Anti-union violence

Anti-union violence is physical force intended to harm union officials, union organizers, union members, union sympathizers, or their families. It is most commonly used either during union organizing efforts, or during strikes. The aim most often is to prevent a union from forming, to destroy an existing union, or to reduce the effectiveness of a union or a particular strike action. If strikers prevent people or goods to enter or leave a workplace, violence may be used to allow people and goods to pass the picket line.

Violence against unions may be isolated, or may occur as part of a campaign that includes spying, intimidation, impersonation, disinformation, and sabotage.[1] Violence in labor disputes may be the result of unreasonable polarization, or miscalculation. It may be willful and provoked, or senseless and tragic. On some occasions, violence in labor disputes may be purposeful and calculated,[2] for example the hiring and deployment of goon squads to assault strikers.

Incidents of violence during periods of labor unrest are sometimes perceived differently by different parties. It is sometimes a challenge to ascertain the truth about labor-related violence, and incidents of violence committed by, or in the name of, unions or union workers have occurred as well.

History

The practice of workers organizing, and meeting resistance for organizing, dates to antiquity.[3] The first known individual killed by authorities for labor activities is likely Cinto Brandini, executed with nine others in 1345 Florence for attempting to organize woolcombers.[4]

According to a study in 1969, the United States has had the bloodiest and most violent labor history of any industrial nation in the world.[5] Mass labor violence in the U.S. peaked in the early 20th century and has largely subsided since the 1940s. But the deadly suppression of labor unions on a large scale persists into the new century, in the 2012 Marikana killings in South Africa, in the ongoing assassinations of trade union members in Colombia, and the South Korean government's response to Korean Confederation of Trade Unions protests.[6]

Causes

Since unions are organized to achieve collective bargaining power to begin with, most union conflicts have been motivated primarily by economic issues (wages, working hours, safety conditions, work rules, etc.),[7] and have engaged antagonists (employers, hired strikebreakers, replacement workers, local law enforcement) with economic goals in mind. In some instances, however, other causes emerge.

Race

The 1887 Thibodaux massacre in Louisiana, the 1899 Pana riot in southern Illinois, and the 1911 Queen & Crescent killings in Kentucky and Tennessee are three examples of deliberate campaigns of murder against organized black workers in the American south, the first committed by landowners, the other two by white competitors.

In South Africa the 1922 Rand Rebellion also had underlying racial causes, taking on the slogan "Workers of the world, unite and fight for a white South Africa!",[8] before their strike grew to a small-scale rebellion at the cost of 200 lives. The behavior of South African police in the 1946 African Mine Workers' Union strike is said to have led to the formation of the Northern Rhodesian African Mineworkers' Union in 1949 as a cornerstone of the anti-apartheid movement.[9]

Political power

As with race, for some incidents there is no clear distinction between anti-union violence and political suppression. Polish labor unions were centrally involved in workers’ uprisings and/or general strikes that challenged the sitting governments in 1905, 1923, and 1937. In a similar way the strike of Asturian miners in 1934, put down by right-wing Spanish government forces with great loss of life, amounted to an insurrection through work stoppage, not an economic labor action. Unions continued to play a political and military role in the subsequent Spanish Civil War.

Along with Franco in Spain, other totalitarian regimes in Europe brought their labor unions under government control, violently when necessary. After coming to power as chancellor in January 1933, Adolf Hitler declared May Day a national holiday, then on May 2, 1933 unexpectedly moved to outlaw labor unions as part of the Nazi "synchronization" process. Major unions such as the Allgemeiner Deutscher Gewerkschaftsbund were raided that day, their accounts seized, and their leaders (Gustav Schiefer, Wilhelm Leuschner, Erich Luebbe) arrested and sent to concentration camps. (The bodies of four murdered trade union officials in Duisburg were only found a year later, in April 1934.)[10] Every worker in the nation was then compelled to join the single party-controlled sham union German Labour Front. Similar coercive violence was exercised against labor unions in conquered nations, as in the Netherlands in 1941.[11]

Types of violence

Some anti-union violence appears to be random, such as an incident during the 1912 textile strike in Lawrence, Massachusetts, in which a police officer fired into a crowd of strikers, killing Anna LoPizzo.[12]

Anti-union violence may be used as a means to intimidate others, as in the hanging of union organizer Frank Little from a railroad trestle in Butte, Montana. A note was pinned to his body which said, "Others Take Notice! First And Last Warning!" The initial of the last names of seven well-known union activists in the Butte area were on the note, with the "L" for Frank Little circled.[13][14]

Anti-union violence may be abrupt and unanticipated. Three years after Frank Little was lynched, a strike by Butte miners was suppressed with gunfire when deputized mine guards suddenly fired upon unarmed picketers in the Anaconda Road Massacre. Seventeen were shot in the back as they tried to flee, and one man died.[15]

Other anti-union violence may seem orchestrated, as in 1914 when mine guards and the state militia fired into a tent colony of striking miners in Colorado, an incident that came to be known as the Ludlow Massacre.[16] During that strike, the company hired the Baldwin Felts agency, which built an armored car so their agents could approach the strikers' tent colonies with impunity. The strikers called it the "Death Special". At the Forbes tent colony,

"[The Death Special] opened fire, a protracted spurt that sent some six hundred bullets tearing through the thin tents. One of the shots struck miner Luka Vahernik, fifty, in the head, killing him instantly. Another striker, Marco Zamboni, eighteen ... suffered nine bullet wounds to his legs... One tent was later found to have about 150 bullet holes..."[17]

Sometimes, there is simultaneous violence on both sides. In an auto workers strike organised by Victor Reuther and others in 1937, "[u]nionists assembled rocks, steel hinges, and other objects to throw at the cops, and police organized tear gas attacks and mounted charges."[18]

There have been cases where violence has been perpetrated or encouraged by agents of management, intending it to be blamed on the union.[19]

Violence by country

Europe

- Belgium

- the Belgian general strike of 1902 was led by the coal miners of Liège, lasting 10 to 20 days and killing about 12

- Russia

- in the Lena massacre hundreds of striking goldfield workers were killed by tsarist government forces in northeast Siberia near the Lena River on 17 April [O.S. 4 April] 1912

- United Kingdom

- on 17 May 1869, a labor action of Welsh colliers (forcibly delivering the mine's new operator to the police station) developed into The Mold Riot, a confrontation between a mob of 1500 workers and citizens, versus King's Own Royal Regiment. When pelted with stones, the King's Own fired into the crowd, killing four

North America

- Canada

- With casualties as one indication of its national history, a union pamphlet published in 2006 counted a total of 24 "Canadian Labour Martyrs" since 1903, a number that includes Joseph Mairs of the Vancouver Island War of 1912-14, coal miner Albert Goodwin killed in 1918, miner Bill Davis of Nova Scotia (namesake of the William Davis Miners' Memorial Day), and the 1929 case of Rosvall and Voutilainen in Thunder Bay, Ontario.[20]

Rosvall and Voutilainen were murdered for their pro-union efforts resulting in the authorities in Thunder Bay conducting a major cover up in an attempt to conceal the truth. Thunder Bay remains a hot bed of anti-union violence against pro-union individuals resulting in Thunder Bay being labelled the Capital of Anti-union Violence of Canada.

- United States

- Victor Reuther, a leader of the United Auto Workers in Detroit, survived an assassination attempt in 1949, with the loss of his right eye.[21]

- In 1978, William Anthony "Tony" Boyle, President of the United Mine Workers, was tried and found guilty of the 1969 murder of fellow United Mine Workers challenger Joseph Yablonski.[22]

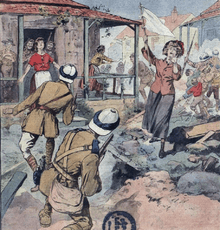

- Mexico

- the Cananea strike of organized mine workers in June 1906, and the Río Blanco strike of unionized textile workers in January 1907, became two linked symbols of the corruption and civil repression of the administration of Mexican president Porfirio Díaz. They became "household words for hundreds of thousands of Mexicans".[23]

Central and South America

- Argentina

- approximately 1,500 striking rural workers were shot and killed by the Argentine Army in the Patagonia Uprising between 1920 and 1922

- Bolivia

- government forces killed at least 19 striking mine workers in the Catavi Massacre of December 1942; the workers themselves counted 400 dead

- popular protests against the November 1, 1979 coup d'état of Alberto Natusch Busch, protests led by the Central Obrera Boliviana (COB) trade union confederation, were met with violence from the military. Perhaps 100 were killed, but the new government was overthrown within two weeks.[24]

- Chile

- the Santa María School massacre was a massacre of striking nitrate miners, with wives and children, committed by the Chilean Army in Iquique, Chile on December 21, 1907. The number of victims has been estimated at 2,000

- Colombia

- see main article Trade unions in Colombia

- Colombia has been identified as one of the most hazardous for present-day labor unionists.[25] According to the International Trade Union Confederation, over 2800 unionists were killed between 1986 and April 2010.[26]

- The Banana massacre, 1929

- Isidro Gil, a leader of the National Union of Food Industry Workers at the Bogotá, Colombia bottling plant of the Coca-Cola company who was shot dead at the plant on December 5, 1996. Four other leaders of the union have been killed since 1994, as have other union leaders in Colombia.

- El Salvador

- Estimates of the number of labor union members killed in the four first years of the Salvadoran Civil War (1979-1983) range from 3,000 to 8,000.[27] The 2004 murder of a visiting Teamsters organizer from New Jersey brought international attention to the country's "long record of hostility to union labor".[28]

- Venezuela

- As of 2010, some 75 union organizers and union members had been killed in the prior two years, according to figures compiled by the Catholic Church. New unions flourishing under the Chavez administration challenged established unions for lucrative memberships. One common tactic was public assassination.[29]

Africa

- South Africa

- the 1922 Rand Rebellion expanded from a strike into a small-scale rebellion at the cost of 200 lives, and the events of the 1946 African Mine Workers' Union strike indirectly led to the development of the anti-apartheid movement.[30]

Asia

- Cambodia

- Chea Vichea, leader of the Free Trade Union of Workers of the Kingdom of Cambodia (FTUWKC) was shot in the head and chest while reading a newspaper at a kiosk in Phnom Penh on January 22, 2004.[31] He had been dismissed by the INSM Garment Factory (located in the Chum Chao District of Phnom Penh), as a reprisal for helping to establish a trade union at the company.

- India

- Shankar Guha Niyogi, a leader of the Mukti Morcha union movement in the Indian state of Chhattisgarh was killed in Bhilai, on September 27, 1991,[32] allegedly by a hired assassin, in the middle of a major dispute about the regularisation of workers' contracts in the steel and engineering industries. The alleged assassin and two industrialists were convicted of his murder but released on appeal; their release is itself now subject to appeal.

Australasia

- Australia

- a striking stevedove was killed by police in the 1919 Fremantle Wharf riot, Fremantle, Western Australia

- one striking union worker was killed outright, and forty wounded by gunfire, when police shot into a crowd in the 1929 Rothbury riot, New South Wales, described as "the bloodiest event in national industrial history."[33]

- New Zealand

- Only three people have been killed in New Zealand's industrial history: Fred Evans, killed in 1912 in the Waihi miners' strike, Christine Clarke, the wife of a picketing worker struck by a car on New Year's Eve 1999,[34] and the victim of a suitcase bomb was left in the foyer of the Trades Hall in Wellington, 27 March 1984.[35] The Trades Hall was the headquarters of a number of trade unions, and it is most commonly assumed that they were the target of the bombing, although other theories have been put forward. Ernie Abbott, the building's caretaker, was killed when he attempted to move the suitcase, which is believed to have contained three sticks of gelignite triggered by a mercury switch.[36] To this day, the perpetrator has never been identified. Those elements of the New Zealand Police responsible for preventing and investigating such crimes were headquartered in the building across the street.

See also

References

- ↑ Robert Michael Smith, From Blackjacks To Briefcases — A History of Commercialized Strikebreaking and Unionbusting in the United States, 2003, p. 87

- ↑ Robert Hunter, Violence and the labor movement, Macmillan, 1914 (1919 version), page 318

- ↑ John Romer, Ancient Lives; the story of the Pharaoh's Tombmakers. London: Phoenix Press, 1984, pp. 116-123 See also E.F. Wente, "A letter of complaint to the Vizier To", in Journal of Near Eastern Studies, 20, 1961 and W.F. Edgerton , "The strikes in Ramses III's Twenty-ninth year", Journal of Near Eastern Studies, 10, 1951.

- ↑ James C. Docherty, Sjaak van der Velden (2012). Historical Dictionary of Organized Labor. Scarecrow Press. p. xxv. Retrieved 18 April 2016.

- ↑ Philip Taft and Philip Ross, "American Labor Violence: Its Causes, Character, and Outcome," The History of Violence in America: A Report to the National Commission on the Causes and Prevention of Violence, ed. Hugh Davis Graham and Ted Robert Gurr, 1969.

- ↑ Lee, Hyun (12 November 2015). "South Korea Labor Strikes Back". Foreign Policy in Focus. Retrieved 18 April 2016.

- ↑ Lalor, John Joseph (1890). Cyclopaedia of Political Science, Political Economy, and of the Political History of the United States, Volume 3. C. E. Merrill & Company. p. 816. Retrieved 18 April 2016.

- ↑ "South Africa Conflict in the 1920s - Flags, Maps, Economy, Geography, Climate, Natural Resources, Current Issues, International Agreements, Population, Social Statistics, Political System". workmall.com.

- ↑ Naicker, M. P. "The African Miners' Strike of 1946".

- ↑ Gregor, Neil (2000). Nazism. Oxford University Press. p. 296. Retrieved 19 April 2016.

- ↑ Warmbrunn, Werner (1963). The Dutch Under German Occupation, 1940-1945. Stanford University Press. p. 136. Retrieved 19 April 2016.

- ↑ William Dudley Haywood, Autobiography of Big Bill Haywood, 1929, page 249

- ↑ Melvyn Dubofsky, We Shall Be All, A History of the Industrial Workers of the World, University of Illinois Press Abridged, 2000, pages 223-224

- ↑ Peter Carlson, Roughneck, The Life and Times of Big Bill Haywood, 1983, pages 17, 248-249

- ↑ Mary Murphy, Mining cultures: men, women, and leisure in Butte, 1914-41, University of Illinois Press, 1997, page 33

- ↑ Zinn, H. "The Ludlow Massacre", A People's History of the United States. pgs 346–349

- ↑ Scott Martelle, Blood Passion, Rutgers University Press, 2008, page 98

- ↑ Nelson Lichtenstein, Walter Reuther: the most dangerous man in Detroit, University of Illinois Press, 1997, page 101

- ↑ Robert Hunter, Violence and the labor movement, Macmillan, 1914 (1919 version), page 317

- ↑ "New Pamphlet of Canadian Labour Martyrs". International Workers of the World Canada. Retrieved 19 April 2016.

- ↑ Saxon, Wolfgang (2004-06-05). "Victor Reuther, Influential Labor Leader, Dies at 92". The New York Times. Retrieved 2009-04-14.

- ↑ George C. Kohn, The new encyclopedia of American scandal, Infobase Publishing, 2001 pages 53-54.

- ↑ The Cambridge History of Latin America, by Leslie Bethell, Cambridge University Press, 1986, page 66

- ↑ Asociación de Familiares de Detenidos Desaparecidos y Mártires por la Liberación Nacional (Bolivia), Fundación Solón, and Capítulo Boliviano de Derechos Humanos, Democracia y Desarrollo. Informe sobre las desapariciones forzadas en Bolivia. La Paz: ASOFAMD, 2008. p. 20

- ↑ ILO, 16 June 2000, Special ILO Representative for cooperation with Colombia to be appointed by Director-General

- ↑ International Trade Union Confederation, 11 June 2010, ITUC responds to the press release issued by the Colombian Interior Ministry concerning its survey

- ↑ Almeida, Paul D. (2008). Waves of Protest: Popular Struggle in El Salvador, 1925-2005. University of Minnesota Press. p. 179. Retrieved 18 May 2016.

- ↑ Sullivan, Kevin (2 December 2004). "Slaying of U.S. Labor Organizer Opens Old Wounds in El Salvador". Washington Post. Retrieved 18 May 2016.

- ↑ Ferero, Juan (2 August 2010). "In Venezuela, Rise of Labor Unions Turns Deadly". National Public Radio. Retrieved 15 May 2016.

- ↑ Naicker, M. P. "The African Miners' Strike of 1946".

- ↑ "Kingdom of Cambodia: The killing of trade unionist Chea Vichea". Amnesty International. 2004-12-03. Archived from the original on 15 April 2009. Retrieved 2009-04-14.

- ↑ "Now a Hero, Then a Hero". Tehelka. 2007-07-14. Retrieved 2009-04-14.

- ↑ Huxley, John (20 May 2006). "Deadly riot: record set straight". Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 17 April 2016.

- ↑ "Service to mark death of union 'martyr'". Manwatu Standard. 26 March 2014. Retrieved 18 April 2016.

- ↑ Talia Shadwell (2014-03-27). "Wellington's unsolved Trades Hall mystery". The Dominion Post.

- ↑ Minchin, William (2005)