Angoulême

| Angoulême | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Angoulême, a view from Hirondelle golf course | ||

| ||

Angoulême | ||

|

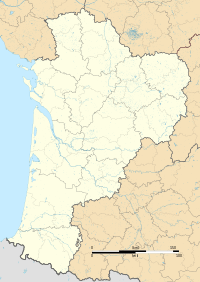

Location within Nouvelle-Aquitaine region  Angoulême | ||

| Coordinates: 45°39′N 0°10′E / 45.65°N 0.16°ECoordinates: 45°39′N 0°10′E / 45.65°N 0.16°E | ||

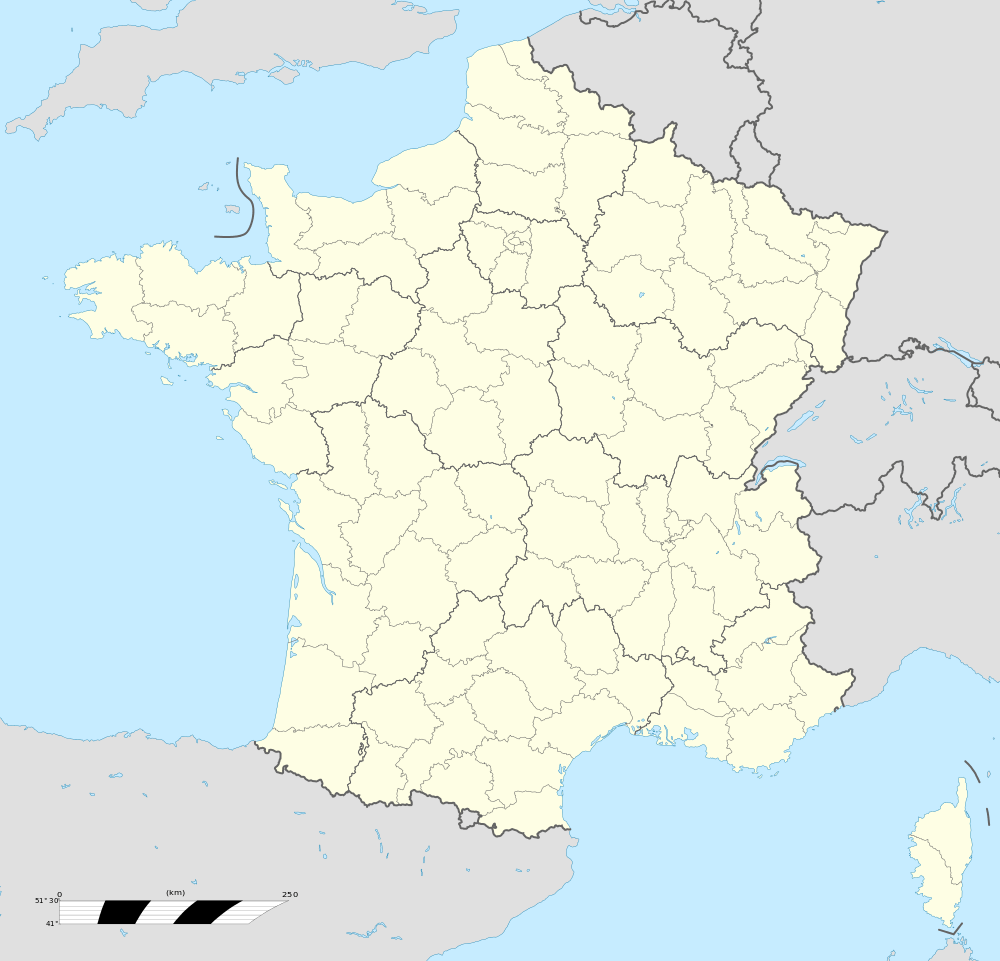

| Country | France | |

| Region | Nouvelle-Aquitaine | |

| Department | Charente | |

| Arrondissement | Angoulême | |

| Canton | Capital of 3 cantons: east, north, and west | |

| Intercommunality | Agglomeration of Grand Angoulême | |

| Government | ||

| • Mayor (2014–2020) | Xavier Bonnefont | |

| Area1 | 21.85 km2 (8.44 sq mi) | |

| Population (2009)2 | 42,242 | |

| • Density | 1,900/km2 (5,000/sq mi) | |

| Demonym(s) |

Angoumoisin (m) Angoumoisine (f) | |

| Time zone | CET (UTC+1) | |

| • Summer (DST) | CEST (UTC+2) | |

| INSEE/Postal code | 16015 / 16000 | |

| Elevation |

27–130 m (89–427 ft) (avg. 100 m or 330 ft) | |

|

1 French Land Register data, which excludes lakes, ponds, glaciers > 1 km² (0.386 sq mi or 247 acres) and river estuaries. 2 Population without double counting: residents of multiple communes (e.g., students and military personnel) only counted once. | ||

Angoulême (French pronunciation: [ɑ̃ɡulɛm]; Occitan: Engoleime (standard) or (locally) Engoulaeme) is a French commune, the capital of the Charente department, in the Nouvelle-Aquitaine region of southwestern France.

The inhabitants of the commune are known as Angoumoisins or Angoumoisines.[1]

Located on a plateau overlooking a meander of the Charente River, the city is nicknamed the "balcony of the southwest". The city proper's population is a little less than 50,000 but it is the centre of an urban area of 110,000 people extending more than fifteen kilometres (9.3 miles) from east to west.[2]

Formerly the capital of Angoumois in the Ancien Régime, Angoulême was a fortified town for a long time and was highly coveted due to its position at the centre of many roads important to communication so therefore suffered many sieges. From its tumultuous past the city, perched on a rocky spur, inherited a large historical, religious, and urban heritage which attracts a lot of tourists.

Nowadays Angoulême is at the centre of an agglomeration which is one of the most industrialised regions between Loire and Garonne (the paper industry was established in the 16th century, a foundry and electromechanical engineering developed more recently). It is also a commercial and administrative city with its own university of technology and a vibrant cultural life. This life is dominated by the famous Angoulême International Comics Festival that contributes substantially to the international renown of the city.

The commune has been awarded four flowers by the National Council of Towns and Villages in Bloom in the Competition of cities and villages in Bloom.[3]

Geography

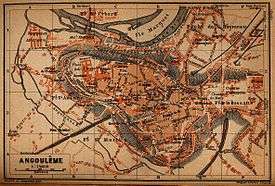

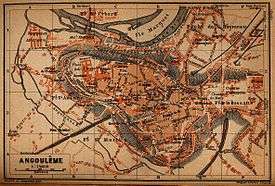

Angoulême is an Acropolis city located on a hill overlooking a loop of the Charente limited in area upstream by the confluence of the Touvre and downstream by the Anguienne and Eaux Claires.

Location and access

Angoulême is located at the intersection of a major north-south axis: the N10 Paris-Bayonne; and the east-west axis: the N14 route Central-Europe Atlantique Limoges-Saintes. Angoulême is also connected to Périgueux and Saint-Jean-d'Angely by the D939 and to Libourne by the D674.

|

La Rochelle 120 km | Paris 435 km Poitiers 110 km Niort 110 km |

Montluçon 236 km Guéret 170 km Confolens 50 km |

|

| Cognac 40 km Saintes 70 km Royan 100 km |

|

Limoges 100 km | ||

| ||||

| | ||||

| Bordeaux 110 km | Libourne 90 km Bergerac 110 km |

Périgueux 80 km |

- By train: the Paris-Bordeaux line, served mainly by TGV, passes through Angoulême and the TER Limoges-Saintes provides connections.

- By water: although the river Charente is currently only used for tourism, it was a communication channel, especially for freight, until the 19th century and the port of l'Houmeau was very busy.

The Angoulême-Cognac International Airport is at Brie-Champniers.

Districts

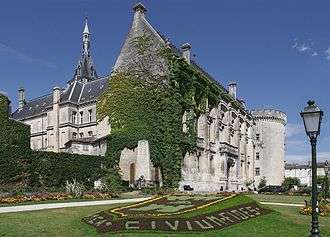

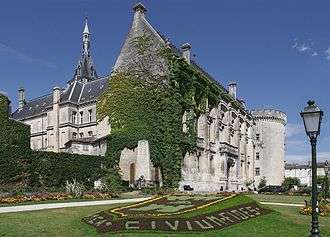

Old Angoulême is the old part between the ramparts and the town centre with winding streets and small squares. The city centre is also located on the plateau and was portrayed by Honoré de Balzac in "The Lost Illusions" as "the height of grandeur and power". There is a Castle, a town hall, a prefecture, and a cathedral with grand houses everywhere. Unlike Old Angoulême, however, the entire city centre was greatly rebuilt in the 19th century.

Surrounding the city were five old faubourgs: l'Houmeau, Saint-Cybard, Saint-Martin, Saint-Ausone, and la Bussatte. The district of l'Houmeau was described by Balzac as "based on trade and money" because this district lived on trade, boatmen, and their scows. The port of l'Houmeau was created in 1280 on the river bank. It marked the beginning of the navigable part from Angoulême to the sea. Saint-Cybard, on the bank of the Charente, was created around the Abbey of Saint-Cybard then became an industrial area with papermills, especially Le Nil. Saint-Martin - Saint-Ausone is a district composed of two former parishes outside the ramparts. At La Bussatte the Champ de Mars esplanade is now converted into a shopping mall, and adjoins Saint-Gelais.

Today the city has fifteen districts:

- Centre-ville

- Old Angoulême

- Saint-Ausone - Saint-Martin

- Saint-Gelais

- La Bussatte - Champ de Mars

- L'Houmeau

- Saint-Cybard

- Victor-Hugo, Saint-Roch is notable for its military presence.

- Basseau is a district which was created in the 19th century with the port of Basseau, the explosives factory in 1821, the Laroche-Joubert papermill in 1842, then the bridge in 1850.

- Sillac - La Grande-Garenne was a private housing estate then was built up with HLM units.

- Bel-Air, la Grand Font in the railway station district with housing blocks from the 1950s at Grand Font.

- La Madeleine which was completely rebuilt after the bombings of 1944.

- Ma Campagne is a district which was detached from Puymoyen commune in 1945[4] and built-up as a collective habitat from 1972.

- Le Petit Fresquet was also detached from Puymoyen and is semi-rural.

- Frégeneuil was also detached from Puymoyen and is semi-rural.

Panorama of the city

The church of Saint-Ausone, the cathedral of Saint-Pierre, and the city hall can all be seen.

Neighbouring communes and villages[5]

|

Saint-Yrieix-sur-Charente | Gond-Pontouvre | L'Isle-d'Espagnac |  |

| Fleac | |

Soyaux | ||

| ||||

| | ||||

| Saint-Michel | Vœuil-et-Giget | Puymoyen |

Hydrography

The Port-l'Houmeau, the old port on the Charente located in the district of l'Houmeau is in a flood zone and during floods the Besson Bey Boulevard is usually cut.

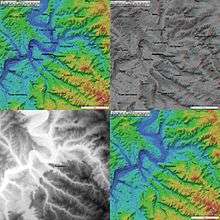

Geology

Geologically the town belongs to the Aquitaine Basin as does three quarters of the western department of Charente.

The commune is located on the same limestone from the Upper Cretaceous period which occupies the southern half of the department of Charente, not far from Jurassic formations beginning at Gond-Pontouvre.

The earliest Cretaceous period - the Cenomanian- is in the relatively low areas (l'Houmeau, the heights of Saint-Cybard, Sillac), at an average altitude of 50m.

The city was established on the Plateau (altitude 100m) that dominates the loop of the River Charente, a Turonian (also called Angoumien) formation which forms a dissected plateau of parallel valleys and a cuesta facing north that extends towards La Couronne to the west and Garat to the east.

This limestone plateau contains natural cavities which have been refurbished by man in the form of three or four floors of caves, some of which include antique grain silos.

The valley of the Charente is made up of old and new alluvium which provides rich soil for farming and some sandpits. These alluvial deposits were deposited successively during the Quaternary period on the inside of two meanders of the river that are Basseau and Saint-Cybard. The oldest alluviums are on the plain of Basseau and reach a relative height of 25m.[6][7][8]

Relief

The old part of the city is built on the plateau - a rocky outcrop created by the valleys of the Anguienne and Charente at an altitude of 102 metres (335 feet) - while on the river bank the area subject to flooding is 27 metres (89 feet) high. Angoulême is characterized by the presence of ramparts on a cliff 80 metres (260 feet) high.

The plateau of Ma Campagne, south of the old town, has almost the same features and peaks at 109 m in the woods of Saint-Martin. The plateau is elongated and separates the valleys of Eaux Claires, which is the southern boundary of the commune, from that of Anguienne, which is parallel.

Both plateaux overlook the Charente valley and the outlying areas such as l'Houmeau, Basseau, and Sillac at their western ends. The plateau of Angoulême is the northwest extension of the Soyaux plateau. L'Houmeau, the station area, and that of Grand-Font are to the north of the plateau along the small Vimière valley, also a tributary of the Charente, but further north (towards Gond-Pontouvre and L'Isle-d'Espagnac) than Anguienne is to the south.

The highest point of the city of Angoulême is at an altitude of 133m near Peusec located to the south-east near the border with Puymoyen. The lowest point is 27 m, located along the Charente at Basseau.[9]

The ramparts

Since Roman times ramparts have surrounded the Plateau of Angoulême. Repeatedly destroyed and rebuilt their reconstruction was finally stopped in the 19th century. The Ramparts are classified as historical monuments![]() [10] and the Ramparts Tour is one of the main attractions of the city.

[10] and the Ramparts Tour is one of the main attractions of the city.

- The Ramparts of Angoulême

-

North Rampart

-

Near the covered market

-

The Léchelle Tower

-

The Rampart du midi

Climate

The climate is oceanic Aquitaine and similar to that of the city of Cognac where the departmental weather station is located.

| Town | Sunshine (hours/yr) |

Rain (mm/yr) | Snow (days/yr) | Storm (days/yr) | Fog (days/yr) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| National Average | 1,973 | 770 | 14 | 22 | 40 |

| Angoulême[12] | 2,027 | 763 | 3 | 23 | 54 |

| Paris | 1,661 | 637 | 12 | 18 | 10 |

| Nice | 2,724 | 767 | 1 | 29 | 1 |

| Strasbourg | 1,693 | 665 | 29 | 29 | 56 |

| Brest | 1,605 | 1,211 | 7 | 12 | 75 |

| Climate data for Cognac | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 9.4 (48.9) |

11.0 (51.8) |

14.4 (57.9) |

16.9 (62.4) |

20.8 (69.4) |

24.3 (75.7) |

26.8 (80.2) |

26.7 (80.1) |

23.5 (74.3) |

19.0 (66.2) |

13.0 (55.4) |

9.8 (49.6) |

18.0 (64.4) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 6.1 (43) |

6.9 (44.4) |

9.7 (49.5) |

11.9 (53.4) |

15.8 (60.4) |

19.0 (66.2) |

21.1 (70) |

20.9 (69.6) |

17.9 (64.2) |

14.4 (57.9) |

9.3 (48.7) |

6.6 (43.9) |

13.3 (55.9) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 2.8 (37) |

2.8 (37) |

4.9 (40.8) |

6.9 (44.4) |

10.6 (51.1) |

13.6 (56.5) |

15.3 (59.5) |

15.0 (59) |

12.3 (54.1) |

9.9 (49.8) |

5.6 (42.1) |

3.3 (37.9) |

8.6 (47.5) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 70.5 (2.776) |

51.4 (2.024) |

57.2 (2.252) |

69.6 (2.74) |

63.8 (2.512) |

50.6 (1.992) |

47.4 (1.866) |

45.3 (1.783) |

59.3 (2.335) |

79.5 (3.13) |

85.1 (3.35) |

83.1 (3.272) |

762.8 (30.031) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1 mm) | 11.6 | 9.2 | 10.1 | 11.2 | 10.5 | 7.4 | 6.9 | 6.5 | 8.0 | 11.2 | 11.5 | 11.6 | 115.7 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 77.3 | 111.1 | 160.2 | 179.3 | 211.4 | 351.4 | 254.6 | 239.4 | 219.3 | 141.6 | 91.4 | 89.6 | 2,026.6 |

| Source: Meteorological data for Cognac - 59m altitude, from 1981 to 2010 January 2015 (French) | |||||||||||||

Toponymy

Since antiquity the name of the town has been attested in many forms:

- Iculisma[13] and Eculisna[14] from the 4th century

- civitas Engolismensium around 400AD[14][15]

- Ecolisima (Merovingian currency)[16]

- Ecolisina and Aquilisima in 511[14]

- Ecolisna in the 6th century[16]

- Egolisma[17]

- Egolisina in the 10th century

- Equalisma, Engolma, Egolesma, and Engolisma[18][19]

- Engolesme at the end of the 12th century.[14]

The absence of any convincing explanation of the origin of the name of the city has led to several attempts to fit etymological explanations unrelated to the well documented old forms and phonetically unlikely:

- It came from incolumissima meaning "very safe and healthy," but there is no trace of an [n] in the most ancient forms and no trace of a [mi] either.

- It was an alteration of in collisnā meaning "on the hill"[20] but a toponym is never formed from the Latin preposition in. As for the French word colline (hill), it was borrowed from the Italian collina at the time of the Renaissance (attested for the first time in 1555).[21] In addition the suffix -isnā was not used to produce derivations from Latin words and it is doubtful that it even exists. Finally, independent alterations of regular phonetic changes occur as a result of analogy or more precisely of popular etymology: that is to say analogy with other similar and frequent used names in the region or an attempt to connect the toponym to a term that makes sense. It is clear that the old forms of Angoulême are mostly obscure.

Some hypotheses have been advanced with a stronger basis:

- It is possible to recognize the suffix -isma in some of the oldest forms which represents an evolution of the Gallic suffix -isama (usually a superlative mark)[16] which is found in the name of the Gallic divinity Belisama and very common in toponymy in toponymic types such as Blesme, Bellême, etc. including changes in the final -esme, -ême which is similar to Angoulême.[Note 1][22] In this context the first element would be Icul- / Ecol- an unknown pre-Latin element.[16]

- The identification of the primitive form Eculisna then alternating the old forms -isna and -isma led Ernest Nègre to prefer the first with -isna. The first element would be Ecul-. According to him, we can neither affirm the Celticity of these two elements nor their meaning. The alteration in *Angulisma was caused by the attraction of the Germanic personal name Angelisma whose existence was confirmed by Marie-Thérèse Morlet.[14]

- Iculisma / Ecolisma would consist of a Gallic radical eco meaning "water", followed by the suffix -lisima meaning "relates to". Iculisma would be "well-watered".[20] Xavier Delamarre analysed the element Eco- to come from Equoranda (or Egoranda) as the origin of many names in France and considers that the element ico / equo- was not Celtic.[22]

At the time of the French Revolution the city was known by the transient name of Montagne-Charente.[20]

- The district of Bussatte takes its name from the Low Latin buxetta / buxettum which means "place planted with boxwood" equivalent to Boissay in the langue d'oïl.

- The district of l'Houmeau meaning "small elm" or "abalone". Actually the term is probably derived from the low Latin ulmellum.

- Sillac probably comes from the low Latin Siliacum meaning that the village was built around the property (suffix -acum) of a Gallo-Roman named Silius.[23]

History

Antiquity

The history of the city is not very well known before the Roman period: it is simply known that the plateau was occupied by an oppidum, traces of which were found during excavations in the Saint-Martial cemetery[24] under the name Iculisma. Its currency was Lemovice.

The town was not located on major roads and was considered by the poet Ausonius as a small town. No Roman monuments have been found but it benefited from the Pax Romana and from trade on the river. The town had a prosperous period at the end of the Roman Empire. The rocky promontory overlooking the Charente 80 metres (260 feet) high and over the Anguienne 60 metres (200 feet) high formed a strategic position. It was raised to the rank of capital of civitas (at the end of the 3rd or 4th centuries) and the first fortress dates from the end of the Roman Empire. The rampart called Bas-Empire which surrounds 27 hectares of land was maintained until the 13th century. The network of Roman roads were then reorganized to link the town with the surrounding cities of Bordeaux, Saintes, Poitiers, Limoges, and Périgueux.[25]

The city of Haut-Empire remained unknown for a long time. Recent excavations have provided details on the power of the Roman city. A well dug in an early era shows that the water table was very high. A large thermal spa complex was found under the courthouse which is usually related to water supply through an aqueduct.[26]

The first bishop of Angoulême was Saint Ausone of Angoulême in the 3rd century. The administrative importance of the city was strengthened by the implementation of a County in the 6th century with Turpion (or Turpin) (839-863), adviser to Charles the Bald. However, the town was always attached to the various kingdoms of Aquitaine and the end of antiquity for the city was in 768, when Pepin the Short defeated Hunald II and linked it to the Frankish kingdom.[27]

Middle Ages

When held by the Visigoths, the city followed the arian version of Christianity and was besieged for the first time by Clovis in 507 after Vouillé then taken in 508;[28] "miraculously" according to Gregory of Tours and Ademar of Chabannes.[29]

During the battle, however, Clovis was seriously wounded in the leg - probably a fracture. The fact is reported by tradition and on a wall of a tower from the 2nd century a leg is carved called the "leg of Clovis".

During his stay in Angoulême, after putting the garrison to the sword, Clovis pulled down the old Visigothic cathedral dedicated to Saint-Saturnin to build a new one bearing the name of Saint-Pierre. All that remains of the original building are two carved marble capitals that frame the bay of the axis in the apse of the present cathedral.

In the 7th century Saint Cybard stayed secluded in a cave beneath the extension to the north wall of Angoulême called Green Garden which caused the creation of the first abbey: the Abbey of Saint-Cybard, then created the first abbey for women: the Abbey of Saint-Ausone where the tomb of the first bishop of the city is located.

In 848 Angoulême was sacked by the Viking chief Hastein.[30] In 896 or 930[31] the city suffered another attack from invading Vikings but this time the Vikings faced an effective resistance. Guillaume I, third Count of Angoulême, at the head of his troops made them surrender in a decisive battle. During this engagement, he split open to the waist Stonius, the Norman chief, with a massive blow together with his helmet and breastplate.

It was this feat that earned him the name Taillefer, which was borne by all his descendants until Isabella of Angoulême who was also known as Isabelle Taillefer, the wife of King John of England. The title was withdrawn from the descendants on more than one occasion by Richard Coeur-de-Lion then the title passed to King John of England at the time of his marriage to Isabella of Angoulême, daughter of Count Aymer of Angoulême. After becoming a widow, Isabella subsequently married Hugh X of Lusignan in 1220, and the title was passed to the Lusignan family, counts of Marche. On the death of Hugh XIII in 1302 without issue, the County of Angoulême passed his possessions to the crown of France.

In 1236 Jewish communities in Anjou and Poitou, particularly Bordeaux and Angoulême were attacked by crusaders. 500 Jews chose conversion and over 3000 were massacred. Pope Gregory IX, who originally had called the crusade, was outraged about this brutality and criticized the clergy for not preventing it.[32]

From the 10th to the 13th centuries the counts of Angoulême, the Taillefer, then the Lusignan strengthened the defences of the city and widened it to encompass the district of Saint-Martial.

In 1110, Bishop Girard II ordered the construction of the present cathedral.

The commune charter

On 18 May 1204 a charter was signed by King John of England to make official the creation of the commune of Angoulême. The King "grants to residents of Angoulême to keep the freedoms and customs of their fair city and defend their possessions and rights". The city celebrated their 800th anniversary throughout 2004.[33]

The Hundred Years War

In 1360 the city, like all of Angoumois, passed into the hands of the Plantagenet English with the Treaty of Brétigny. From 16 to 22 October 1361, John Chandos, Lieutenant of King Edward III of England and the Constable of Aquitaine responsible for implementing the Treaty particularly in Angoumois, took possession of the city, its castles, and the "mostier" (monastery) of Saint-Pierre. He received oaths of allegiance to the King of England from the main personalities of the city.[34]

The English were, however, expelled in 1373 by the troops of Charles V who granted the town numerous privileges. The County of Angoulême was given to Louis d'Orléans who was the brother of King Charles VI in 1394 and it then passed to his son Jean d'Orléans (1400-1467), the grandfather of Marguerite d'Angoulême and François I. The Good Count Jean of Angoulême greatly expanded the County castle after his return from English captivity in the middle of the 15th century.

The modern era

Angoulême, the seat of the County of Angoumois, succeeded to a branch of the family of Valois from which came François I, King of France from 1515 to 1547 who was born in Cognac in 1494. In 1524 the Italian navigator Giovanni da Verrazzano returned from the Indies. He told François I he had discovered a new territory that he named New Angoulême in his honour. This area later became New Amsterdam then New York.

The duchy, now crown land, thereafter was passed on within the ruling house of France. One of its holders was Charles of Valois, the "natural" (or illegitimate) son of Charles IX. The last duke of Angoulême was Louis-Antoine (died 1844), eldest son of Charles X of France.

John Calvin, the promoter of Protestantism and friend of Jean du Tillet the archdeacon of Angoulême, was forced to flee Paris in 1533 and took refuge in Angoulême in the caves of Rochecorail at Trois-Palis. He wrote some of his Institutes of the Christian Religion there which first edition was published in Latin in Basel in 1536.[35]

Angoulême was affected by the Revolt of the Pitauds peasant revolt: in 1541, the gabelle (salt tax) was imposed on Saintonge and Angoumois. These provinces did not pay the tax on salt. The revolt broke out around Angoulême and farmers from the surrounding countryside took the city in July 1548[36]

During the first wars of religion the city took up arms: it was reconquered in 1563 by Montpensier. In 1565 Charles IX passed through the city during his royal tour of France (1564-1566) accompanied by the court.[37] In October 1568 the city was taken by the Protestants under Coligny.[38]

Henry III was, in his infancy, the Duke of Angoulême. He left an unflattering description: "The streets of Engolesme are twisted, houses are disordered, the walls built out of various kinds of masonry which show that it was built several times and often taken and ruined"[39]

In 1588 the mayor of Angoulême, François Normand Lord of Puygrelier, was ordered by Henri III to arrest the Duke of Épernon, governor of Angoumois. He led the assault, was repelled, and died on 10 August 1588.

In 1619 Marie de Médicis escaped and was received by the Duke of Épernon, governor of Angoumois. At that time the castle was the residence of the governors.

French Revolution

During the French Revolution the city was called Mountagne-Charente. The first tree of liberty was planted on 5 July 1792.[40]

World War II

Seen here is a carriage at the Place des Halles before the First World War.

.

On 24 June 1940, the 2nd Verfügungstruppe division (special intervention troops) Das Reich supported by other units of the Wehrmacht arrived in Angoulême. These troops took prisoners and neutralized the many refugee French soldiers in the city. Their number is estimated between 10 and 20 thousand. They were released in the following days.

The Das Reich division, which became tragically famous in 1944 during the Battle of Normandy, continued their "lightning war" by quickly moving to the Spanish border to quickly set the line of demarkation to cut France in two.[41] Angoulême was located in the occupied zone under German authority and was the seat of the Feld Kommandatur. The border with the free zone, colloquially called the zone nono (non-occupied) passed about 20 kilometres (12 miles) east of Angoulême through the Forest of Braconne and split the department in two.

On 20 August 1940 a convoy of Spanish Republicans were sent from Angoulême: convoy 927. This was the first convoy of the history of Deportation in Europe.[42] Men over the age of 13 were sent to the Mauthausen camp where very few survived; women and children were sent to Franco. These refugees were gathered in camps of "Combe aux Loups" at Ruelle-sur-Touvre and "Alliers" in Angoulême. It also served as a concentration camp for Gypsies until June 1946.

On 21 October 1941 the young Gontran Labrégère, who tried with his friend Jean Pierre Rivière to set fire to a train carrying straw and munitions in Angoulême railway station, was shot by the occupiers. This was the first of a long list of 98 resistance fighters or hostages from Charente. In 1942 Mayor Guillon was dismissed and accused of belonging to an organisation outlawed by the Vichy regime. He was replaced by a notable industrialist, Pallas.

On 8 October 1942 387 people of Jewish origin were arrested and deported to Auschwitz. Only eight of them ever returned. On 19 March 1944 allied bombing caused widespread damage and one casualty at the National Explosives factory. On 15 June and 14 August 1944, the railway station was the target of American Flying Fortresses that dumped a carpet of bombs with little damage to the Germans but killing 242 civilians, destroying 400 houses, and caused 5,000 disaster victims in l'Éperon, l'Houmeau, Madeleine, and Grand-Font districts. At the end of August 1944 the Elster column, which was composed of the remains of various German units and the Indische Legion, passed through the city without incident and withdrew.

Various units of FFI from the department and reinforcements from Dordogne then began the encirclement of the city. On the evening of 31 August an attack was launched, putting to flight the remnants of the German garrison. They fortunately did not have an opportunity to reorganize the defence of the city using the numerous and formidable fortifications erected for this purpose. On the night of 31 August to 1 September the city was liberated and a Liberation Committee with a new prefect was installed. This attack, however, resulted in 51 casualties among the different units involved: Maquis de Bir Hacheim, Groupe Soleil, SSS (Special Section for Sabotage), etc.

A museum in the commune is devoted to the Resistance and the deportations of Jewish and political prisoners. A statue near the station commemorates the deportations to the concentration camps. The survivors of Operation Frankton, notable for their daring raid by canoe on the German U-boat base at Bordeaux, made their escape across country to a safe house at Ruffec just north of Angoulême. This is now the site of a shop featuring British goods. The Monument to the Resistance is in Chasseneuil to the east.

Postwar history

After the war, the city underwent a major expansion of its suburbs. First Grand Font and Bel-Air, following the MRU reconstruction program for war damage of the area around the station which was bombed in 1944. Then in the 1960s the districts of Basseau (ZAC) and the Grande-Garenne were built and then there was the creation of Priority Urban Zones (ZUPs) at Ma Campagne in the 1970s.

Gradually industries moved into more spacious industrial zones created in the peripheral communes between 1959 and 1975:[4]

- Sillac-Rabion (1959)

- les Agriers (1964)

- ZI No. 3: Gond-Pontouvre and L'Isle-d'Espagnac (1967)

- Nersac (early 1970s)

- Combe at Saint-Yrieix (1980)

Urbanisation also affected the peripheral communes with housing estates at Soyaux and Ruelle-sur-Touvre and the agglomeration became one of the largest cities in the south-west.[43]

In 1972, the city signed a "pilot city" contract with the State (DATAR, represented by Albin Chalandon),[4][44] which allowed the city to make large scale public works - e.g. the small ring road (bridge and Rue Saint-Antoine, Boulevard Bretagne, Tunnel of Gâtine) penetrating Ma Campagne and called the way to Europe, the ZUPs at Ma Campagne, the Saint-Martial town centre, underground parking at Bouillaud and Saint-Martial, Montauzier indoor swimming pools at Ma Campagne, a pedestrianized street, a one-way traffic plan with computerized management of traffic lights (Angoulême is one of the first cities in France with Bordeaux which has the Gertrude computerized system called Philibert in Angoulême[4]), STGA urban transport (ten routes with flexible buses), development of Bouillaud square, Conservatory of Music.[45]

In 1989 after defeat in the municipal elections, the PS deputy mayor, Jean-Michel Boucheron left a hole of 164 million francs in the finances of the city and a debt of 1.2 billion francs. This deficit has burdened the finances of the city and long served as justification for the non-involvement in the completion of public works.

The small ring road (the southwest quarter - i.e. the Aquitaine Boulevard, a second bridge over the Charente, and the connection to the way of Europe) was completed in 1995.

Following the construction of the Nautilis swimming complex at Saint-Yrieix by the urban community, the town of Angoulême closed three swimming pools in 2001 (Montauzier, Ma Campagne and the Bourgines summer pool).[46]

Heraldry

.svg.png) |

Accompanying the devise: "FORTITUDO MEA CIVIUM FIDES" meaning "My strength is in the loyalty of my citizens" (The same device as Périgueux).

Blazon: |

- Development of the coat of arms

- The first known blazon was: Azure Semé-de-lis of Or, a city gate with two towers of argent debruised by the whole.

- Under Philip V in 1317: The Two Towers became three.

- Under Charles VI in 1381 are: Azure Semé-de-lis of Or, a bend compony of Argent and Or debruised by the whole for brisure. The door at tower three encloses an outdoor ornament.

- Under Charles VII in 1452 the brisure changes for: a label of three points, with the middle pointed.

- In the 16th century, the door with two towers reappears surmounted by a fleur de lys of gold.

- In 1850 a star replaced the fleur de lys which reappeared in 1855.

- At an unknown date the crown was added.

Administration

Municipality

| From | To | Name | Party | Position |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1212 | Barthélémy du Puy | |||

| 1215 | Pierre Guillaume | |||

| 1218 | Hélie d'Aurifont | |||

| 1381 | 1382 | Jehan Teinturier | ||

| 1390 | 1392 | Jehan Prevost | ||

| 1393 | Brugier | |||

| 1396 | 1399 | Bernard de Jambes | ||

| 1397 | Cumon | |||

| 1399 | Mangot Prevost | |||

| 1400 | Jehan Prevost | |||

| 1402 | Hélie Martin | |||

| 1410 | Gentil | |||

| 1415 | Baron | |||

| 1420 | Pelletan | |||

| 1429 | de Lage | |||

| 1431 | Seguin | |||

| 1435 | Fourreau | |||

| 1437 | Jehan Musnier | |||

| 1438 | Arnauld Mat | |||

| 1439 | de Lisee | |||

| 1443 | 1444 | Pierre Dormois | ||

| 1445 | 1446 | Arnauld Mat | ||

| 1446 | 1447 | Jehan Pelletan | ||

| 1453 | Faure | |||

| 1457 | Héliot Martin | |||

| 1458 | Jehan du Mayne | |||

| 1460 | Pierre du Sou | |||

| 1461 | Guillaume Prevost | |||

| 1462 | Perrinet de la Combe | |||

| 1463 | Jehan Maqueau | |||

| 1464 | Penot de la Combe | |||

| 1465 | Perrinet de la Combe | |||

| 1466 | Penot Seguin | |||

| 1467 | Penot de la Combe | |||

| 1468 | Hélie Martin | |||

| 1469 | Perrinet de la Combe | |||

| 1470 | Penot de la Combe | |||

| 1471 | Guillaume Prevost | |||

| 1472 | Penot Seguin | |||

| 1473 | Perrinet du Sou | |||

| 1474 | Penot de la Combe | |||

| 1475 | Perrinet de la Combe | |||

| 1476 | Jehan du Mayne | |||

| 1477 | Pierre du Sou | |||

| 1478 | Penot de la Combe | |||

| 1479 | Jacques Bareau | |||

| 1480 | 1481 | Philippe de la Combe | ||

| 1482 | Penot de la Combe | |||

| 1482 | 1483 | Michel Montgeon | ||

| 1483 | Jacques Bareau | |||

| 1484 | 1485 | Guillaume Brugier | ||

| 1486 | 1487 | Jacques Bareau | ||

| 1488 | Philippe de la Combe | |||

| 1489 | Jehan Fourreau | |||

| 1490 | Hélie Debresme | |||

| 1491 | Bernard Seguyn | |||

| 1491 | 1492 | Jehan du Mayne | ||

| 1492 | Jehan de Lousmelet | |||

| 1493 | 1494 | André de Bar | ||

| 1495 | 1498 | Hélie Seguin | ||

| 1498 | 1499 | Penot du Mayne | ||

| 1499 | 1500 | Georges Cimitiere | ||

| 1500 | Anthoyne Gentilz | |||

| 1501 | Regnault Caluau | |||

| 1502 | 1503 | Hélie du Tillet | ||

| 1504 | Hélie de Lagear | |||

| 1505 | Cibard Couillard | |||

| 1506 | 1507 | Pierre de La Place | ||

| 1509 | 1510 | Guillaume Caluau | ||

| 1511 | Cibard Couillard | |||

| 1512 | Pierre de La Combe | |||

| 1513 | Charles Odeau | |||

| 1514 | 1515 | Charles de Lousmellet | ||

| 1516 | Etienne Rousseau | |||

| 1517 | 1518 | Caluau | ||

| 1519 | Pierre Boessot | |||

| 1520 | 1522 | Bernard de Marcilhac | ||

| 1523 | Jehan de Paris | |||

| 1524 | Laurent Journault | |||

| 1528 | Jacques de Lesmerie | |||

| 1529 | Martial Lizee | |||

| 1530 | Guillaume Caluau | |||

| 1533 | Pierre Pascauld | |||

| 1534 | Guillaume Ruspide | |||

| 1535 | Loys Estivalle | |||

| 1536 | Jean Montgeon | |||

| 1537 | Georges Ruspide | |||

| 1538 | François Rouhault | |||

| 1539 | Simon Moreau | |||

| 1540 | François de Couillault | |||

| 1541 | Ythier Jullien | |||

| 1543 | Jean Blanchard | |||

| 1544 | Jean de Paris | |||

| 1545 | Guillaume Ruffier | |||

| 1546 | Jean Blanchard | |||

| 1547 | Aymar Le Coq | |||

| 1548 | Poirier | |||

| 1549 | Simon Moreau | |||

| 1550 | Guillaume de La Combe | |||

| 1551 | 1552 | François de Couillard | ||

| 1553 | François Terrasson | |||

| 1554 | 1555 | Guillaume Rousseau | ||

| 1556 | 1557 | Jean Desmoulins | ||

| 1558 | Jean Ruffier | |||

| 1559 | 1560 | Hélie Dexmier | ||

| 1561 | Hélie de La Place | |||

| 1562 | Jean Paulte | |||

| 1563 | Hélie Baiol | |||

| 1563 | François de La Combe | |||

| 1564 | Michel Constantin | |||

| 1565 | François de La Combe | |||

| 1566 | Michel Constantin | |||

| 1567 | François de La Combe | |||

| 1568 | Jean Girard | |||

| 1569 | Etienne Pontenier | |||

| 1570 | Jean Paulte | |||

| 1571 | Nicolas Ythier | |||

| 1572 | François de Voyon | |||

| 1573 | Mathurin Martin | |||

| 1574 | 1577 | Jean Pommaret | ||

| 1578 | François Redond | |||

| 1579 | Pierre Gandillaud | |||

| 1580 | Pierre Terrasson | |||

| 1581 | 1582 | Pierre Bouton | ||

| 1583 | Louis de Lesmerie | |||

| 1585 | Hélie Laisne | |||

| 1586 | Denys Chappiteau | |||

| 1587 | Guymarc Bourgoing | |||

| 1588 | François Normand de Puygrelier | |||

| 1589 | Etienne Villoutreys | |||

| 1590 | Hélie Laisne | |||

| 1591 | Jacques Lemercier | |||

| 1592 | 1593 | François Le Meusnier | ||

| 1594 | Cybard Laisne | |||

| 1595 | Jean Nesmond | |||

| 1596 | Pierre Terrasson | |||

| 1597 | Jean Pommaret | |||

| 1598 | 1599 | Jacques Le Mercier | ||

| 1600 | François Le Meusnier | |||

| 1601 | Antoine Moreau | |||

| 1602 | Jean du Fosse | |||

| 1603 | Jacques de Villoutreys | |||

| 1604 | Jean de Paris | |||

| 1605 | Charles Raoul | |||

| 1606 | François Desruaux | |||

| 1607 | 1608 | François Ruffier | ||

| 1609 | 1610 | Jacques Le Meusnier | ||

| 1611 | Jean Nesmond | |||

| 1612 | Guillaume Guez de Balzac | |||

| 1613 | François Desruaux | |||

| 1614 | 1616 | Jacques Le Meusnier | ||

| 1617 | 1619 | Jean Guerin | ||

| 1620 | Jean de Paris | |||

| 1621 | François Desruaux | |||

| 1622 | Jacques Le Meusnier | |||

| 1623 | Antoine Gandillaud | |||

| 1624 | Pierre Desforges | |||

| 1625 | 1626 | Guillaume Lambert | ||

| 1627 | François Dufosse | |||

| 1628 | Pierre Bareau | |||

| 1629 | Jean de Paris | |||

| 1630 | Jean Guerin | |||

| 1631 | Abraham Jameu | |||

| 1632 | 1633 | Paul Thomas | ||

| 1634 | 1635 | Jean Souchet | ||

| 1636 | 1637 | Hélie Levequot | ||

| 1638 | Hélie Houlier | |||

| 1639 | 1640 | Philippe Arnold | ||

| 1641 | 1642 | Jean Boisson | ||

| 1643 | 1644 | Antoine Racault | ||

| 1645 | 1646 | François Normand de Puygrelier | ||

| 1647 | François Pommet | |||

| 1648 | 1649 | Jean Lambert | ||

| 1650 | 1651 | Jean Guymard | ||

| 1652 | Pierre Briant | |||

| 1653 | 1654 | François Normand de Puygrelier | ||

| 1655 | Philippe Arnaud | |||

| 1656 | Jean Preverauld | |||

| 1657 | 1658 | Jean Gilibert | ||

| 1659 | Samuel Paquet | |||

| 1660 | Abraham de La Farge | |||

| 1662 | Jean du Thiers | |||

| 1664 | 1666 | Jean de l'Etoile | ||

| 1667 | 1669 | Jacques Morin | ||

| 1670 | François Castin | |||

| 1673 | François Abraham de Guips | |||

| 1676 | Louis de Chazeau | |||

| 1679 | François Nadaud | |||

| 1682 | 1683 | Jean Arnauld | ||

| 1686 | Jean Cadiot de Pontenier | |||

| 1689 | Jean Louis Guitton | |||

| 1692 | Jean Fe | |||

| 1693 | Etienne Cherade | |||

| 1708 | Mesnard de Laumont | |||

| 1718 | Jean Gervais | |||

| 1721 | Pierre Arnauld | |||

| 1723 | Henri Rambaud | |||

| 1724 | François Arnauld | |||

| 1728 | Jean Mesnard | |||

| 1731 | Louis Cosson | |||

| 1738 | Jean Valteau | |||

| 1741 | Elie-Philippe Maulde | |||

| 1744 | Pierre de Sarlande | |||

| 1747 | Léonard du Tillet | |||

| 1754 | Pierre de Labatud | |||

| 1757 | Claude Tremeau | |||

| 1760 | Noël Limousin | |||

| 1765 | Dassier | |||

| 1766 | Dumas | |||

| 1768 | François Bourdage | |||

| 1771 | Chaigneau de La Graviere | |||

| 1773 | Pierre Marchais de La Berge | |||

| 1790 | Jean Valleteau de Chabrefy | |||

| 1790 | Perier de Gurat |

(Not all data is known)

| From | To | Name | Party | Position |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1791 | Louis Desbrandes | |||

| 1792 | André Resnier | |||

| 1793 | Henry | |||

| 1793 | Michel Marvaud-Baudet | |||

| 1793 | Louis Desbrandes | |||

| 1794 | Michel Marvaud-Baudet | |||

| 1795 | Louis Desbrandes | |||

| 1795 | Louis Joseph Trion Montalembert | |||

| 1795 | Abraham François Robin Puynege | |||

| 1795 | Michel Marvaud-Baudet | |||

| 1796 | Jean Auguste Dervaud | |||

| 1797 | Pierre Mallet | |||

| 1797 | François Blandeau | |||

| 1800 | Etienne Souchet | |||

| 1804 | Descravayat de Belat | |||

| 1813 | Pierre Lambert des Andreaux | |||

| 1815 | Jean-Baptiste Marchadier | |||

| 1816 | Pierre Lambert des Andreaux | |||

| 1816 | Pierre Jean Thevet | |||

| 1825 | Eutrope Alexis de Chasteignier | |||

| 1830 | Ganivet | |||

| 1830 | Laurent Sazerac de Forge | |||

| 1830 | Philippe Pierre de Lambert | |||

| 1833 | Henri Bellamy | |||

| 1835 | Alexis Gellibert | |||

| 1837 | Paul Joseph Normand de La Tranchade | |||

| 1841 | Pierre Vallier | |||

| 1843 | Zadig Rivaud | |||

| 1848 | Antony Cheneuzac | |||

| 1849 | Paul Joseph Normand de La Tranchade | |||

| 1855 | Edmond Thomas | |||

| 1855 | François Léon Bourrut-Duvivier | |||

| 1864 | Laurent Paul Sazerac de Forge | |||

| 1870 | Jean Marrot | |||

| 1874 | Pierre Eugène Decescaud | |||

| 1875 | Jean Hippolyte Broquisse | |||

| 1879 | Jean Marrot | |||

| 1881 | Henri Bellamy | |||

| 1888 | Jean Marrot | |||

| 1894 | Auguste Mullac | |||

| 1896 | Jean Donzole | |||

| 1900 | Auguste Mulac | |||

| 1919 | Jean Texier | |||

| 1925 | Gustave Guillon | |||

| 1941 | 1944 | Ariste Pallas |

(Not all data is known)

List of Successive Mayors since 1944[47]

| From | To | Name | Party | Position |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1944 | 1945 | Antoine Rougerie | ||

| 1945 | 1947 | Antonin Denis | ||

| 1947 | 1955 | Roger Baudrin | ||

| 1955 | 1958 | Henri Thébault | CNI | MP for Charente |

| 1958 | 1959 | Raoul Boucheron | ||

| 1959 | 1970 | Henri Thébault | CNI | |

| 1970 | 1977 | Roland Chiron | CNI | Lawyer |

| 1977 | 1989 | Jean-Michel Boucheron | PS | Professor, MP |

| 1989 | 1997 | Georges Chavanes | UDF | Industrialist, MP, Minister |

| 1997 | 2008 | Philippe Mottet | UMP | University Professor, Regional Councillor |

| 2008 | 2014 | Philippe Lavaud | PS | Professor |

| 2014 | 2020 | Xavier Bonnefont | UMP |

(Not all data is known)

Cantons

Angoulême is divided into three cantons:

- Angoulême East Canton has 13,103 inhabitants

- Angoulême North Canton has 14,103 inhabitants

- Angoulême West Canton has 15,906 inhabitants

Intercommunality

The Urban Community of Greater Angoulême or Grand Angoulême includes 16 communes: Angoulême, Fleac, Gond-Pontouvre, La Couronne, Linars, L'Isle-d'Espagnac, Magnac-sur-Touvre, Mornac, Nersac, Puymoyen, Ruelle-sur-Touvre, Saint-Michel, Saint-Saturnin, Saint-Yrieix-sur-Charente, Soyaux, and Touvre.

The population of the conurbation was 103,501 inhabitants in 2006[2] (102,368 in 1999[48]).

Budget and taxation

Taxation is at a rate of 40.20% on buildings, 71.94% on undeveloped land, and 18.43% for the housing tax (2007 figures).

The urban community levies 19.20% business tax.

Urbanism

The Champ de Mars is the central square of the city and has had an underground shopping arcade since September 2007.

The eastern ring road was opened in 2004 (2010 for the final section) which opened up several districts. The deviation of the N10 which has bypassed the city since 1973[49] has formed a western ring road since 2004 when the initial Fléac-Linars project was abandoned.

Rehabilitation operations for collective housing are underway as part of the government Operation for Urban Renewal. The districts of Grande Garenne, Basseau and Ma Campagne were combined in a program of urban regeneration.

-

The historic centre with the city hall and the market

-

Pedestrian Mall in the centre

-

The port of l'Houmeau and, in the background, the town centre of Angoulême.

-

District of Grande-Garenne

-

District of Grand-Font

-

Les Halles

-

The Bardines Hotel

Movies and TV series shot in Angoulême

- Blanche and Marie by Jacques Renard with Miou-Miou and Sandrine Bonnaire, shot in Angoulême and Rouillac, released in 1985

- The Child of the Dawn with Thierry Lhermitte filmed at Angoulême and Cognac

- SOS 18 shot in and around Angoulême

- Father and Mayor filmed in the communes of Angoulême and Magnac-sur-Touvre (in the series, Angoulême is called Ville-Grand)

- My son anyway by Williams Crépin with Clémentine Célarié in 2004.

- And you About Love? by Lola Doillon, 2007

- Mammuth by Benoit Delépine and Gustave Kervern

- To the four winds by Jacques Doillon

- Dying of love by Josée Dayan, with Muriel Robin

- At the bottom of the ladder by Arnaud Mercadier with Vincent Elbaz, Claude Brasseur, Bernadette Lafont, and Helena Noguerra

- Victoire Bonnot with Valerie Damidot and Shirley Bousquet filmed at the Saint-Paul Secondary School

- The Lies by Fabrice Cazeneuve with Hippolyte Girardot and Marilyne Canto, filmed in Angoulême and Puymoyen, released in 2010

- Code Lyoko Evolution, filmed mid-2012 at the Lycée Guez de Balzac

- Le Grand Soir filmed at Angoulême and the ZAC at Montagnes by Benoit Delépine and Gustave Kervern with Albert Dupontel and Benoît Poelvoorde 2012.

- Indiscretions by Josée Dayan with Muriel Robin, filmed during the summer of 2013 in Angoulême, Saint-Même-les-Carrières and Bassac, released in November 2013.

Twin towns – sister cities

Angoulême is twinned with ten other cities around the world:[50]

|

|

Demography

Demographic classification

| Zones | Population | Area (km2) | Density (/km2) | change 1999-2007 |

| Urban Area of Angoulême | ||||

| Angoulême | 42,669 | 22 | 1,940 | - 1.16% |

| Urban Unit | 109,009 | 202 | 540 | + 2.39% |

| Urban Area | 161,282 | 1234 | 131 | + 4.90% |

| Demography of Charente | ||||

| Charente | 349,535 | 5,956 | 59 | + 2.9% |

By population the city of Angoulême is by far the largest city in Charente with 42,242 inhabitants on 1 January 2009.

With a communal area of 2,185 hectares, the density of population is 1,940 inhabitants per km2, making it the most densely populated city in Charente and the third most densely populated city in Nouvelle-Aquitaine after La Rochelle and Poitiers.

In 2008, the Urban Unit of Angoulême, which includes eighteen communes[Note 2] totaled 109,553 inhabitants[51] and its Urban Area, which includes 80 suburban communes in the impact zone of the city, totaled 174,482 inhabitants.[52]

It brings together nearly 106,000 inhabitants within an urban conurbation which extends over fifteen kilometres (9.3 miles) from north to south.[2] Angoulême is the most populous commune in the department of Charente and is the third largest Urban Unit in Nouvelle-Aquitaine, ranking just after Poitiers and La Rochelle and ahead of Niort.

Its Urban Area has 178,650 inhabitants and is composed of 108 communes.[53]

The different data show that Angoulême is the largest urban agglomeration in Charente.

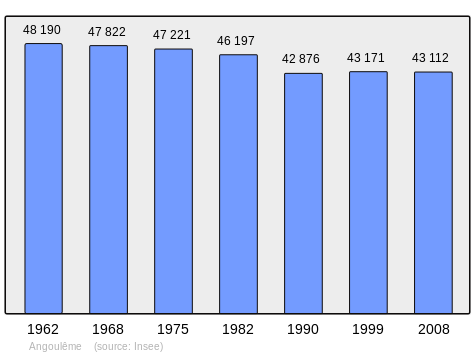

Demographic changes

In 2009 Angoulême had 42,242 inhabitants (down 2% compared to 1999). The commune was 160th in size at the national level, while it was at 145th in 1999, and 1st at the departmental level out of 404 communes.

Demography

The evolution of the number of inhabitants is known through the population censuses conducted in the commune since 1793. From the 21st century, a census of communes with fewer than 10,000 inhabitants is held every five years, unlike larger towns that have a sample survey every year.[Note 3]

| 1793 | 1800 | 1806 | 1821 | 1831 | 1836 | 1841 | 1846 | 1851 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 11,500 | 13,000 | 15,011 | 15,025 | 15,186 | - | 18,622 | 20,085 | 21,155 |

| 1856 | 1861 | 1866 | 1872 | 1876 | 1881 | 1886 | 1891 | 1896 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 22,811 | 24,961 | 25,116 | 25,928 | 30,513 | 32,567 | 34,647 | 36,690 | 38,068 |

| 1901 | 1906 | 1911 | 1921 | 1926 | 1931 | 1936 | 1946 | 1954 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 37,650 | 37,507 | 38,211 | 34,895 | 35,994 | 36,699 | 38,915 | 44,244 | 43,170 |

| 1962 | 1968 | 1975 | 1982 | 1990 | 1999 | 2006 | 2009 | - |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 48,190 | 47,822 | 47,221 | 46,197 | 42,876 | 43,171 | 41,500 | 42,242 | - |

Sources : Ldh/EHESS/Cassini until 1962, INSEE database from 1968 (population without double counting and municipal population from 2006)

Distribution of age groups

Percentage Distribution of Age Groups in Angoulême and Charente Department in 2009

| Angoulême | Angoulême | Charente | Charente | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age Range | Men | Women | Men | Women |

| 0 to 14 Years | 17.1 | 15.1 | 17.3 | 15.5 |

| 15 to 29 Years | 25.6 | 20.7 | 16.4 | 14.4 |

| 30 to 44 Years | 20.8 | 18.6 | 19.2 | 18.5 |

| 45 to 59 Years | 17.5 | 18.5 | 22.2 | 21.5 |

| 60 to 74 Years | 11.6 | 13.8 | 15.8 | 16.2 |

| 75 to 89 Years | 7.0 | 12.0 | 8.6 | 12.3 |

| 90 Years+ | 0.4 | 1.3 | 0.5 | 1.6 |

Sources:

- Evolution and Structure of the population of the Commune in 2009, INSEE.

- Evolution and Structure of the population of the Department in 2009, INSEE.

Economy

Angoulême is a centre of the paper-making and printing industry, with which the town has been connected since the 14th century. Papermaking is favoured because of the uniform temperature and volume of the water year-round, partly due to the Touvre River, which joins the Charente at Angoulême. The Touvre is the second largest river with an underground source in France after the River Sorgue (Fontaine-de-Vaucluse).

The Touvre emerges as a full-blown river from the head of the valley at Ruelle. A trout fishery is located at the source and a pumping station supplies the drinking water needs of Angoulême. Most of the paper mills are situated on the banks of watercourses in the neighbourhood of the town. Cardboard for packaging, as well as fine vellum for correspondence, have been produced in quantity.

The best known export is Rizla+ cigarette roll-up paper, a combination of riz (rice paper) and LaCroix, after Monsieur LaCroix the founder. Le Nil is another local brand of roll-up paper, named not after the Nile in Egypt but after a small tributary of the Charente. The Le Nil paper-mill is now the Paper Museum.[54] Paper-making in the town has been in decline.

The economy of the modern town also is supplemented by annual tourist events and festivals. For example, the printers and paper-makers, whose industry relied on intricate machinery, became skilled mechanics and among the first to become fascinated with the motor car in the late 19th century. Motor trials were held regularly, starting on the long straight road through Puymoyen, now a suburb. Monsieur LaCroix (of RIZLA+) was a celebrated motorcycle racer. The Paris-Madrid road race of 1903, notorious for its cancellation due to numerous deaths, passed through Angoulême. Marcel, one of the brothers Renault, was one of the victims. The place of his death is marked by a memorial on road RN10 to Poitiers.

The town has been closely associated with motor trials and racing. The Circuit des Remparts (see below) is held annually, one of the last such street-racing course in France, together with Pau (and Monaco). In addition to local heroes, internationally known racing drivers, such as Juan Manuel Fangio, José Froilán González, Jean-Pierre Wimille, Pierre Veyron and Maurice Trintignant, have been regular participants. The famous cars which they drove frequently are presented at the modern event. The hotel and restaurant trade receives a considerable boost from the races.

Subsidiary industries, such as the manufacture of machinery, electric motors and wire fabric, are of considerable importance. Angoulême is the most inland navigable port on the Charente River. The traditional river boat is the Gabare. Iron and copper founding, brewing and tanning also continue. The manufacture of gunpowder, confectionery, heavy iron goods, gloves, boots and shoes (including the traditional pantoufle carpet slippers) and cotton goods are also important. There is wholesale and retail trade in wine, cognac and building-stone.

Transportation

The Gare d'Angoulême railway station offers connections to Paris, Bordeaux, Tours, Limoges and several regional destinations. The main line of the Paris Bordeaux railway passes through a tunnel beneath the town and is due for large-scale refurbishment to improve travel time. The new high-speed link between Tours and Bordeaux has been approved and will bypass the town centre to the west, but with a link to Angoulême station from both the north and south. It is due to open in 2017.

Angoulême - Brie - Champniers Airport, newly named Angoulême-Cognac airport, is situated 9.5 km (5.9 mi) NE of the city centre in Champniers, just off the N10. The runway can accommodate the Boeing 737, and a new restaurant and shops were added in 2008.[55] However Ryanair stopped its Angoulême-Stansted service in 2010. Air France used to operate a service to Lyon. There are currently no regular flights to/from Angoulême airport.

Local Buses – The city bus system is run by STGA.

Culture and heritage

Angoulême and Angoumois country together are classified as a City of Art and History.

In place of its ancient fortifications, Angoulême is encircled by boulevards above the old city walls, known as the Remparts, from which fine views may be obtained in all directions. Within the town the streets are often narrow. Apart from the cathedral and the City Hall, the architecture is of little interest to purists. However, the "old town" has been preserved, maintained and largely reserved for pedestrians. It has a cobbled restaurant quarter, with several galleries and boutiques.

Angoulême contains a very large number of buildings and structures which are registered as historical monuments. For a complete list including links to descriptions (in French) click here.

Below are listed some of the most interesting sites.

Civil heritage

- The Town Hall (13th century)

[56] was designed by Paul Abadie and is a handsome 19th-century structure. It has preserved and incorporated two 13th-century towers, Lusignan and Valois, from the Castle of the Counts of Angoulême on the site on which it was built. It contains museums of paintings and archaeology.[57]

[56] was designed by Paul Abadie and is a handsome 19th-century structure. It has preserved and incorporated two 13th-century towers, Lusignan and Valois, from the Castle of the Counts of Angoulême on the site on which it was built. It contains museums of paintings and archaeology.[57] - The Ramparts (4th century).

[10][58][58] The ramparts form a balcony overlooking the Charente.

[10][58][58] The ramparts form a balcony overlooking the Charente. - The Market building (1886)

[59] is made of architectural glass and iron of Baltard type.

[59] is made of architectural glass and iron of Baltard type. - The Palace of Justice was built on an old convent at the end of the 19th century by Paul Abadie's father.

- The Municipal Theatre has a superb façade.

- The College Jules Verne, a former deanery, it has preserved the old chapel with beautiful stained glass and carved woodwork in the music room and a vaulted chapel with stone keystones and stained glass - visible from the Rue de Beaulieu - which has become the CDI.

- The Guez de Balzac School built by Paul Abadie father and son.

There are very many old houses:

- The Maison Saint-Simon in Rue de la Cloche-Verte (16th century)

[60] built in the Renaissance style.[61]

[60] built in the Renaissance style.[61] - The Hotel de Bardines at 79 Rue de Beaulieu (18th century)

[62] is attributed to the Angoulême architect Jean-Baptiste Michel Vallin de la Mothe. The building is impressive in size.[63]

[62] is attributed to the Angoulême architect Jean-Baptiste Michel Vallin de la Mothe. The building is impressive in size.[63] - The Hotel Montalembert[64]

- The House called Archers[65]

- The Hôtel Mousnier-Longpré at 24 Rue Friedland (12th century)

[66] was rebuilt in the 15th century. It has remarkable façades on the Rue de l’Évêché, Rue de Friedland, and the courtyard.

[66] was rebuilt in the 15th century. It has remarkable façades on the Rue de l’Évêché, Rue de Friedland, and the courtyard. - A Hotel Particular described in Illusions perdues (Lost Illusions) by Honoré de Balzac as that of Madame de Bargeton.

- An Ancient Portal at 59 Rue du Minage (17th century)

[67]

[67] - An Ancient Portal at 61 Rue du Minage (16th century)

[68]

[68]

- Places (Squares) in Old Angoulême[69]

- The Place du Minage with its fountain from the Second Empire and its benches has a Mediterranean flair in the heart of the old town. In the 14th and the 19th centuries there was intense commercial activity.

- The Place Henri Dunant. Named after the founder of the Red Cross, it now borders the Gabriel Fauré conservatory, formerly the Saint-Louis College then a Police Station.

- The Place New-York. This square, formerly called the Park, was installed in the 18th century in the first real town planning project. It has remained a promenade and a venue for various events. In 1956 the square changed its name again. The City Council decided to call it the Place New York, in memory of the journey by Giovanni da Verrazano in the service of François I who, in 1524, named the site of the present New York: New Angoulême.

- The 'Place Beaulieu. Located at the western end of the plateau and the old city, it offers a vast panorama to passers-by and has long been a pleasant place to walk. It borders the imposing Guez de Balzac School on the site of an ancient abbey.

- The Place Bouillaud and the Place de l'Hotel de Ville. In addition to the City Hall there is also (in front of the entrance to the City Hall) a beautiful art nouveau façade.

- The Place Francis Louvel. Formerly called du mûrier, it was and remains one of the busiest places in the old town. Formerly the garden of a convent until the 16th century, it was embellished in the 18th and 19th centuries with new buildings and a fountain. The Palace of Justice is there. The place changed its name in 1946 to take the name of Francis Louvel - a resistance fighter shot by the Germans in 1944.

- The Place du Palet. This site occupies a vast space which, in the past, was in front of the main gate of the old city and for three centuries housed an imposing hall. The site was redeveloped in the 1980s.

- The Place du Général Resnier.

Tours of the town include the murs peints, various walls painted in street-art cartoon style, a feature of Angoulême and related to its association with the bande dessinée, the comic strip. A statue has been erected to Hergé, creator of The Adventures of Tintin. The attractive covered market Les Halles, on the site of the old jail, was restored and refurbished in 2004 and is a central part of city life.

In 2009 the National Council of Cities and Villages in Bloom of France[70] awarded four flowers to the commune in the competition for cities and villages in bloom.

- Gallery

-

Watchtower in the old Épernon wall -

City Hall -

The Pedestrian Mall in 1992 -

The 19th-century gate on the Hotel Montalembert -

The Palace of Justice -

The Municipal Theatre -

Entrance to the Guez de Balzac school

Religious heritage

- Angoulême Cathedral (12th century)

[71] is dedicated to Saint Peter and is a church in the Romanesque style. It has undergone frequent restoration since the 12th century. It was partly rebuilt in the latter half of the 19th century by architect Paul Abadie. The façade, flanked by two towers with cupolas, is decorated with arcades featuring statuary and sculpture with the whole representing the "Last Judgment". The crossing is surmounted by a dome. The north transept is topped by a fine square tower over 160 ft (49 m) high. The Cathedral contains a very large number of items that are registered as historical objects. For a complete list including links to descriptions (in French) click here.

[71] is dedicated to Saint Peter and is a church in the Romanesque style. It has undergone frequent restoration since the 12th century. It was partly rebuilt in the latter half of the 19th century by architect Paul Abadie. The façade, flanked by two towers with cupolas, is decorated with arcades featuring statuary and sculpture with the whole representing the "Last Judgment". The crossing is surmounted by a dome. The north transept is topped by a fine square tower over 160 ft (49 m) high. The Cathedral contains a very large number of items that are registered as historical objects. For a complete list including links to descriptions (in French) click here. - The remains of the Abbey of Saint-Cybard (13th century)

[72] at the International City of Cartoons and Images (CNBDI)

[72] at the International City of Cartoons and Images (CNBDI) - The Church of Saint-André at Rue Taillefer (12th century)

[73] has been rebuilt several times. The church contains a large number of items that are registered as historical objects. For a complete list with links to descriptions (in French) click here.

[73] has been rebuilt several times. The church contains a large number of items that are registered as historical objects. For a complete list with links to descriptions (in French) click here. - A Lantern of the Dead in the cemetery of the Church of Saint André (12th century)

[74] is actually a hearth - a remnant of the old Taillefer Palace.

[74] is actually a hearth - a remnant of the old Taillefer Palace. - The old Bishop's Palace at Rue Friedland (15th century)

[75] is today the Museum of Fine Arts of Angoulême. The bishop's house contains a number of items that are registered as historical objects:

[75] is today the Museum of Fine Arts of Angoulême. The bishop's house contains a number of items that are registered as historical objects:

- The Hospital Chapel

[81] was the old Chapel of the Cordeliers Convent where Guez de Balzac is buried. The chapel contains several items that are registered as historical objects:

[81] was the old Chapel of the Cordeliers Convent where Guez de Balzac is buried. The chapel contains several items that are registered as historical objects:

- A Tapestry: Pagan Sacrifice to an Idol (18th century)

[82]

[82] - A Tapestry: Rest after the Harvest (17th century)

[83]

[83] - A Chest of Drawers (18th century)

[84]

[84] - A Painting: The Virgin and Saint Antoine of Padua (18th century)

[85]

[85] - A Painting: The Dead Christ (18th century)

[86]

[86] - A Painting: The Descent from the Cross (18th century)

[87]

[87] - A Painting: Virgin and child (17th century)

[88]

[88] - A Commemorative Plaque (1654)

[89]

[89] - A Bronze Bowl (16th century)

[90]

[90]

- A Tapestry: Pagan Sacrifice to an Idol (18th century)

- The Church of Saint-Jacques de Lhoumeau (1840)

[91] The church contains a Gallery Organ (18th century)

[91] The church contains a Gallery Organ (18th century) which is registered as an historical object.[92][93][94]

which is registered as an historical object.[92][93][94] - The Church of Saint-Martial (1849)

[95] in Neo-Romanesque style by Paul Abadie. The church contains a large number of items that are registered as historical objects. For a complete list with links to descriptions (in French) click here.

[95] in Neo-Romanesque style by Paul Abadie. The church contains a large number of items that are registered as historical objects. For a complete list with links to descriptions (in French) click here. - The Church of Saint Ausone from the same period and architect. The church contains a Statue of Saint Ausone (17th century)

which is registered as an historical object.[96]

which is registered as an historical object.[96] - The Chapel Notre-Dame d'Obézine (or Bézines)(1895)

[97]

[97] - The Hôtel-Dieu

- The old Carmelite convent

- Picture Gallery

-

An Aureola on the Cathedral

-

Church of Obézine

-

Chapel Saint-Roch

-

Church of the Sacred Heart

-

Church of Saint-Jacques de l'Houmeau

-

Church Saint-Ausone

-

Chapel Saint-Cybard

-

Chapel of Cordeliers

-

"Lantern of the dead" near the Church of Saint-André

Environmental heritage

The valley of the Charente upstream from Angoulême is a Natura 2000 zone with remarkable species: 64 species of birds.[98] Among them are species for marshland and wetland; and at Angoulême it is common to see diving and swimming birds, swans (mute swan), grebes (black-necked grebe, little grebe, horned grebe, great crested grebe), geese (greylag goose), ducks (gadwall, pintail, wigeon, shoveler), teal (garganey, teal) and scaup (pochard, tufted duck) on the Charente. It is more rare to see waders. Terns, gulls (laughing gull), great cormorants, return during periods of storms from far upstream on the river.

Marquet island and the Forest of la Pudrerie have been finally cleared and will be provided to the population.

Hiking trails and an old haulage road have become part of the green corridor which allows walks along the river.

Museums

- Museum of Angoulême

- Museum of Paper

[99]

[99] - Museum of the Archaeological and Historical Society of Charente

- Museum of Resistance and Deportation

- Museum of Cartoons (CIBDI)

- Decentralized branch of the Regional Contemporary Art Fund of Poitou-Charentes

Cartoons

In 1983 the Regional School of Fine Arts in Angoulême (EESI) was created with the first cartoon section in France. Angoulême is home to the International City of Cartoons and Images which registers all the comics published in France. There is also at la Cité the ENJMIN which is the first state-funded school in Europe for the key subjects of video games and interactive media.

- Angoulême, known as the "City of the Image" or "Capital of Cartoons", is known for its "Painted walls" of cartoons "that punctuate the city centre.[100]

Other cultural places

- The National Theatre[101]

- The Espace Carat' (Exhibition and Convention Centre of Grand Angoulême - events, concerts)[102]

- La Nef (Concert Hall)[103]

- Gabriel Faure conservatory which has an auditorium and a library[104]

- The Alpha, a library currently under construction (opening scheduled for March 2014)

Schedule of festivals

End of January: Angoulême International Comics Festival Late May: Musiques Métisses (Mixed Music) Late August: Festival of Francophone Films September: Circuit des Remparts (Car Race) Late October: Piano en Valois Late November: Gastronomades Early November: The Grand Dance Festival

City of festivals

Angoulême, along with paper and printing, has long been associated with animation, illustration and the graphic arts. The Cité internationale de la Bande Dessinée et de l'Image[105] includes an exhibition space and cinema in a converted brewery down by the river. A new museum dedicated to the motion picture opened in 2007 at the newly restored chais on opposite side of the river at Saint Cybard. The architect was Jean-François Bodin. The Angoulême International Comics Festival takes place for a week every year in January and attracts nearly a quarter of a million international visitors.

Another festival, small yet influential, is FITA, held each December. FITA stands for Forum International des Technologies de l’Animation, International Forum for Animation Technologies. The event was started in 1998. Some 250 – 300 French professionals from animation, effects, post-production and game development studios: SFX supervisors, head of studios, animators, technical directors, meet to share information and hear internationally renowned speakers on the latest advances and new ideas in entertainment technology.

The Circuit des Remparts motor racing event, with its street circuit around the ramparts and past the Cathedral, is held the Sunday of the middle weekend in September. It is also the occasion of the world's largest gathering of pre-war Bugatti race cars, usually around 30 cars, many being examples of the legendary T35, the Ferraris of their day. British vintage and classic cars are also in attendance, most having been driven to the event. The Saturday of the "Remparts" weekend includes a tourist rally (as opposed to a speed event) for classic and sporting cars, around the Cognac area.

In another international sports event, Angoulême was the site of the finish of Stages 18 and 19 (ITT) in the 2007 Tour de France.

Angoulême also hosts the Gastronomades festival at Christmas, Music Metisse in May and Piano en Valois in October.

A new exhibition centre (Le Parc Des Expos) and a new shopping mall at the Champ de Mars in the town centre (opening Sept/Oct 2007) are the latest additions to the town.

Angoulême is the seat of a bishop, a prefect, and an assize court. Its public institutions include tribunals of first instance and of commerce, a council of trade-arbitrators, a chamber of commerce and a branch of the Bank of France. It has several lycées (including the Lycee de l'Image et du Son d'Angoulême (LISA – High School of Image and Sound)), training colleges, a school of artillery, a library and several learned societies.

Facilities and services

Education

Colleges

- Marguerite de Valois College

- Anatole France College

- Pierre Bodet College

- Jules Michelet College

- Jules Verne College

- Michèle Pallet College

Schools

- Lycée Guez-de-Balzac : general education school hosting literary CPGEs

- School of Image and Sound of Angoulême (LISA): a general education high school (options cinema, theatre), BTS audiovisual and visual communication

- Marguerite de Valois High School : general and technological lycée,

- Charles de Coulomb High School: a general and technological education and vocational high school (industrial education)

- Sillac High School: building trades vocational school

- Jean Rostand School: vocational school for the fashion industry and services,

- Jean-Albert Grégoire School: vocational school for careers in transport and logistics (Soyaux commune)

- Oisellerie High School: agricultural college (La Couronne commune)

- Saint Paul High School: A private school grouping (school, college, and general and technological school)

- Sainte-Marthe-Chavagnes School: a private school grouping (from kindergarten to BTS, general education, technological and professional)

University

The University Centre of Charente is administratively attached to the University of Poitiers. It includes:

- a Faculty of Law and Social Sciences

- a Faculty of Sport Sciences

- CEPE (European Centre for children's products)

- University Institutes of Technology (IUT)

- a departmental site of the Graduate School of Teaching and Education from the University of Poitiers

Other institutions

- Gabriel Fauré Conservatory directed by Jacques Pesi. 56 teachers, 40 disciplines, and 1,015 students in 2010[106]

- Isfac: a training centre offering 8 BTS courses alternately as well as training for business

- CNAM: a branch of the National Conservatory of Arts and Crafts

- EMCA: School for film animation

- EGC: School of Management and Business

- CIFOP: Vocational Training Centre for the Chamber of Commerce and Industry of Angoulême (L'Isle-d'Espagnac commune)

- EIA: Engineering school by apprenticeship - CESI

- ENJMIN: National School game and interactive digital media

- EESI: Higher European School of Imaging

- CREADOC: documentary of design

Sports

- Sailing school, based by Éric Tabarly at the lake of Saint-Yrieix

- The women's handball team was in division 1 for the 2008-2009 season.

- The Angoulême CFC (ACFC) is the football club who played in the National (3rd division) in the 2003-2004 season.

- TTGF is the Table Tennis Club who played in National 1 (3rd division championship of France) for the 2009-2010 season.

- The SC Angoulême Rugby Club

- The ACA (Angoulême Rowing Club)

Health

All medical and paramedical specialties are present.

- The Centre hospitalier d'Angoulême, also called the Hospital of Girac, is in the commune of Saint-Michel.[107]

- The Saint-Joseph clinic is the only remaining clinic in the commune of Angoulême. Other clinics (Victor Hugo, Sainte-Marie, Saint-Cybard, etc.) are combined on one site: the clinical centre of Soyaux.

Local life

Worship

Catholic worship

- Saint-Pierre Cathedral

- Saint-André Church

- Church of Our Lady of Obézine

- Church of St. Ausone

- Saint-Jacques Church of l'Houmeau

- Church Saint-Martial

- Church of Saint-Bernadette

- Parish church of Saint-John the Baptist: the church is located on the Rue Pierre Aumaître

- Church of Saint-Cybard

- Church of the Sacred Heart

Markets

- The market of Halles, or Covered Market. With its large roof and its late 19th-century architecture, it has been registered as an historical monument since 1993.[108]

- The Victor Hugo market

- The market of Saint-Cybard

- The districts of Basseau and Ma Campagne also have their markets.

Military presence

Two regiments of the French armed forces are currently garrisoned in the City:

1st Marine Infantry Regiment

- The 515th régiment du train.

Several other military formations have been previously garrisoned in the city, including:

.jpg) The 107th Infantry Regiment, from before 1906 for an unknown period of time and then from in 1939 to 1940

The 107th Infantry Regiment, from before 1906 for an unknown period of time and then from in 1939 to 1940- The 21st Artillery Regiment, 1906

- The 34th Artillery Regiment, 1906

- The 41st Divisional Artillery Regiment, 1939–1940

- The 502nd Tank Regiment, 1939–1940.

Notable people linked to the commune

- Born in Angoulême

- Isabelle Taillefer (1186-1246), known as Isabelle of Angoulême. The last descendant of the line of the counts Taillefer of Angoulême, she became Queen of England in 1200 through her marriage to King John of England.

- Jean d'Orléans (1400-1467), the "good Count Jean of Angoulême". Grandson of King Charles V of France, son of Duke Louis of Orléans and of Valentina Visconti, brother of the famous poet Charles d'Orléans and grandfather of King François I. Count Jean left memories of a wise man, educated and very religious. After 32 years of captivity in England, he settled in his county in Angoulême then at Cognac. At the end of the Hundred Years War he began works of reconstruction on his land. His popularity was immense hence the adjective "good count". He has been buried in Saint-Pierre d'Angoulême Cathedral for 540 years.

- Mellin de Saint-Gelais, born about 1491 in Angoulême and died in October 1558, he was a French poet of the Renaissance who was favoured by François I.

- Marguerite d'Angoulême, the eldest sister of François I, born in Angoulême and known locally under the name of "Marguerite de Valois" by birth or "Marguerite de Navarre" by her marriage.

- Hélie du Tillet, Mayor of Angoulême in 1502, father of the historian Jean du Tillet.

- André Thévet (1516-1592): explorer and writer, reported from Brazil: "angoumoisine grass" or tobacco, later introduced at the court of France by Jean Nicot.

- François Ravaillac (1578-1610): notorious for having murdered King Henry IV.

- François Garasse (1585-1631), author of The Doctrice curious wits of that time - or alleged so.

- Jean-Louis Guez de Balzac (1597-1654): writer.

- Jean Nestor de Chancel, General, guillotined during the Terror.

- Marc-René de Montalembert (1714-1800): military man and diplomat, creator of the Foundry of Ruelle in 1753.

- Jean-Baptiste Vallin de la Mothe (1728-1799): one of the favourite architects of the Empress Catherine II of Russia, Saint- Catherine's Church, the Little Hermitage (now the Hermitage Museum) and the Imperial Academy of Arts of Saint Petersburg are among his masterpieces.

- André Guillaume Resnier de Goué (1729-1811): French general and one of the pioneers of aviation and gliding.

- Charles de Coulomb (1736-1806), French physicist, gave his name to the unit of electric charge.

- Cybard Florimond Gouguet (1752-1831), general of the armies of the Republic and the Empire.

- Jean Chemineau (1771-1852), born at Grelet, general of the armies of the Republic and the Empire.

- Besson Bey J.V. (real name J.V. Besson) (1782-1837) was, among others, an Admiral for Muhammad Ali, viceroy of Egypt.

- Octave Callandreau (1852-1904), French astronomer, native of Angoulême.

- Paul Iribe (1883-1935): designer and decorator French. He is considered one of the forerunners of "Art Deco".

- Robert Couturier, (1905-2008), sculptor.

- Paul Cognasse, (1914-1993), painter, glazier, and sculptor.

- Jacques Mitterrand, General of the Air Force and company director, born in Angoulême in 1918.

- René Chabasse, born 9 April 1921, killed on 21 February 1944 in Angoulême by a German soldier, a French resistance fighter.

- Dominique Bagouet, (1951-1992), French dancer and choreographer of contemporary dance.

- Maurice Duverger, lawyer, political scientist and professor of French law, constitutional law scholar.

- Bruno Maïorana, designer of comics, born in Angoulême on 23 December 1966

- Claude Arpi, born in 1949, writer, journalist, historian and French tibetologist.

- Claire Désert, born in 1967, pianist, professor at the Paris Conservatory (CNSM).

- Amandine Bourgeois, born in 1979, singer

- Laurence Arné, born in 1982, comedian