Antisemitism in the Russian Empire

| Part of a series on |

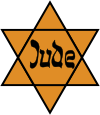

| Antisemitism |

|---|

Part of Jewish history |

|

Antisemitism on the Web |

|

Opposition |

|

|

Antisemitism in the Russian Empire was essentially the same as already formed in the West.

Involvement of the Orthodox Church

Yuri Tabak describes the history of antisemitism in Russia as having the same forms "already traditional in the West".[1] Tabak describes Christian-Jewish relations in Russia as having "maintained a more or less neutral attitude" during periods of calm but with a "mixture of fear and hatred of Jews characteristic of medieval Christian consciousness" smouldering below the surface. He asserts that social, economic, religious or political changes could bring this undercurrent of antisemitism to the surface, changing the Christian populace into "a fanatical crowd capable of murder and pillage."[2]

Tabak asserts, however, that "the fundamental difference in the conduct of anti-Jewish measures in Russia (compared to Western Europe), ... lies in the much lesser role played by the Russian Orthodox Church in the conduct of this policy," According to Tabak, it is much harder to find examples of involvement of high-ranking Russian Orthodox leaders in antisemitic policies. He asserts that "(a)ll anti-Jewish decisions were conducted by state administrative organs, acting on the authority of emperors, state committees and ministries." He explains that "(e)ven if the Ecclesiastical Collegium under Peter the Great and, later, the Holy Synod, agreed with and approved certain measures, it is important to remember that these aforementioned institutions were essentially government departments." Thus, he concludes that "(a)lthough it would be entirely natural to suppose that the Church authorities had a particular influence on the State in the conduct of anti-Jewish measures and even that these were indeed initiated by the Church, there is no conclusive evidence to support this"[1]

Tabak concedes that the Russian church can be criticized for "its inability to express an independent opinion and for its failure to demonstrate love for one's neighbour and defence of the persecuted in accordance with the basic teachings of the Gospel". He asserts that "unlike the Western church, the Russian Orthodox Church took no steps to protect the Jews." Moreover, he asserts that despite the lack of an official church position on the Jewish question, many clerics and priests of the Russian Orthodox Church were prone to antisemitic attitudes. The first Kishinev pogrom of 1903 was led by Eastern Orthodox priests.[3]

However, Tabak also notes that "an equal number of Russian Orthodox clerics, including senior hierarchs, openly defended persecuted Jews, at least from the second half of the nineteenth century." He asserts that "(i)n Russia, perhaps more than in the West, hierarchs of the church and professors in the theological academies refuted the accusations that Jews conducted pogroms and ritual sacrifices and were organising a 'worldwide conspiracy', as they fought for the social rights of Jews" although he concedes that these declarations did little to moderate "the general hatred of Jews characteristic of the Russian population since medieval times".[1]

Tabak asserts that, in contrast to the gradual expansion of religious and social rights for Western European Jews, "no such movement took place in Russia." He attributes this difference to the "weakness of any liberal and democratic tendencies" in the course of Russian history and notes that "the Renaissance, the Enlightenment and the Reformation... bypassed Russia."[1]

History

18th century

Russia remained unaffected by the liberalising tendencies of this era with respect to the status of Jews. Before the 18th century Russia maintained an exclusionary policy towards Jews, in accordance with the anti-Jewish precepts of the Russian Orthodox Church.[4] When asked about admitting Jews into the Empire, Peter the Great stated "I prefer to see in our midst nations professing Mohammedanism and paganism rather than Jews. They are rogues and cheats. It is my endeavor to eradicate evil, not to multiply it."[5] More active discriminatory policies began when the partition of Poland in the 18th century which resulted, for the first time in Russian history, in the possession of land with a large population of Jews.[6] This land was designated as the Pale of Settlement from which Jews were forbidden to migrate into the interior of Russia.[6] In 1772, Catherine II forced the Jews of the Pale of Settlement to stay in their shtetls and forbade them from returning to the towns that they occupied before the partition of Poland.[7]

19th century

A series of genocidal persecutions, or pogroms, against Jews took place in Russia. These arose from a variety of motivations, not all of them related to Christian antisemitism. They have been attributed in part to religiously motivated antisemitism arising from the canard that Jews were responsible for the crucifixion of Jesus.[8][9] The primary trigger of the pogroms, however, is considered to have been the assassination of Tsar Alexander II.[10]

Pogroms

The first pogrom is often considered to be the 1821 anti-Jewish riots in Odessa (modern Ukraine) after the death of the Greek Orthodox patriarch in Constantinople, in which 14 Jews were killed.[11] The virtual Jewish encyclopedia claims that initiators of 1821 pogroms were the local Greeks that used to have a substantial diaspora in the port cities of what was known as Novorossiya.[12]

Long-standing repressive policies and attitudes towards the Jews were intensified after the assassination of Tsar Alexander II on 13 March 1881. This event was blamed on the Jews and sparked widespread Anti-Jewish pogroms in the Russian Empire, which lasted for three years, from 27 April 1881 to 1884.[13] A hardening of official attitudes under Tsar Alexander III and his ministers, resulted in the May Laws of 1882 which severely restricted the civil rights of Jews within the Russian Empire. The Tsar's minister Konstantin Petrovich Pobedonostsev stated the aim of the government with regard to the Jews was that "One third will die out, one third will leave the country and one third will be completely dissolved in the surrounding population".[13] In the event, the pogroms and the repressive legislation did indeed result in the mass emigration of Jews to western Europe and America. Between 1881 and the outbreak of the First World War, an estimated 2.5 million Jews left Russia - one of the largest group migrations in recorded history.[14]

See also

- History of the Jews in the Soviet Union

- History of the Jews in Russia

- Antisemitism in the Russian Federation

- Antisemitism in the Soviet Union

- Racism in Russia

References

- 1 2 3 4 Tabak, Yuri. "Relations between the Russian Orthodox Church and Judaism: Past and Present".

- ↑ Tabak, Yuri. "Relations between the Russian Orthodox Church and Judaism: Past and Present".

The Christian community, linked by numerous trading and economic ties to the Jewish community, maintained a more or less neutral attitude towards the Jews during these periods of calm, and, on the personal level, even conducted individual friendships. However, the mixture of fear and hatred of Jews characteristic of medieval Christian consciousness (the religious roots of which will be discussed below) never completely disappeared: these latent emotions smouldered beneath the socio-economic necessity of maintaining the status quo. It only took the emergence of any new circumstances in society, whether in the social, economic, religious, or governmental spheres, or in the internal dynamics of the Jewish-Christian debate, for these latent emotions to reach boiling point. The defenceless Jewish community would then become the target of harsh economic measures, a pawn in someone's political games, or a convenient focus for the lower classes to vent their own discontent. These factors readily combined to ignite the smouldering embers of religious hatred: the uneducated Christian masses could change overnight into a fanatical crowd capable of murder and pillage.

- ↑ "Jewish Massacre Denounced", New York Times, April 28, 1903, p 6.

- ↑ Steven Beller (2007) Antisemitism: A Very Short Introduction: 14

- ↑ Levitats, Isaac (1943). The Jewish Community in Russia, 1772-1844. New York: Columbia University Press. pp. 20–21.

- 1 2 Steven Beller (2007) Antisemitism: A Very Short Introduction: 28

- ↑ Weiner, Rebecca. "The Virtual Jewish History Tour".

- ↑ Volf, Miroslav (2008). "Christianity and Violence". In Hess, Richard S.; Martens, E.A. War in the Bible and terrorism in the twenty-first century. Eisenbrauns. p. 13. ISBN 978-1-57506-803-9. Retrieved June 1, 2010.

- ↑ Lambroza, Shlomo (1992). Klier, John D.; Lambroza, Shlomo, eds. Pogroms: Anti-Jewish Violence in Modern Russian History. Cambridge University Press. p. 205. ISBN 0-521-40532-7.

- ↑ Jewish Chronicle, May 6, 1881, cited in Benjamin Blech, Eyewitness to Jewish History

- ↑ Odessa pogroms at the Center of Jewish Self-Education "Moria".

- ↑ Pogrom (Virtual Jewish Encyclopedia) (Russian)

- 1 2 Richard Rubenstein and John Roth (1887) Approaches to Auschwitz. London, SCM Press: 96

- ↑ Ronnie S. Landau (1992) The Nazi Holocaust. IB Tauris, London and New York: 57