Vasopressin

| View/Edit Human | View/Edit Mouse |

Vasopressin, also known as antidiuretic hormone (ADH), is a neurohypophysial hormone found in most mammals. In most species it contains arginine and is thus also called arginine vasopressin (AVP) or argipressin.[4] Its two primary functions are to retain water in the body and to constrict blood vessels.[5] Vasopressin regulates the body's retention of water by acting to increase water reabsorption in the kidney's collecting ducts, the tubules which receive the very dilute urine produced by the functional unit of the kidney, the nephrons.[6][7]

Vasopressin is a peptide hormone that increases water permeability of the kidney's collecting duct and distal convoluted tubule by inducing translocation of aquaporin-CD water channels in the plasma membrane of collecting duct cells.[8] It also increases peripheral vascular resistance, which in turn increases arterial blood pressure. It plays a key role in homeostasis, by the regulation of water, glucose, and salts in the blood. It is derived from a preprohormone precursor that is synthesized in the hypothalamus and stored in vesicles at the posterior pituitary.

Most of vasopressin is stored in the posterior pituitary to be released into the bloodstream. However, some AVP may also be released directly into the brain, and accumulating evidence suggests it plays an important role in social behavior, sexual motivation and pair bonding, and maternal responses to stress.[9] It has a very short half-life between 16–24 minutes.[7]

Physiology

Function

One of the most important roles of AVP is to regulate the body's retention of water; it is released when the body is dehydrated and causes the kidneys to conserve water, thus concentrating the urine and reducing urine volume. At high concentrations, it also raises blood pressure by inducing moderate vasoconstriction. In addition, it has a variety of neurological effects on the brain, having been found, for example, to influence pair-bonding in voles. The high-density distributions of vasopressin receptor AVPr1a in prairie vole ventral forebrain regions have been shown to facilitate and coordinate reward circuits during partner preference formation, critical for pair bond formation.[10]

A very similar substance, lysine vasopressin (LVP) or lypressin, has the same function in pigs and is often used in human therapy.[11]

Kidney

Vasopressin has three main effects by which it contributes to increased urine osmolarity (increased concentration) and decreased water excretion:

- Increasing the water permeability of distal convoluted tubule and collecting duct cells in the kidney, thus allowing water reabsorption and excretion of more concentrated urine, i.e., antidiuresis. This occurs through increased transcription and insertion of water channels (Aquaporin-2) into the apical membrane of distal convoluted tubule and collecting duct epithelial cells. Aquaporins allow water to move down their osmotic gradient and out of the nephron, increasing the amount of water re-absorbed from the filtrate (forming urine) back into the bloodstream. This effect is mediated by V2 receptors. Vasopressin also increases the concentration of calcium in the collecting duct cells, by episodic release from intracellular stores. Vasopressin, acting through cAMP, also increases transcription of the aquaporin-2 gene, thus increasing the total number of aquaporin-2 molecules in collecting duct cells.

- Increasing permeability of the inner medullary portion of the collecting duct to urea by regulating the cell surface expression of urea transporters,[12] which facilitates its reabsorption into the medullary interstitium as it travels down the concentration gradient created by removing water from the connecting tubule, cortical collecting duct, and outer medullary collecting duct.

- Acute increase of sodium absorption across the ascending loop of henle. This adds to the countercurrent multiplication which aids in proper water reabsorption later in the distal tubule and collecting duct.[13]

Serum osmolarity/osmolality is also affected by vasopressin due to its role in keeping proper electrolytic balance in the blood stream. Improper balance can lead to dehydration, alkalosis, acidosis or other life-threatening changes. The hormone ADH is partly responsible for this process by controlling the amount of water the body retains from the kidney when filtering the blood stream.[14]

Cardiovascular system

Vasopressin increases peripheral vascular resistance (vasoconstriction) and thus increases arterial blood pressure. This effect appears small in healthy individuals; however it becomes an important compensatory mechanism for restoring blood pressure in hypovolemic shock such as that which occurs during hemorrhage.

Central nervous system

Vasopressin released within the brain has many actions:

- Vasopressin is released into the brain in a circadian rhythm by neurons of the suprachiasmatic nucleus.[16]

- Vasopressin released from centrally projecting hypothalamic neurons is involved in aggression, blood pressure regulation, and temperature regulation.

- It is likely that vasopressin acts in conjunction with corticotropin-releasing hormone to modulate the release of corticosteroids from the adrenal gland in response to stress, particularly during pregnancy and lactation in mammals.[17][18][19]

- Selective AVPr1a blockade in the ventral pallidum has been shown to prevent partner preference in prairie voles, suggesting that these receptors in this ventral forebrain region are crucial for pair bonding.[10]

- Recent evidence suggests that vasopressin may have analgesic effects. The analgesia effects of vasopressin were found to be dependent on both stress and sex.[20]

Evidence for this comes from experimental studies in several species, which indicate that the precise distribution of vasopressin and vasopressin receptors in the brain is associated with species-typical patterns of social behavior. In particular, there are consistent differences between monogamous species and promiscuous species in the distribution of AVP receptors, and sometimes in the distribution of vasopressin-containing axons, even when closely related species are compared.[21] Moreover, studies involving either injecting AVP agonists into the brain or blocking the actions of AVP support the hypothesis that vasopressin is involved in aggression toward other males. There is also evidence that differences in the AVP receptor gene between individual members of a species might be predictive of differences in social behavior.

One study has suggested that genetic variation in male humans affects pair-bonding behavior. The brain of males uses vasopressin as a reward for forming lasting bonds with a mate, and men with one or two of the genetic alleles are more likely to experience marital discord. The partners of the men with two of the alleles affecting vasopressin reception state disappointing levels of satisfaction, affection, and cohesion.[22]

Vasopressin receptors distributed along the reward circuit pathway, to be specific in the ventral pallidum, are activated when AVP is released during social interactions such as mating, in monogamous prairie voles. The activation of the reward circuitry reinforces this behavior, leading to conditioned partner preference, and thereby initiates the formation of a pair bond.[23]

Regulation

Vasopressin is secreted from the posterior pituitary gland in response to reductions in plasma volume, in response to increases in the plasma osmolality, and in response to cholecystokinin (CCK) secreted by the small intestine:

- Secretion in response to reduced plasma volume is activated by pressure receptors (baroreceptors) in the veins, atria, and carotid sinuses.

- Secretion in response to increases in plasma osmotic pressure is mediated by osmoreceptors in the hypothalamus.

- Secretion in response to increases in plasma CCK is mediated by an unknown pathway.

The neurons that make AVP, in the hypothalamic supraoptic nuclei (SON) and paraventricular nuclei (PVN), are themselves osmoreceptors, but they also receive synaptic input from other osmoreceptors located in regions adjacent to the anterior wall of the third ventricle. These regions include the organum vasculosum of the lamina terminalis and the subfornical organ.

Many factors influence the secretion of vasopressin:

- Ethanol (alcohol) reduces the calcium-dependent secretion of AVP by blocking voltage-gated calcium channels in neurohypophyseal nerve terminals in rats.[24]

- Angiotensin II stimulates AVP secretion, in keeping with its general pressor and pro-volumic effects on the body.[25]

- Atrial natriuretic peptide inhibits AVP secretion, in part by inhibiting Angiotensin II-induced stimulation of AVP secretion.[25]

Secretion

The main stimulus for secretion of vasopressin is increased osmolality of plasma. Reduced volume of extracellular fluid also has this effect, but is a less sensitive mechanism.

The AVP that is measured in peripheral blood is almost all derived from secretion from the posterior pituitary gland (except in cases of AVP-secreting tumours). Vasopressin is produced by magnocellular neurosecretory neurons in the Paraventricular nucleus of hypothalamus (PVN) and Supraoptic nucleus (SON). It then travels down the axon through the infundibulum within neurosecretory granules that are found within Herring bodies, localized swellings of the axons and nerve terminals. These carry the peptide directly to the posterior pituitary gland, where it is stored until released into the blood. However, there are two other sources of AVP with important local effects:

- AVP is also synthesized by magnocellular neurosecretory neurons at the PVN, transported and released at the median eminence, which then travels through the hypophyseal portal system to the anterior pituitary where it stimulates corticotropic cells synergistically with CRH to produce ACTH (by itself it is a weak secretagogue).[26]

- Vasopressin is also released into the brain by several different populations of smaller patterns.

Receptors

Below is a table summarizing some of the actions of AVP at its four receptors, differently expressed in different tissues and exerting different actions:

| Type | Second messenger system | Locations | Actions | Agonists | Antagonists |

| AVPR1A | Phosphatidylinositol/calcium | Liver, kidney, peripheral vasculature, brain | Vasoconstriction, gluconeogenesis, platelet aggregation, and release of factor VIII and von Willebrand factor; social recognition,[27] circadian tau[28] | Felypressin | |

| AVPR1B or AVPR3 | Phosphatidylinositol/calcium | Pituitary gland, brain | Adrenocorticotropic hormone secretion in response to stress;[29] social interpretation of olfactory cues[30] | ||

| AVPR2 | Adenylate cyclase/cAMP | Basolateral membrane of the cells lining the collecting ducts of the kidneys (especially the cortical and outer medullary collecting ducts) | Insertion of aquaporin-2 (AQP2) channels (water channels). This allows water to be reabsorbed down an osmotic gradient, and so the urine is more concentrated. Release of von Willebrand factor and surface expression of P-selectin through exocytosis of Weibel-Palade bodies from endothelial cells[31][32] | AVP, desmopressin | "-vaptan" diuretics, i.e. tolvaptan |

Structure and relation to oxytocin

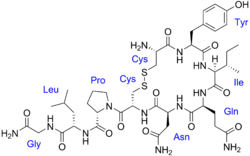

The vasopressins are peptides consisting of nine amino acids (nonapeptides). (NB: the value in the table above of 164 amino acids is that obtained before the hormone is activated by cleavage.) The amino acid sequence of arginine vasopressin (argipressin) is Cys-Tyr-Phe-Gln-Asn-Cys-Pro-Arg-Gly-NH2, with the cysteine residues forming a disulfide bond and the C-terminus of the sequence converted to a primary amide.[33] Lysine vasopressin (lypressin) has a lysine in place of the arginine as the eighth amino acid, and is found in pigs and some related animals, whereas arginine vasopressin is found in humans.[34]

The structure of oxytocin is very similar to that of the vasopressins: It is also a nonapeptide with a disulfide bridge and its amino acid sequence differs at only two positions (see table below). The two genes are located on the same chromosome separated by a relatively small distance of less than 15,000 bases in most species. The magnocellular neurons that secrete vasopressin are adjacent to magnocellular neurons that secrete oxytocin, and are similar in many respects. The similarity of the two peptides can cause some cross-reactions: oxytocin has a slight antidiuretic function, and high levels of AVP can cause uterine contractions.[35][36]

Below is a table showing the superfamily of vasopressin and oxytocin neuropeptides:

| Vertebrate Vasopressin Family | ||

|---|---|---|

| Cys-Tyr-Phe-Gln-Asn-Cys-Pro-Arg-Gly-NH2 | Argipressin (AVP, ADH) | Most mammals |

| Cys-Tyr-Phe-Gln-Asn-Cys-Pro-Lys-Gly-NH2 | Lypressin (LVP) | Pigs, hippos, warthogs, some marsupials |

| Cys-Phe-Phe-Gln-Asn-Cys-Pro-Arg-Gly-NH2 | Phenypressin | Some marsupials |

| Cys-Tyr-Ile-Gln-Asn-Cys-Pro-Arg-Gly-NH2 | Vasotocin† | Non-mammals |

| Vertebrate Oxytocin Family | ||

| Cys-Tyr-Ile-Gln-Asn-Cys-Pro-Leu-Gly-NH2 | Oxytocin (OXT) | Most mammals, ratfish |

| Cys-Tyr-Ile-Gln-Asn-Cys-Pro-Pro-Gly-NH2 | Prol-Oxytocin | Some New World monkeys, northern tree shrews |

| Cys-Tyr-Ile-Gln-Asn-Cys-Pro-Ile-Gly-NH2 | Mesotocin | Most marsupials, all birds, reptiles, amphibians, lungfishes, coelacanths |

| Cys-Tyr-Ile-Gln-Ser-Cys-Pro-Ile-Gly-NH2 | Seritocin | Frogs |

| Cys-Tyr-Ile-Ser-Asn-Cys-Pro-Ile-Gly-NH2 | Isotocin | Bony fishes |

| Cys-Tyr-Ile-Ser-Asn-Cys-Pro-Gln-Gly-NH2 | Glumitocin | skates |

| Cys-Tyr-Ile-Asn/Gln-Asn-Cys-Pro-Leu/Val-Gly-NH2 | Various tocins | Sharks |

| Invertebrate VP/OT Superfamily | ||

| Cys-Leu-Ile-Thr-Asn-Cys-Pro-Arg-Gly-NH2 | Diuretic Hormone | Locust |

| Cys-Phe-Val-Arg-Asn-Cys-Pro-Thr-Gly-NH2 | Annetocin | Earthworm |

| Cys-Phe-Ile-Arg-Asn-Cys-Pro-Lys-Gly-NH2 | Lys-Connopressin | Geography & imperial cone snail, pond snail, sea hare, leech |

| Cys-Ile-Ile-Arg-Asn-Cys-Pro-Arg-Gly-NH2 | Arg-Connopressin | Striped cone snail |

| Cys-Tyr-Phe-Arg-Asn-Cys-Pro-Ile-Gly-NH2 | Cephalotocin | Octopus |

| Cys-Phe-Trp-Thr-Ser-Cys-Pro-Ile-Gly-NH2 | Octopressin | Octopus |

| †Vasotocin is the evolutionary progenitor of all the vertebrate neurohypophysial hormones.[37] | ||

Role in disease

Lack of AVP

Decreased AVP release (neurogenic - i.e. due to alcohol intoxication or tumour) or decreased renal sensitivity to AVP (nephrogenic, i.e. by mutation of V2 receptor or AQP) leads to diabetes insipidus, a condition featuring hypernatremia (increased blood sodium concentration), polyuria (excess urine production), and polydipsia (thirst).

Excess AVP

High levels of AVP secretion may lead to hyponatremia. In many cases, the AVP secretion is appropriate (due to severe hypovolemia), and the state is labelled "hypovolemic hyponatremia". In certain disease states (heart failure, nephrotic syndrome) the body fluid volume is increased but AVP production is not suppressed for various reasons; this state is labelled "hypervolemic hyponatremia". A proportion of cases of hyponatremia feature neither hyper- nor hypovolemia. In this group (labelled "euvolemic hyponatremia"), AVP secretion is either driven by a lack of cortisol or thyroxine (hypoadrenalism and hypothyroidism, respectively) or a very low level of urinary solute excretion (potomania, low-protein diet), or it is entirely inappropriate. This last category is classified as the syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone (SIADH).[38]

SIADH in turn can be caused by a number of problems. Some forms of cancer can cause SIADH, particularly small cell lung carcinoma but also a number of other tumors. A variety of diseases affecting the brain or the lung (infections, bleeding) can be the driver behind SIADH. A number of drugs has been associated with SIADH, such as certain antidepressants (serotonin reuptake inhibitors and tricyclic antidepressants), the anticonvulsant carbamazepine, oxytocin (used to induce and stimulate labor), and the chemotherapy drug vincristine. It has also been associated with fluoroquinolones (including ciprofloxacin and moxifloxacin).[7] Finally, it can occur without a clear explanation.[38]

Hyponatremia can be treated pharmaceutically through the use of vasopressin receptor antagonists.[38]

Pharmacology

Vasopressin analogues

Vasopressin agonists are used therapeutically in various conditions, and its long-acting synthetic analogue desmopressin is used in conditions featuring low vasopressin secretion, as well as for control of bleeding (in some forms of von Willebrand disease and in mild haemophilia A) and in extreme cases of bedwetting by children. Terlipressin and related analogues are used as vasoconstrictors in certain conditions. Use of vasopressin analogues for esophageal varices commenced in 1970.[39]

Vasopressin infusions are also used as second line therapy in septic shock patients not responding to fluid resuscitation or infusions of catecholamines (e.g., dopamine or norepinephrine).

The role of vasopressin analogues in cardiac arrest

Injection of vasopressors for the treatment of cardiac arrest was first suggested in the literature in 1896 when Austrian scientist Dr. R. Gottlieb described the vasopressor epinephrine as an "infusion of a solution of suprarenal extract [that] would restore circulation when the blood pressure had been lowered to unrecordable levels by chloral hydrate."[40] Modern interest in vasopressors as a treatment for cardiac arrest stem mostly from canine studies performed in the 1960s by anesthesiologists Dr. John W. Pearson and Dr. Joseph Stafford Redding in which they demonstrated improved outcomes with the use of adjunct intracardiac epinephrine injection during resuscitation attempts after induced cardiac arrest.[40] Also contributing to the idea that vasopressors may be useful treatments in cardiac arrest are studies performed in the early to mid 1990's that found significantly higher levels of endogenous serum vasopressin in adults after successful resuscitation from out-of-hospital cardiac arrest compared to those who did not live.[41][42] Results of animal models have supported the use of either vasopressin or epinephrine in cardiac arrest resuscitation attempts, showing improved coronary perfusion pressure[43] and overall improvement in short-term survival as well as neurological outcomes.[44]

Vasopressin vs. epinephrine

Although both vasopressors, vasopressin and epinephrine differ in that vasopressin does not have direct effects on cardiac contractility as epinephrine does.[44] Thus, vasopressin is theorized to be of increased benefit over epinephrine in cardiac arrest due to its properties of not increasing myocardial and cerebral oxygen demands.[44] This idea has led to the advent of several studies searching for the presence of a clinical difference in benefit of these two treatment choices. Initial small studies demonstrated improved outcomes with vasopressin in comparison to epinephrine.[45] However, subsequent studies have not all been in agreement. Several randomized controlled trials have been unable to reproduce positive results with vasopressin treatment in both return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC) and survival to hospital discharge,[45][46][47][48] including a systematic review and meta-analysis completed in 2005 that found no evidence of a significant difference with vasopressin in five studied outcomes.[43]

Vasopressin and epinephrine vs. epinephrine alone

There is no current evidence of significant survival benefit with improved neurological outcomes in patients given combinations of both epinephrine and vasopressin during cardiac arrest.[43][46][49][50] A systematic review from 2008 did, however, find one study that showed a statistically significant improvement in ROSC and survival to hospital discharge with this combination treatment; unfortunately, those patients that survived to hospital discharge had overall poor outcomes and many suffered permanent, severe neurological damage.[48][50] A more recently published clinical trial out of Singapore has shown similar results, finding combination treatment to only improve the rate of survival to hospital admission, especially in the subgroup analysis of patients with longer "collapse to emergency department" arrival times of 15 to 45 minutes.[51]

2010 American Heart Association Guidelines

The 2010 American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care recommend the consideration of vasopressor treatment in the form of epinephrine in adults with cardiac arrest (Class IIb, LOE A recommendation).[52] Due to the absence of evidence that vasopressin administered instead of or in addition to epinephrine has significant positive outcomes, the guidelines do not currently contain vasopressin as a part of the cardiac arrest algorithms.[52] It does, however, allow for one dose of vasopressin to replace either the first or second dose of epinephrine in the treatment of cardiac arrest (Class IIb, LOE A recommendation).[52] 2015 AHA GUIDELINES VASOPRESSIN has been removed from the 2015 AHA GUIDELINES Update for CPR and ECC.

Surgery for congenital heart disease

Over the past decade, vasopressin has become an important part of the armamentarium available to bedside clinicians managing hemodynamic instability in neonates and older children recovering from cardiac surgery.[53][54][55][56][57][58] There is evidence that some children recovering from cardiac surgery have relative vasopressin deficiency, such that their endogenous plasma concentrations of arginine vasopressin are lower than what would be expected in this clinical setting.[54][55][58] Though low endogenous vasopressin concentrations in and of themselves do not cause hemodynamic instability, neonates and children recovering from cardiac surgery who develop hemodynamic instability and have low endogenous vasopressin concentrations are optimal candidates for this surgery. Unfortunately, measurement of endogenous vasopressin concentration is time consuming and cumbersome, and not practical for bedside application. Copeptin, a more stable and easily measured product of pro-AVP processing, may be a means of identifying patients with low endogenous vasopressin concentrations.[55] Further research is needed. Also, systemic corticosteroids have been shown to suppress endogenous vasopressin production and release.[58] Neonates and children recovering from cardiac surgery who are receiving systemic corticosteroid therapy may also be optimal candidates for vasopressin therapy should hemodynamic instability be present.

Vasopressin receptor inhibition

A vasopressin receptor antagonist is an agent that interferes with action at the vasopressin receptors. They can be used in the treatment of hyponatremia.[59]

See also

- Syndrome of Inappropriate Antidiuretic Hormone secretion (SIADH)

- Oxytocin

- Sexual motivation and hormones

- Vasopressin receptor

- Vasopressin receptor antagonists

- Copeptin

References

- ↑ "Drugs that physically interact with argipressin view/edit references on wikidata".

- ↑ "Human PubMed Reference:".

- ↑ "Mouse PubMed Reference:".

- ↑ Anderson DA (2012). Dorland's Illustrated Medical Dictionary (32nd ed.). Elsevier. ISBN 978-1-4160-6257-8.

- ↑ Marieb E (2014). Anatomy & physiology. Glenview, IL: Pearson Education, Inc. ISBN 978-0-321-86158-0.

- ↑ Caldwell HK, Young WS III (2006). "Oxytocin and Vasopressin: Genetics and Behavioral Implications" (PDF). In Lajtha A, Lim R. Handbook of Neurochemistry and Molecular Neurobiology: Neuroactive Proteins and Peptides (3rd ed.). Berlin: Springer. pp. 573–607. ISBN 0-387-30348-0.

- 1 2 3 Babar SM (October 2013). "SIADH associated with ciprofloxacin". The Annals of Pharmacotherapy. 47 (10): 1359–63. doi:10.1177/1060028013502457. PMID 24259701.

- ↑ Nielsen S, Chou CL, Marples D, Christensen EI, Kishore BK, Knepper MA (February 1995). "Vasopressin increases water permeability of kidney collecting duct by inducing translocation of aquaporin-CD water channels to plasma membrane". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 92 (4): 1013–7. doi:10.1073/pnas.92.4.1013. PMC 42627

. PMID 7532304.

. PMID 7532304. - ↑ Insel TR (March 2010). "The challenge of translation in social neuroscience: a review of oxytocin, vasopressin, and affiliative behavior". Neuron. 65 (6): 768–79. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2010.03.005. PMC 2847497

. PMID 20346754.

. PMID 20346754. - 1 2 Lim MM, Young LJ (2004). "Vasopressin-dependent neural circuits underlying pair bond formation in the monogamous prairie vole". Neuroscience. 125 (1): 35–45. doi:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2003.12.008. PMID 15051143.

- ↑ Chapman, MBBS, PhD, University of Adelaide, Royal Adelaide Hospital, Ian. "Central Diabetes Insipidus".

- ↑ Sands JM, Blount MA, Klein JD (2011). "Regulation of renal urea transport by vasopressin". Transactions of the American Clinical and Climatological Association. 122: 82–92. PMC 3116377

. PMID 21686211.

. PMID 21686211. - ↑ Knepper MA, Kim GH, Fernández-Llama P, Ecelbarger CA (March 1999). "Regulation of thick ascending limb transport by vasopressin". Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 10 (3): 628–34. PMID 10073614.

- ↑ Earley LE, Sanders CA (March 1959). "The effect of changing serum osmolality on the release of antidiuretic hormone in certain patients with decompensated cirrhosis of the liver and low serum osmolality". The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 38 (3): 545–50. doi:10.1172/jci103832. PMC 293190

. PMID 13641405.

. PMID 13641405. - ↑ Liu Z, Yan SF, Walker JR, Zwingman TA, Jiang T, Li J, Zhou Y (2007). "Study of gene function based on spatial co-expression in a high-resolution mouse brain atlas". BMC Systems Biology. 1: 19. doi:10.1186/1752-0509-1-19. PMC 1863433

. PMID 17437647.

. PMID 17437647. - ↑ Forsling ML, Montgomery H, Halpin D, Windle RJ, Treacher DF (May 1998). "Daily patterns of secretion of neurohypophysial hormones in man: effect of age". Experimental Physiology. 83 (3): 409–18. PMID 9639350.

- ↑ Goland RS, Wardlaw SL, MacCarter G, Warren WB, Stark RI (August 1991). "Adrenocorticotropin and cortisol responses to vasopressin during pregnancy". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 73 (2): 257–61. doi:10.1210/jcem-73-2-257. PMID 1649836.

- ↑ Ma S, Shipston MJ, Morilak D, Russell JA (March 2005). "Reduced hypothalamic vasopressin secretion underlies attenuated adrenocorticotropin stress responses in pregnant rats". Endocrinology. 146 (3): 1626–37. doi:10.1210/en.2004-1368. PMID 15591137.

- ↑ Toufexis DJ, Tesolin S, Huang N, Walker C (October 1999). "Altered pituitary sensitivity to corticotropin-releasing factor and arginine vasopressin participates in the stress hyporesponsiveness of lactation in the rat". Journal of Neuroendocrinology. 11 (10): 757–64. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2826.1999.00381.x. PMID 10520124.

- ↑ Wiltshire T, Maixner W, Diatchenko L (December 2011). "Relax, you won't feel the pain". Nature Neuroscience. 14 (12): 1496–7. doi:10.1038/nn.2987. PMID 22119947.

- ↑ Young LJ (October 2009). "The neuroendocrinology of the social brain". Frontiers in Neuroendocrinology. 30 (4): 425–8. doi:10.1016/j.yfrne.2009.06.002. PMID 19596026.

- ↑ Walum H, Westberg L, Henningsson S, Neiderhiser JM, Reiss D, Igl W, Ganiban JM, Spotts EL, Pedersen NL, Eriksson E, Lichtenstein P (September 2008). "Genetic variation in the vasopressin receptor 1a gene (AVPR1A) associates with pair-bonding behavior in humans". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 105 (37): 14153–6. doi:10.1073/pnas.0803081105. PMC 2533683

. PMID 18765804.

. PMID 18765804. - ↑ Pitkow LJ, Sharer CA, Ren X, Insel TR, Terwilliger EF, Young LJ (September 2001). "Facilitation of affiliation and pair-bond formation by vasopressin receptor gene transfer into the ventral forebrain of a monogamous vole". The Journal of Neuroscience. 21 (18): 7392–6. PMID 11549749.

- ↑ Wang XM, Dayanithi G, Lemos JR, Nordmann JJ, Treistman SN (November 1991). "Calcium currents and peptide release from neurohypophysial terminals are inhibited by ethanol". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 259 (2): 705–11. PMID 1941619.

- 1 2 Matsukawa T, Miyamoto T (March 2011). "Angiotensin II-stimulated secretion of arginine vasopressin is inhibited by atrial natriuretic peptide in humans". American Journal of Physiology. Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology. 300 (3): R624–9. doi:10.1152/ajpregu.00324.2010. PMID 21123762.

- ↑ Salata RA, Jarrett DB, Verbalis JG, Robinson AG (March 1988). "Vasopressin stimulation of adrenocorticotropin hormone (ACTH) in humans. In vivo bioassay of corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF) which provides evidence for CRF mediation of the diurnal rhythm of ACTH". The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 81 (3): 766–74. doi:10.1172/JCI113382. PMC 442524

. PMID 2830315.

. PMID 2830315. - ↑ Bielsky IF, Hu SB, Szegda KL, Westphal H, Young LJ (March 2004). "Profound impairment in social recognition and reduction in anxiety-like behavior in vasopressin V1a receptor knockout mice". Neuropsychopharmacology. 29 (3): 483–93. doi:10.1038/sj.npp.1300360. PMID 14647484.

- ↑ Wersinger SR, Caldwell HK, Martinez L, Gold P, Hu SB, Young WS (August 2007). "Vasopressin 1a receptor knockout mice have a subtle olfactory deficit but normal aggression". Genes, Brain, and Behavior. 6 (6): 540–51. doi:10.1111/j.1601-183X.2006.00281.x. PMID 17083331.

- ↑ Lolait SJ, Stewart LQ, Jessop DS, Young WS, O'Carroll AM (February 2007). "The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis response to stress in mice lacking functional vasopressin V1b receptors". Endocrinology. 148 (2): 849–56. doi:10.1210/en.2006-1309. PMC 2040022

. PMID 17122081.

. PMID 17122081. - ↑ Wersinger SR, Kelliher KR, Zufall F, Lolait SJ, O'Carroll AM, Young WS (December 2004). "Social motivation is reduced in vasopressin 1b receptor null mice despite normal performance in an olfactory discrimination task". Hormones and Behavior. 46 (5): 638–45. doi:10.1016/j.yhbeh.2004.07.004. PMID 15555506.

- ↑ Kanwar S, Woodman RC, Poon MC, Murohara T, Lefer AM, Davenpeck KL, Kubes P (October 1995). "Desmopressin induces endothelial P-selectin expression and leukocyte rolling in postcapillary venules". Blood. 86 (7): 2760–6. PMID 7545469.

- ↑ Kaufmann JE, Oksche A, Wollheim CB, Günther G, Rosenthal W, Vischer UM (July 2000). "Vasopressin-induced von Willebrand factor secretion from endothelial cells involves V2 receptors and cAMP". The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 106 (1): 107–16. doi:10.1172/JCI9516. PMC 314363

. PMID 10880054.

. PMID 10880054. - ↑ Burtis CA, Ashwood ER, Bruns DE (2012). Tietz Textbook of Clinical Chemistry and Molecular Diagnostics (5th ed.). Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 1833. ISBN 978-1-4557-5942-2.

- ↑ Donaldson D (2014). "Polyuria and Disorders of Thirst". In Williams DL, Marks V. Scientific Foundations of Biochemistry in Clinical Practice (2nd ed.). Butterworth-Heinemann. pp. 76–102. ISBN 978-1-4831-9362-5.

- ↑ Li C, Wang W, Summer SN, Westfall TD, Brooks DP, Falk S, Schrier RW (February 2008). "Molecular mechanisms of antidiuretic effect of oxytocin". Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 19 (2): 225–32. doi:10.1681/ASN.2007010029. PMC 2396735

. PMID 18057218.

. PMID 18057218. - ↑ Joo KW, Jeon US, Kim GH, Park J, Oh YK, Kim YS, Ahn C, Kim S, Kim SY, Lee JS, Han JS (October 2004). "Antidiuretic action of oxytocin is associated with increased urinary excretion of aquaporin-2". Nephrology, Dialysis, Transplantation. 19 (10): 2480–6. doi:10.1093/ndt/gfh413. PMID 15280526.

- ↑ Acher R, Chauvet J (July 1995). "The neurohypophysial endocrine regulatory cascade: precursors, mediators, receptors, and effectors". Frontiers in Neuroendocrinology. 16 (3): 237–89. doi:10.1006/frne.1995.1009. PMID 7556852.

- 1 2 3 Verbalis JG, Goldsmith SR, Greenberg A, Schrier RW, Sterns RH (November 2007). "Hyponatremia treatment guidelines 2007: expert panel recommendations". The American Journal of Medicine. 120 (11 Suppl 1): S1–21. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2007.09.001. PMID 17981159.

- ↑ Baum S, Nusbaum M, Tumen HJ (1970). "The control of gastrointestinal hemorrhage by selective mesenteric infusion of pitressin". Gastroenterology. 58: 926.

- 1 2 Pearson JW, Redding JS (Sep–Oct 1963). "THE ROLE OF EPINEPHRINE IN CARDIAC RESUSCITATION". Anesthesia and Analgesia. 42 (5): 599–606. doi:10.1213/00000539-196309000-00022. PMID 14061643.

- ↑ Lindner KH, Strohmenger HU, Ensinger H, Hetzel WD, Ahnefeld FW, Georgieff M (October 1992). "Stress hormone response during and after cardiopulmonary resuscitation". Anesthesiology. 77 (4): 662–8. doi:10.1097/00000542-199210000-00008. PMID 1329579.

- ↑ Lindner KH, Haak T, Keller A, Bothner U, Lurie KG (February 1996). "Release of endogenous vasopressors during and after cardiopulmonary resuscitation". Heart. 75 (2): 145–50. doi:10.1136/hrt.75.2.145. PMC 484250

. PMID 8673752.

. PMID 8673752. - 1 2 3 Aung K, Htay T (January 2005). "Vasopressin for cardiac arrest: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Archives of Internal Medicine. 165 (1): 17–24. doi:10.1001/archinte.165.1.17. PMID 15642869.

- 1 2 3 Williamson K, Breed M, Alibertis K, Brady WJ (February 2012). "The impact of the code drugs: cardioactive medications in cardiac arrest resuscitation". Emergency Medicine Clinics of North America. 30 (1): 65–75. doi:10.1016/j.emc.2011.09.008. PMID 22107975.

- 1 2 Lee SW (August 2011). "Drugs in resuscitation: an update". Singapore Medical Journal. 52 (8): 596–602. PMID 21879219.

- 1 2 Callaway CW, Hostler D, Doshi AA, Pinchalk M, Roth RN, Lubin J, Newman DH, Kelly LJ (November 2006). "Usefulness of vasopressin administered with epinephrine during out-of-hospital cardiac arrest". The American Journal of Cardiology. 98 (10): 1316–21. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2006.06.022. PMID 17134621.

- ↑ Stiell IG, Hébert PC, Wells GA, Vandemheen KL, Tang AS, Higginson LA, Dreyer JF, Clement C, Battram E, Watpool I, Mason S, Klassen T, Weitzman BN (July 2001). "Vasopressin versus epinephrine for inhospital cardiac arrest: a randomised controlled trial". Lancet. 358 (9276): 105–9. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(01)05328-4. PMID 11463411.

- 1 2 Wenzel V, Krismer AC, Arntz HR, Sitter H, Stadlbauer KH, Lindner KH (January 2004). "A comparison of vasopressin and epinephrine for out-of-hospital cardiopulmonary resuscitation". The New England Journal of Medicine. 350 (2): 105–13. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa025431. PMID 14711909.

- ↑ Gueugniaud PY, David JS, Chanzy E, Hubert H, Dubien PY, Mauriaucourt P, Bragança C, Billères X, Clotteau-Lambert MP, Fuster P, Thiercelin D, Debaty G, Ricard-Hibon A, Roux P, Espesson C, Querellou E, Ducros L, Ecollan P, Halbout L, Savary D, Guillaumée F, Maupoint R, Capelle P, Bracq C, Dreyfus P, Nouguier P, Gache A, Meurisse C, Boulanger B, Lae C, Metzger J, Raphael V, Beruben A, Wenzel V, Guinhouya C, Vilhelm C, Marret E (July 2008). "Vasopressin and epinephrine vs. epinephrine alone in cardiopulmonary resuscitation". The New England Journal of Medicine. 359 (1): 21–30. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0706873. PMID 18596271.

- 1 2 Sillberg VA, Perry JJ, Stiell IG, Wells GA (December 2008). "Is the combination of vasopressin and epinephrine superior to repeated doses of epinephrine alone in the treatment of cardiac arrest-a systematic review". Resuscitation. 79 (3): 380–6. doi:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2008.07.020. PMID 18951676.

- ↑ Ong ME, Tiah L, Leong BS, Tan EC, Ong VY, Tan EA, Poh BY, Pek PP, Chen Y (August 2012). "A randomised, double-blind, multi-centre trial comparing vasopressin and adrenaline in patients with cardiac arrest presenting to or in the Emergency Department". Resuscitation. 83 (8): 953–60. doi:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2012.02.005. PMID 22353644.

- 1 2 3 Neumar RW, Otto CW, Link MS, Kronick SL, Shuster M, Callaway CW, Kudenchuk PJ, Ornato JP, McNally B, Silvers SM, Passman RS, White RD, Hess EP, Tang W, Davis D, Sinz E, Morrison LJ (November 2010). "Part 8: adult advanced cardiovascular life support: 2010 American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care". Circulation. 122 (18 Suppl 3): S729–67. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.970988. PMID 20956224.

- ↑ Mastropietro CW, Clark JA, Delius RE, Walters HL, Sarnaik AP (September 2008). "Arginine vasopressin to manage hypoxemic infants after stage I palliation of single ventricle lesions". Pediatric Critical Care Medicine. 9 (5): 506–10. doi:10.1097/pcc.0b013e3181849ce0. PMID 18679141.

- 1 2 Mastropietro CW, Rossi NF, Clark JA, Chen H, Walters H, Delius R, Lieh-Lai M, Sarnaik AP (October 2010). "Relative deficiency of arginine vasopressin in children after cardiopulmonary bypass". Critical Care Medicine. 38 (10): 2052–8. doi:10.1097/ccm.0b013e3181eed91d. PMID 20683257.

- 1 2 3 Mastropietro CW, Mahan M, Valentine KM, Clark JA, Hines PC, Walters HL, Delius RE, Sarnaik AP, Rossi NF (December 2012). "Copeptin as a marker of relative arginine vasopressin deficiency after pediatric cardiac surgery". Intensive Care Medicine. 38 (12): 2047–54. doi:10.1007/s00134-012-2731-9. PMID 23093248.

- ↑ Mastropietro CW, Davalos MC, Seshadri S, Walters HL, Delius RE (June 2013). "Clinical response to arginine vasopressin therapy after paediatric cardiac surgery". Cardiology in the Young. 23 (3): 387–93. doi:10.1017/S1047951112000996. PMID 22805534.

- ↑ Davalos MC, Barrett R, Seshadri S, Walters HL, Delius RE, Zidan M, Mastropietro CW (March 2013). "Hyponatremia during arginine vasopressin therapy in children following cardiac surgery". Pediatric Critical Care Medicine. 14 (3): 290–7. doi:10.1097/pcc.0b013e3182720473. PMID 23392370.

- 1 2 3 Mastropietro CW, Miletic K, Chen H, Rossi NF (December 2014). "Effect of corticosteroids on arginine vasopressin after pediatric cardiac surgery". Journal of Critical Care. 29 (6): 982–6. doi:10.1016/j.jcrc.2014.07.007. PMID 25092616.

- ↑ Palm C, Pistrosch F, Herbrig K, Gross P (July 2006). "Vasopressin antagonists as aquaretic agents for the treatment of hyponatremia". The American Journal of Medicine. 119 (7 Suppl 1): S87–92. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2006.05.014. PMID 16843091.

Further reading

- Rector FC, Brenner BM (2004). Brenner & Rector's the kidney (7th ed.). Philadelphia: Saunders. ISBN 978-0-7216-0164-9.

- Mastropietro CW (May 2013). "Arginine vasopressin and paediatric cardiovascular surgery". OA Critical Care. 1 (1): 7. doi:10.13172/2052-9309-1-1-680.