ↑ Palmer, Myles (31 March 2011). The Professor: Arsène Wenger. Random House. pp. ix, 21, 90, 123, 148. ISBN 978-0-7535-4661-1.

- ↑

- For details, see Cross 2015. "Chapter 1: What's in a name?". Arsene Wenger: The Inside Story of Arsenal Under Wenger

- For more, see Ronay, Barney (5 August 2010). "Chapter 30 – The Enlightenment". The Manager: The absurd ascent of the most important man in football. Little, Brown Book Group. ISBN 978-0-7481-1770-3.

- For contemporary reaction, see "The menu for World Cup success". BBC. 23 May 1998. Retrieved 11 July 2016.

- For context of the broader use of science in English football, see Anthony, Strudwick (7 June 2016). "Part 1: Foundations of Soccer Science". Soccer Science. Human Kinetics. pp. 3–36. ISBN 978-1-4504-9679-7.

- ↑ The following analyses all indicate strong league performance across the Wenger period, given Arsenal's footballing outlays.

- For regression analysis on wage bills, see Kuper, Simon; Szymanski, Stefan (24 May 2012). "Chapter 6: Do managers matter? The cult of the white messiah". Soccernomics (Revised and Expanded ed.). HarperCollins Publishers. ISBN 978-0-00-746688-7.

- For regression on transfer spending, see Slaton, Zach (16 July 2012). "The 2011/12 Update to the All-Time Best Managers Versus the m£XIR Model | Pay As You Play". transferpriceindex.com. Archived from the original on 19 July 2012. Retrieved 11 July 2016.

- For regression on both, see Rodríguez, Plácido; Késenne, Stefan; García, Jaume (30 September 2013). "Chapter 3: Wages transfers and the variation of team performance in the English Premier League". The Econometrics of Sport. Edward Elgar Publishing. pp. 53–62. ISBN 978-1-78100-286-5.

- A bootstrapping approach for the period 2004–09 is applied in Bell, Adrian; Brooks, Chris; Markham, Tom (1 January 2013). "The performance of football club managers: skill or luck?". Economics & Finance Research. 1 (1): 19–30. doi:10.1080/21649480.2013.768829. ISSN 2164-9480.

- 1 2 Hughes, Ian (15 May 2004). "Arsenal the Invincibles". BBC Sport. Retrieved 11 August 2008.

- 1 2 Fraser, Andrew (25 October 2004). "Arsenal run ends at 49". BBC Sport. Retrieved 27 August 2008.

- 1 2 "Arsenal". Football Club History Database. Richard Rundle. Archived from the original on 6 November 2009. Retrieved 23 October 2009.

- 1 2 "2005/06: Ronaldinho delivers for Barça". UEFA. 17 May 2007. Archived from the original on 15 September 2008. Retrieved 11 August 2008.

- ↑ Aizlewood, John (23 July 2006). "Farewell Bergkamp, hello future". The Times. UK. Retrieved 23 October 2009.

- ↑ Hytner, David (18 May 2014). "Arséne Wenger savours FA Cup win over Hull as Arsenal end drought". The Guardian. UK. Retrieved 21 May 2014.

- ↑ Ronay, Barney (10 August 2014). "Arsenal cruise to Community Shield win over weakened Manchester City". The Guardian. UK. Retrieved 1 November 2014.

- ↑ Taylor, Daniel (30 May 2015). "Alexis Sánchez inspires Arsenal to win over Aston Villa". The Guardian. UK. Retrieved 30 May 2015.

- ↑ Cryer, Andy (2 August 2015). "Arsenal 1–0 Chelsea". BBC. UK. Retrieved 4 August 2015.

- 1 2 3 "The Crest". Arsenal F.C. Archived from the original on 12 August 2008. Retrieved 11 August 2008.

- ↑ "Arsenal v. Reed in the Court of Appeal". Swan Turton. 4 May 2003. Retrieved 7 July 2016.

- ↑ "Arsenal go for a makeover". BBC Sport. 1 February 2004. Retrieved 11 August 2008.

- ↑ "Crestfallen" (PDF). Arsenal Independent Supporters' Association. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 November 2006. Retrieved 11 August 2008.

- 1 2 "The Arsenal shirt badge". Arsenal F.C. Archived from the original on 30 October 2009. Retrieved 24 January 2010.

- ↑ "The Art Deco crest". Arsenal F.C. Archived from the original on 30 October 2009. Retrieved 24 January 2010.

- ↑ "125th anniversary crest". Arsenal F.C. Retrieved 1 May 2011.

- ↑ Soar & Tyler 2011, p. 20. Arsenal 125 Years in the Making: The Official Illustrated History 1886–2011

- ↑ "The Arsenal home kit". Retrieved 28 October 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 "Arsenal". Historical Football Kits. D & M Moor. Retrieved 8 December 2006.

- 1 2 3 4 "Arsenal Kit Design". Arsenal F.C. Archived from the original on 19 October 2008. Retrieved 8 November 2008.

- ↑ "Hibernian". Historical Football Kits. D & M Moor. Archived from the original on 21 August 2008. Retrieved 11 August 2008.

- ↑ Rui Matos Pereira (21 October 2005). "Secret of Braga's success". UEFA. Retrieved 23 January 2011.

- 1 2 "FA Cup Finals". Historical Football Kits. Retrieved 4 October 2013.

- ↑ "Arsenal Change Kits". Historical Football Kits. D & M Moor. Retrieved 27 November 2009.

- ↑ "Club Charter". Arsenal F.C. Retrieved 23 October 2009.

- ↑ Kent, David (8 May 2013). "Arsenal agree £30m-a-year deal with Puma in most lucrative kit contract in Britain". Daily Mail. London. Retrieved 9 September 2013.

- ↑ Inglis, Simon (1996) [1985]. Football Grounds of Britain (3rd ed.). London: CollinsWillow. pp. 16–17. ISBN 0-00-218426-5.

- ↑ "Suspension of the Plumstead Ground". The Times. 7 February 1895. p. 6.

- ↑ "Highbury". Arsenal F.C. Archived from the original on 11 January 2008.

- ↑ "Arsenal get Wembley go-ahead". BBC Sport. 24 July 1998. Retrieved 11 August 2008.

- ↑ Garner, Clare (18 August 1997). "Arsenal consider leaving hallowed marble halls". The Independent. London. Retrieved 23 October 2009.

- ↑ "Arsenal unveil new stadium plans". BBC Sport. 7 November 2000. Retrieved 11 August 2008.

- ↑ "Arsenal stadium delay". BBC Sport. 16 April 2003. Retrieved 11 August 2008.

- ↑ "Bergkamp given rousing farewell". BBC Sport. 22 July 2006. Retrieved 23 August 2007.

- ↑ "Arsenal name new ground". BBC Sport. 5 October 2004. Retrieved 11 August 2008.

- ↑ Dawes, Brian (2006). "The 'E' Word". Arsenal World. Footymad. Retrieved 11 August 2008.

- ↑ Riach, James (23 November 2012). "Arsenal's new Emirates sponsorship deal to fund transfers and salaries". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 17 December 2012.

- ↑ Emirates Stadium stands to be renamed Arsenal FC, 19 July 2010

- ↑ Taylor, David (21 October 1999). "Arsenal gets a complex". The Architects' Journal. Retrieved 20 January 2010.

- ↑ "The Training Centre". Arsenal F.C. Archived from the original on 12 August 2008. Retrieved 11 August 2008.

- ↑ "Youth sides to play at Meadow Park". 30 July 2013.

- ↑ Kempster, Tony. "Attendances 2007/08". Retrieved 11 August 2008.

- ↑ "All Time League Attendance Records". nufc.com. NUFC. 22 September 2015. Archived from the original on 6 April 2016. Retrieved 6 April 2016. Please note that some pre-war attendance figures used by this source were estimates and may not be entirely accurate.

- ↑ "German Bundesliga Stats: Team Attendance – 2010–11". ESPNsoccernet.

- ↑ "Camp Nou: Average attendance 79,390 | FCBarcelona.cat". Arxiu.fcbarcelona.cat. 17 May 2011. Retrieved 13 August 2012.

- ↑ "Barclays Premier League Stats: Team Attendance – 2010–11". ESPNsoccernet.

- ↑ "Spanish La Liga Stats: Team Attendance – 2010–11". ESPNsoccernet.

- ↑ "Fans Report 2006/2007" (Word document). Arsenal F.C. Archived from the original on 10 September 2008. Retrieved 7 September 2008.

- ↑ O’Connor, Ashling. "Liverpool lag in fight for global fan supremacy as TV row grows". thetimes.co.uk. The Times. Retrieved 22 March 2016.

- ↑ Coggin, Stewart. "The North London derby". Premier League. Archived from the original on 8 August 2008. Retrieved 7 September 2008.

- ↑ "The Classic: Arsenal-Manchester Utd". FIFA. 17 January 2007. Archived from the original on 24 August 2007. Retrieved 23 October 2009.

- ↑ "Club Rivalries Uncovered" (PDF). Football Fans Census. Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 September 2008. Retrieved 7 September 2008.

- ↑ "Football Rivalries Report 2008". The New Football Pools. Archived from the original on 5 March 2008. Retrieved 7 September 2008.

- 1 2 3 "The Arsenal Board". arsenal.com. Arsenal. Retrieved 28 March 2016.

- ↑ Scott, Matt & Allen, Katie (6 April 2007). "Takeover gains pace at Arsenal with 9.9% sale". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 11 August 2008.

- ↑ "Russian buys Dein's Arsenal stake". BBC News. 30 August 2007. Retrieved 11 August 2008.

- ↑ "Everton confirm sale of 49.9% of club to former Arsenal shareholder Farhad Moshiri". theguardian.co.uk. The Guardian. Retrieved 28 March 2016.

- ↑ "Kroenke increases stake in Arsenal Holdings". Arsenal F.C. 5 November 2009. Archived from the original on 8 November 2009. Retrieved 6 December 2009.

- ↑ "Kroenke nears Arsenal threshold". news.bbc.co.uk. BBC. Retrieved 28 March 2016.

- ↑ "US businessman Stan Kroenke agrees bid to buy Arsenal". news.bbc.co.uk. BBC. Retrieved 28 March 2016.

- ↑ "Stan Kroenke takes controlling stake in Arsenal with 62.89% of shares". theguardian.co.uk. The Guardian. Retrieved 28 March 2016.

- ↑ "Statement of Accounts and Annual Report 2006/2007 (p43)" (PDF). Arsenal Holdings plc. May 2007. Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 September 2008. Retrieved 11 August 2008.

- ↑ "Statement of Accounts and Annual Report 2009/2010 (p41)" (PDF). Arsenal Holdings plc. Sep 2010. Retrieved 12 January 2011.

- ↑ "Arsenal Holdings plc". isdx.xom. ISDX. Retrieved 28 March 2016.

- ↑ "Football 50 2015" (PDF). brandfinance.com. Brand Finance. Retrieved 22 March 2016.

- ↑ Markham, Dr Tom. "WHAT'S YOUR CLUB REALLY WORTH?". sportingintelligence.com. Sporting Intelligence. Retrieved 28 March 2016.

- ↑ Markham, Tom (2013). "What is the Optimal Method to Value a Football Club?". SSRN Electronic Journal. doi:10.2139/ssrn.2238265. Retrieved 28 March 2016.

- ↑ "Statement of Accounts and Annual Report 2014/15" (PDF). arsenal.com. Arsenal. Retrieved 28 March 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 Firsts, Lasts & Onlys: Football – Paul Donnelley (Hamlyn, 2010)

- ↑ "It Happened at Highbury: First live radio broadcast". Arsenal F.C. Retrieved 11 August 2008.

- ↑ "Happened on this day – 16 September". BBC Sport. 16 September 2002. Retrieved 11 August 2008.

- ↑ "History of Match of the Day". BBC Sport. 14 February 2003. Retrieved 11 August 2008.

- ↑ "Fans trial first live 3D sports event". Sydney Morning Herald. Associated Press. 1 February 2010. Retrieved 16 March 2010.

- ↑ "The Arsenal Stadium Mystery". IMDb. Retrieved 11 August 2008.

- 1 2 3 "Arsenal at the movies". Arseweb. Archived from the original on 26 July 2008. Retrieved 11 August 2008.

- ↑ "Nick Hornby". The Guardian. London. 22 July 2008. Retrieved 7 September 2008.

Critically acclaimed and commercial dynamite, Fever Pitch helped to make football trendy and explain its appeal to the soccerless

- ↑ "Fever Pitch (1997)". IMDb. Archived from the original on 15 October 2008. Retrieved 7 September 2008.

- ↑ "Fever Pitch (2005)". IMDb. Retrieved 7 September 2008.

- ↑ Noble, Kate (22 September 2002). "Boring, Boring Arsenal". Time. Retrieved 11 August 2008.

- ↑ May, John (19 May 2003). "No more boring, boring Arsenal". BBC Sport. Retrieved 7 September 2008.

- ↑ Association Football – Harry Enfield – Mr Cholmondley-Warner YouTube

- ↑ "Arsenal Charity Ball raises over £60,000". Arsenal F.C. 11 May 2006. Retrieved 11 August 2008.

- ↑ "Ex-Pro and Celebrity XI". Arsenal F.C. Archived from the original on 22 August 2008. Retrieved 11 August 2008.

- ↑ Arsenal smash fundraising target for GOSH Arsenal FC, 2 August 2010

- ↑ Ross, James M (28 August 2009). "England – List of Champions". RSSSF. Retrieved 23 October 2009.

- ↑ Ross, James M. (6 May 2016). "FA Premier League Champions 1993–2016". Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation. Archived from the original on 18 June 2016. Retrieved 15 July 2016.

- ↑ Ross, James M (12 June 2009). "England FA Challenge Cup Finals". RSSSF. Retrieved 23 October 2009.

- ↑ Ross, James M (12 June 2009). "England FA Challenge Cup Finals". RSSSF. Archived from the original on 24 October 2008. Retrieved 23 October 2009.

- ↑ Stokkermans, Karel (24 September 2009). "Doing the Double: Countrywise Records". RSSSF. Retrieved 23 October 2009.

- ↑ Collins, Roy (20 May 2007). "Mourinho collects his consolation prize". The Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved 6 December 2009.

Chelsea's Cup came wrapped in an extra ribbon, only the second team after Arsenal in 1993 to win both domestic cups.

- ↑ "Arsenal Football Club". Premier League. Archived from the original on 13 September 2008. Retrieved 11 August 2008.

- ↑ James, Josh. "All-time Arsenal". arsenal.com. Arsenal. Retrieved 20 March 2016.

- ↑ "The Unbeaten Record". Arsenal Broadband. Retrieved 10 December 2011.

- ↑ "Records". statto.com. Retrieved 22 March 2016.

- 1 2 "Club Records". Arsenal F.C. Retrieved 23 October 2009.

- 1 2 "Goalscoring Records". Arsenal.com. Retrieved 13 September 2013.

- ↑ "Wright salutes Henry's goal feat". BBC Sport. 19 October 2005. Retrieved 11 August 2008.

- ↑ Ward, Rupert. "Arsenal vs Bolton. 13/09/97". Arseweb. Retrieved 11 August 2008.

- ↑ "Arsenal 2–3 West Ham". BBC Sport. 1 February 2006. Retrieved 23 October 2009.

- ↑ "Man Utd game attracts record attendance". Arsenal F.C. 5 November 2007. Retrieved 11 August 2008.

- ↑ "Players". Arsenal F.C. Retrieved 11 July 2016.

- ↑ http://www.arsenal.com/news/news-archive/20160804/szczesny-returns-to-roma-on-loan

- ↑ "Breaking: AFC Bournemouth complete loan signing of Jack Wilshere from Arsenal". AFC Bournemouth Official Site. 31 August 2016. Retrieved 31 August 2016.

- ↑ http://www.arsenal.com/news/news-archive/20160830/calum-chambers-loaned-to-middlesbrough

- ↑ http://www.arsenal.com/news/news-archive/20160821/campbell-joins-sporting-clube-on-loan

- ↑ http://www.vfb.de/de/aktuell/meldungen/news/2016/news-transfer-1617/page/11951-1-3-.html?f3

- ↑ "Reserve Players". Arsenal F.C. Retrieved 13 August 2009.

- ↑ "Arsenal FC". UEFA. Retrieved 13 September 2016.

- ↑ "Staff". Arsenal F.C. Retrieved 11 October 2014.

- ↑ Soar & Tyler (2005). The Official Illustrated History of Arsenal. p. 30.

- ↑ "Wenger hungry for further success". BBC Sport. 2 October 2009. Retrieved 6 December 2009.

- 1 2 Davies, Christopher (8 December 2008). "700 and not out: Arsenal boss Wenger looking to celebrate memorable day at Porto". Daily Mail. UK. Retrieved 6 December 2009.

- ↑ "The Managers". Arsenal F.C. Archived from the original on 7 September 2008. Retrieved 7 September 2008.

- ↑ For a record of all matches participated in by Arsenal, see the AISA Arsenal History Society's line-ups database, listed first. See subsequent sources for corroboration.

- Kelly, Andy. "Arsenal first team line ups". The Arsenal History. Archived from the original on 15 June 2016. Retrieved 15 June 2016.

- "Honours". Arsenal F.C. Retrieved 18 September 2015.

- James, Josh. "Cups of plenty". www.arsenal.com. Arsenal. Retrieved 11 April 2016.

- "Complete cup finals". Statto Organisation. Retrieved 24 September 2015.

- "Arsenal". Football Club History Database. Richard Rundle. Archived from the original on 6 November 2009. Retrieved 23 October 2009.

- Ross, James M. (29 October 2015). "England – List of FA Charity/Community Shield Matches". Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation (RSSSF). Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 9 April 2016.

- Michael J Slade (2013). The History of the English Football League: Part One—1888–1930. Strategic Book Publishing. ISBN 1-62516-183-2.

- Joy 2009. Forward, Arsenal!

- "AISA Arsenal History Society". Retrieved 11 April 2016.

- ↑ "Special trophy for Gunners". BBC Sport. 18 May 2004. Retrieved 5 June 2016.

- 1 2 3 "125 years of Arsenal history – 1886–1891". Arsenal F.C. 5 December 2011. Retrieved 3 September 2015.

- ↑ "Royal Arsenal in the London Senior Cup; retiring as cup winners". The History of Arsenal (AISA Arsenal History Society). 22 November 2013. Retrieved 2 September 2015.

- ↑ Haynes, Graham (1998). A-Z Of Bees: Brentford Encyclopaedia. Yore Publications. p. 82. ISBN 1-874427-57-7.

- ↑ "List of winners of discontinued County Cups". London FA. Archived from the original on 13 March 2007. Retrieved 6 June 2016.

- ↑ Attwood, Tony (16 November 2013). "Arsenal in the London Challenge Cup". The History of Arsenal (AISA Arsenal History Society). Retrieved 31 March 2016.

- ↑ Football Club, Arsenal. "Arsenal Ladies". Ladies History.

- ↑ "Clare Wheatley". Arsenal FC. Retrieved 16 March 2015.

- ↑ "Arsenal Ladies Honours". Arsenal F.C. Retrieved 21 May 2007.

- ↑ Mawhinney, Stuart (7 May 2007). "Arsenal clinch quadruple". The Football Association. Retrieved 23 October 2009.

- ↑ "Get to Boreham Wood". Arsenal F.C. Archived from the original on 6 September 2008. Retrieved 7 September 2008.

- ↑ Football Club, Arsenal. "Arsenal Ladies". Ladies History. Retrieved 3 December 2016.

Further reading

- Attwood, Tony; Kelly, Andy; Andrews, Mark (1 August 2012). Woolwich Arsenal FC: 1893–1915 The club that changed football (First ed.). First and Best in Education. ISBN 978-1-86083-787-6.

- Callow, Nick (11 April 2013). The Official Little Book of Arsenal. Carlton Books Ltd. ISBN 978-1-84732-680-5.

- Castle, Ian (30 August 2012). Arsenal. FeedaRead.com. ISBN 978-1-78176-752-8.

- Cross, John (17 September 2015). Arsene Wenger: The Inside Story of Arsenal Under Wenger. Simon & Schuster UK. ISBN 978-1-4711-3793-8.

- Elkin, James; Shakeshaft, Simon (1 November 2014). The Arsenal Shirt: Iconic Match Worn Shirts from the History of the Gunners. Vision Sports Publishing. ISBN 978-1-909534-26-1.

- Fynn, Alex; Whitcher, Kevin (18 August 2011). Arsènal: The Making of a Modern Superclub (3rd ed.). Vision Sports Publishing. ISBN 978-1-907637-31-5.

- Glanville, Brian (2011). Arsenal Football Club: From Woolwich to Whittaker. GCR Books. ISBN 978-0-9559211-7-9.

- Hayes, Dean (2007). Arsenal: The Football Facts. John Blake. ISBN 978-1-84454-433-2.

- Hornby, Nick (1992). Fever Pitch. Indigo. ISBN 978-0-575-40015-3.

- Joy, Bernard (2009) [First Published 1952]. Forward, Arsenal! (Republished ed.). GCR Books Limited. ISBN 978-0-9559211-1-7.

- Lane, David (28 August 2014). Arsenal 'Til I Die: The Voices of Arsenal FC Supporters. Meyer & Meyer Sport. ISBN 978-1-78255-038-9.

- Maidment, Jem (2008). The Official Arsenal Encyclopedia: A Comprehensive A-Z of London's Most Successful Club (revised ed.). Hamlyn. ISBN 978-0-600-61888-1.

- Mangan, Andrew; Lawrence, Amy; Auclair, Philippe; Allen, Andrew (7 December 2011). So Paddy Got Up: An Arsenal anthology. Portnoy Publishing. ISBN 978-0-9569813-7-0.

- Roper, Alan (1 November 2003). Real Arsenal Story: In the Days of Gog. Wherry Publishing. ISBN 978-0-9546259-0-0.

- Soar, Phil; Tyler, Martin (3 October 2011). Arsenal 125 Years in the Making: The Official Illustrated History 1886–2011. Hamlyn. ISBN 978-0-600-62353-3.

- Sowman, John; Wilson, Bob (18 January 2016). Arsenal: The Long Sleep 1953 – 1970: A view from the terrace. Hamilton House. ISBN 978-1-86083-837-8.

- Spragg, Iain; Clarke, Adrian (8 October 2015). The Official Arsenal FC Book of Records (2 ed.). Carlton Books Ltd. ISBN 978-1-78097-668-6.

- Spurling, Jon (2 November 2012). Rebels for the Cause: The Alternative History of Arsenal Football Club (New ed.). Random House. ISBN 978-1-78057-486-8.

- Spurling, Jon (21 August 2014). Highbury: The Story of Arsenal In N.5. Orion. ISBN 978-1-4091-5306-1.

- Stammers, Steve (7 November 2008). Arsenal: The Official Biography: The Compelling Story of an Amazing Club (First ed.). Hamlyn. ISBN 978-0-600-61892-8.

- Wall, Bob (1969). Arsenal from the Heart. Souvenir Press Limited. ISBN 978-0-285-50261-1.

- Watt, Tom (13 October 1995). The End: 80 Years of Life on the Terraces. Mainstream Publishing Company, Limited. ISBN 978-1-85158-793-3.

- Whittaker, Tom; Peskett, Roy (1957). Tom Whittaker's Arsenal Story (First ed.). Sporting Handbooks.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Arsenal F.C.. |

| Wikinews has news related to: |

Official websites

- Official website

- Arsenal at the Premier League official website

- Arsenal at the UEFA official website

News sites

- Arsenal on BBC Sport: Club news – Recent results – Upcoming fixtures

- Arsenal news from Sky Sports

Other

- Arsenal F.C. companies grouped at OpenCorporates