Semitic languages

| Semitic | |

|---|---|

| Syro-Arabian | |

| Geographic distribution: |

Western Asia, North Africa, Northeast Africa, Malta |

| Linguistic classification: |

|

| Proto-language: | Proto-Semitic |

| Subdivisions: |

|

| ISO 639-2 / 5: | sem |

| Glottolog: | semi1276[1] |

|

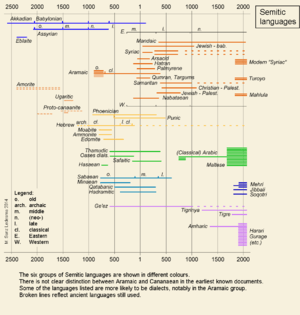

Chronology mapping of Semitic languages | |

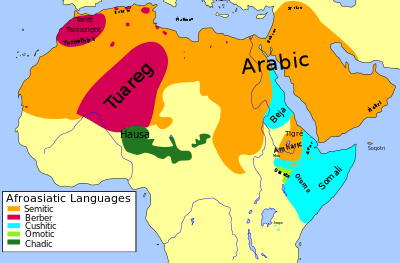

The Semitic languages are a branch of the Afroasiatic language family originating in the Middle East. Semitic languages are spoken by more than 330 million people across much of Western Asia, Anatolia, North Africa and the Horn of Africa, as well as in often large expatriate communities in North America and Europe, with smaller communities in South America, Australasia, the Caucasus and Central Asia. The terminology was first used in the 1780s by members of the Göttingen School of History,[2] who derived the name from Shem, one of the three sons of Noah in the Book of Genesis.

The most widely spoken Semitic languages today are (numbers given are for native speakers only) Arabic (300 million),[3] Amharic (22 million),[4] Tigrinya (7 million),[5] Hebrew (unknown; 5 million native and non-native L1 speakers),[6] Aramaic (575,000 to 1 million fluent speakers)[7][8][9] and Maltese (520,000 speakers).[10]

Semitic languages occur in written form from a very early historical date, with East Semitic Akkadian and Eblaite texts (written in a script adapted from Sumerian cuneiform) appearing from the 29th century BCE and the 25th century BCE in Mesopotamia and the northern Levant respectively. However, most scripts used to write Semitic languages are abjads – a type of alphabetic script that omits some or all of the vowels, which is feasible for these languages because the consonants in the Semitic languages are the primary carriers of meaning.

Among them are the Ugaritic, Phoenician, Aramaic, Hebrew, Syriac, Arabic, and South Arabian alphabets. The Ge'ez script, used for writing the Semitic languages of Ethiopia and Eritrea, is technically an abugida – a modified abjad in which vowels are notated using diacritic marks added to the consonants at all times, in contrast with other Semitic languages which indicate diacritics based on need or for introductory purposes. Maltese is the only Semitic language written in the Latin script and the only Semitic language to be an official language of the European Union.

The Semitic languages are notable for their nonconcatenative morphology. That is, word roots are not themselves syllables or words, but instead are isolated sets of consonants (usually three, making a so-called triliteral root). Words are composed out of roots not so much by adding prefixes or suffixes, but rather by filling in the vowels between the root consonants (although prefixes and suffixes are often added as well). For example, in Arabic, the root meaning "write" has the form k-t-b. From this root, words are formed by filling in the vowels and sometimes adding additional consonants, e.g. كتاب kitāb "book", كتب kutub "books", كاتب kātib "writer", كتّاب kuttāb "writers", كتب kataba "he wrote", يكتب yaktubu "he writes", etc.

Name and identification

The similarity of the Hebrew, Arabic and Aramaic languages was accepted by Jewish and Islamic scholars since medieval times. The languages were familiar to Western European scholars due to historical contact with neighbouring Islamic countries and through Biblical studies, and a comparative analysis of Hebrew, Arabic, and Aramaic was published in Latin in 1538 by Guillaume Postel.[11] Almost two centuries later, Hiob Ludolf described the similarities between these three languages and the Ethiopian Semitic languages.[11] However, neither scholar named this grouping as "Semitic".[11]

The term was created by members of the Göttingen School of History, and specifically by August Ludwig von Schlözer[12] (1781)[13] and Johann Gottfried Eichhorn[14] (1787)[15] first coined the name "Semitic" in the late 18th century to designate the languages closely related to Arabic, Aramaic, and Hebrew.[12] The choice of name was derived from Shem, one of the three sons of Noah in the genealogical accounts of the biblical Book of Genesis,[12] or more precisely from the Koine Greek rendering of the name, Σήμ (Sēm). Eichhorn is credited with popularising the term,[16] particularly via a 1795 article "Semitische Sprachen" (Semitic languages) in which he justified the terminology against criticism that Hebrew and Canaanite were the same language despite Canaan being "Hamitic" in the Table of Nations:[17][16]

In the Mosaic Table of Nations, those names which are listed as Semites are purely names of tribes who speak the so-called Oriental languages and live in Southwest Asia. As far as we can trace the history of these very languages back in time, they have always been written with syllabograms or with alphabetic script (never with hieroglyphs or pictograms); and the legends about the invention of the syllabograms and alphabetic script go back to the Semites. In contrast, all Hamitic peoples originally used hieroglyphs, until they here and there, either through contact with the Semites, or through their settlement among them, became familiar with their syllabograms or alphabetic script, and partly adopted them. Viewed from this aspect too, with respect to the alphabet used, the name "Semitic languages" is completely appropriate.

Previously these languages had been commonly known as the "Oriental languages" in European literature.[12][14] In the 19th century, "Semitic" became the conventional name; however, an alternative name, "Syro-Arabian languages", was later introduced by James Cowles Prichard and used by some writers.[14]

History

Ancient Semitic-speaking peoples

There are several locations proposed as possible sites for prehistoric origins of Semitic-speaking peoples: Mesopotamia, The Levant, Mediterranean, the Arabian Peninsula, and North Africa.[18]

Common Era (AD)

Syriac, a fifth century BCE Assyrian[19] Mesopotamian descendant of Aramaic used in northeastern Syria and Mesopotamia,[20] rose to importance as a literary language of early Christianity in the third to fifth centuries and continued into the early Islamic era.

With the advent of the early Muslim conquests of the seventh and eighth centuries, the hitherto largely uninfluential Arabic language slowly but surely replaced many of the indigenous Semitic languages and cultures of the Near East. Both the Near East and North Africa saw an influx of Muslim Arabs from the Arabian Peninsula, followed later by non-Semitic Muslim Iranian and Turkic peoples. The previously dominant Aramaic dialects gradually began to be sidelined, however descendant dialects of Aramaic (including Assyrian Neo-Aramaic, Chaldean Neo-Aramaic, Turoyo and Mandaic) survive to this day among the Assyrians and Mandaeans of northern Iraq, northwestern Iran, northeastern Syria and southeastern Turkey. The Arabs spread their Central Semitic language to North Africa where it gradually replaced Coptic and many Berber languages (although Berber is still largely extant), and for a time to the Iberian Peninsula (modern Spain, Portugal and Gibraltar).

With the patronage of the caliphs and the prestige of its liturgical status, Arabic rapidly became one of the world's main literary languages. Its spread among the masses took much longer, however, as many (although not all) of the native populations outside the Arabian Peninsula only gradually abandoned their languages in favour of Arabic. As Bedouin tribes settled in conquered areas, it became the main language of not only central Arabia, but also Yemen,[21] the Fertile Crescent, and Egypt. Most of the Maghreb followed, particularly in the wake of the Banu Hilal's incursion in the 11th century, and Arabic became the native language of many inhabitants of al-Andalus. After the collapse of the Nubian kingdom of Dongola in the 14th century, Arabic began to spread south of Egypt into modern Sudan; soon after, the Beni Ḥassān brought Arabization to Mauritania. A number of South Arabian languages distinct from Arabic still survive, such as Soqotri, Mehri and Shehri which are mainly spoken in Socotra, Yemen and Oman, and are likely descendants of the languages spoken in the ancient kingdoms of Sheba, Magan, Ubar, Meluhha and Dilmun.

Meanwhile, Semitic languages were diversifying in Ethiopia and Eritrea, where, under heavy Cushitic influence, they split into a number of languages, including Amharic and Tigrinya. With the expansion of Ethiopia under the Solomonic dynasty, Amharic, previously a minor local language, spread throughout much of the country, replacing both Semitic (such as Gafat) and non-Semitic (such as Weyto) languages, and replacing Ge'ez as the principal literary language (though Ge'ez remains the liturgical language for Christians in the region); this spread continues to this day, with Qimant set to disappear in another generation.

Present situation

Arabic languages and dialects are currently the native languages of majorities from Mauritania to Oman, and from Iraq to the Sudan. Classical Arabic is the language of the Quran, it is also studied widely in the non-Arabic-speaking Muslim world. The Maltese language is genetically a descendant of the extinct Siculo-Arabic, a variety of Maghrebi Arabic formerly spoken in Sicily. The modern Maltese alphabet is based on the Latin script with the addition of some letters with diacritic marks and digraphs. Maltese is the only Semitic official language of a nation state within the European Union.

Wildly successful as second languages far beyond their numbers of contemporary first-language speakers, a few Semitic languages today are the base of the sacred literature of some of the world's great religions, including Islam (Arabic), Judaism (Hebrew and Aramaic), churches of Syriac Christianity (Syriac) and Ethiopian Christianity (Ge'ez). Millions learn these as a second language (or an archaic version of their modern tongues): many Muslims learn to read and recite the Qur'an and Jews speak and study Biblical Hebrew, the language of the Torah, Midrash, and other Jewish scriptures. Ethnic Assyrian followers of the Assyrian Church of the East, Chaldean Catholic Church, Ancient Church of the East, Assyrian Pentecostal Church, Assyrian Evangelical Church and Assyrian members of the Syriac Orthodox Church both speak Mesopotamian eastern Aramaic and use it also as a liturgical tongue. The language is also used liturgically by the primarily Arabic-speaking followers of the Maronite, Syriac Catholic Church and some Melkite Christians. Arabic itself is the main liturgical language of Byzantine-rite Orthodox Christians in the Middle East, who compose the patriarchates of Antioch, Jerusalem and Alexandria. Mandaic is both spoken and used as a liturgical language by the Mandaeans.

Despite the ascendancy of Arabic in the Middle East, other Semitic languages still exist. Biblical Hebrew, long extinct as a colloquial language and in use only in Jewish literary, intellectual, and liturgical activity, was revived in spoken form at the end of the 19th century. Modern Hebrew is the main language of Israel, while remaining the language of liturgy and religious scholarship of Jews worldwide.

Several smaller ethnic groups, in particular the Assyrians, Kurdish Jews, and Gnostic Mandeans, continue to speak and write Mesopotamian Aramaic languages, particularly Neo-Aramaic languages descended from Syriac) in those areas roughly corresponding to Kurdistan (northern Iraq, northeast Syria, south eastern Turkey and northwestern Iran) and the Caucasus. Syriac language itself, a descendant of Eastern Aramaic languages (Mesopotamian Old Aramaic), is used also liturgically by the Syriac Christians throughout the area.

In Arab-dominated Yemen and Oman, on the southern rim of the Arabian Peninsula, a few tribes continue to speak Modern South Arabian languages such as Mahri and Soqotri. These languages differ greatly from both the surrounding Arabic dialects and from the (unrelated but previously thought to be related) languages of the Old South Arabian inscriptions.

Historically linked to the peninsular homeland of Old South Arabian, of which only one language, Razihi, remains, Ethiopia and Eritrea contain a substantial number of Semitic languages; the most widely spoken are Amharic in Ethiopia, Tigre in Eritrea, and Tigrinya in both. Amharic is the official language of Ethiopia. Tigrinya is a working language in Eritrea. Tigre is spoken by over one million people in the northern and central Eritrean lowlands and parts of eastern Sudan. A number of Gurage languages are spoken by populations in the semi-mountainous region of southwest Ethiopia, while Harari is restricted to the city of Harar. Ge'ez remains the liturgical language for certain groups of Christians in Ethiopia and in Eritrea.

Phonology

The phonologies of the attested Semitic languages are presented here from a comparative point of view. See Proto-Semitic language#Phonology for details on the phonological reconstruction of Proto-Semitic used in this article. This comparative approach is natural for the consonants, as sound correspondences among the consonants of the Semitic languages are very straightforward for a family of its time depth; for the vowels there are more subtleties.

Consonants

Each Proto-Semitic phoneme was reconstructed to explain a certain regular sound correspondence between various Semitic languages. Note that Latin letter values (italicized) for extinct languages are a question of transcription; the exact pronunciation is not recorded.

Most of the attested languages have merged a number of the reconstructed original fricatives, though South Arabian retains all fourteen (and has added a fifteenth from *p > f).

In Aramaic and Hebrew, all non-emphatic stops occurring singly after a vowel were softened to fricatives, leading to an alternation that was often later phonemicized as a result of the loss of gemination.

In languages exhibiting pharyngealization of emphatics, the original velar emphatic has rather developed to a uvular stop [q].

| Proto-Semitic | IPA | Arabic | Akkadian | Ugaritic | Phoenician | Hebrew | Aramaic | Ge'ez | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| written | standard | Classical [22] |

Old Arabic[23] |

written | Tiberian | Modern | |||||||||||

| *b | b | ب | b | /b/ | [b] | b | b | | b | ב | ḇ/b5 | /v/, /b/ | ב | ḇ/b5 | በ | /b/ | |

| *d | d | د | d | /d/ | [d] | d | d | | d | ד | ḏ/d5 | /d/ | ד | ḏ/d5 | ደ | /d/ | |

| *g | ɡ | ج | ǧ | /d͡ʒ/ | /ɟ/ | [g] | g | g | | g | ג | ḡ/g5 | /ɡ/ | ג | ḡ/g5 | ገ | /ɡ/ |

| *p | p | ف | f | /f/ | [pʰ] | p | p | | p | פ | p̄/p5 | /f/, /p/ | פ | p̄/p5 | ፈ | /f/ | |

| *t | t | ت | t | /t/ | [tʰ] | t | t | | t | ת | ṯ/t5 | /t/ | ת | ṯ/t5 | ተ | /t/ | |

| *k | k | ك | k | /k/ | [kʰ] | k | k | | k | כ | ḵ/k5 | /χ/, /k/ | כ | ḵ/k5 | ከ | /k/ | |

| *ṭ | tʼ | ط | ṭ | /tˤ/ | *ṭ | ṭ | ṭ | | ṭ | ט | ṭ | /t/ | ט | ṭ | ጠ | /tʼ/ | |

| *ḳ | kʼ | ق | q | /q/ | *ḳ | q | ḳ | | q | ק | q | /k/ | ק | q | ቀ | /kʼ/ | |

| *ḏ | ð / d͡ð | ذ | ḏ | /ð/ | [ð] | z | ḏ > d | | z | ז | z | /z/ | ז3/ד | ḏ3/d | ዘ | /z/ | |

| *z | z / d͡z | ز | z | /z/ | [z] | z | ז | z | |||||||||

| *ṯ | θ / t͡θ | ث | ṯ | /θ/ | [θ] | š | ṯ | | š | שׁ | š | /ʃ/ | ש3/ת | ṯ3/t | ሰ | /s/ | |

| *š | ʃ / t͡ʃ | س | s | /s/ | [s] | š | שׁ | š | |||||||||

| *ś | ɬ / t͡ɬ | ش | š | /ʃ/ | /ɕ/ | [ɬ] | שׂ1 | ś1 | /s/ | שׂ3/ס | ś3/s | ሠ | /ɬ/ | ||||

| *s | s / t͡s | س | s | /s/ | [s] | s | s | | s | ס | s | ס | s | ሰ | /s/ | ||

| *ṱ | θʼ / t͡θʼ | ظ | ẓ | /ðˤ/ | *ṱ | ṣ | q > ḡ | | ṣ | צ | ṣ | /ts/ | צ3/ט | ṯʼ 3/ṭ | ጸ | /tsʼ/ | |

| *ṣ | sʼ / t͡sʼ | ص | ṣ | /sˤ/ | *ṣ | ṣ | צ | ṣ | |||||||||

| *ṣ́ | ɬʼ / t͡ɬʼ | ض | ḍ | /dˤ/ | /ɮˤ/ | *ṣ́ | ק3/ע | *ġʼ 3/ʻ | ፀ | /ɬʼ/ | |||||||

| *ġ | ɣ~ʁ | غ | ḡ | /ɣ~ʁ/ | /ʁ/ | [ɣ] | – | ḡ,ʻ | | /ʕ/ | ע2 | ʻ2 | /ʔ/, - | ע3 | ḡ3/ʻ | ዐ | /ʕ/ |

| *ʻ | ʕ | ع | ʻ | /ʕ/ | [ʕ] | -4 | ʻ | ע | ʻ | ||||||||

| *ʼ | ʔ | ء | ʼ | /ʔ/ | [ʔ] | – | ʼ | | /ʔ/ | א | ʼ | /ʔ/, - | א | ʼ | አ | /ʔ/ | |

| *ḫ | x~χ | خ | ḫ | /x~χ/ | /χ/ | [x] | ḫ | ḫ | | ḥ | ח2 | ḥ2 | /χ/ | ח3 | ḫ3/ḥ | ኀ | /χ/ |

| *ḥ | ħ | ح | ḥ | /ħ/ | [ħ] | -4 | ḥ | ח | ḥ | ሐ | /ħ/ | ||||||

| *h | h | ه | h | /h/ | [h] | – | h | | h | ה | h | /h/, - | ה | h | ሀ | /h/ | |

| *m | m | م | m | /m/ | [m] | m | m | | m | מ | ṭ | /m/ | מ | m | መ | /m/ | |

| *n | n | ن | n | /n/ | [n] | n | n | | n | נ | n | /n/ | נ ר | n r |

ነ | /n/ | |

| *r | ɾ | ر | r | /r/ | [r] | r | r | | r | ר | r | /ʁ/ | ר | r | ረ | /r/ | |

| *l | ɬ | ل | l | /ɬ/ | [ɬ] | l | l | | l | ל | l | /ɬ/ | ל | l | ለ | /ɬ/ | |

| *y | j | ي | y | /j/ | [j] | y | y | | y | י | y | /j/ | י | y | የ | /j/ | |

| *w | w | و | w | /w/ | [w] | w | w y6 |

| w y6 |

ו י | w y6 |

/v/, /w/ /j/ |

ו י | w y6 |

ወ | /w/ | |

| Proto-Semitic | IPA | Arabic | Standard | Classical | Old | Akkadian | Ugaritic | Phoenician | Hebrew | Aramaic | Ge'ez | ||||||

Notes:

- Proto-Semitic *ś was still pronounced as [ɬ] in Biblical Hebrew, but no letter was available in the Phoenician alphabet, so the letter ש did double duty, representing both /ʃ/ and /ɬ/. Later on, however, /ɬ/ merged with /s/, but the old spelling was largely retained, and the two pronunciations of ש were distinguished graphically in Tiberian Hebrew as שׁ /ʃ/ vs. שׂ /s/ < /ɬ/.

- Biblical Hebrew as of the 3rd century BCE apparently still distinguished the phonemes ḡ /ʁ/ and ḫ /χ/, based on transcriptions in the Septuagint. As in the case of /ɬ/, no letters were available to represent these sounds, and existing letters did double duty: ח /χ/ /ħ/ and ע /ʁ/ /ʕ/. In both of these cases, however, the two sounds represented by the same letter eventually merged, leaving no evidence (other than early transcriptions) of the former distinctions.

- Although early Aramaic (pre-7th century BCE) had only 22 consonants in its alphabet, it apparently distinguished all of the original 29 Proto-Semitic phonemes, including *ḏ, *ṯ, *ṱ, *ś, *ṣ́, *ġ and *ḫ – although by Middle Aramaic times, these had all merged with other sounds. This conclusion is mainly based on the shifting representation of words etymologically containing these sounds; in early Aramaic writing, the first five are merged with z, š, ṣ, š, q, respectively, but later with d, t, ṭ, s, ʿ.[24][25] (Also note that due to begadkefat spirantization, which occurred after this merger, OAm. t > ṯ and d > ḏ in some positions, so that PS *t,ṯ and *d, ḏ may be realized as either of t, ṯ and d, ḏ respectively.) The sounds *ġ and *ḫ were always represented using the pharyngeal letters ʿ ḥ, but they are distinguished from the pharyngeals in the Demotic-script papyrus Amherst 63, written about 200 BCE.[26] This suggests that these sounds, too, were distinguished in Old Aramaic language, but written using the same letters as they later merged with.

- The earlier pharyngeals can be distinguished in Akkadian from the zero reflexes of *h, *ʔ by e-coloring adjacent *a, e.g. pS *ˈbaʕal-um 'owner, lord' > Akk. bēlu(m).[27]

- Hebrew and Aramaic underwent begadkefat spirantization at a certain point, whereby the stop sounds /b ɡ d k p t/ were softened to the corresponding fricatives [v ɣ ð x f θ] (written ḇ ḡ ḏ ḵ p̄ ṯ) when occurring after a vowel and not geminated. This change probably happened after the original Old Aramaic phonemes /θ, ð/ disappeared in the 7th century BCE,[28] and most likely occurred after the loss of Hebrew /χ, ʁ/ c. 200 BCE.[nb 1] It is known to have occurred in Hebrew by the 2nd century.[29] After a certain point this alternation became contrastive in word-medial and final position (though bearing low functional load), but in word-initial position they remained allophonic.[30] In Modern Hebrew, the distinction has a higher functional load due to the loss of gemination, although only the three fricatives /v χ f/ are still preserved (the fricative /x/ is pronounced /χ/ in modern Hebrew). (The others are pronounced like the corresponding stops, apparently under the influence of later non-native speakers whose native European tongues lacked the sounds /ɣ ð θ/ as phonemes.)

- In the Northwest Semitic languages, */w/ became */j/ at the beginning of a word, e.g. Hebrew yeled "boy" < *wald (cf. Arabic walad).

- There is evidence of a rule of assimilation of /j/ to the following coronal consonant in pre-tonic position, shared by Hebrew, Phoenician and Aramaic[31]

- In Assyrian Neo-Aramaic, [ħ] is nonexistent. In general cases, the language would lack pharyngeal fricative [ʕ] (as heard in Ayin). However though, /ʕ/ is retained in educational speech, especially among Assyrian priests.[32]

In addition to those in the table, Modern Hebrew has introduced the new phonemes /tʃ/, /dʒ/, /ʒ/ through borrowings.

The following table shows the development of the various fricatives in Hebrew, Aramaic and Arabic through cognate words:

| Proto-Semitic | Hebrew | Aramaic | Arabic | Examples | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hebrew | Aramaic | Arabic | meaning | ||||

| */ð/ *ḏ | */z/ ז | */d/ ד | */ð/ ذ | זהב זָכָר |

דהב דכרא |

ذهب ذَكَر |

'gold' 'male' |

| */z/1 *z | */z/ ז | */z/ ز | מאזנים זמן |

מאזנין זמן |

موازين زمن |

'scale' 'time' | |

| */ʃ/ *š | */ʃ/ שׁ | */ʃ/ שׁ | */s/ س | שׁנה שלום |

שׁנה שלם |

سنة سلام |

'year' 'peace' |

| */θ/ *ṯ | */t/ ת | */θ/ ث | שלוש שתים |

תלת תרין |

ثلاثة اثنان |

'three' 'two' | |

| */θʼ/1 *ṱ | */sˤ~ts/1 צ | */tʼ/ ט | */ðˤ/ ظ | צל צהרים |

טלה טהרא |

ظل ظهر |

'shadow' 'noon' |

| */ɬʼ/1 *ṣ́ | */ʕ/ ע | */dˤ/ ض | ארץ צחק |

ארע עחק |

أرض ضحك |

'land' 'laughed' | |

| */sʼ/1 *ṣ | */sʼ/ צ | */sˤ/ ص | צרח צבר |

צרח צבר |

صرخ صبر |

'shout' 'water melon like plant' | |

| */χ/ *ḫ | */ħ~χ/ ח | */ħ/ ח | */χ/ خ | חֲמִשָּׁה צרח |

חַמְשָׁה צרח |

خمسة صرخ |

'five' 'shout' |

| */ħ/ *ḥ | */ħ/ ح | מלח חלום |

מלח חלם |

ملح حلم |

'salt' 'dream' | ||

| */ʁ/ *ġ | */ʕ~ʔ/ ע | */ʕ/ ע | */ʁ/ غ | עורב מערב |

ערב מערב |

غراب غرب |

'raven' 'west' |

| */ʕ/ *ʻ | */ʕ/ ع | עבד שבע |

עבד שבע |

عبد سبعة |

'slave' 'seven' | ||

| */ɬ/ *ś | */s/ שׂ | */s/ שׂ | */ʃ/ ش | עשׂר | עשׂר | عشر | 'ten' |

- possibly affricated (/dz/ /tɬʼ/ /ʦʼ/ /tθʼ/ /tɬ/)

Vowels

Proto-Semitic vowels are, in general, harder to deduce due to the nonconcatenative morphology of Semitic languages. The history of vowel changes in the languages makes drawing up a complete table of correspondences impossible, so only the most common reflexes can be given:

| pS | Arabic | Aramaic | Hebrew | Ge'ez | Akkadian | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Classical | Modern | usually4 | /_C.ˈV | /ˈ_.1 | /ˈ_Cː2 | /ˈ_C.C3 | |||

| *a | a | a | a | ə | ā | a | ɛ | a | a, e, ē5 |

| *i | i | i | e, i, WSyr. ɛ |

ə | ē | e | ɛ, e | ə | i |

| *u | u | u | u, o | ə | ō | o | o | ə, ʷə6 | u |

| *ā | ā | ā | ā | ō[nb 2] | ā | ā, ē | |||

| *ī | ī | ī | ī | ī | ī | ī | |||

| *ū | ū | ū | ū | ū | ū | ū | |||

| *ay. | ay | ē, ay | BA, JA ay(i), ē, WSyr. ay/ī & ay/ē |

ayi, ay | ay, ē | ī | |||

| *aw. | aw | ō, aw | ō, WSyr. aw/ū |

ō, pausal ˈāwɛ |

ō | ū | |||

- in a stressed open syllable

- in a stressed closed syllable before a geminate

- in a stressed closed syllable before a consonant cluster

- when the proto-Semitic stressed vowel remained stressed

- pS *a,*ā > Akk. e,ē in the neighborhood of pS *ʕ,*ħ and before r.

- i.e. pS *g,*k,*ḳ,*χ > Ge'ez gʷ,kʷ,ḳʷ,χʷ / _u

Correspondence of sounds with other Afroasiatic languages

See table at Proto-Afroasiatic language#Consonant correspondences.

Grammar

The Semitic languages share a number of grammatical features, although variation – both between separate languages, and within the languages themselves – has naturally occurred over time.

Word order

The reconstructed default word order in Proto-Semitic is verb–subject–object (VSO), possessed–possessor (NG), and noun–adjective (NA). This was still the case in Classical Arabic and Biblical Hebrew, e.g. Classical Arabic ra'ā muħammadun farīdan. (literally "saw Muhammad Farid", Muhammad saw Farid). In the modern Arabic vernaculars, however, as well as sometimes in Modern Standard Arabic (the modern literary language based on Classical Arabic) and Modern Hebrew, the classical VSO order has given way to SVO. Modern Ethiopian Semitic languages follow a different word order: SOV, possessor–possessed, and adjective–noun; however, the oldest attested Ethiopian Semitic language, Ge'ez, was VSO, possessed–possessor, and noun–adjective.[34] Akkadian was also predominantly SOV.

Cases in nouns and adjectives

The proto-Semitic three-case system (nominative, accusative and genitive) with differing vowel endings (-u, -a -i), fully preserved in Qur'anic Arabic (see ʾIʿrab), Akkadian and Ugaritic, has disappeared everywhere in the many colloquial forms of Semitic languages. Modern Standard Arabic maintains such case distinctions, although they are typically lost in free speech due to colloquial influence. An accusative ending -n is preserved in Ethiopian Semitic.[35] The archaic Samalian dialect of Old Aramaic reflects a case distinction in the plural between nominative -ū and oblique -ī (compare the same distinction in Classical Arabic).[24][36] Additionally, Semitic nouns and adjectives had a category of state, the indefinite state being expressed by nunation.

Number in nouns

Semitic languages originally had three grammatical numbers: singular, dual, and plural. Classical Arabic still has a mandatory dual (i.e. it must be used in all circumstances when referring to two entities), marked on nouns, verbs, adjectives and pronouns. Many contemporary dialects of Arabic still have a dual, as in the name for the nation of Bahrain (baħr "sea" + -ayn "two"), although it is marked only on nouns. It also occurs in Hebrew in a few nouns (šana means "one year", šnatayim means "two years", and šanim means "years"), but for those it is obligatory. The curious phenomenon of broken plurals – e.g. in Arabic, sadd "one dam" vs. sudūd "dams" – found most profusely in the languages of Arabia and Ethiopia, may be partly of proto-Semitic origin, and partly elaborated from simpler origins.

Verb aspect and tense

| Past | Present Indicative | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | |||||

| 1st | katab-tu | كَتَبْتُ | ʼa-ktub-u | أَكْتُبُ | |

| 2nd | masculine | katab-ta | كَتَبْتَ | ta-ktub-u | تَكْتُبُ |

| feminine | katab-ti | كَتَبْتِ | ta-ktub-īna | تَكْتُبِينَ | |

| 3rd | masculine | katab-a | كَتَبَ | ya-ktub-u | يَكْتُبُ |

| feminine | katab-at | كَتَبَتْ | ta-ktub-u | تَكْتُبُ | |

| Dual | |||||

| 2nd | masculine & feminine |

katab-tumā | كَتَبْتُمَا | ta-ktub-āni | تَكْتُبَانِ |

| 3rd | masculine | katab-ā | كَتَبَا | ya-ktub-āni | يَكْتُبَانِ |

| feminine | katab-atā | كَتَبَتَا | ta-ktub-āni | تَكْتُبَانِ | |

| Plural | |||||

| 1st | katab-nā | كَتَبْنَا | na-ktub-u | نَكْتُبُ | |

| 2nd | masculine | katab-tum | كَتَبْتُمْ | ta-ktub-ūna | تَكْتُبُونَ |

| feminine | katab-tunna | كَتَبْتُنَّ | ta-ktub-na | تَكْتُبْنَ | |

| 3rd | masculine | katab-ū | كَتَبُوا | ya-ktub-ūna | يَكْتُبُونَ |

| feminine | katab-na | كَتَبْنَ | ya-ktub-na | يَكْتُبْنَ | |

All Semitic languages show two quite distinct styles of morphology used for conjugating verbs. Suffix conjugations take suffixes indicating the person, number and gender of the subject, which bear some resemblance to the pronominal suffixes used to indicate direct objects on verbs ("I saw him") and possession on nouns ("his dog"). So-called prefix conjugations actually takes both prefixes and suffixes, with the prefixes primarily indicating person (and sometimes number and/or gender), while the suffixes (which are completely different from those used in the suffix conjugation) indicate number and gender whenever the prefix does not mark this. The prefix conjugation is noted for a particular pattern of ʔ- t- y- n- prefixes where (1) a t- prefix is used in the singular to mark the second person and third-person feminine, while a y- prefix marks the third-person masculine; and (2) identical words are used for second-person masculine and third-person feminine singular. The prefix conjugation is extremely old, with clear analogues in nearly all the families of Afroasiatic languages (i.e. at least 10,000 years old). The table on the right shows examples of the prefix and suffix conjugations in Classical Arabic, which has forms that are close to Proto-Semitic.

In Proto-Semitic, as still largely reflected in East Semitic, prefix conjugations are used both for the past and the non-past, with different vocalizations. Cf. Akkadian niprus "we decided" (preterite), niptaras "we have decided" (perfect), niparras "we decide" (non-past or imperfect), vs. suffix-conjugated parsānu "we are/were/will be deciding" (stative). Some of these features, e.g. gemination indicating the non-past/imperfect, are generally attributed to Afroasiatic. According to Hetzron,[37] Proto-Semitic had an additional form, the jussive, which was distinguished from the preterite only by the position of stress: the jussive had final stress while the preterite had non-final (retracted) stress.

The West Semitic languages significantly reshaped the system. The most substantial changes occurred in the Central Semitic languages (the ancestors of modern Hebrew, Arabic and Aramaic). Essentially, the old prefix-conjugated jussive and/or preterite became a new non-past (or imperfect), while the stative became a new past (or perfect), and the old prefix-conjugated non-past (or imperfect) with gemination was discarded. New suffixes were used to mark different moods in the non-past, e.g. Classical Arabic -u (indicative), -a (subjunctive), vs no suffix (jussive). (It is not generally agreed whether the systems of the various Semitic languages are better interpreted in terms of tense, i.e. past vs. non-past, or aspect, i.e. perfect vs. imperfect.) However, in Hebrew, elements of the old system survived alongside the new system for a while, in forms known as the waw-consecutive and marked with a prefixed w-. The South Semitic languages show a system somewhere between the East and Central Semitic languages.

Later languages show further developments. In the modern varieties of Arabic, for example, the old mood suffixes were dropped, and new mood prefixes developed (e.g. bi- for indicative vs. no prefix for subjunctive in many varieties). In the extreme case of Neo-Aramaic, the verb conjugations have been entirely reworked under Iranian influence.

Morphology: triliteral roots

All Semitic languages exhibit a unique pattern of stems called Semitic roots consisting typically of "triliteral", or 3-consonant consonantal roots (2- and 4-consonant roots also exist), from which nouns, adjectives, and verbs are formed in various ways: e.g. by inserting vowels, doubling consonants, lengthening vowels, and/or adding prefixes, suffixes, or infixes.

For instance, the root k-t-b, (dealing with "writing" generally) yields in Arabic:

- kataba كَتَبَ or كتب "he wrote" (masculine)

- katabat كَتَبَت or كتبت "she wrote" (feminine)

- katabtu كَتَبْتُ or كتبت "I wrote" (f and m)

- kutiba كُتِبَ or كتب "it was written" (masculine)

- kutibat كُتِبَت or كتبت "it was written" (feminine)

- katabū كَتَبُوا or كتبوا "they wrote" (masculine)

- katabna كَتَبْنَ or كتبن "they wrote" (feminine)

- katabnā كَتَبْنَا or كتبنا "we wrote" (f and m)

- yaktub(u) يَكْتُب or يكتب "he writes" (masculine)

- taktub(u) تَكْتُب or تكتب "she writes" (feminine)

- naktub(u) نَكْتُب or نكتب "we write" (f and m)

- aktub(u) أَكْتُب or أكتب "I write" (f and m)

- yuktab(u) يُكْتَب or يكتب "being written" (masculine)

- tuktab(u) تُكتَب or تكتب "being written" (feminine)

- yaktubūn(a) يَكْتُبُونَ or يكتبون "they write" (masculine)

- yaktubna يَكْتُبْنَ or يكتبن "they write" (feminine)

- taktubna تَكْتُبْنَ or تكتبن "you write" (feminine)

- yaktubān(i) يَكْتُبَانِ or يكتبان "they both write" (masculine) (for 2 males)

- taktubān(i) تَكْتُبَانِ or تكتبان "they both write" (feminine) (for 2 females)

- kātaba كاتَبَ or كاتب "he exchanged letters (with sb.)"

- yukātib(u) ##### or يكاتب "he exchanges (with sb.)"

- yatakātabūn(a) يَتَكَاتَبُونَ or يتكاتبون "they write to each other" (masculine)

- iktataba اِكْتَتَبَ or اكتتب "he is registered" (intransitive) or "he contributed (a money quantity to sth.)" (ditransitive) (the first t is part of a particular verbal transfix, not part of the root)

- istaktaba اِسْتَكْتَبَ or استكتب "to cause to write (sth.)"

- kitāb كِتَاب or كتاب "book" (the hyphen shows end of stem before various case endings)

- kutub كُتُب or كتب "books" (plural)

- kutayyib كُتَيِّب or كتيب "booklet" (diminutive)

- kitābat كِتَابَة or كتابة "writing"

- kātib كاتِب or كاتب "writer" (masculine)

- kātibat كاتِبة or كاتبة "writer" (feminine)

- kātibūn(a) كاتِبونَ or كاتبون "writers" (masculine)

- kātibāt كاتِبات or كاتبات "writers" (feminine)

- kuttāb كُتاب or كتاب "writers" (broken plural)

- katabat كَتَبَة or كتبة "clerks" (broken plural)

- maktab مَكتَب or مكتب "desk" or "office"

- makātib مَكاتِب or مكاتب "desks" or "offices"

- maktabat مَكتَبة or مكتبة "library" or "bookshop"

- maktūb مَكتوب or مكتوب "written" (participle) or "postal letter" (noun)

- katībat كَتيبة or كتيبة "squadron" or "document"

- katā’ib كَتائِب or كتائب "squadrons" or "documents"

- iktitāb اِكتِتاب or اكتتاب "registration" or "contribution of funds"

- muktatib مُكتَتِب or مكتتب "subscription"

- istiktāb اِستِكتاب or استكتاب "causing to write"

and the same root in Hebrew:

- kāṯaḇti כתבתי "I wrote"

- kāṯaḇtā כתבת "you (m) wrote"

- kāṯaḇ כתב "he wrote"

- kattāḇ כתב "reporter" (m)

- katteḇeṯ כתבת "reporter" (f)

- kattāḇā כתבה "article" (plural kattāḇōṯ כתבות)

- miḵtāḇ מכתב "postal letter" (plural miḵtāḇīm מכתבים)

- miḵtāḇā מכתבה "writing desk" (plural miḵtāḇōṯ מכתבות)

- kəṯōḇeṯ כתובת "address" (plural kəṯōḇōṯ כתובות)

- kəṯāḇ כתב "handwriting"

- kāṯūḇ כתוב "written" (f kəṯūḇā כתובה)

- hiḵtīḇ הכתיב "he dictated" (f hiḵtīḇā הכתיבה)

- hiṯkattēḇ התכתב "he corresponded (f hiṯkattəḇā התכתבה)

- niḵtaḇ נכתב "it was written" (m)

- niḵtəḇā נכתבה "it was written" (f)

- kəṯīḇ כתיב "spelling" (m)

- taḵtīḇ תכתיב "prescript" (m)

- məḵuttāḇ מכתב "addressee" (meḵutteḇeṯ מכתבת f)

- kəṯubbā כתובה "ketubah (a Jewish marriage contract)" (f)

In Tigrinya and Amharic, this root survives only in the noun kitab, meaning "amulet", and the verb "to vaccinate". Ethiopic-derived languages use different roots for things that have to do with writing (and in some cases counting) primitive root: ṣ-f and trilateral root stems: m-ṣ-f, ṣ-h-f, and ṣ-f-r are used. This roots also exists in other Semitic languages like (Hebrew: sep̄er "book", sōp̄er "scribe", mispār "number" and sippūr "story"). (this root also exists in Arabic and is used to form words with a close meaning to "writing", such as ṣaḥāfa "journalism", and ṣaḥīfa "newspaper" or "parchment"). Verbs in other non-Semitic Afroasiatic languages show similar radical patterns, but more usually with biconsonantal roots; e.g. Kabyle afeg means "fly!", while affug means "flight", and yufeg means "he flew" (compare with Hebrew, where hap̄lēḡ means "set sail!", hap̄lāḡā means "a sailing trip", and hip̄līḡ means "he sailed", while the unrelated ʕūp̄, təʕūp̄ā and ʕāp̄ pertain to flight).

Independent personal pronouns

| English | Proto-Semitic | Akkadian | Arabic | Ge'ez | Hebrew | Aramaic | Syriac | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| standard | vernaculars | |||||||

| I | *ʔanāku,[nb 3] *ʔaniya | anāku | أنا ʔanā | ana, āni, āna, ānig | ʔana | אנכי, אני ʔānōḵī, ʔănī | אנא ʔanā | ānā |

| You (sg., masc.) | *ʔanka > *ʔanta | atta | أنت ʔanta | inta, inti, int, (i)nta | ʔánta | אתה ʔattā | אנת ʔantā | āt, āty, āten |

| You (sg., fem.) | *ʔanti | atti | أنت ʔanti | inti, init (i)nti,intch | ʔánti | את ʔatt | אנת ʔanti | āt, āty, āten |

| He | *suʔa | šū | هو huwa | huwwa, huwwe | wəʔətu | הוא hū | הוא hu | owā |

| She | *siʔa | šī | هي hiya | hiyya, hiyye | yəʔəti | היא hī | היא hi | ayā |

| We | *niyaħnū, *niyaħnā | nīnu | نحن naħnu | (i)ħna, niħna | nəħnā | אנו, אנחנו ʔānū, ʔănaħnū | נחנא náħnā | axnan |

| Ye (dual) | *ʔantunā | أنتما ʔantumā | ||||||

| They (dual) | *sunā[nb 4] | *sunī(ti) | هما humā | |||||

| Ye (pl., masc.) | *ʔantunū | attunu | أنتم ʔantum | intu, intum, (i)ntūma | ʔantəmu | אתם ʔattem | אנתן ʔantun | axtōxūn |

| Ye (pl., fem.) | *ʔantinā | attina | أنتنّ ʔantunna | ʔantən | אתן ʔatten | אנתן ʔanten | axtōxūn | |

| They (masc.) | *sunū | šunu | هم hum | hum(ma), hinne, hūma | ʔəmuntu | הם, המה hēm, hēmmā | הנן hinnun | eni |

| They (fem.) | *sinā | šina | هنّ hunna | ʔəmāntu | הן, הנה hēn, hēnnā | הנן hinnin | eni | |

Cardinal numerals

| English | Proto-Semitic[38] | IPA | Arabic | Hebrew | Tigrinya | Sabaean | Syriac |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| One | *ʼaḥad-, *ʻišt- | ʔaħad, ʔiʃt | واحد، أحد waːħid-, ʔaħad- | אחד ʼeḥáḏ ʔeˈχad | ħade | ʔḥd | xā |

| Two | *ṯin-ān (nom.), *ṯin-ayn (obl.), *kilʼ- | θinaːn, θinajn, kilʔ | اثنان iθn-āni (nom.), اثنين iθn-ajni (obj.), اثنتان fem. iθnat-āni, اثنتين iθnat-ajni | שנים šənáyim ˈʃn-ajim, fem. שתים šətáyim ˈʃt-ajim | kelete | *ṯny | treh |

| Three | *śalāṯ- > *ṯalāṯ-[nb 5] | ɬalaːθ > θalaːθ | ثلاث θalaːθ- | fem. שלוש šālṓš ʃaˈloʃ | seleste (Ge'ez śälas) | *ślṯ | ṭlā |

| Four | *ʼarbaʻ- | ʔarbaʕ | أربع ʔarbaʕ- | fem. ארבע ʼárbaʻ ˈʔaʁba | arbaʕte | *ʼrbʻ | arpā |

| Five | *ḫamš- | χamʃ | خمس χams- | fem. חמש ḥā́mēš ˈχameʃ | ħamuʃte | *ḫmš | xamšā |

| Six | *šidṯ-[nb 6] | ʃidθ | ستّ sitt- (ordinal سادس saːdis-) | fem. שש šēš ʃeʃ | ʃduʃte | *šdṯ/šṯ | ëštā |

| Seven | *šabʻ- | ʃabʕ | سبع sabʕ- | fem. שבע šéḇaʻ ˈʃeva | ʃewʕate | *šbʻ | šowā |

| Eight | *ṯamāniy- | θamaːnij- | ثماني θamaːn-ij- | fem. שמונה šəmṓneh ʃˈmone | ʃemonte | *ṯmny/ṯmn | *tmanyā |

| Nine | *tišʻ- | tiʃʕ | تسع tisʕ- | fem. תשע tḗšaʻ ˈtejʃa | tʃʕate | *tšʻ | *učā |

| Ten | *ʻaśr- | ʕaɬr | عشر ʕaʃ(a)r- | fem. עשר ʻéśer ˈʔeseʁ | ʕaserte | *ʻśr | *uṣrā |

These are the basic numeral stems without feminine suffixes. Note that in most older Semitic languages, the forms of the numerals from 3 to 10 exhibit gender polarity (also called "chiastic concord" or reverse agreement), i.e. if the counted noun is masculine, the numeral would be feminine and vice versa.

Typology

Some early Semitic languages are speculated to have had weak ergative features.[39]

Common vocabulary

Due to the Semitic languages' common origin, they share many words and roots. Others differ. For example:

| English | Proto-Semitic | Akkadian | Arabic | Aramaic | Syriac | Hebrew | Ge'ez | Mehri | Maltese |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| father | *ʼab- | ab- | ʼab- | ʼaḇ-āʼ | bābā | ʼāḇ | ʼab | ḥa-yb | missier |

| heart | *lib(a)b- | libb- | lubb- | lebb-āʼ | lëbā | lëḇ(āḇ) | libb | ḥa-wbēb | qalb |

| house | *bayt- | bītu, bētu | bayt-, dar | bayt-āʼ | bētā | báyiṯ, bêṯ | bet | beyt, bêt | dar |

| peace | *šalām- | šalām- | salām- | šlām-āʼ | šlāmā | šālôm | salām | səlōm | sliem |

| tongue | *lišān-/*lašān- | lišān- | lisān- | leššān-āʼ | lišānā | lāšôn | lissān | əwšēn | ilsien |

| water | *may-/*māy- | mû (root *mā-/*māy-) | māʼ-/māy | mayy-āʼ | mēyā | máyim | māy | ḥə-mō | ilma |

Sometimes, certain roots differ in meaning from one Semitic language to another. For example, the root b-y-ḍ in Arabic has the meaning of "white" as well as "egg", whereas in Hebrew it only means "egg". The root l-b-n means "milk" in Arabic, but the color "white" in Hebrew. The root l-ḥ-m means "meat" in Arabic, but "bread" in Hebrew and "cow" in Ethiopian Semitic; the original meaning was most probably "food". The word medina (root: m-d-n) has the meaning of "metropolis" in Amharic, "city" in Arabic and Ancient Hebrew, and "State" in Modern Hebrew.

Of course, there is sometimes no relation between the roots. For example, "knowledge" is represented in Hebrew by the root y-d-ʿ, but in Arabic by the roots ʿ-r-f and ʿ-l-m and in Ethiosemitic by the roots ʿ-w-q and f-l-ṭ.

For more comparative vocabulary lists, see Wiktionary appendices:

Classification

There are six fairly uncontroversial nodes within the Semitic languages: East Semitic, Northwest Semitic, North Arabian, Old South Arabian (also known as Sayhadic), Modern South Arabian, and Ethiopian Semitic. These are generally grouped further, but there is ongoing debate as to which belong together. The classification based on shared innovations given below, established by Robert Hetzron in 1976 and with later emendations by John Huehnergard and Rodgers as summarized in Hetzron 1997, is the most widely accepted today. In particular, several Semiticists still argue for the traditional (partially nonlinguistic) view of Arabic as part of South Semitic, and a few (e.g. Alexander Militarev or the German-Egyptian professor Arafa Hussein Mustafa) see the South Arabian languages as a third branch of Semitic alongside East and West Semitic, rather than as a subgroup of South Semitic. Roger Blench notes that the Gurage languages are highly divergent and wonders whether they might not be a primary branch, reflecting an origin of Afroasiatic in or near Ethiopia. At a lower level, there is still no general agreement on where to draw the line between "languages" and "dialects" – an issue particularly relevant in Arabic, Aramaic, and Gurage – and the strong mutual influences between Arabic dialects render a genetic subclassification of them particularly difficult.

The Himyaritic language appears to have been Semitic, but is unclassified due to insufficient data.

- East Semitic

- Central Semitic

- South Semitic

- Western: Ethiopian Semitic and Old South Arabian

- Eastern: Modern South Arabian

Semitic-speaking peoples

The following is a list of some modern and ancient Semitic-speaking peoples and nations:

Central Semitic

- Ammonite speakers of Ammon

- Amorites – 20th century BCE

- Arabs

- Ancient North Arabian-speaking bedouins

- Arameans – 16th to 8th centuries BCE[40] / Akhlames (Ahlamu) 14th century BCE.[41]

- Canaanite-speaking nations of the early Iron Age:

- Chaldea – appeared in southern Mesopotamia c. 1000 BCE and eventually disappeared into the general Babylonian population.

- Edomites

- Hebrews/Israelites – founded the nation of Israel which later split into the Kingdoms of Israel and Judah. The remnants of these people became the Jews and the Samaritans.

- Maltese

- Mandaeans

- Moab

- Mhallami – Tiny minority of Syriac-Arameans who converted to secular Islam but retained Syriac identity

- Nabataeans

- Phoenicia – founded Mediterranean colonies including Tyre, Sidon and ancient Carthage. The remnants of these people became the modern inhabitants of Lebanon.

- Ugarit, 14th to 12th centuries BCE

- Nasrani (Syrian Christian)

East Semitic

- Akkadian Empire – ancient Semitic speakers moved into Mesopotamia in the fourth millennium BCE and settled among the local peoples of Sumer.[42][43] The remnants of these people became the modern Assyrian people (also known as Chaldo-Assyrians) of Iraq, Iran, south eastern Turkey and northeast Syria.

- Ebla – 23rd century BCE

South Semitic

- Kingdom of Aksum – 4th century BCE to 7th century CE

- Amhara people

- Argobba people

- Dahalic people

- Gurage people

- Harari people

- Mehri people

- Old South Arabian-speaking peoples

- Sabaeans of Yemen – 9th to 1st centuries BCE

- Silt'e people

- Tigrayans

- Tigre people

- Tigrinyas

- Zay people

Unknown

See also

Notes

- ↑ According to the generally accepted view, it is unlikely that begadkefat spirantization occurred before the merger of /χ, ʁ/ and /ħ, ʕ/, or else [x, χ] and [ɣ, ʁ] would have to be contrastive, which is cross-linguistically rare. However, Blau argues that it is possible that lenited /k/ and /χ/ could coexist even if pronounced identically, since one would be recognized as an alternating allophone (as apparently is the case in Nestorian Syriac). See Blau (2010:56).

- ↑ see Canaanite shift

- ↑ While some believe that *ʔanāku was an innovation in some branches of Semitic utilizing an "intensifying" *-ku, comparison to other Afro-Asiatic 1ps pronouns (e.g. Eg. 3nk, Coptic anak, anok, proto-Berber *ənakkʷ) suggests that this goes further back. (Dolgopolsky 1999, pp. 10–11.)

- ↑ The Akkadian form is from Sargonic Akkadian. Among the Semitic languages, there are languages with /i/ as the final vowel (this is the form in Mehri). For a recent discussion concerning the reconstruction of the forms of the dual pronouns, see Bar-Asher, Elitzur. 2009. "Dual Pronouns in Semitics and an Evaluation of the Evidence for their Existence in Biblical Hebrew," Ancient Near Eastern Studies 46: 32–49

- ↑ Lipiński, Edward, Semitic languages: outline of a comparative grammar. This root underwent regressive assimilation. This parallels the non-adjacent assimilation of *ś... > *š...š in proto-Canaanite or proto-North-West-Semitic in the roots *śam?š > *šamš 'sun' and *śur?š > *šurš 'root'. (Dolgopolsky pp. 61–62.) The form *ṯalāṯ- appears in most languages (e.g. Aramaic, Arabic, Ugaritic), but the original form ślṯ appears in the South Arabian languages, and a form with s < *ś (rather than š < *ṯ) appears in Akkadian.

- ↑ Lipiński, Edward, Semitic languages: outline of a comparative grammar. This root was also assimilated in various ways. For example, Hebrew reflects *šišš-, with total assimilation; Arabic reflects *šitt- in cardinal numerals, but less assimilated *šādiš- in ordinal numerals. Epigraphic South Arabian reflects original *šdṯ; Ugaritic has a form ṯṯ, in which the ṯ has been assimilated throughout the root.

References

- ↑ Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin; Bank, Sebastian, eds. (2016). "Semitic". Glottolog 2.7. Jena: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- ↑ Baasten 2003.

- ↑ Jonathan, Owens (2013). The Oxford Handbook of Arabic Linguistics. Oxford University Press. p. 2. ISBN 0199344094. Retrieved 18 February 2014.

- ↑ Amharic at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015)

- ↑ Tigrinya at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015)

- ↑ Modern Hebrew at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015)

- ↑ ^ Jump up to: a b Assyrian Neo-Aramaic at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015)

- ↑ Chaldean Neo-Aramaic at Ethnologue (14th ed., 2000).

- ↑ ^ Turoyo at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015)

- ↑ ^ Jump up to: a b c Maltese at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015)

- 1 2 3 4 Ruhlen, Merritt (1991), A Guide to the World's Languages: Classification, Stanford University Press, ISBN 9780804718943,

The other linguistic group to be recognized in the eighteenth century was the Semitic family. The German scholar Ludwig von Schlozer is often credited with having recognizes, and named, the Semitic family in 1781. But the affinity of Hebrew, Arabic, and Aramaic had been recognized for centuries by Jewish and Islamic scholars, and this knowledge was published in Western Europe as early as 1538 (see Postel 1538). Around 1700 Hiob Ludolf, who had written grammars of Geez and Amharic (both Ethiopic Semitic languages) in the seventeenth century, recognized the extension of the Semitic family into East Africa. Thus when von Schlozer named the family in 1781 he was merely recognizing genetic relationships that had been known for centuries. Three Semitic languages (Aramaic, Arabic, and Hebrew) were long familiar to Europeans both because of their geographic proximity and because the Bible was written in Hebrew and Aramaic.

- 1 2 3 4 Kiraz, George Anton (2001). Computational Nonlinear Morphology: With Emphasis on Semitic Languages. Cambridge University Press. p. 25. ISBN 9780521631969.

The term "Semitic" is borrowed from the Bible (Gene. x.21 and xi.10–26). It was first used by the Orientalist A. L. Schlözer in 1781 to designate the languages spoken by the Aramæans, Hebrews, Arabs, and other peoples of the Near East (Moscati et al., 1969, Sect. 1.2). Before Schlözer, these languages and dialects were known as Oriental languages.

- ↑ Baasten 2003, p. 67.

- 1 2 3 Kitto, John (1845). A Cyclopædia of Biblical Literature. London: W. Clowes and Sons. p. 192.

That important family of languages, of which the Arabic is the most cultivated and most widely-extended branch, has long wanted an appropriate common name. The term Oriental languages, which was exclusively applied to it from the time of Jerome down to the end of the last century, and which is even now not entirely abandoned, must always have been an unscientific one, inasmuch as the countries in which these languages prevailed are only the east in respect to Europe; and when Sanskrit, Chinese, and other idioms of the remoter East were brought within the reach of our research, it became palpably incorrect. Under a sense of this impropriety, Eichhorn was the first, as he says himself (Allg. Bibl. Biblioth. vi. 772), to introduce the name Semitic languages, which was soon generally adopted, and which is the most usual one at the present day. [...] In modern times, however, the very appropriate designation Syro-Arabian languages has been proposed by Dr. Prichard, in his Physical History of Man. This term, [...] has the advantage of forming an exact counterpart to the name by which the only other great family of languages with which we are likely to bring the Syro-Arabian into relations of contrast or accordance, is now universally known—the Indo-Germanic. Like it, by taking up only the two extreme members of a whole sisterhood according to their geographical position when in their native seats, it embraces all the intermediate branches under a common band; and, like it, it constitutes a name which is not only at once intelligible, but one which in itself conveys a notion of that affinity between the sister dialects, which it is one of the objects of comparative philology to demonstrate and to apply.

- ↑ Baasten 2003, p. 68.

- 1 2 Baasten 2003, p. 69.

- ↑ Eichhorn 1794.

- ↑ "Semite". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 24 March 2014.

- ↑ ^ Averil Cameron,Peter Garnsey (1998). "The Cambridge Ancient History, Volume 13". p. 708.

- ↑ ^ Amir Harrak (1992). "The ancient name of Edessa". Journal of Near Eastern Studies 51 (3): 209–214. doi:10.1086/373553. JSTOR 545546.

- ↑ Nebes, Norbert, "Epigraphic South Arabian," in von Uhlig, Siegbert, Encyclopaedia Aethiopica (Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, 2005), pps.335.

- ↑ Watson, Janet (2002). The Phonology and Morphology of Arabic (PDF). New York: Oxford University Press. p. 13.

- ↑ Al-Jallad, Ahmad (2015). An Outline of the Grammar of the Safaitic Inscriptions. BRILL. p. 48.

- 1 2 "Old Aramaic (c. 850 to c. 612 BCE)". Retrieved 2011-08-22.

- ↑ "LIN325: Introduction to Semitic Languages. Common Consonant Changes" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2006-08-21. Retrieved 2006-06-25.

- ↑ Kaufman, Stephen (1997), "Aramaic", in Hetzron, Robert, The Semitic Languages, Routledge, pp. 117–119.

- ↑ Dolgopolsky 1999, p. 35.

- ↑ Dolgopolsky (1999:72)

- ↑ Dolgopolsky (1999:73)

- ↑ Blau (2010:78–81)

- ↑ Garnier, Romain; Jacques, Guillaume (2012). "A neglected phonetic law: The assimilation of pretonic yod to a following coronal in North-West Semitic". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies. 75.1: 135–145. doi:10.1017/s0041977x11001261.

- ↑ Brock, Sebastian (2006). An Introduction to Syriac Studies. Piscataway, NJ: Gorgias Press. ISBN 1-59333-349-8.

- ↑ Dolgopolsky 1999, pp. 85–86.

- ↑ Approaches to Language Typology by Masayoshi Shibatani and Theodora Bynon, page 157

- ↑ Moscati, Sabatino (1958). "On Semitic Case-Endings". Journal of Near Eastern Studies. 17 (2): 142–43. doi:10.1086/371454. "In the historically attested Semitic languages, the endings of the singular noun-flexions survive, as is well known, only partially: in Akkadian and Arabic and Ugaritic and, limited to the accusative, in Ethiopic.

- ↑ Hetzron, Robert (1997). The Semitic Languages. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-05767-7., page 123

- ↑ Robert Hetzron. "Biblical Hebrew" in The World's Major Languages.

- ↑ Weninger, Stefan (2011). "Reconstructive Morphology". In Semitic languages: an international handbook, Stefan Weninger, ed. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter. P. 166.

- ↑ Müller, Hans-Peter (1995). "Ergative Constructions In Early Semitic Languages". Journal of Near Eastern Studies. 54: 261–271. doi:10.1086/373769. JSTOR 545846..

- ↑ "Aramaean – Britannica Online Encyclopedia". Britannica.com. Retrieved 2013-01-27.

- ↑ "Akhlame – Britannica Online Encyclopedia". Britannica.com. Retrieved 2013-01-27.

- ↑ "Mesopotamian religion – Britannica Online Encyclopedia". Britannica.com. Retrieved 2013-01-27.

- ↑ "Akkadian language – Britannica Online Encyclopedia". Britannica.com. Retrieved 2013-01-27.

Additional reference literature

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- Baasten, Martin (2003). "A Note on the History of 'Semitic'". Hamlet on a Hill: Semitic and Greek Studies Presented to Professor T. Muraoka on the Occasion of His Sixty-fifth Birthday. Peeters Publishers. p. 57–73. ISBN 9789042912151.

- Bennett, Patrick R. 1998. Comparative Semitic Linguistics: A Manual. Eisenbrauns. ISBN 1-57506-021-3.

- Blau, Joshua (2010). Phonology and Morphology of Biblical Hebrew. Winona Lake, Indiana: Eisenbrauns. ISBN 1-57506-129-5.

- Dolgopolsky, Aron (1999). From Proto-Semitic to Hebrew. Milan: Centro Studi Camito-Semitici di Milano.

- Eichhorn, Johann Gottfried (1794). Allgemeine Bibliothek der biblischen Literatur. 6. p. 772–776.

- Bergsträsser, Gotthelf. 1995. Introduction to the Semitic Languages: Text Specimens and Grammatical Sketches. Translated by Peter T. Daniels. Winona Lake, Ind. : Eisenbrauns. ISBN 0-931464-10-2.

- Garbini, Giovanni. 1984. Le lingue semitiche: studi di storia linguistica. Naples: Istituto Orientale.

- Garbini, Giovanni; Durand, Olivier. 1995. Introduzione alle lingue semitiche. Paideia: Brescia 1995.

- Goldenberg, Gideon. 2013. Semitic Languages: Features, Structures, Relations, Processes. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-964491-9.

- Hetzron, Robert (ed.). 1997. The Semitic Languages. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-05767-1. (For family tree, see p. 7).

- Lipinski, Edward. 2001. Semitic Languages: Outlines of a Comparative Grammar. 2nd ed. Leuven: Orientalia Lovanensia Analecta. ISBN 90-429-0815-7

- Mustafa, Arafa Hussein. 1974. Analytical study of phrases and sentences in epic texts of Ugarit. (German title: Untersuchungen zu Satztypen in den epischen Texten von Ugarit). Dissertation. Halle-Wittenberg: Martin-Luther-University.

- Moscati, Sabatino. 1969. An introduction to the comparative grammar of the Semitic languages: phonology and morphology. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz.

- Ullendorff, Edward. 1955. The Semitic languages of Ethiopia: a comparative phonology. London: Taylor's (Foreign) Press.

- Wright, William; Smith, William Robertson. 1890. Lectures on the comparative grammar of the Semitic languages. Cambridge University Press 1890. [2002 edition: ISBN 1-931956-12-X]

External links

| Wikisource has the text of the 1905 New International Encyclopedia article Semitic Languages. |

- Semitic genealogical tree (as well as the Afroasiatic one), presented by Alexander Militarev at his talk "Genealogical classification of Afro-Asiatic languages according to the latest data" (at the conference on the 70th anniversary of Vladislav Illich-Svitych, Moscow, 2004; short annotations of the talks given there (Russian)

- Pattern-and-root inflectional morphology: the Arabic broken plural

- Ancient snake spell in Egyptian pyramid may be oldest Semitic inscription

- Swadesh vocabulary lists of Semitic languages (from Wiktionary's Swadesh-list appendix)