Arghun

| Arghun | |

|---|---|

| Khan | |

| |

| Reign | 1284– 7 March 1291 |

| Predecessor | Tekuder |

| Successor | Gaykhatu |

| Dynasty | Ilkhanate |

| Father | Abaqa |

| Religion | Buddhism; baptized at birth as Christian |

Arghun Khan aka Argon (Mongolian Cyrillic: Аргун хан; c. 1258 – 7 March 1291[1]) was the fourth ruler of the Mongol empire's Ilkhanate, from 1284 to 1291. He was the son of Abaqa Khan, and like his father, was a devout Buddhist (although pro-Christian). He was known for sending several embassies to Europe in an unsuccessful attempt to form a Franco-Mongol alliance against the Muslims in the Holy Land. It was also Arghun who requested a new bride from his great-uncle Kublai Khan. The mission to escort the young Kökötchin across Asia to Arghun was reportedly taken by Marco Polo. Arghun died before Kökötchin arrived, so she instead married Arghun's son, Ghazan.

Biography

Arghun was born to Abaqa Khan and his Christian princess wife, Haimash Khatun. Arghun himself had multiple wives, and his mother-in-law Bulughan Khatun raised Arghun's two sons Ghazan (whose birth mother was Qutlugh) and Öljeitü (whose birth mother was Uruk Khatun[2]), both of whom later succeeded him and eventually converted to Islam. Arghun had Öljeitü baptized as a Christian at birth, and gave him the name Nikolya "Nicholas" after Pope Nicholas IV.[3] According to the Dominican missionary Ricoldo of Montecroce, he was "a man given to the worst of villainy, but for all that a friend of the Christians".[4]

One of the sisters of Arghun, Oljath, was married to the Georgian King Vakhtang II.[5]

Arghun was a Buddhist, but as did most Turco-Mongols, he showed great tolerance for all faiths, even allowing Muslims to be judged under Islamic Law. His grand vizier and minister of finance, Sa'ad al-Dawla, was a Jew. Sa'ad was effective in restoring order to the Ilkhanate's government, in part by aggressively denouncing the abuses of the Mongol military leaders.[6]

Conflicts

Arghun's reign was relatively peaceful, and there were few conflicts with his fellow Mongols. He did fight a brief campaign against the Chagatai Khanate in Khorasan. In 1289-1290, he had to deal with an upheaval of the Oirat emir Nauruz, who had to flee to Transoxonia.

In 1288 and 1290, he had repelled two separate invasion forces from the Golden Horde under Tulabuga in the area of the Caucasus.

During Arghun's reign, the Egyptian Mamluks were continuously reinforcing their power in Syria. The Mamluk Sultan Qalawun recaptured Crusader territories, some of which, such as Tripoli, had been vassal states of the Il Khans. The Mamluks had captured the northern fortress of Margat in 1285, Lattakia in 1287, and completed the Fall of Tripoli in 1289.[7]

Relations with Christian powers

Arghun was one of a long line of Genghis-Khanite rulers who had endeavored to establish a Franco-Mongol alliance with the Europeans, against their common foes the Mamluks of Egypt. Arghun had promised his potential allies that if Jerusalem were to be conquered, he would have himself baptized. Yet by the late 13th century, Western Europe was no longer as interested in the crusading effort, and Arghun's missions were ultimately fruitless.[8]

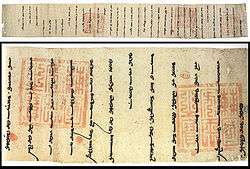

First mission to the Pope

In 1285, Arghun sent an embassy and a letter to Pope Honorius IV, a Latin translation of which is preserved in the Vatican.[9][10] Arghun's letter mentioned the links that Arghun's family had to Christianity, and proposed a combined military conquest of Muslim lands:[11]

"As the land of the Muslims, that is, Syria and Egypt, is placed between us and you, we will encircle and strangle ("estrengebimus") it. We will send our messengers to ask you to send an army to Egypt, so that us on one side, and you on the other, we can, with good warriors, take it over. Let us know through secure messengers when you would like this to happen. We will chase the Saracens, with the help of the Lord, the Pope, and the Great Khan."— Extract from the 1285 letter from Arghun to Honorius IV, Vatican[12]

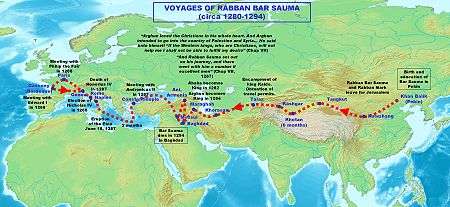

Second mission, to Kings Philip and Edward

Apparently left without an answer, Arghun sent another embassy to European rulers in 1287, headed by the Ongut Turk Nestorian monk from China Rabban Bar Sauma,[13] with the objective of contracting a military alliance to fight the Muslims in the Middle East, and take the city of Jerusalem.[9][14] The responses were positive but vague. Sauma returned in 1288 with positive letters from Pope Nicholas IV, Edward I of England, and Philip IV the Fair of France.[15]

Third mission

In 1289, Arghun sent a third mission to Europe, in the person of Buscarel of Gisolfe, a Genoese who had settled in Persia. The objective of the mission was to determine at what date concerted Christian and Mongol efforts could start. Arghun committed to march his troops as soon as the Crusaders had disembarked at Saint-Jean-d'Acre. Buscarel was in Rome between July 15 and September 30, 1289, and in Paris in November–December 1289. He remitted a letter from Arghun to Philippe le Bel, answering to Philippe's own letter and promises, offering the city of Jerusalem as a potential prize, and attempting to fix the date of the offensive from the winter of 1290 to spring of 1291:[17]

"Under the power of the eternal sky, the message of the great king, Arghun, to the king of France..., said: I have accepted the word that you forwarded by the messengers under Saymer Sagura (Bar Sauma), saying that if the warriors of Il Khaan invade Egypt you would support them. We would also lend our support by going there at the end of the Tiger year’s winter [1290], worshiping the sky, and settle in Damascus in the early spring [1291].If you send your warriors as promised and conquer Egypt, worshiping the sky, then I shall give you Jerusalem. If any of our warriors arrive later than arranged, all will be futile and no one will benefit. If you care to please give me your impressions, and I would also be very willing to accept any samples of French opulence that you care to burden your messengers with.

I send this to you by Myckeril and say: All will be known by the power of the sky and the greatness of kings. This letter was scribed on the sixth of the early summer in the year of the Ox at Ho’ndlon."

Buscarello was also bearing a memorandum explaining that the Mongol ruler would prepare all necessary supplies for the Crusaders, as well as 30,000 horses.[20] Buscarel then went to England to bring Arghun's message to King Edward I. He arrived in London January 5, 1290. Edward, whose answer has been preserved, answered enthusiastically to the project but remained evasive about its actual implementation, for which he deferred to the Pope.[21]

Assembly of a raiding naval force

In 1290, Arghun launched a shipbuilding program in Baghdad, with the intent of having war galleys which would harass the Mamluk commerce in the Red Sea. The Genoese sent a contingent of 800 carpenters and sailors, to help with the shipbuilding. A force of arbaletiers was also sent, but the enterprise apparently foundered when the Genoese government ultimately disowned the project, and an internal fight erupted at the Persian Gulf port of Basra among the Genoese (between the Guelph and Ghibelline factions).[20][22]

Fourth mission

Arghun sent a fourth mission to European courts in 1290, led by Andrew Zagan (or Chagan), who was accompanied by Buscarel of Gisolfe and a Christian named Sahadin.[23]

In 1291, Pope Nicholas IV proclaimed a new Crusade and negotiated agreements with Arghun, Hetoum II of Armenia, the Jacobites, the Ethiopians and the Georgians. On January 5, 1291, Nicholas addressed a vibrant prayer to all the Christians to save the Holy Land, and predicators started to rally Christians to follow Edward I in a Crusade.[24]

However, the efforts were too little and too late. On May 18, 1291, Saint-Jean-d'Acre was conquered by the Mamluks in the Siege of Acre.

In August 1291, Pope Nicholas wrote a letter to Arghun informing him of the plans of Edward I to go on a Crusade to recapture the Holy Land, stating that the Crusade could only be successful with the help of the "powerful arm" of the Mongols.[25] Nicolas repeated an oft-told theme of the Crusader communications to the Mongols, asking Arghun to receive baptism and to march against the Mamluks.[26] However Arghun himself had died on March 10, 1291, and Pope Nicholas IV would die in March 1292, putting an end to their attempts at combined action.[27]

Edward I sent an ambassador to Arghun's successor Gaikhatu in 1292 in the person of Geoffrey de Langley, but extensive contacts would only resume under Arghun's son Ghazan.

According to the 20th-century historian Runciman, "Had the Mongol alliance been achieved and honestly implemented by the West, the existence of Outremer would almost certainly have been prolonged. The Mamluks would have been crippled if not destroyed; and the Ilkhanate of Persia would have survived as a power friendly to the Christians and the West"[23]

Death

Arghun died on March 7, 1291,[28] and was succeeded by his brother Gaykhatu.

The 13th century saw such a vogue of Mongol things in the West that many new-born children in Italy were named after Genghis-Khanite rulers, including Arghun: names such as Can Grande ("Great Khan"), Alaone (Hulagu), Argone (Arghun) or Cassano (Ghazan) are recorded with a high frequency.[29]

Marco Polo

Arghun was the stated reason why Marco Polo was able to return to Venice after 23 years of absence. Arghun, having lost his favorite wife Bolgana, asked his grand uncle and ally Kublai Khan to send him one of Bolgana's relatives as a new bride. The choice fell to the 17-year-old Kökötchin ("Blue, or Celestial, Dame"). Marco Polo was given the task of accompanying the princess through land and sea routes, navigating on a Mongolian ship through the Indian Ocean to Persia. The journey took two years and Arghun died in the meantime, so Kökötchin instead married Arghun's son Ghazan.

See also

- Timeline of Buddhism (see 1285 CE)

Notes

- ↑ Grousset, René (1970). The Empire of the Steppes: A History of Central Asia. Rutgers University Press. p. 376. ISBN 9780813513041.

- ↑ Ryan, James D. (November 1998). "Christian wives of Mongol khans: Tartar queens and missionary expectations in Asia". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society. 8 (9): 411–421. doi:10.1017/s1356186300010506.

- ↑ "Arghun had one of his sons baptized, Khordabandah, the future Oljaitu, and in the Pope's honor, went as far as giving him the name Nicholas", Histoire de l'Empire Mongol, Jean-Paul Roux, p.408

- ↑ Jackson, p.176

- ↑ Grousset, p.846

- ↑ Mantran, Robert (Fossier, Robert, ed.) "A Turkish or Mongolian Islam" in The Cambridge Illustrated History of the Middle Ages: 1250-1520, p. 298

- ↑ Tyerman, p.817

- ↑ Prawdin, p. 372. "Argun revived the idea of an alliance with the West, and envoys from the Ilkhans once more visited European courts. He promised the Christians the Holy Land, and declared that as soon as they had conquered Jerusalem he would have himself baptised there. The Pope sent the envoys on to Philip the Fair of France and to Edward I of England. But the mission was fruitless. Western Europe was no longer interested in crusading adventures.

- 1 2 Runciman, p.398

- ↑ "This Arghon loved the Christians very much, and several times asked to the Pope and the king of France how they could together destroy all the Sarazins" - Le Templier de Tyr - French original:"Cestu Argon ama mout les crestiens et plusors fois manda au pape et au roy de France trayter coment yaus et luy puissent de tout les Sarazins destruire" Guillame de Tyr (William of Tyre) "Historia rerum in partibus transmarinis gestarum" #591

- ↑ The Crusades Through Arab Eyes p. 254: Arghun, grandon of Hulagu, "had resurrected the most cherished dream of his predecessors: to form an alliance with the Occidentals and thus to trap the Mamluk sultanate in a pincer movement. Regular contacts were established between Tabriz and Rome with a view to organizing a joint expedition, or at least a concerted one."

- ↑ Quote in "Histoires des Croisades III", Rene Grousset, p700

- ↑ Morris Rossabi (28 November 2014). From Yuan to Modern China and Mongolia: The Writings of Morris Rossabi. BRILL. pp. 385–386. ISBN 978-90-04-28529-3.

- ↑ Rossabi, p. 99

- ↑ Boyle, in Camb. Hist. Iran V, pp. 370-71; Budge, pp. 165-97. Source

- ↑ Grands Documents de l'Histoire de France, Archives Nationales de France, p.38, 2007.

- ↑ Runciman, p.401

- ↑ Alternative translation of Arghun's letter

- ↑ For another translation here

- 1 2 Jean Richard, p.468

- ↑ "Histoire des Croisades III", p.713, Rene Grousset.

- ↑ "Only a contingent of 800 Genoese arrived, whom he (Arghun) employed in 1290 in building shipd at Baghdad, with a view to harassing Egyptian commerce at the southern approaches to the Red Sea", p.169, Peter Jackson, The Mongols and the West

- 1 2 Runciman, p.402

- ↑ Dailliez, p.324-325

- ↑ Schein, p.809

- ↑ Jackson, p.169

- ↑ Runciman, p.412

- ↑ "He died on March 7, 1291." Steppes, p. 376

- ↑ Peter Jackson, The Mongols and the West, p.315

References

- Le Templier de Tyr (c. 1300), Online (Original French).

- "The Monks of Kublai Khan Emperor of China", Sir E. A. Wallis Budge. Online

- Dailliez, Laurent (1972). Les Templiers (in French). Editions Perrin. ISBN 2-262-02006-X.

- Foltz, Richard, Religions of the Silk Road, New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010, ISBN 978-0-230-62125-1

- Grousset, René (1935). Histoire des Croisades III, 1188-1291 (in French). Editions Perrin. ISBN 2-262-02569-X.

- Grousset, Rene, The Empire of the Steppes: a History of Central Asia, Naomi Walford, (tr.), New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1970.

- Jackson, Peter (2005). The Mongols and the West: 1221-1410. Longman. ISBN 978-0-582-36896-5.

- Lebédel, Claude (2006). Les Croisades, origines et conséquences (in French). Editions Ouest-France. ISBN 2-7373-4136-1.

- Maalouf, Amin (1984). The Crusades Through Arab Eyes. New York: Schocken Books. ISBN 0-8052-0898-4.

- Prawdin, Michael (1961) [1940]. Mongol Empire. Collier-Macmillan Canada. ISBN 1-4128-0519-8.

- Richard, Jean (1996). Histoire des Croisades. Fayard. ISBN 2-213-59787-1.

- Rossabi, Morris (1992). Voyager from Xanadu: Rabban Sauma and the first journey from China to the West. Kodansha International Ltd. ISBN 4-7700-1650-6.

- Runciman, Steven (1987 (first published in 1952-1954)). A history of the Crusades 3. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-013705-7. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - Schein, Sylvia (October 1979). "Gesta Dei per Mongolos 1300. The Genesis of a Non-Event". The English Historical Review. 94 (373): 805–819. doi:10.1093/ehr/XCIV.CCCLXXIII.805. JSTOR 565554.

- Tyerman, Christopher (2006). God's War: A New History of the Crusades. Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-02387-0.

External links

| Regnal titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Tekuder |

Ilkhanid Dynasty 1284– 7 March 1291 |

Succeeded by Gaykhatu |