Animal Man (comic book)

| Animal Man | |

|---|---|

|

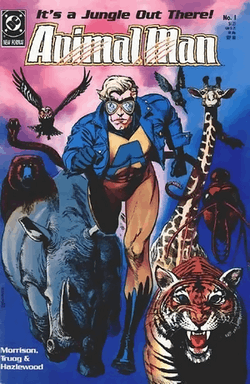

Cover to Animal Man #1. Art by Brian Bolland. | |

| Publication information | |

| Publisher |

DC Comics Vertigo |

| Schedule | Monthly |

| Format | Ongoing series |

| Genre | Postmodern, Horror, Superhero |

| Publication date |

(vol. 1) September 1988 – November 1995 (vol. 2) September 2011 – March 2014 |

| Number of issues |

(vol. 1): 89 and 1 Annual (vol. 2): 30 (#1–29 plus issue numbered 0) and 2 Annuals |

| Main character(s) | Animal Man |

| Creative team | |

| Creator(s) |

Grant Morrison Chas Truog |

Animal Man was a comic book ongoing series published by DC Comics starring the superhero Animal Man. The series is best known for the run by writer Grant Morrison from issue #1 to #26 with penciller Chas Truog who stayed on the series until #32. Almost all of the series' writers and artists were part of the British Invasion of comics.

Animal Man was innovative in its advocacy and for its use of themes including social consciousness (with a focus on animal rights), metaphysics, deconstruction of the superhero genre and comic book form, postmodernism, eccentric plot twists, explorations of cosmic spirituality and mysticism, the determination of apparent free will by a higher power, and manipulation of reality including quantum physics, unified field theory, time travel and metafictional technique. The series is well known for its frequently psychedelic and "off the wall" content.[1]

A majority of the series' cover art was done by Brian Bolland, often portraying intentionally unusual or shocking imagery with no text blurbs.

Grant Morrison would return to the character Animal Man in 52.

Publication history

Although the series was initially conceived as a four-issue limited series, it was upgraded into an ongoing series following strong sales.

The series was released in DC's high quality New Format, and was published without the Comics Code Authority seal of approval. When DC launched its Vertigo imprint in 1993, Animal Man was moved to the imprint beginning with issue #57.[1]

Grant Morrison's run (1988-1990)

Morrison developed several long-running plots, introducing mysteries, some of which were not explained until a year or two later. The title featured the protagonist both in and — increasingly — out of costume. Morrison made the title character an everyman figure living in a universe populated by superheroes, aliens, and fantastic technology. Buddy's wife Ellen, his son Cliff (9 years old at the beginning of the series), and his daughter Maxine (5 years old) featured prominently in most storylines, and his relationship with them, as husband, father, and provider, was an ongoing theme.

The series championed vegetarianism and animal rights, causes Morrison himself supported. In one issue, Buddy helps a band of self-confessed eco-terrorists save a pod of dolphins. Enraged at a fisherman's brutality, Buddy drops him into the ocean, intending for him to drown. Ironically, the man is saved by a dolphin.

Buddy fought several menaces, such as an ancient, murderous spirit that was hunting him; brutal, murderous alien Thanagarian warriors; and even the easily defeated red robots of an elderly villain who was tired of life. The series made deep, sometimes esoteric, reference to the entire DC canon, including B'wana Beast, Mirror Master, and Arkham Asylum.

Post-Morrison (1990-1993)

Following Morrison's run, Peter Milligan wrote a 6-issue story (#27-32) featuring several surreal villains and heroes, exploring questions about identity and quantum physics and utilizing the textual cut-up technique popularized by William S. Burroughs. Tom Veitch and Steve Dillon then took over for 18 issues (#33-50) in which Buddy returns to his work as a movie stuntman and explores mystical totemic aspects of his powers. Jamie Delano wrote 29 issues (#51-79) with Steve Pugh as artist, giving the series a more horror-influenced feel with a "suggested for mature readers" label on the cover.

Vertigo (1993-1995)

After Jamie Delano's first six issues, wherein, among other things, he killed off the central character of Buddy Baker, created the "Red" and resurrected Buddy as an "animal avatar" (analogous to the "Green" of Swamp Thing), the series became one of the charter titles of DC's new mature readers Vertigo imprint with #57, and its ties to the DC Universe became more tenuous. Vertigo was establishing itself as a distinct "mini-universe" with its own continuity, only occasionally interacting with the continuity of the regular DC Universe. The title evolved into a more horror-themed book, with Buddy eventually becoming a non-human animal god. The super-hero elements of the book were largely removed — since Buddy was reborn as a kind of animal elemental, and legally deceased, he discarded his costume, stopped associating with other heroes, and generally abandoned his crime-fighting role. He co-founded the Life Power Church of Maxine to further an environmentalist message, drifting along U.S. Route 66 to settle in Montana. Delano's final issue was #79, culminating in Buddy dying several more times.

Between issues #66 and #67, Delano also penned the Animal Man Annual #1, focusing on Buddy's daughter Maxine. It was the third part of Vertigo's attempt to create a crossover event titled "The Children's Crusade". This event ran across the Annuals of the five then-Vertigo titles – Animal Man, Swamp Thing, Black Orchid, The Books of Magic and Doom Patrol – book-ended by two Children's Crusade issues co-written by Neil Gaiman, and starring his Dead Boy Detectives.

A brief run by Jerry Prosser and Fred Harper (#80-89) featured a re-reborn Buddy as a white-haired shamanistic figure before the series was canceled after the 89th issue due to declining sales.

Return to DC (2011-2014)

The character returned to a new ongoing series at DC Comics as part of The New 52, following the Flashpoint storyline, with the initial creative team being writer Jeff Lemire and artists Travel Foreman and Dan Green.[2][3] The series follows Buddy and his family as his daughter Maxine begins to display powers of necromancy-based animal control.[4] Buddy is then forced to go on a journey to discover the source of this power and his own. He finds it in a life force known as the "Red", the animal counterpart to the "Green" from Swamp Thing. Much like the Green, there have been multiple creatures chosen to represent the Red over the years; a few became evil and became what is known as the "Rot".[5] This led into a crossover between Swamp Thing and Frankenstein: Agent of S.H.A.D.E. titled "Rotworld".

"Nature of reality" as a theme

During his run on the title, Morrison consistently manipulated and deconstructed the fourth wall — the imaginary barrier separating the reader from the setting of the story which also extends to the characters and their creators. One visual expression of this theme was to present characters in a state of partial erasure — often juxtaposing the artist's pencil drafts with the finished art. Additionally, some characters become aware that they are being viewed by a vast audience, and are able to interact with the borders of the panels on the page. The series notably contained overt references to the various Earths of the pre-Crisis DC Multiverse.

Issue #5, "The Coyote Gospel," features Crafty, a thinly disguised Wile E. Coyote (of the Road Runner cartoons).[1] Weary of the endless cycle of violence which he and his cartoon compatriots are subject to, Crafty appeals to his cartoonist-creator. A bargain is struck: he can end the violence only by willingly being condemned to leave his cartoon world, entering Animal Man's "comic" world instead. The issue concludes with a series of "pull-back" shots beginning with a close-up of Crafty's bleeding body (and white blood), culminating with a panel depicting the cartoonist's immense hand, coloring Crafty's blood with red paint. The issue is partly a religious allegory and partly a juxtaposition of the various layers of reality: cartoon to comic book, comic book to real life. It was nominated for an Eisner Award for Best Single Issue of 1989.

The culmination of this self-referentiality is Animal Man's eventual discovery that all of the inhabitants of the DC universe are fictional characters. He even meets Grant Morrison, the callous "god" who controls his life.

Buddy suffers a tragedy when his wife and children are brutally murdered while he is away on a case.[6] Buddy tracks down the killers to exact vengeance. His search leads him into a comic book Limbo, a plane of residence for characters who are not actively written about. Animal Man ultimately confronts his writer in issue #26, and his family is restored to life, as Morrison finds he cannot justify keeping them dead simply for the sake of "realism".[7] (See comic book death)

Grant Morrison also explains to Buddy that he writes him as a vegetarian only because he himself is a vegetarian too, and every trait Baker possesses could be changed at a whim. "They might do the obvious and go for shock by turning you into a meat-eater," Morrison says. In issue #27, the first of Peter Milligan's run, Buddy indeed bites into a horse.

Awards

Brian Bolland won the Eisner Award for Best Cover Artist in 1992 for his work on Animal Man.[8] The series also earned several nominations in 1989, for Best Single Issue (#5), Best Writer (Grant Morrison), and Best Series.[9]

Collected editions

Grant Morrison's run on the series has been collected in the following collections:

| Title | Page count | Material collected | Format | Publication date | Publisher | ISBN |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Animal Man, Book 1 - Animal Man | 240 | Animal Man (vol. 1) #1–9 | Paperback | May 1, 2001 | Vertigo | 978-1563890055 |

| Animal Man, Book 2 - Origin of the Species | 224 | Animal Man (vol. 1) #10-17, Secret Origins #39 | Paperback | July 1, 2002 | Vertigo | 978-1563898907 |

| Animal Man, Book 3 - Deus Ex Machina | 232 | Animal Man (vol. 1) #18-26 | Paperback | November 1, 2003 | Vertigo | 978-1563899683 |

| The Animal Man Omnibus | 712 | Animal Man (vol. 1) #1-26, Secret Origins #39 | Hardcover | August 6, 2013 | Vertigo | 978-1401238995 |

Peter Milligan's run on the series has been collected in the following collection:

| Title | Page count | Material collected | Format | Publication date | Publisher | ISBN |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Animal Man Vol. 4: Born to be Wild | 288 | Animal Man (vol. 1) #27-37 | Paperback | February 26, 2013 | Vertigo | 978-1401238018 |

Tom Veitch's run on the series has been collected in the following collection:

| Title | Page count | Material collected | Format | Publication date | Publisher | ISBN |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Animal Man Vol. 5: The Meaning of Flesh | 360 | Animal Man (vol. 1) #38-50 | Paperback | January 28, 2014 | Vertigo | 978-1401242848 |

Jamie Delano's part of the run on the series has been collected in the following collections:

| Title | Page count | Material collected | Format | Publication date | Publisher | ISBN |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Animal Man Vol. 6: Flesh and Blood | 368 | Animal Man (vol. 1) #51-63 | Paperback | July 15, 2014 | Vertigo | 978-1401246792 |

| Animal Man Vol. 7: Red Plague | 408 | Animal Man (vol. 1) #64-79 | Paperback | January 20, 2015 | Vertigo | 9781401251239 |

Jerry Prosser's part of the run on the series will be collected in the following collection:

| Title | Page count | Material collected | Format | Publication date | Publisher | ISBN |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Animal Man Vol. 8 | TBA | Animal Man (vol. 1) #80-89 | Paperback | TBA | Vertigo | TBA |

Jeff Lemire's run on the series is being collected in the following collections:

| Title | Page count | Material collected | Format | Publication date | Publisher | ISBN |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Animal Man Vol. 1: The Hunt | 144 | Animal Man (vol. 2) #1-6 | Paperback | May 8, 2012 | DC Comics | 978-1401235079 |

| Animal Man Vol. 2: Animal vs. Man | 176 | Animal Man (vol. 2) #7-11, #0, Annual #1 | Paperback | January 15, 2013 | DC Comics | 978-1401238001 |

| Animal Man Vol. 3: Rotworld: The Red Kingdom | 232 | Animal Man (vol. 2) #12-19, Swamp Thing #12, 17-18 | Paperback | September 10, 2013 | DC Comics | 978-1401242626 |

| Animal Man Vol. 4: Splinter Species | 144 | Animal Man (vol. 2) #20-23, Annual #2 | Paperback | March 11, 2014 | DC Comics | 978-1401246440 |

| Animal Man Vol. 5: Evolve or Die | 144 | Animal Man (vol. 2) #24-29 | Paperback | November 11, 2014 | DC Comics | 978-1401249946 |

References

- 1 2 3 Irvine, Alex (2008), "Animal Man", in Dougall, Alastair, The Vertigo Encyclopedia, New York: Dorling Kindersley, p. 27, ISBN 0-7566-4122-5, OCLC 213309015

- ↑ Rogers, Vaneta (June 8, 2011). "Lemire Aims for Less Meta, More Family in DCnU ANIMAL MAN". Newsarama. Retrieved September 1, 2011.

- ↑ Renaud, Jeffrey (June 8, 2011). "Lemire Discovers the Dark Sides of "Animal Man" & "Frankenstein"". Comic Book Resources. Retrieved September 1, 2011.

- ↑ Animal Man Vol. 2 Issue #1

- ↑ Animal Man Vol. 2 issue #2-4

- ↑ Animal Man #20

- ↑ Animal Man #21–26

- ↑ 1992 Will Eisner Comic Industry Award Nominees and Winners

- ↑ 1989 Will Eisner Comic Industry Award

External links

- Animal Man at Don Markstein's Toonopedia. Archived from the original on August 31, 2015.

- The Continuity Pages: Animal Man

- First volume of Animal Man at the Grand Comics Database

- Second volume of Animal Man at the Grand Comics Database