Aphasia

| Aphasia | |

|---|---|

| Classification and external resources | |

| Pronunciation | /əˈfeɪʒə/, /əˈfeɪziə/ or /eɪˈfeɪziə/ |

| Specialty | Neurology, Psychiatry |

| ICD-10 | F80.0-F80.2, R47.0 |

| ICD-9-CM | 315.31, 784.3, 438.11 |

| DiseasesDB | 4024 |

| MedlinePlus | 003204 |

| eMedicine | neuro/437 |

| MeSH | D001037 |

| Dysphasia | |

|---|---|

| Classification and external resources | |

| Specialty | Neurology |

| ICD-10 | F80.1, F80.2, R47.0 |

| ICD-9-CM | 438.12, 784.5 |

Aphasia is an inability to comprehend and formulate language because of damage to specific brain regions.[1] This damage is typically caused by a cerebral vascular accident (stroke), or head trauma, however these are not the only possible causes. To be diagnosed with aphasia, a person's speech or language must be significantly impaired in one (or several) of the four communication modalities following acquired brain injury or have significant decline over a short time period (progressive aphasia). The four communication modalities are auditory comprehension, verbal expression, reading and writing, and functional communication.

The difficulties of people with aphasia can range from occasional trouble finding words to losing the ability to speak, read, or write; intelligence, however, is unaffected.[2] Expressive language and receptive language can both be affected as well. Aphasia also affects visual language such as sign language.[1] In contrast, the use of formulaic expressions in everyday communication is often preserved.[3] One prevalent deficit in the aphasias is anomia, which is a deficit in word finding ability.[4]

The term "aphasia" implies that one or more communication modalities have been damaged and are therefore functioning incorrectly. Aphasia does not refer to damage to the brain that results in motor or sensory deficits, as it is not related to speech (which is the verbal aspect of communicating) but rather the individual's language. An individual's "language" is the socially shared set of rules as well as the thought processes that go behind verbalized speech. It is not a result of a more peripheral motor or sensory difficulty, such as paralysis affecting the speech muscles or a general hearing impairment.

Aphasia is from Greek a- ("without") + phásis (φάσις, "speech"). The word aphasia comes from the word ἀφασία aphasia, in Ancient Greek, which means[5] "speechlessness",[6] derived from ἄφατος aphatos, "speechless"[7] from ἀ- a-, "not, un" and φημί phemi, "I speak".

Signs and symptoms

People with aphasia may experience any of the following behaviors due to an acquired brain injury, although some of these symptoms may be due to related or concomitant problems such as dysarthria or apraxia and not primarily due to aphasia. Aphasia symptoms can vary based on the location of damage in the brain. Signs and symptoms may or may not be present in individuals with aphasia and may vary in severity and level of disruption to communication.[8] Often those with aphasia will try to hide their inability to name objects by using words like thing. So when asked to name a pencil they may say it is a thing used to write.[9]

- Inability to comprehend language

- Inability to pronounce, not due to muscle paralysis or weakness

- Inability to speak spontaneously

- Inability to form words

- Inability to name objects (anomia)

- Poor enunciation

- Excessive creation and use of personal neologisms

- Inability to repeat a phrase

- Persistent repetition of one syllable, word, or phrase (stereotypies)

- Paraphasia (substituting letters, syllables or words)

- Agrammatism (inability to speak in a grammatically correct fashion)

- Dysprosody (alterations in inflexion, stress, and rhythm)

- Incomplete sentences

- Inability to read

- Inability to write

- Limited verbal output

- Difficulty in naming

- Speech disorder

- Speaking gibberish

- Inability to follow or understand simple requests

Related behaviors

Given the previously stated signs and symptoms the following behaviors are often seen in people with aphasia as a result of attempted compensation for incurred speech and language deficits:

- Self-repairs: Further disruptions in fluent speech as a result of mis-attempts to repair erred speech production.

- Speech disfluencies: Include previously mentioned disfluencies including repetitions and prolongations at the phonemic, syllable and word level presenting in pathological/ severe levels of frequency.

- Struggle in non-fluent aphasias: A severe increase in expelled effort to speak after a life where talking and communicating was an ability that came so easily can cause visible frustration.

- Preserved and automatic language: A behavior in which some language or language sequences that were used so frequently, prior to onset, they still possess the ability to produce them with more ease than other language post onset.[10]

Types

Acute aphasias

The following table summarizes some major characteristics of different acute aphasias:

| Type of aphasia | Repetition | Naming | Auditory comprehension | Fluency |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Receptive aphasia | mild–mod | mild–severe | defective | fluent paraphasic |

| Transcortical sensory aphasia | good | mod–severe | poor | fluent |

| Conduction aphasia | poor | mild | relatively good | fluent |

| Anomic aphasia | mild | mod–severe | mild | fluent |

| Expressive aphasia | mod–severe | mod–severe | mild difficulty | non-fluent, effortful, slow |

| Transcortical motor aphasia | good | mild–severe | relatively good | non-fluent |

| Global aphasia | severe | mod-severe | severe-profound | non-fluent |

| Mixed transcortical aphasia | moderate | poor | poor | non-fluent |

- Individuals with receptive aphasia may speak in long sentences that have no meaning, add unnecessary words, and even create new "words" (neologisms). For example, someone with receptive aphasia may say, "You know that smoodle pinkered and that I want to get him round and take care of him like you want before", meaning "The dog needs to go out so I will take him for a walk". They have poor auditory and reading comprehension, and fluent, but nonsensical, oral and written expression. Individuals with receptive aphasia usually have great difficulty understanding the speech of both themselves and others and are, therefore, often unaware of their mistakes. Receptive language deficits usually arise from lesions in the posterior portion of the left hemisphere at or near Wernicke's area.[11]

- Individuals with transcortical sensory aphasia, in principle the most general and potentially among the most complex forms of aphasia, may have similar deficits as in receptive aphasia, but their repetition ability may remain intact.

- Individuals with conduction aphasia have deficits in the connections between the speech-comprehension and speech-production areas. This might be caused by damage to the arcuate fasciculus, the structure that transmits information between Wernicke's area and Broca's area. Similar symptoms, however, can be present after damage to the insula or to the auditory cortex. Auditory comprehension is near normal, and oral expression is fluent with occasional paraphasic errors. Paraphasic errors include phonemic/literal or semantic/verbal. Repetition ability is poor.

- Individuals with anomic aphasia have difficulty with naming. The patients may have difficulties naming certain words, linked by their grammatical type (e.g., difficulty naming verbs and not nouns) or by their semantic category (e.g., difficulty naming words relating to photography but nothing else) or a more general naming difficulty. Patients tend to produce grammatic, yet empty, speech. Auditory comprehension tends to be preserved. Anomic aphasia is the aphasia presentation of tumors in the language zone; it is the aphasia presentation of Alzheimer's disease.[12]

- Individuals with expressive aphasia frequently speak short, meaningful phrases that are produced with great effort. Expressive aphasia is thus characterized as a nonfluent aphasia. Affected people often omit small words such as "is", "and", and "the". For example, a person with expressive aphasia may say, "Walk dog," which could mean "I will take the dog for a walk", "You take the dog for a walk" or even "The dog walked out of the yard". Individuals with expressive aphasia are able to understand the speech of others to varying degrees. Because of this, they are often aware of their difficulties and can become easily frustrated by their speaking problems.

- Individuals with transcortical motor aphasia have similar deficits as expressive aphasia, except repetition ability remains intact. Auditory comprehension is generally fine for simple conversations, but declines rapidly for more complex conversations. It is associated with right hemiparesis, meaning that there can be paralysis of the patient's right face and arm.

- Individuals with global aphasia have severe communication difficulties and will be extremely limited in their ability to speak or comprehend language. They may be totally nonverbal, and/or use only facial expressions and gestures to communicate. It is associated with right hemiparesis, meaning that there can be paralysis of the patient's right face and arm.

- Individuals with mixed transcortical aphasia have similar deficits as in global aphasia, but repetition ability remains intact.

Subcortical aphasias

- Subcortical aphasias characteristics and symptoms depend upon the site and size of subcortical lesion. Possible sites of lesions include the thalamus, internal capsule, and basal ganglia.

Causes

Aphasia is most often caused by stroke, but any disease or damage to the parts of the brain that control language can cause aphasia. Some of these can include brain tumors, traumatic brain injury, and progressive neurological disorders.[14] In rare cases, aphasia may also result from herpesviral encephalitis.[15] The herpes simplex virus affects the frontal and temporal lobes, subcortical structures, and the hippocampal tissue, which can trigger aphasia.[16] In acute disorders, such as head injury or stroke, aphasia usually develops quickly. When caused by brain tumor, infection, or dementia, it develops more slowly.[2][17][18]

There are two types of strokes: ischemic stroke and hemorrhagic stroke. An ischemic stroke happens when a person’s artery, which supplies blood to different areas of the brain, becomes blocked with a blood clot. This type of stroke happens 80% of the time. The blood clot may form in the blood vessel,l which is called a thrombus, or the blood clot can travel from somewhere else in the blood system that is called an embolus. A hemorrhagic stroke occurs when a blood vessel in the brain ruptures or bursts. Overall, people experience bleeding inside or around brain tissue. This type of stroke happens 20% of the time and is very serious. The most common causes of hemorrhagic stroke are weak vessels, traumatic injury, chronic high blood pressure hypertension, and an aneurysm.

Although all of the diseases listed above are potential causes, aphasia will generally only result when there is substantial damage to the left hemisphere (responsible for language function) of the brain, either the cortex (outer layer) and/or the underlying white matter.

Substantial damage to tissue anywhere within the region shown in blue on the figure below can potentially result in aphasia.[19] Aphasia can also sometimes be caused by damage to subcortical structures deep within the left hemisphere, including the thalamus, the internal and external capsules, and the caudate nucleus of the basal ganglia.[20][21] The area and extent of brain damage or atrophy will determine the type of aphasia and its symptoms.[2][17] A very small number of people can experience aphasia after damage to the right hemisphere only. It has been suggested that these individuals may have had an unusual brain organization prior to their illness or injury, with perhaps greater overall reliance on the right hemisphere for language skills than in the general population.[22][23]

Primary progressive aphasia (PPA), while its name can be misleading, is actually a form of dementia that has some symptoms closely related to several forms of aphasia. It is characterized by a gradual loss in language functioning while other cognitive domains are mostly preserved, such as memory and personality. PPA usually initiates with sudden word-finding difficulties in an individual and progresses to a reduced ability to formulate grammatically correct sentences (syntax) and impaired comprehension. The etiology of PPA is not due to a stroke, traumatic brain injury (TBI), or infectious disease; it is still uncertain what initiates the onset of PPA in those affected by it.[24]

Finally, certain chronic neurological disorders, such as epilepsy or migraine, can also include transient aphasia as a prodromal or episodic symptom.[25] Aphasia is also listed as a rare side-effect of the fentanyl patch, an opioid used to control chronic pain.[26][27]

Classification

Aphasia is best thought of as a collection of different disorders, rather than a single problem. Each individual with aphasia will present with their own particular combination of language strengths and weaknesses. Consequently, it is a major challenge just to document the various difficulties that can occur in different people, let alone decide how they might best be treated. Most classifications of the aphasias tend to divide the various symptoms into broad classes. A common approach is to distinguish between the fluent aphasias (where speech remains fluent, but content may be lacking, and the person may have difficulties understanding others), and the nonfluent aphasias (where speech is very halting and effortful, and may consist of just one or two words at a time).

However, no such broad-based grouping has proven fully adequate. There is a huge variation among patients within the same broad grouping, and aphasias can be highly selective. For instance, patients with naming deficits (anomic aphasia) might show an inability only for naming buildings, or people, or colors.[28]

It is important to note that there are typical difficulties with speech and language that come with normal aging as well. As we age language can become more difficult to process resulting in slowing of verbal comprehension, reading abilities and more likely word finding difficulties. With each of these though, unlike some aphasias, functionality within daily life remains intact.[29]

Classical-localizationist approaches

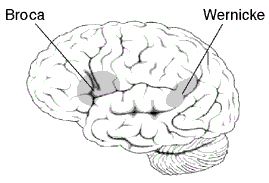

Localizationist approaches aim to classify the aphasias according to their major presenting characteristics and the regions of the brain that most probably gave rise to them.[30][31] Inspired by the early work of nineteenth century neurologists Paul Broca and Carl Wernicke, these approaches identify two major subtypes of aphasia and several more minor subtypes:

- Expressive aphasia (also known as "motor aphasia" or "Broca's aphasia"), which is characterized by halted, fragmented, effortful speech, but relatively well-preserved comprehension. Damage is typically in the anterior portion of the left hemisphere,[32] most notably Broca's area. Individuals with Broca's aphasia often have right-sided weakness or paralysis of the arm and leg, because the left frontal lobe is also important for body movement, particularly on the right side.

- Receptive aphasia (also known as "sensory aphasia" or "Wernicke's aphasia"), which is characterized by fluent speech, but marked difficulties understanding words and sentences. Although fluent, the speech may lack in key substantive words (nouns, verbs, adjectives), and may contain incorrect words or even nonsense words. This subtype has been associated with damage to the posterior left temporal cortex, most notably Wernicke's area. These individuals usually have no body weakness, because their brain injury is not near the parts of the brain that control movement.

- Conduction aphasia, where speech remains fluent, and comprehension is preserved, but the person may have disproportionate difficulty where repeating words or sentences. Damage typically involves the arcuate fasciculus and the left parietal region.[32]

- Transcortical motor aphasia and transcortical sensory aphasia, which are similar to Broca's and Wernicke's aphasia respectively, but the ability to repeat words and sentences is disproportionately preserved.

Recent classification schemes adopting this approach, such as the "Boston-Neoclassical Model",[30] also group these classical aphasia subtypes into two larger classes: the nonfluent aphasias (which encompasses Broca's aphasia and transcortical motor aphasia) and the fluent aphasias (which encompasses Wernicke's aphasia, conduction aphasia and transcortical sensory aphasia). These schemes also identify several further aphasia subtypes, including: anomic aphasia, which is characterized by a selective difficulty finding the names for things; and global aphasia, where both expression and comprehension of speech are severely compromised.

Many localizationist approaches also recognize the existence of additional, more "pure" forms of language disorder that may affect only a single language skill.[33] For example, in pure alexia, a person may be able to write but not read, and in pure word deafness, they may be able to produce speech and to read, but not understand speech when it is spoken to them.

Cognitive neuropsychological approaches

Although localizationist approaches provide a useful way of classifying the different patterns of language difficulty into broad groups, one problem is that a sizeable number of individuals do not fit neatly into one category or another.[34][35] Another problem is that the categories, particularly the major ones such as Broca's and Wernicke's aphasia, still remain quite broad. Consequently, even amongst individuals who meet the criteria for classification into a subtype, there can be enormous variability in the types of difficulties they experience.

Instead of categorizing every individual into a specific subtype, cognitive neuropsychological approaches aim to identify the key language skills or "modules" that are not functioning properly in each individual. A person could potentially have difficulty with just one module, or with a number of modules. This type of approach requires a framework or theory as to what skills/modules are needed to perform different kinds of language tasks. For example, the model of Max Coltheart identifies a module that recognizes phonemes as they are spoken, which is essential for any task involving recognition of words. Similarly, there is a module that stores phonemes that the person is planning to produce in speech, and this module is critical for any task involving the production of long words or long strings of speech. Once a theoretical framework has been established, the functioning of each module can then be assessed using a specific test or set of tests. In the clinical setting, use of this model usually involves conducting a battery of assessments,[36][37] each of which tests one or a number of these modules. Once a diagnosis is reached as to the skills/modules where the most significant impairment lies, therapy can proceed to treat these skills.

Progressive aphasias

Primary progressive aphasia (PPA) is a focal dementia that can be associated with progressive illnesses or dementia, such as frontotemporal dementia / Pick Complex Motor neuron disease, Progressive supranuclear palsy, and Alzheimer's disease, which is the gradual process of progressively losing the ability to think. Gradual loss of language function occurs in the context of relatively well-preserved memory, visual processing, and personality until the advanced stages. Symptoms usually begin with word-finding problems (naming) and progress to impaired grammar (syntax) and comprehension (sentence processing and semantics).<American Speech-Language-Hearing Association> People suffering from PPA may have difficulties comprehending what others are saying. They can also have difficulty trying to find the right words to make a sentence.[38][39][40] There are three classifications of Primary Progressive Aphasia : Progressive nonfluent aphasia (PNFA), Semantic Dementia (SD), and Logopenic progressive aphasia (LPA)[40][41]

Progressive Jargon Aphasia is a fluent or receptive aphasia in which the patient's speech is incomprehensible, but appears to make sense to them. Speech is fluent and effortless with intact syntax and grammar, but the patient has problems with the selection of nouns. Either they will replace the desired word with another that sounds or looks like the original one or has some other connection or they will replace it with sounds. As such, patients with jargon aphasia often use neologisms, and may perseverate if they try to replace the words they cannot find with sounds. Substitutions commonly involve picking another (actual) word starting with the same sound (e.g., clocktower - colander), picking another semantically related to the first (e.g., letter - scroll), or picking one phonetically similar to the intended one (e.g., lane - late).

Deaf aphasia

There have been many instances showing that there is a form of aphasia among deaf individuals. Sign language is, after all, a form of communication that has been shown to use the same areas of the brain as verbal forms of communication. Mirror neurons become activated when an animal is acting in a particular way or watching another individual act in the same manner. These mirror neurons are important in giving an individual the ability to mimic movements of hands. Broca's area of speech production has been shown to contain several of these mirror neurons resulting in significant similarities of brain activity between sign language and vocal speech communication. Facial communication is a significant portion of how animals interact with each other. Humans use facial movements to create, what other humans perceive, to be faces of emotions. While combining these facial movements with speech, a more full form of language is created which enables the species to interact with a much more complex and detailed form of communication. Sign language also uses these facial movements and emotions along with the primary hand movement way of communicating. These facial movement forms of communication come from the same areas of the brain. When dealing with damages to certain areas of the brain, vocal forms of communication are in jeopardy of severe forms of aphasia. Since these same areas of the brain are being used for sign language, these same, at least very similar, forms of aphasia can show in the Deaf community. Individuals can show a form of Wernicke's aphasia with sign language and they show deficits in their abilities in being able to produce any form of expressions. Broca's aphasia shows up in some patients, as well. These individuals find tremendous difficulty in being able to actually sign the linguistic concepts they are trying to express.[42]

Prevention

Following are some precautions that should be taken to avoid aphasia, by decreasing the risk of stroke, the main cause of aphasia:

- Exercising regularly

- Eating a healthy diet

- Keeping alcohol consumption low and avoiding tobacco use

- Controlling blood pressure[5]

Management

Most acute cases of aphasia recover some or most skills by working with a speech-language pathologist. This rehabilitation can take two or more years and is most effective when begun quickly. After the onset of Aphasia, there is approximately a six-month period of spontaneous recovery. During this time, the brain is attempting to recover and repair the damaged neurons. Therapy for Aphasia during this time facilitates an even greater level of recovery than if no intervention was given at this time.[43] Improvement varies widely, depending on the aphasia's cause, type, and severity. Recovery also depends on the patient's age, health, motivation, handedness, and educational level.[17]

There is no one treatment proven to be effective for all types of aphasias. The reason that there is no universal treatment for aphasia is because of the nature of the disorder and the various ways it is presented, as explained in the above sections. Aphasia is rarely exhibited identically, implying that treatment needs to be catered specifically to the individual. Studies have shown that, although there is no consistency on treatment methodology in literature, there is a strong indication that treatment in general has positive outcomes.[44] Therapy for aphasia ranges from increasing functional communication to improving speech accuracy, depending on the person's severity, needs and support of family and friends.[45] Group therapy allows individuals to work on their pragmatic and communication skills with other individuals with aphasia, which are skills that may not often be addressed in individual one-on-one therapy sessions. It can also help increase confidence and social skills in a comfortable setting.[46]

A multi-disciplinary team, including doctors (often a physician is involved, but more likely a clinical neuropsychologist will head the treatment team), physiotherapist, occupational therapist, speech-language pathologist, physical therapist, dietician, and social worker, work together in treating aphasia. For the most part, treatment relies heavily on repetition and aims to address language performance by working on task-specific skills. The primary goal is to help the individual and those closest to them adjust to changes and limitations in communication.[44]

Treatment techniques mostly fall under two approaches:

- Substitute Skill Model - an approach that uses an aid to help with spoken language, i.e. a writing board

- Direct Treatment Model - an approach that targets deficits with specific exercises[44]

Several treatment techniques include the following:

- Copy and Recall Therapy (CART) - repetition and recall of targeted words within therapy may strengthen orthographic representations and improve single word reading, writing, and naming[47]

- Visual Communication Therapy (VIC) - the use of index cards with symbols to represent various components of speech

- Visual Action Therapy (VAT) - typically treats individuals with global aphasia to train the use of hand gestures for specific items[48]

- Functional Communication Treatment (FCT) - focuses on improving activities specific to functional tasks, social interaction, and self-expression

- Promoting Aphasic's Communicative Effectiveness (PACE) - a means of encouraging normal interaction between patients and clinicians. In this kind of therapy the focus is on pragmatic communication rather than treatment itself. Patients are asked to communicate a given message to their therapists by means of drawing, making hand gestures or even pointing to an object[49]

- Melodic Intonation Therapy (MIT) - aims to use the intact melodic/prosodic processing skills of the right hemisphere to help cue retrieval of words and expressive language[50]

- Other - i.e. drawing as a way of communicating, trained conversation partners[44]

Semantic feature analysis (SFA) -a type of aphasia treatment that targets word-finding deficits. It is based on the theory that neural connections can strengthened by using using related words and phrases that are similar to the target word, to eventually activate the target word in the brain. SFA can be implemented in multiple forms such as verbally, written, using picture cards, etc. The SLP provides prompting questions to the individual with aphasia in order for the person to name the picture provided. [51] Studies show that SFA is an effective intervention for improving confrontational naming.[52]

Melodic Intonation Therapy is used to treat non-fluent aphasia and has proved to be effective in some cases.[53] However, there is still no evidence from randomized controlled trials confirming the efficacy of MIT in chronic aphasia. MIT is used to help people with aphasia vocalize themselves through speech song, which is then transferred as a spoken word. Good candidates for this therapy include left hemisphere stroke patients, non-fluent aphasias such as Broca's, good auditory comprehension, poor repetition and articulation, and good emotional stability and memory.[54] It has been hypothesized that MIT is effective because prosody and singing both rely on areas of the right hemisphere; it may be these right-hemisphere areas that are recruited for natural speech production after intensive training.[55] An alternative explanation is that the efficacy of MIT depends on neural circuits involved in the processing of rhythmicity and formulaic expressions (examples taken from the MIT manual: “I am fine,” “how are you?” or “thank you”); while rhythmic features associated with melodic intonation may engage primarily left-hemisphere subcortical areas of the brain, the use of formulaic expressions is known to be supported by right-hemisphere cortical and bilateral subcortical neural networks.[3][56]

More recently, computer technology has been incorporated into treatment options. A key indication for good prognosis is treatment intensity. A minimum of two–three hours per week has been specified to produce positive results.[57] The main advantage of using computers is that it can greatly increase intensity of therapy. These programs consist of a large variety of exercises and can be done at home in addition to face-to-face treatment with a therapist. However, since aphasia presents differently among individuals, these programs must be dynamic and flexible in order to adapt to the variability in impairments. Another barrier is the capability of computer programs to imitate normal speech and keep up with the speed of regular conversation. Therefore, computer technology seems to be limited in a communicative setting, however is effective in producing improvements in communication training.[57]

Intensity of treatment

The intensity of aphasia therapy is determined by the length of each session, total hours of therapy per week, and total weeks of therapy provided. There is no consensus about what “intense” aphasia therapy entails, or how intense therapy should be to yield the best outcomes. Overall, treatment is considered more intense when total therapy hours per week are increased, and on average, research suggests more intense therapy leads to better outcomes. For example, one study found that patients who were treated for 8.8 hours a week for 11.2 weeks progressed more than patients who were treated 2 hours a week for 22.9 weeks.[58] Results of another study corroborate these findings. The researchers found that patients who received intensive therapy of 100 treatment hours over 62 weeks scored higher on language measures than the control group who received less intensive therapy.[59] Therefore, although there is a general consensus that intense treatment encourages more improvement, there is not a straightforward definition of “intense” treatment.

Intensity of treatment should be individualized based on the recency of stroke, therapy goals, and other patient-specific characteristics such as age, size of lesion, overall health status, and motivation.[60][61] Each individual reacts differently to treatment intensity and is able to tolerate treatment at different times post-stroke.[62] Some patients cannot tolerate therapy directly after a stroke due to confusion or exhaustion, but may tolerate therapy better later. Intensity of treatment after a stroke should be dependent on the patient’s motivation, stamina, and tolerance for therapy.[62] Level of intensity also depends on therapy goals; for certain goals non-intensive therapy is more beneficial. For example, non-intensive therapy has been found to be more effective than intensive therapy when targeting naming accuracy in patients with anomia.[61] This is because more time in between sessions allows for rehearsal and reinforces long term learning.[61]

Intensity of therapy is also dependent on the recency of stroke. Patients react differently to intense treatment in the acute phase (0–3 months post stroke), sub-acute phase (3–6 months post stroke), or chronic phase (6+ months post stroke). Intensive therapy has been found to be effective for patients with nonfluent and fluent chronic aphasia, but less effective for patients with acute aphasia.[60][63] Patients with sub-acute aphasia also respond well to intensive therapy of 100 hours over 62 weeks. This suggests patients in the sub-acute phase can improve greatly in language and functional communication measures with intensive therapy compared to regular therapy.[59] Research suggests that intense treatment is most beneficial in the sub-acute or chronic phase, rather than directly post stroke.[59][60][63] More research needs to be done to examine the optimal time for providing intense therapy to all aphasic patients.[60]

Intensive therapy can be alternatively characterized by the magnitude of the demands placed on a client within a session. Under this definition, intensive therapy includes a few specific techniques such as Constraint Induced Aphasia Therapy (CIAT) and Speech Intensive Rehabilitation Intervention (SP-I-R-IT). CIAT places high demands on the patient by restricting use of the strongest areas of the patient’s brain and requiring the weakest areas to work harder. Typical CIAT therapy sessions are intense and last for about 3 hours.[64] One study found that when given intensive CIAT therapy, participant performance in verbal communication in everyday life significantly improved. Each participant in the study also showed improvement on at least one subtest within the Aachen Aphasia Test; which assesses language performance and comprehension in aphasia patients. These results suggest that intensive CIAT therapy is effective in patients with moderate, fluent aphasias in the chronic stage of recovery.[63] SP-I-R-IT focuses heavily on speech production strategies and intervention. SPIRIT therapy has been found to be effective; patients participating in intensive SPIRIT therapy improved performance on standardized measures by 15% after 50 weeks of therapy.[59]

Overall, intensity of aphasia treatment is an area that requires more research. Current research suggests that intense treatment is effective, although the definition of “intense” is variable. Most importantly, intensity of treatment should be determined on a case by case basis and should depend upon recency of stroke and the patient’s stamina, tolerance for therapy, motivation, overall health status, and treatment goals.

Prognosis

There are several outcomes that contribute to a patient's overall outcomes once diagnosed with aphasia including: neuroplasticity, age, overall health status, and patient motivation. Neuroplasticity is the brain's capability of change in response to the environment. Neuroplaticity underlies normal processes such as: typical development, learning & maintaining performance while aging, and the brain's response to a severe injury.[65] Positive outcomes are most prominent when neuroplasticity is maximized for the aphasic patient, and is predicted by the patient's response to the other stated outcomes.[66] The patient's age directly impacts the neuroplasticity the brain can allow, the younger the patient is, the greater plasticity is.[65] Overall health status also greatly impacts outcomes in aphasic patients. If a patient has no underlying health problems, and is young, then they have better outcomes than someone who is older, has severe health issues (such as: obesity, heart disease, cancer, high blood pressure, etc.) in conjunction with aphasia.[66] However, the most important factor affecting the outcomes of a patient with aphasia is a patient's motivation. In order to be successful, regardless of the contributing outcomes, the patient must be highly motivated in order to make the most efficient outcomes. If the patient is not motivated to make positive outcomes in their life after being diagnosed with any type of aphasia, their prognosis to make great improvements is much less than someone who is highly motivated to make positive changes in their life.[65][66] All of these outcomes contribute to success in Wernicke's, Broca's, Global, and Conduction aphasia, and are detailed below:

Wernicke's aphasia

Wernicke’s is considered a more severe form of aphasia, and is more commonly seen in older populations. Wernicke's area is in the left posterior temporal region of the brain, which is an important area for processing language comprehension. Wernicke’s aphasia has shown a high recovery rate and frequent evolution to other forms of aphasia. Though some cases of Wernicke’s aphasia has shown greater improvements than more mild forms of aphasia, people with Wernicke’s aphasia may not reach as high of a level of speech abilities as those with mild forms of aphasia.[67] Wernicke's aphasia is also referred to as receptive or fluent aphasia, due to the ability to speak grammatically and use appropriate prosody. However, much of what the person with aphasia says does not make sense, and often times will produce non-existent words and be unaware what they have said. People with Wernicke's aphasia have difficulties understanding the meaning of spoken words and sentences.[68] Those with Wernicke's aphasia are usually unable to recognize their deficits. They remain completely unaware of even their most profound language deficits. [69]

Broca's aphasia

(Broca’s and Anomic):

The term, Anomic Aphasia, usually refers to patients whose only prevalent symptom is impaired word retrieval in speech and writing.[70] Typically, the spontaneous speech of a person with anomic aphasia is fluent and grammatically correct but contains many word retrieval failures. These failures lead to unusual pauses, talking around the intended word, or substituting the intended word for a different word.[70] Anomic aphasia is the mildest form of aphasia, indicating a likely possibility for better recovery.[71] Patients with Broca’s aphasia may also have difficulty with word retrieval, or anomia. In addition, patients with Broca’s aphasia comprehend spoken and written language better than they can speak or write. These patients self-monitor, are aware of their communicative impairments, and frequently try to repeat or attempt repairs.[70] The preceding factors discussed correlate with a good prognosis for patients with Broca’s aphasia. Many patients with an acute onset of Broca’s aphasia, eventually progress to milder forms of aphasia, such as conduction or anomic.[72]

Therapy for Expressive Aphasia (nonfluent) is beneficial, even for patients with severe nonfluent aphasia. A study conducted by Marangolo and co-workers (2013) administered conversational therapy to patients with severe nonfluent aphasia. The results of the study demonstrated a significant increase in the patient’s expressive language. The authors suggested that an intensive conversational therapy program should be considered for patients with moderately severe nonfluent aphasia in order to enhance the patient's quality of life and improve their language expression.[73] In addition, although Anomic Aphasia is seen to be less severe than other aphasias, therapy is still imperative to help decrease the patient’s word finding deficits. A research study conducted by Harnish and co-workers (2014), provided intense treatment to patients with anomic aphasia. Results of the study concluded significant increases in the participant’s expressive language. These results suggest that an intensive intervention program for patients with anomic aphasia provides a surprisingly quick expressive language increase. Specifically, these patients relearned to correctly produce the problematic words after one to three hours of speech-language therapy.[74]

Global aphasia

Global aphasia is considered a severe impairment in many language aspects since it impacts expressive and receptive language, reading, and writing.[75] Despite these many deficits, there is evidence that has shown individuals benefited from speech language therapy.[76] Even though each case is different, it has been noted that individuals with global aphasia had greater improvements during the second six months following the stroke when compared to the first 6 months.[77] Intense and frequent speech-language therapy had been shown to be more effective, with the addition of daily homework.[76] Improvement has also been shown when the individual was attentive, motivated, and information was presented in multiple ways.[78]

In one study, 23 individuals that had previously received speech-language therapy, but had been dismissed because further recovery was not expected, participated in intense speech-language therapy.[76] Results showed significant improvements in oral and written noun and sentence production, naming actions, and daily communication.[76]

Even though individuals with global aphasia will not become competent speakers, listeners, writers, or readers, goals can be created to improve the individual’s quality of life.[70] Collins (1991) suggests therapy targeting attainable goals that will have the greatest impact on an individual’s daily life, such as getting reliable yes/no answers or providing the patient gestures. Individuals with global aphasia usually respond well to treatment that includes personally relevant information, which is also important to consider for therapy.[70]

Conduction aphasia

Conduction and transcortical aphasias are caused by damage to the white matter tracts. These aphasias spare the cortex of the language centers, but instead create a disconnection between them.

Conduction aphasia is caused by damage to the arcuate fasciculus. The arcuate fasciculus is a white matter tract that connects Broca’s and Wernicke’s areas. Patients with conduction aphasia typically have good language comprehension, but poor speech repetition and mild difficulty with word retrieval and speech production. Patients with conduction aphasia are typically aware of their errors.[70] The awareness of errors and the milder nature of conduction aphasia compared to other types contributes to a positive outcome. Additionally, a case study completed on a 54-year-old man with a large infarct in the arcuate fasciculus indicated that severe conduction aphasia can be successfully treated. Despite his global deficits, he made a full recovery after 30 months.[79]

Transcortical aphasias include transcortical motor aphasia, transcortical sensory aphasia, and mixed transcortical aphasia. Patients with transcortical motor aphasia typically have intact comprehension and awareness of their errors, but poor word finding and speech production. Patients with transcortical sensory and mixed transcortical aphasia have poor comprehension and unawareness of their errors.[70] Despite poor comprehension and more severe deficits in some transcortical aphasias, small studies have indicated that full recovery is possible for all types of transcortical aphasia.[80] Due to the limited research on outcomes for the specific subtypes of these aphasias, it is more important to focus on the other factors and severity of deficits in order to predict a reasonable outcome.

History

The first recorded case of aphasia is from an Egyptian papyrus, the Edwin Smith Papyrus, which details speech problems in a person with a traumatic brain injury to the temporal lobe.[81] During the second half of the 19th century, Aphasia was a major focus for scientists and philosophers who were working in the beginning stages in the field of psychology.[1]

Notable cases

- Ralph Waldo Emerson[82]

- Terry Jones[83]

- Ronald Reagan[84] - Caused by late stages of Alzheimer's Disease.

See also

References

- 1 2 3 Damasio, A.R. (February 1992). "Aphasia.". N Engl J Med. 326 (8): 531–9. doi:10.1056/NEJM199202203260806. PMID 1732792.

- 1 2 3 "American Speech-Language-Hearing Association (ASHA):- Aphasia". asha.org.

- 1 2 Stahl, B; Van Lancker Sidtis, D (2015), "Tapping into neural resources of communication: formulaic language in aphasia therapy", Frontiers in Psychology, 6 (1526): 1–5, doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01526

- ↑ Manasco, M. Hunter (2014). Introduction to Neurogenic Communication Disorders. Jones & Bartlett Learning. p. 72. ISBN 9781449652449.

- 1 2 "What is aphasia? What causes aphasia?". Medical News Today.

- ↑ ἀφασία, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus.

- ↑ ἄφατος, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus.

- ↑ American Speech-Language-Hearing Association (1997-2014)

- ↑ Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (2014). Neurodevelopmental and Neurocognitive Disorders. In Abnormal Psychology (6th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill.

- ↑ Manasco, M. Hunter (2014). Introduction to Neurogenic Communication Disorders. Burlington, MA: Jones & Bartlett Learning. pp. 75–76.

- ↑ Manasco, Hunter (2014). Introduction to Neurogenic Communication Disorders. Jones & Bartlett Learning. p. 71.

- ↑ Alexander, MP; Hillis, AE (2008). Georg Goldenberg; Bruce L Miller; Michael J Aminoff; Francois Boller; D F Swaab, eds. Aphasia. Handbook of Clinical Neurology. 88 (1 ed.). pp. 287–310. doi:10.1016/S0072-9752(07)88014-6. ISBN 9780444518972. OCLC 733092630.

- ↑ Henseler, I.; Regenbrecht, F.; Obrig, H. (12 February 2014). "Lesion correlates of patholinguistic profiles in chronic aphasia: comparisons of syndrome-, modality- and symptom-level assessment". Brain. 137 (3): 918–930. doi:10.1093/brain/awt374. PMID 24525451.

- ↑ "Aphasia". www.asha.org. Retrieved 2015-11-18.

- ↑ Soares-Ishigaki, EC.; Cera, ML.; Pieri, A.; Ortiz, KZ. (2012). "Aphasia and herpes virus encephalitis: a case study". Sao Paulo Med J. 130 (5): 336–41. doi:10.1590/S1516-31802012000500011. PMID 23174874.

- ↑ Naudé, H; Pretorius, E. (3 Jun 2010). "Can herpes simplex virus encephalitis cause aphasia?". Early Child Development and Care. 173 (6): 669–679. doi:10.1080/0300443032000088285. Retrieved 2013-06-08.

- 1 2 3 "Aphasia". MedicineNet.com. Retrieved 2011-05-23.

- ↑ Budd, M.A.; Kortte, K.; Cloutman, L.; et al. (September 2010). "The nature of naming errors in primary progressive aphasia versus acute post-stroke aphasia". Neuropsychology. 24 (5): 581–9. doi:10.1037/a0020287. PMC 3085899

. PMID 20804246.

. PMID 20804246. - ↑ Henseler, I; Regenbrecht, F; Obrig, H (March 2014). "Lesion correlates of patholinguistic profiles in chronic aphasia: comparisons of syndrome-, modality- and symptom-level assessment.". Brain. 137 (Pt 3): 918–30. doi:10.1093/brain/awt374. PMID 24525451.

- ↑ Kuljic-Obradovic, DC (July 2003). "Subcortical aphasia: three different language disorder syndromes?". European Journal of Neurology. 10 (4): 445–8. doi:10.1046/j.1468-1331.2003.00604.x. PMID 12823499.

- ↑ Kreisler, A; Godefroy, O; Delmaire, C; Debachy, B; Leclercq, M; Pruvo, JP; Leys, D (14 March 2000). "The anatomy of aphasia revisited.". Neurology. 54 (5): 1117–23. doi:10.1212/wnl.54.5.1117. PMID 10720284.

- ↑ Coppens, P; Hungerford, S; Yamaguchi, S; Yamadori, A (December 2002). "Crossed aphasia: an analysis of the symptoms, their frequency, and a comparison with left-hemisphere aphasia symptomatology.". Brain and Language. 83 (3): 425–63. doi:10.1016/s0093-934x(02)00510-2. PMID 12468397.

- ↑ Mariën, P; Paghera, B; De Deyn, PP; Vignolo, LA (February 2004). "Adult crossed aphasia in dextrals revisited.". Cortex. 40 (1): 41–74. doi:10.1016/s0010-9452(08)70920-1. PMID 15070002.

- ↑ "Primary Progressive Aphasia". www.asha.org. Retrieved 2015-11-15.

- ↑ Quigg M, Fountain NB (March 1999). "Conduction aphasia elicited by stimulation of the left posterior superior temporal gyrus". J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatr. 66 (3): 393–6. doi:10.1136/jnnp.66.3.393. PMC 1736266

. PMID 10084542.

. PMID 10084542. - ↑ "Fentanyl Transdermal Official FDA information, side effects and uses". Drug Information Online.

- ↑ "FENTANYL TRANSDERMAL SYSTEM patch, extended release". DailyMed. Retrieved 2013-06-08.

- ↑ Kolb, Bryan; Whishaw, Ian Q. (2003). Fundamentals of human neuropsychology. [New York]: Worth. pp. 502, 505, 511. ISBN 0-7167-5300-6. OCLC 464808209.

- ↑ Manasco, M. Hunter. Introduction to Neurogenic Communication Disorders. Jones and Bartlett Learning. p. 7.

- 1 2 Goodglass, H., Kaplan, E., & Barresi, B. (2001). The assessment of aphasia and related disorders. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

- ↑ Kertesz, A. (2006). Western Aphasia Battery-Revised (WAB-R). Austin, TX: Pro-Ed.

- 1 2 "Common Classifications of Aphasia". www.asha.org. Retrieved 2015-11-19.

- ↑ Kolb, Bryan; Whishaw, Ian Q. (2003). Fundamentals of human neuropsychology. [New York]: Worth. pp. 502–504. ISBN 0-7167-5300-6. OCLC 464808209.

- ↑ Godefroy O.; Dubois C.; Debachy B.; Leclerc M.; Kreisler A. (2002). "Vascular aphasias: main characteristics of patients hospitalized in acute stroke units". Stroke. 33: 702–705. doi:10.1161/hs0302.103653.

- ↑ Ross K.B.; Wertz R.T. (2001). "Type and severity of aphasia during the first seven months poststroke". Journal of Medical Speech-Language Pathology. 9: 31–53.

- ↑ Coltheart, Max; Kay, Janice; Lesser, Ruth (1992). PALPA psycholinguistic assessments of language processing in aphasia. Hillsdale, N.J: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. ISBN 0-86377-166-1.

- ↑ Porter, G., & Howard, D. (2004). CAT: comprehensive aphasia test. Psychology Press.

- ↑ Mesulam MM (April 2001). "Primary progressive aphasia". Ann. Neurol. 49 (4): 425–32. doi:10.1002/ana.91. PMID 11310619.

- ↑ Wilson SM, Henry ML, Besbris M, et al. (July 2010). "Connected speech production in three variants of primary progressive aphasia". Brain. 133 (Pt 7): 2069–88. doi:10.1093/brain/awq129. PMC 2892940

. PMID 20542982.

. PMID 20542982. - 1 2 Harciarek M, Kertesz A (September 2011). "Primary progressive aphasias and their contribution to the contemporary knowledge about the brain-language relationship". Neuropsychol Rev. 21 (3): 271–87. doi:10.1007/s11065-011-9175-9. PMC 3158975

. PMID 21809067.

. PMID 21809067. - ↑ Gorno-Tempini ML, Hillis AE, Weintraub S, et al. (March 2011). "Classification of primary progressive aphasia and its variants". Neurology. 76 (11): 1006–14. doi:10.1212/WNL.0b013e31821103e6. PMC 3059138

. PMID 21325651.

. PMID 21325651. - ↑ Carlson, Neil (2013). Physiology of Behavior. New York: Pearson. pp. 494–496.

- ↑ Manasco, M. Hunter (2014). Introduction to Neurogenic Communication Disorders. Burlington, MA: Jones and Bartlett Learning. ISBN 978-1-4496-5244-9.

- 1 2 3 4 Schmitz, Thomas J.; O'Sullivan, Susan B. (2007). Physical rehabilitation. Philadelphia: F.A. Davis. ISBN 0-8036-1247-8. OCLC 70119705.

- ↑ "Aphasia". asha.org.

- ↑ Manasco, M. Hunter. Introduction to Neurogenic Communication Disorders. Jones & Bartlett Learning. p. 97. ISBN 9781449652449.

- ↑ Beeson, P. M., Egnor, H. (2007), Combining treatment for written and spoken naming, Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society, 12(6); 816-827.

- ↑ "Aphasia". American Speech Language Hearing Association. Retrieved from http://www.asha.org/PRPSpecificTopic.aspx?folderid=8589934663§ion=Treatment

- ↑ Alexander, MP; Hillis, AE (2008). "Aphasia". In Georg Goldenberg; Bruce L Miller; Michael J Aminoff; Francois Boller; D F Swaab. Neuropsychology and Behavioral Neurology: Handbook of Clinical Neurology. 88. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 287–310. ISBN 978-0-444-51897-2. OCLC 733092630.

- ↑ Manasco, Hunter. "The Aphasias". Introduction to Neurogenic Communication Disorders. p. 93.

- ↑ Davis & Stanton, 2005. Semantic Feature Analysis as a Functional Therapy Tool. Contemporary Issues In Communication Science and Disorders." 35, 85-92.

- ↑ Maddy, K.M.; Capilouto, G.J.; McComas, K.L. "The effectiveness of semantic feature analysis: An evidence-based systematic review". Annals of Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine. 57 (4): 254–267. doi:10.1016/j.rehab.2014.03.002.

- ↑ Norton A, Zipse L, Marchina S, Schlaug G (July 2009). "Melodic Intonation Therapy: shared insights on how it is done and why it might help". Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1169: 431–6. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.04859.x. PMC 2780359

. PMID 19673819.

. PMID 19673819. - ↑ van der Meulen, I; van de Sandt-Koenderman, ME; Ribbers, GM (January 2012). "Melodic Intonation Therapy: present controversies and future opportunities". Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 93 (1 Suppl): S46–52. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2011.05.029. PMID 22202191.

- ↑ "Melodic-Intonation-Therapy and Speech-Repetition-Therapy for Patients With Non-fluent Aphasia". clinicaltrials.gov.

- ↑ Stahl, B; Kotz, SA (2013). "Facing the music: Three issues in current research on singing and aphasia". Frontiers in Psychology. 5 (1033): 1–4. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2014.01033. ISSN 1664-1078.

- 1 2 van de Sandt-Koenderman WM (February 2011). "Aphasia rehabilitation and the role of computer technology: can we keep up with modern times?". Int J Speech Lang Pathol. 13 (1): 21–7. doi:10.3109/17549507.2010.502973. PMID 21329407.

- ↑ Bhogal SK; Teasell R; Speechley M (2003). "Intensity of aphasia therapy, impact on recovery". Stroke. 34 (4): 987–993. doi:10.1161/01.str.0000062343.64383.d0.

- 1 2 3 4 Martins IP; Leal G; Fonseca I; Farrajota L; Aguiar M; Fonseca J; Ferro JM (2013). "A randomized, rater-blinded, parallel trial of intensive speech therapy in sub-acute post-stroke aphasia: the SP-I-R-IT study". International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders. 48 (4): 421–431. doi:10.1111/1460-6984.12018.

- 1 2 3 4 Cherney LR; Patterson JP; Raymer AM (2011). "Intensity of aphasia therapy: Evidence and efficacy". Current Neurology and Neuroscience Reports. 11 (6): 560–569. doi:10.1007/s11910-011-0227-6.

- 1 2 3 Sage K; Snell C; Lambon Ralph MA (2011). "How intensive does anomia therapy for people with aphasia need to be?". Neuropsychological Rehabilitation. 21 (1): 26–41. doi:10.1080/09602011.2010.528966.

- 1 2 Palmer R (2015). "Innovations in aphasia treatment after stroke: Technology to the rescue". British Journal of Neuroscience Nursing. 38: 38–42. doi:10.12968/bjnn.2015.11.sup2.38.

- 1 2 3 Wilssens I; Vandenborre D; Dun K; Verhoeven J; Visch-Brink E; Mariën P (2015). "Constraint-induced aphasia therapy versus intensive semantic treatment in fluent aphasia". American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology. 24: 281–294. doi:10.1044/2015_ajslp-14-0018.

- ↑ Johnson ML; Taub E; Harper LH; Wade JT; Bowman MH; Bishop-McKay S; Uswatte G (2014). "An enhanced protocol for constraint-induced aphasia therapy II: A case series". American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology. 23 (1): 60–72. doi:10.1044/1058-0360(2013/12-0168).

- 1 2 3 Bayles K; Tomodea CK. "Neuroplasticity: Implications for treating cognitive-communication disorders". ASHA Convention 2010.

- 1 2 3 Raymer AM (2008). "Translational research in aphasia: From neuroscience to neurorehabilitation". Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 51: 259–275. doi:10.1044/1092-4388(2008/020).

- ↑ Laska AC; Hellblom A; Murray V; Kahan T; Arbin M (2001). "Aphasia in acute stroke and relation to outcome". Journal of Internal Medicine. 249: 413–422. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2796.2001.00812.x.

- ↑ "Wernicke's Aphasia". The National Aphasia Association. Retrieved 26 November 2016.

- ↑ Manasco, M. H. (2014). Introduction to Neurogenic Communication Disorders. Burlington, MA: Jones & Bartlett Learning.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Brookshire R. "Introduction to neurogenic communication disorders (7th edition). St. Louis, MO: Mosby".

- ↑ Squire LR; Dronkers NF; Baldo JV (2009). "Encyclopedia of neuroscience".

- ↑ Aminoff, M. J., Daroff, R. B., Foundas, A. L., Knaus, T. A., & Shields, J. (2014). Encyclopedia of the neurological sciences. Retrieved from http://topics.sciencedirect.com/

- ↑ Marangolo P.; Fiori V.; Caltagirone C.; Marini A. (2013). "How Conversational Therapy influences language recovery in chronic non-fluent aphasia". Neuropsychological Rehabilitation. 23 (5): 715–731. doi:10.1080/09602011.2013.804847.

- ↑ Harnish S. M.; Morgan J.; Lundine J. P.; Bauer A.; Singletary F.; Benjamin M. L.; Crosson B. (2014). "Dosing of a Cued Picture-Naming Treatment for Anomia". American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology. 23 (2): S285–S299. doi:10.1044/2014_AJSLP-13-0081.

- ↑ Demeurisse G.; Capon A. (1987). "Language recovery in aphasic stroke patients: Clinical, CT and CBF studies". Aphasiology. 1 (4): 301–315. doi:10.1080/02687038708248851.

- 1 2 3 4 Basso A; Macis M (2001). "Therapy efficacy in chronic aphasia". Behavioural Neurology. 24 (4): 317–325. doi:10.1155/2011/313480.

- ↑ Sarno M.; Levita E. (1971). "Natural course of recovery in severe aphasia". Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 52: 175–178.

- ↑ Kendall, D. L., Oelke, M., Brookshire, C. E., & Nadeau, S. E. (2015). The influence of phonomotor treatment on word retrieval abilities in 26 individuals with chronic aphasia: An open trial. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 1-15.

- ↑ Kwon H.G.; Jang S.H. (2011). "Excellent recovery of aphasia in a patient with complete injury of the arcuate fasciculus in the dominant hemisphere". NeuroRehabilitation. 29: 401–404. doi:10.3233/NRE-2011-0718.

- ↑ Flamand-Roze C.; Cauquil-Michon C.; Roze E.; Souillard-Scemama R.; Maintigneux L.; Ducreux D.; Adams D.; Denier C. (2011). "Aphasia in border-zone infarcts has a specific initial pattern and good long-term prognosis". European Journal of Neurology. 18: 1397–1401. doi:10.1111/j.1468-1331.2011.03422.x.

- ↑ McCrory PR, Berkovic SF (December 2001). "Concussion: the history of clinical and pathophysiological concepts and misconceptions". Neurology. 57 (12): 2283–9. doi:10.1212/WNL.57.12.2283. PMID 11756611.

- ↑ Richardson, Robert G. (1995). Emerson: the mind on fire: a biography. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-08808-5. OCLC 31206668.

- ↑ http://www.cnn.com/2016/09/23/health/terry-jones-monty-python-aphasia/

- ↑ http://www.cbsnews.com/news/ronald-reagan-turns-89/

External links

| Library resources about Aphasia |

| Look up aphasia or aphemia in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Aphasia at DMOZ

- Luria's Areas of the Human Cortex Involved in Language Illustrated summary of Luria's book Traumatic Aphasia

- Video clips showing patients with Expressive-type aphasia

- A video clip with a patient exhibiting Receptive aphasia

- American Speech-Language-Hearing Association Glossary: Primary Progressive Aphasia (PPA)